полная версия

полная версияПолная версия

The Lyon in Mourning, Vol. 1

When Donald and Malcolm were talking of the barbarous usage they themselves and others met with, they used to say, 'God forgie them; but God lat them never die till we have them in the same condition they had us, and we are sure we would not treat them as they treated us. We would show them the difference between a good and a bad cause.'

Donald MacLeod spoke very much good of Mr. James Falconar, a Scots non-jurant clergyman, and Charles Allan, son of Hary Allan in Leith. He said that Charles Allan behaved exceedingly well in his distress, and had very much of [fol. 315.] the gentleman about him, and that he was in a state of sickness for some time. He said that Mr. Falconar was scarce ever any way ill in his health, that he bore up better than any one of them, having a great fund of spirits, being always chearful, and never wanting something to say to divert them in their state of darkness and misery. He added that he did not know a better man, or one of greater courage and resolution in distress.

Donald desired me to take notice that he was set at liberty (out of a messenger's house in London, where he had been but a short time) upon a most happy day, the 10th of June 1747.145

June

Donald has got in a present a large silver snuff-box prettily chessed, from his good friend, Mr. John Walkingshaw of London, which serves as an excellent medal of his history, as it has engraven upon it the interesting adventure, with proper mottos, etc. The box is an octagon oval of three inches and three quarters in length, three inches in breadth, and an inch and a quarter in depth, and the inside of it is doubly gilt. Upon the lid is raised the eight-oar'd boat, with Donald at the helm, and the four under his care, together with the eight rowers distinctly represented. The sea is made to appear very [fol. 316.] rough and tempestuous. Upon one of the extremities of the lid there is a landskip of the Long Isle, and the boat is just steering into Rushness, the point of Benbicula where they landed. Upon the other extremity of the lid there is a landskip of the end of the Isle of Sky, as it appears opposite to the Long Isle. Upon this representation of Sky are marked these two places, viz., Dunvegan and Gualtergill. Above the boat the clouds are represented heavy and lowring, and the rain is falling from them. The motto above the clouds, i. e. round the edge of the lid by the hinge, is this – Olim hæc meminisse juvabit – Aprilis 26to 1746. The inscription under the sea, i. e. round the edge of the lid by the opening, is this – Quid, Neptune, paras? Fatis agitamur iniquis. Upon the bottom of the box are carved the following words – Donald MacLeod of Gualtergill, in the Isle of Sky, the faithfull Palinurus, Æt.68, 1746. Below these words there is very prettily engraved a dove, with an olive branch in her bill.

When Donald came first to see me, along with Deacon Clark, I asked him why he had not snuff in the pretty box? 'Sneeshin in that box!' said Donald. 'Na, the deel a pickle sneeshin shall ever go into it till the K – be restored, and then (I trust in God) I'll go to London, and then will I put [fol. 317.] sneeshin in the box and go to the Prince, and say, "Sir, will you tak a sneeshin out o' my box?"'

20 Aug.

N.B.– Donald MacLeod, in giving his Journal, chused rather to express himself in Erse than in Scots (as indeed he does not much like at any time to speak in Scots), and Malcolm MacLeod and James MacDonald explained to me. I was always sure to read over every sentence, in order to know of them all if I was exactly right. Malcolm MacLeod and James MacDonald were exceedingly useful to me in prompting Donald, particularly the former, who having heard Donald tell his story so often before in company, put him in mind of several incidents that he was like to pass over. Donald desired Malcolm to refresh his memory where he thought he stood in need, for that it was not possible for him to mind every thing exactly in such a long tract of time, considering how many different shapes and dangers they had gone through in that time.

August 20th. When I was writing Donald's journal from his own mouth, I did not part with him till betwixt 10 and 11 o'clock at night, and before we parted, our company increased to 16 or 17 in number.

7 Sept.

Some days after this Donald MacLeod and James MacDonald [fol. 318.] coming to dine with my Lady Bruce, I made an appointment with Donald to meet James MacDonald and me upon Monday, September 7th, with a view to dine with Mr. David Anderson, senior, in the Links of Leith, who was very desirous to see Donald, and to converse with him for some time. Upon the day appointed Donald came down from Edinburgh, and brought along with him Ned Bourk, to shew him Mr. Anderson's house. When Ned was known to be the person that was along with Donald, he was desired to come into the house and get his dinner. I went out from the company a little to converse with Ned, who put into my hand a paper, telling me that this was his account of the matter. When I returned to the company, I told them what I had got from Ned, and they were all desirous to know the contents of it. After dinner, when I was reading Ned's Journal, Donald MacLeod frowned, and was not pleased with his account of things, and therefore would needs have Ned brought into the room to answer for himself. Accordingly Ned was called in, and after a pretty long and warm debate betwixt them in Erse, we found that Donald's finding fault amounted to no more than that Ned had omitted to mention several things, which Ned acknowledged to be the case, confessing that his memory did not serve him as to many particulars.

9 Sept.

The Journal had been taken from Ned's own mouth in a [fol. 319.] very confused, unconnected way, as indeed it requires no small attention and pains to come at Ned's146 meaning in what he narrates, because he speaks the Scots exceedingly ill. I therefore desired Ned to be with me in my own room upon Wednesday's afternoon, September 9th, that I might have the opportunity of going through his Journal with him at leisure, and likewise of having an account from his own mouth how he happen'd to be so lucky as to escape being made a prisoner, when so many were catched upon the Long Isle, where he skulked for some time. Ned kept his appointment, as will hereafter appear.

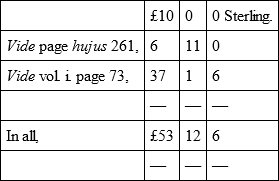

Though Donald MacLeod's history be most extraordinary in all the several instances of it (especially considering his advanced age), yet when he arrived at Leith, he had not wherewith to bear his charges to Sky, where he has a wife and children, from whom he had been absent for at least one year and an half. There was therefore a contribution set on foot for him in and about Edinburgh; and I own I had a great anxiety for my own share to make out for honest Palinurus (if possible) a pound sterling for every week he had served the Prince in distress; and (I thank God) I was so happy as to [fol. 320.] accomplish my design exactly. Donald MacLeod and James MacDonald came from the Links of Leith to my room, as they were to sup that night with my Lady Bruce upon invitation. I then delivered into Donald's own hand, in lieu of wages for his services of ten weeks,

The above sum went through my hands in the compass of about thirteen months and an half. Meantime I have not reckoned up a guinea, half a guinea, or a crown, which I had from time to time from my Lady Bruce, as a necessitous sufferer happened to come in the way.

God Almighty bless and reward all those who liberally contributed for the support of the indigent and the deserving in times of the greatest necessity and danger, for Jesus Christ's sake. Amen and Amen.

20 Aug.

At the same time above mentioned, I gave Donald MacLeod the trouble of two letters, copies whereof follow.

Copy of a Letter to Mr. Alexander MacDonald of Kingsburgh in Sky

7 Sept.

Dear Sir, – I could not think of honest Palinurus's setting out upon his return to Sky, without giving you the trouble of some few lines, to wish you and Mrs. MacDonald much joy [fol. 321.] and happiness in being at your own fireside again. You and all your concerns are frequently made mention of here with very much respect; and so long as a spark of honesty remains, the name of MacDonald of Kingsburgh will ever have a mark of veneration put upon it.

You know very well how I employ much of my time in a certain affair. I have already made up a collection of between twenty-four and thirty sheets of paper, and I would fain flatter myself with the hopes of still increasing the number till the collection be made compleat, by your assistance and that of other worthies who prefer truth to falshoods, and honesty to trick and deceit. Now is the time or never to make a discovery of facts and men; and it is pity to omit any expedient that may tend to accomplish the good design.

I gave Captain Malcolm MacLeod the trouble of a written Memorandum, which I hope you will honour with a plain and distinct return; and hereby I assure you no other use shall be made of it but to preserve it for posterity; it being my intention not so much as to speak of it, and to make a wise and discreet use of every discovery I am favoured with.

[fol. 322.] I wish the worthy Armadale would be so good as to give his part of the management from his own mouth. But as I have writ fully by the same hand to the faithful Captain Malcolm MacLeod upon this and some other particulars, to his letter I refer you, and I hope you will join your endeavours with him in serving the cause of truth and justice.

For my own part I am resolved to leave no stone unturn'd to expiscate facts and characters, that so the honest man may be known and revered, and those of the opposite stamp may have their due.

That God Almighty may ever have you, Mrs. MacDonald, and all your concerns in His holy care and protection, is the hearty and earnest prayer of, my dear Sir, your most affectionate friend and very humble servant,

Robert Forbes.Citadel of Leith, September 7th, 1747.

P.S.– Palinurus has promised to drop me a line by post to inform me of his safe arrival, and about your welfare, and that of other friends. Pray keep him in mind of his promise, and let him not mention any other thing in his letter. Is it possible to get Boisdale's part from himself? I would gladly have it. You see I am exceedingly greedy. Adieu.147

Copy of a Letter to Captain Malcolm MacLeod of Castle in Raaza

[fol. 323.] Dear Sir, – This comes by honest Palinurus to congratulate you upon your safe return to your own place; I wish I could say to your own fireside. But I hope that and all other losses will be made up to you with interest in due time. A mind free from the sting of bitter reflections is a continual feast, and will serve to inspire a man with spirits in a low and suffering state of life, made easy by contentment, whilst others are miserable under a load of riches and power, and must betake themselves to a crowd of company to keep them from thinking.

I hope you are happy in meeting with Mrs. MacLeod in good health. Long may ye live together, and may your happiness increase.

I need not put you in mind of my Memorandum to Kingsburgh, and of your promise to procure me an exact account from the mouth of your brother-in-law, Mr. MacKinnon, as to his particular concern in the adventure, for you have too much honour to neglect anything committed to your trust.

I heartily wish that honest Armadale could be prevailed upon to give a full and plain account of his part of the management [fol. 324.] in a certain affair which is very much wanted. If he intends to visit Miss Flora while in Edinburgh, I then can have the happiness of conversing with that truly valuable man, and of getting his history from his own mouth. But if he comes not to this country soon, I earnestly beg you'll employ your good offices with him to allow you to write it down in his own words. Though I have not the honour of that worthy gentleman's acquaintance, please make him an offer of my best wishes to him and his family in the kindest manner, and tell him that he has a most amiable character amongst the honest folks in and about this place. May God Almighty multiply his blessings upon him, and all his concerns both here and hereafter.

If I rightly remember I desired the favour of you to lay yourself out in procuring me an exact account of all the cruelties and barbarities, the pillagings and burnings, you can get any right intelligence about, which will be an infinite service done to truth. In doing of this be so good as to be very careful in finding out the names of persons and places as much as possible. But where the names cannot be discovered, still let the facts themselves be particularly set down.

Though I have not the honour of being known to the worthy [fol. 325.] family of Raaza, I beg my most respectful compliments may be presented to them.

I need not mention to you that regard which is entertained for you by the worthy person, the protection of whose roof I enjoy; for I dare say you cannot fail to be sensible with what respect you and all such are made mention of here.

That God Almighty may bless you and Mrs. MacLeod with health and happiness and give you your hearts desire is the hearty and earnest prayer of, my dear Sir, Your most affectionate friend and very humble servant,

Robert Forbes.Citadel of Leith, September 7th, 1747.

P.S.– By the same hand I have sent a letter to that valuable and faithful gentleman, Kingsburgh, with whom you may compare notes.148

7 Sept.

September 7th.– Donald MacLeod when at supper spoke much in commendation of Ned Burk as being an honest, faithful, trusty fellow.149 He said in the event of a R[evoluti]on Ned would carry a chair no more; for he was persuaded the Prince would settle an hundred pounds sterling a year upon Ned during life. And he could affirm it for a truth that not any man whatsomever deserved it better. Meantime Donald added that Ned, though true as steel, was the rough man, and that he used great freedoms; for he had seen him frequently [fol. 326.] at Deel speed the leers with the Prince, who humour'd the joke so well that they would have flitten together like twa kail wives, which made the company to laugh and be merry when otherwise they would have been very dull.

Robert Forbes, A.M.Wednesdays afternoon, September 9th, 1747.9 Sept.

At the hour appointed (4 o'clock) Ned Bourk came to my room, when I went through his Journal with him at great leisure, and from his own mouth made those passages plain and intelligible that were written in confused, indistinct terms.

A Short but Genuine Account of Prince Charlie's Wanderings from Culloden to his meeting with Miss MacDonald, by Edward Bourk.1501746 16 Apr.

Upon the 16th of April 1746 we marched from the field of Culloden to attack the enemy in their camp at Nairn, but orders were given by a false151 general to retreat to the place from whence we had come, and to take billets in the several parts where we had quartered formerly. The men being all much fatigued, some of them were dispersed here and there in order to get some refreshment for themselves, whilst the greater part of them went to rest. But soon after, the enemy appearing behind us, about four thousand of our men were with difficulty got together and advanced, and the rest were awakened by the [fol. 327.] noise of the canon, which surely put them in confusion. After engaging briskly there came up between six and seven hundred Frazers commanded by Colonel Charles Frazer, younger, of Inverallachie, who were attacked before they could form in line of battle, and had the misfortune of having their Colonel wounded, who next day was murdered in cold blood, the fate of many others.

Our small, hungry, and fatigued army being put into confusion and overpowered by numbers, was forced to retreat. Then it was that Edward Bourk fell in with the Prince, having no right guide and very few along with him. The enemy kept such a close fire that the Prince had his horse shot under him;152 who, calling for another, was immediately served with one by a groom or footman, who that moment was killed by a canon bullet. In the hurry, the Prince's bonnet happening to fall off, he was served with a hat by one of the life-guards. Edward Bourk, being well acquainted with all them bounds, undertook to be the Prince's guide and brought him off with Lord Elcho, Sir Thomas Sheridan, Mr. Alexander MacLeod, aid-de-camp, and Peter MacDermit, one of the Prince's footmen. Afterwards they met with O'Sullivan, when they were but in very bad circumstances. The Prince was pleased to say to Ned, if you be a true friend, pray endeavour to lead us safe off. Which honour Ned was not a little fond of, and promised [fol. 328.] to do his best. Then the Prince rode off from the way of the enemy to the Water of Nairn, where, after advising, he dismist all the men that were with him, being about sixty of Fitz-James's horse that had followed him. After which Edward Bourk said, 'Sir, if you please, follow me. I'll do my endeavour to make you safe.' The Prince accordingly followed him, and with Lord Elcho, Sir Thomas Sheridan, O'Sullivan, and Mr. Alexander MacLeod, aid-de-camp, marched to Tordarroch, where they got no access, and from Tordarroch through Aberarder, where likewise they got no access; from Aberarder to Faroline, and from Faroline to Gortuleg, where they met with Lord Lovat, and drank three glasses of wine with him.

April

About 2 o'clock next morning with great hardships we arrived at the Castle of Glengary, called Invergary, where the guide (Ned Burk) spying a fishing-net set, pulled it to him and found two salmonds, which the guide made ready in the best manner he could, and the meat was reckoned very savoury and acceptable. After taking some refreshment the Prince wanted to be quit of the cloathing he had on, and Ned gave him his own coat. At 3 o'clock afternoon, the Prince, O'Sullivan, another private gentleman, and the guide set out and came to the house of one Cameron of Glenpean, and stayed there all night. In this road we had got ourselves all nastied, and when [fol. 329.] we were come to our quarters, the guide happening to be untying the Prince's spatter dashes, there fell out seven guineas. They being alone together, the Prince said to the guide, 'Thou art a trusty friend and shall continue to be my servant.'

From Glenpean we marched to Mewboll, where we stayed one night, and were well entertained. Next morning we went to Glenbiasdale, stayed there four nights or thereabouts, and from that we took boat for the Island of South Uist, about six nights before the 1st of May, where we arrived safely but with great difficulty. There we stayed three days or so, and then we boated for the Island Scalpa, or Glass, and arrived at Donald Campbell's house.

When I asked at Ned to whom Scalpay belonged, he answered, To the Laird of MacLeod. I asked likewise, what this Donald Campbell was? Ned told me that he was only a tenant, but one of the best, honestest fellows that ever drew breath; and that his forefathers (from father to son) had been in Scalpa for several generations past. Ned said he believed they were of the Campbells of Lochniel.

May

In Scalpa we stayed about three days, sending from thence our barge to Stornway to hire a vessel. By a letter from Donald MacLeod we came to Loch Seaforth, and coming there by a false guide, we travelled seven hours, if not more, under cloud of night, having gone six or eight miles out of our way. This guide was sent to Stornway to know if the vessel was [fol. 330.] hired. Either by him or some other enemy it was divulged that the Prince was at Kildun's house (MacKenzie) in Arynish, upon which a drum beat in Stornway, and upwards of an hundred men conveened to apprehend us. However the MacKenzies proved very favourable and easy, for they could have taken us if they had pleased. We were then only four in number besides the Prince, and we had four hired men for rowing the barge. Upon the alarm Ned Burk advised they should take to the mountains; but the Prince said, 'How long is it, Ned, since you turned cowardly? I shall be sure of the best of them ere taken, which I hope shall never be in life.' That night he stood opposite to the men that were gathered together, when two of our boatmen ran away and left us. The rogue that made the discovery was one MacAulay, skipper of the vessel that was hired, who next morning went off to Duke William with information. In the morning we had killed a quey of little value, and about 12 o'clock at night our little barge appeared to us, whereof we were very glad. We put some pieces of the quey in the barge and then went on board. We rowed stoutly; but spying four men of war at the point of the Isle of Keaback we steered to a little desart island where were some fishermen who had little huts of houses like swine's [fol. 331.] huts where it seems they stayed and made ready their meat while at the fishing. They were frighted at seeing our barge sailing towards the island, and apprehending we had been a press boat from the men-of-war they fled and left all their fish.

When landed Edward Burk began to dress some of the fish, but said he had no butter. The Prince said, 'We will take the fish till the butter come.' Ned, minding there was some butter in the barges laid up among bread, went to the barge and brought it; but it did not look so very clean, the bread being all broke in pieces amongst the butter; and therefore Ned said he thought shame to present it. The Prince asked if the butter was clean when put amongst the bread. Ned answered it was. 'Then,' said the Prince, 'it will do very well. The bread is no poison; it can never file the butter.'

April.

Ned having forgot here to mention the cake which the Prince contrived with the cow's brains I asked him about it; and he acknowledged the truth of it. I likewise asked him if he knew the name of the desart island; but he frankly owned that he did not know it, assuring me in the mean time that Donald MacLeod knew it well.153

Upon the desart island we stayed four nights, and on the [fol. 332.] 5th set to sea and arrived at the Island Glass, where we were to enquire about the hire of Donald Campbell's boat. Here four men appeared coming towards them, upon which Ned Burk went out of the boat to view them, and giving a whistle, cried back to his neighbours, being at some distance, to take good care of the boat. Ned not liking these men at all, thought fit to return with speed to the boat, and putting his hand to the gunnel jumped aboard and stayed not to converse with the four men.

May.

From Glass, having no wind, we rowed off with vigour. About break of day, the wind rising, we hoisted sail; and all of us being faint for lake of food, and having some meal, we began to make drammach (in Erse, stappack) with salt water, whereof the Prince took a share, calling it no bad food, and all the rest followed his example. The Prince called for a bottle of spirits, and gave every one of us a dram. Then we passed by Finsbay, in the Isle of Harris, where we spied a man-of-war, commanded by one Captain Ferguson, under full sail, and our little sail was full too. He pursued us for three leagues; but we escaped by plying our oars heartily, they being better to us than arms could have been at that time. The water failing the man-of-war, he was not in a condition [fol. 333.] to pursue farther. We steered upon a point called Rondill, when the Prince expressed himself as formerly that he should never be taken in life. After this the said Captain Ferguson, being anxious to know what we were, endeavoured to make up with us a second time, but to no purpose, the water being at ebb, and we continuing still to row in amongst the creeks. Seeing this he turned to the main sea, when we sailed to Lochmaddy to the south of the Isle of Uist, thence to Loch-uiskibay, thence to an island in said loch, where we came to a poor grasskeeper's bothy or hut, which had so laigh a door that we digged below the door and put heather below the Prince's knees, he being tall, to let him go the easier into the poor hut. We stayed there about three nights, and provided ourselves very well in victuals by fowling and fishing, and drest them in the best shapes we could, and thought them very savoury meat. Thence we went to the mountain of Coradale, in South Uist, and stayed there about three weeks, where the Prince one day, seeing a deer, run straight towards him, and firing offhand killed him. Edward Burk brought home the deer, and making ready some collops, there comes a poor boy, [fol. 334.] who, without asking questions, put his hand among the meat, which the cook (Edward Burk) seeing, gave him a whip with the back of his hand. The Prince observing this, said, 'O man, you don't remember the Scripture which commands to feed the hungry and cleed the naked, etc. You ought rather to give him meat than a strip.' The Prince then ordered some rags of cloaths for the boy, and said he would pay for them, which was done accordingly. The Prince added more, saying, 'I cannot see a Christian perish for want of food and raiment had I the power to support them.' Then he prayed that God might support the poor and needy, etc.