полная версия

полная версияOur Benevolent Feudalism

The Contract-labor law is another measure, to the seigniorial mind, unnecessary and obstructive, and its provisions, therefore, are but lightly observed. Known evasions have been numerous; and, were the full truth revealed, it would probably be found that this law has met with about the same degree of observance as have the Interstate Commerce and Anti-trust laws. As recently as July 16th, comes word from Berlin to the Chicago Daily News that “agents of American railroads are canvassing the Polish and Slavic districts of Europe for laborers, to whom they offer $2.50 a day and board, regardless of the Federal Contract-labor law.”

Not only do the magnates demand immunity from government interference in their business affairs, but they demand also a more real, if not a more obvious, share in the operations of government. The invasion, during the last ten years, of the National Senate by a number of the magnates or their legates is a part of the process; but something more to the point is their insistence on the right to be consulted in grave affairs by the President and Cabinet. A New York daily newspaper, edited by the distinguished scholar who delivers lectures on journalism before Yale University, published last February an account of a remarkable gathering at Washington. It verges closely upon contumacy to mention the names of the attending magnates, such is their eminence, and they will therefore not be given. Their purpose was to protest to the President against a repetition of his action in the Northern Securities case. “The financiers declare,” says this newspaper, “that they should have been notified of the intended Federal action last week, so that they could be prepared to support the stock market, and that their unpreparedness came very near bringing on a panic. Had not the big interests of the street been in possession of the bulk of securities, instead of speculators and small holders, there would have been a panic, the capitalists assert.” It is, when considered, a modest claim – the powers of an extra-constitutional cabinet, intrusted with the conservation of the public peace. There is no proof that the claim has been conceded, though some light is thrown on the problem by the newspaper’s further declaration that the chief magnate, after an interview with the President, “felt very much better.”

Something of the same nature was revealed in the negotiations last March between the Mayor of New York City and the directors of the New York Central Railroad Company. The company requested the Mayor to secure the withdrawal of the Wainwright bill in the State Assembly, compelling the railroad to abandon steam in the Park Avenue tunnel by a fixed date, and promised to do the required thing in its own time and at its own pleasure. The letter of the Mayor to Assemblyman Bedell records the result: “This letter [of the directors] seems to me to lay a good foundation for the waiving a fixed date to be named in the bill;” and the date was accordingly “waived.”

Of the seigniorial attitude toward the police law, the abundant crop of automobile cases alone furnishes signal testimony. Dickens made a highly dramatic, though perhaps rather unhistorical, use in his “A Tale of Two Cities” of the riding down of a child by a marquis, and the long train of tragic consequences that ensued. We do the thing differently in our day: we acquit, or at most fine the marquis, and the matter rests; we are too deferential to carry it further. Fast driving in the new “machines” has become one of the tests of courage, manliness, and skill, – what jousting in full armor was in the fifteenth century, or duelling with pistols in the early part of the nineteenth, – and if the police law interferes, the exploit is the more hazardous and therefore the more emulatory. The scion of a great house who recently, on being arrested for fast driving and then bailed, subsequently sent his valet to the police court to pay the fine, showed the true seigniorial spirit. Possibly, though, had his identity been known before arrest, he would have escaped the irritating interference of the law; for it happened, about the same time, on the arrest for the same offence of a millionnaire attorney, companioned by a Supreme Court judge, that a too vigilant policeman came to learn his severest lesson – that to know whom not to trouble is the better part of valor.

At Newport, the summer home of the seigniorial class, the automobile enforces a right of way. This is not sufficient, however, for the automobilists, who would prefer a sole and exclusive way. In the summer of 1901 the resident magnates fixed upon a certain Friday afternoon for their motor races, and demanded exclusive control of Ocean, Harrison, and Carroll avenues between the hours of two and four o’clock. In the “grand style” characterizing the dealings of this class with the public, the magnates offered to pay all the fines if the races led to any prosecutions. This meant, of course, that the ordinance prohibiting a speed greater than ten miles an hour was to be overlooked, since the races would surely have developed speed up to forty, fifty, and sixty miles an hour. The deferential City Council acquiesced. For once, however, the ever serviceable injunction was found to be available against other persons than striking workmen. A few property owners sought refuge in the Supreme Court, a temporary injunction was issued by Judge Wilbur, and, though the magnates hired lawyers to fight it, the order was made permanent. It is but natural that keen resentment should follow this high-handed action of the courts. It is announced that some of the magnates are tiring of Newport, and one of the wealthiest of them has recently threatened to forsake the place entirely.

Laws are like cobwebs, said Anacharsis the Scythian, where the small flies are caught and the great break through. Yet that even the great can sometimes bow to the reign of law, and particularly that the seigniorial mind can on occasion be conciliatory, is well illustrated by the recent action of the governors of the Automobile Club, in suspending two members and disciplining a third, for fast driving. The troublesome restrictions of the law on this point are probably destined, however, to be soon abolished. Already the Board of Freeholders of Essex County, N.J., a region much frequented by automobilists, has advanced the speed limit in the country districts to twenty miles per hour. Further changes are expected, and it will probably be but a short time before a man with a “machine” will enjoy the God-given right of “doing what he will with his own.”

III

Most of the magnates show a frugal and a discriminating mind in their benefactions; but it is a prodigal mind indeed which governs the expenditures that make for social ostentation. It is probable that no aristocracy – not even that of profligate Rome under the later Cæsars – ever spent such enormous sums in display. Our aristocracy, avoiding the English standards relating to persons engaged in trade, welcomes the industrial magnate, and his vast wealth and love of ostentation have set the pace for lavish expenditure. Trade is the dominant phase of American life, – the divine process by which, according to current opinion, “the whole creation moves,” – and, as it has achieved the conquest of most of our social institutions and of our political powers, that it should also dominate “society” is but a natural sequence. Flaunting and garish consumption becomes the basic canon in fashionable affairs. As Mr. Thorstein Veblen, in his keen satire, “The Theory of the Leisure Class,” puts it: —

“Conspicuous consumption of valuable goods is a means of reputability… As wealth accumulates on his [the magnate’s] hands, his own unaided effort will not avail sufficiently to put his opulence in evidence by this method. The aid of friends and competitors is therefore brought in by resorting to the giving of valuable presents and expensive feasts and entertainments. Presents and feasts had probably another origin than that of naïve ostentation, but they acquired their utility for the purpose very early, and they have retained that character to the present.”

The conspicuous consumption of other days was, however, as compared with that of the present, but a flickering candle flame to a great cluster of electric lights. Against the few classic examples, such as those of Cleopatra and Lucullus, our present aristocracy can show hundreds; and the daily spectacle of wasteful display might serve to make the earlier Sybarites stare and gasp. Present-day fashionable events come to be distinguished and remembered not so much on the score of their particular features as of their cost. A certain event is known as Mr. A’s $5,000 breakfast, another as the Smith-Jones’s $15,000 dinner, and another as Mrs. C’s $30,000 entertainment and ball.

Conspicuous eating becomes also a feature of seigniorial life. The “society” and the “yellow” journals are crowded with accounts of dinners and luncheons, following one after another with an almost incredible frequency. And not only is the frequency remarkable, but the range and quantity of the viands furnished almost challenge belief. So far, it is believed, the journals which usually deal in that sort of news have neglected to give an authoritative menu for a typical day in the life of a seigniorial family. We have dinner menus, luncheon menus, and so on, but nothing in the way of showing what is consumed by the individual or family during a term of twenty-four hours. Some light on the subject, however, is furnished by Mr. George W. E. Russell, the talented author of “Collections and Recollections,” in his recent volume, “An Onlooker’s Note-book.” Objection may be made to the effect that Mr. Russell is an Englishman, and that he is describing an English royal couple. But the demurrer is irrelevant, since it is well known that our seigniorial class founds its practices and its canons (excepting only the canon regarding persons engaged in trade) upon English precedents, and that English precedents are made by the Royal Family. And not only does our home nobility imitate English models, but it piles Pelion upon Ossa, and seeks constantly to outshine and overdo the actions of its transatlantic cousins. Mrs. George Cornwallis-West (formerly Lady Randolph Churchill) recently stated that the vast sums spent by Americans in England have lifted the standard of living to a scale of magnificence almost unknown before. So for whatever is shown to be English custom, something must be added for American improvement and extension when assuming its transplantation to these shores. Mr. Russell writes: —

“A royal couple arranged to pay a two nights’ visit to a country house of which the owners were friends of mine. For reasons of expediency, we will call the visitors the duke and duchess, though that was not their precise rank. When a thousand preparations too elaborate to be described here had been made for the due entertainment of them and their suite and their servants, the private secretary wrote to the lady of the house, enclosing a written memorandum of his royal master’s and mistress’s requirements in the way of meals. I reproduce the substance of the memorandum – and in these matters my memory never plays tricks. The day began with cups of tea brought to the royal bedroom. While the duke was dressing, an egg beaten up in sherry was served to him, not once, but twice. The duke and duchess breakfasted together in their private sitting room, where the usual English breakfast was served to them. They had their luncheon with their hosts and the house party, and ate and drank like other people. Particular instructions were given that at 5 o’clock tea there must be something substantial in the way of eggs, sandwiches, or potted meat, and this meal the royal couple consumed with special gusto. Dinner was at 8.30, on the limited and abbreviated scale which the Prince of Wales introduced – two soups, two kinds of fish, two entrées, a joint, two sorts of game, a hot and cold sweet, and a savory, with the usual accessories in the way of oysters, cheese, ice, and dessert. This is pretty well for an abbreviated dinner. But let no one suppose that the royal couple went hungry to bed. When they retired, supper was served to them in their private sitting room, and a cold chicken and a bottle of claret were left in their bedroom, as a provision against emergencies.”

All the men of great wealth are not men of leisure. Some of them work as hard as do common laborers. For such as these the tremendous gastronomy recounted by Mr. Russell would be impossible as a daily exercise. When, therefore, it is assumed of any of our seigniorial class, it must be limited to magnates on vacation, to their leisurely sons, nephews, hangers-on, and women, and to those who have retired from active pursuits. But there are other canons of social reputability besides personal leisure and personal wasteful consumption. These are, to quote again from Mr. Veblen, vicarious leisure and vicarious consumption – the leisure and lavishness of wives, sons, and daughters. It is these who, in large part, at New York, Lenox, and Newport, support the social reputation of their seigniorial husbands and fathers. The “dog parties,” wherein the host “puts on a dog collar and barks for the delectation of his guests,” the “vegetable parties,” wherein host and guests, perhaps from some latent sense of inner likeness, make themselves up to represent cabbage heads and other garden products, the “monkey parties,” the various “circuses” and like events, are given and participated in more generally by the vicarious upholders of the magnate’s social reputation than by the seignior himself.

But in ways more immediate – by means which do not conflict with his daily vocation – the working magnate gives signal example of that virtue of capitalistic “abstinence” which is the foundation of orthodox political economy. The splendors of his town house, his country estate, and his steam yacht, to say nothing of his club, are repeatedly described to us in the columns of popular periodicals. His paintings, decorations, and bric-à-brac, his orchids and roses, his blooded animals and his $10,000 Panhard, are depicted in terms which make one wonder how paltry and mean must have been the possessions of Midas and how bare the “wealth of Ormus and of Ind.” And when, for a time, he lays down the reins of power, and betakes himself to Saratoga or Newport or Monte Carlo, yet more wonderful accounts are given of his lavish expenditure. The betting at the Saratoga race-tracks last August is reported to have averaged $2,000,000 a day. “The money does not come,” said that eminent maker of books, Mr. Joe Ullman, “from any great plunger or group of plungers, but from the great assemblage of rich men who are willing to bet from $100 to $1,000 on their choices in a race.” On the transatlantic steamers, in London and in Paris, the same prodigality is seen. A king’s ransom – or what is more to the point, the ransom of a hundred families from a year’s suffering – is lost or won in an hour’s play or lightly expended for some momentary satisfaction.

IV

There remain for brief mention the benefactions of the magnates. Most of these come under the head of “conspicuous giving.” Gifts for educational, religious, and other public purposes last year reached the total of $107,360,000. In separate amounts they ran all the way from the $5,000 gift of a soap or lumber magnate to the $13,000,000 that had their origin in steel. It is an interesting list for study in that it reveals more significantly than some of the instances given the standards and temper of the seigniorial mind. An anonymous writer, evidently of Jacobinical tendencies, some time ago suggested in the columns of a well-known periodical a list of measures for the support of which rich men might honorably and wisely devote a part of their fortunes: —

“He [the rich man] could begin by requiring the assessors to hand him a true bill of his own obligations to the public. He could continue the good work by persuading the collector to accept a check for the whole amount. This would make but a small draft upon his total accumulations. A further considerable sum he could wisely devote to paying the salaries of honorable lobbyists, who should labor with legislative bodies to secure the enactment of just laws, which would relieve hard-working farmers, struggling shopkeepers, mechanics trying to pay for mortgaged houses, and widows who have received a few thousand dollars of life insurance money, from their present obligation to support the courts, the militia, and other organs of government that protect the rich man’s property and enable him to collect his bills receivable. Finally, if these two expenditures did not sufficiently diminish his surplus, he could purchase newspapers and pay editors to educate the public in sound principles of social justice, as applied to taxation and to various other matters.”

Perhaps it is not singular that no part of the gifts of the great magnates is ever devoted to any of these purposes. Doubtless they see no flaw, or at least no remediable defect, in the present industrial régime. It is the régime under which they have risen to fortune and power, and it is therefore justified by its fruits. Their benefactions are thus always directed to a more or less obvious easement of the conditions of those on whom the social fabric most heavily rests. Hospitals, asylums, and libraries are the objects, though recently a bathing beach for poor children has been added to the list. The propriety of securing learned justification of the existing régime causes also a considerable giving to schools, colleges, and churches. But nowhere can there be found a seigniorial gift which, directly or indirectly, makes for modification of the prevailing economic system.

CHAPTER IV

Our Farmers and Wage-earners

The increasing dependence of middleman and petty manufacturer has already been considered. The same pressure which bears upon these bears also upon farmer and wage-earner. The editorials and the oratory of election years, it is true, supply us with recurring pæans over the independence, the self-reliance and the prosperity of these classes, and such graphic tropes as “the full dinner pail” and “the overflowing barn,” become the party shibboleths of political campaigns. Plain facts, however, accord but ill with this exultant strain.

I

In most ages the working farmer has been the dupe and prey of the rest of mankind. Now by force and now by cajolery, as social customs and political institutions change, he has been made to produce the food by which the race lives, and the share of his product which he has been permitted to keep for himself has always been pitifully small. Whether Roman slave, Frankish serf, or English villein; whether the so-called “independent” farmer of a free democracy or the ryot of a Hindu prince, the general rule holds good. Occasionally, by one means or another, he gains some transitory betterment of condition; the Plague of 1349 and the Peasants’ Rebellion of 1381 won for his class advantages which were retained during three generations. But in the long run he is the race’s martyr. Under a military autocracy his exploitation was inevitable. There is no reason for it now, for the lives and well-being of the rest of mankind are in his hands: were the working farmers organized as the manufacturers and the skilled artisans are organized, and could they lay by for themselves a year’s necessities, they could starve the race into submission to their demands. But the thing is not to be; nor, indeed, is any marked change to their advantage likely to happen, for, so far as current tendencies point, the future is to repeat the past.

In our day and in our land both force and cajolery conspire to keep the peasant farmer securely in his traces. He cannot break through the cordon which the trusts and the railroads put about him; and even if he could he would not, since the influences showered upon him are specifically directed to the end of keeping him passive and contented. Our statisticians assure him of his prosperity; our politicians and our moulders of opinion warn him of the pernicious influence of unions like the Farmers’ Alliance, and further preach to him the comforting doctrine that by “raising more corn and less politics” he will ultimately work out a blissful salvation. Sometimes he must burn his corn for fuel; often he cannot sell his grain for the cost of production, even though many thousands of persons in the great cities may be hungering for it; frequently he cannot afford to send his children to school, and in a steadily increasing number of cases he is forced to abandon his farm and become a tenant or a wanderer. He is puzzled, no doubt, by these things; but they are all carefully and neatly explained to him from the writings and preachments of profound scholars, as “natural” and “inevitable” phenomena. His ethical sense may be somewhat disturbed by the explanations, but he learns that it is useless to protest, and he thereupon acquiesces.

A sort of symposium on the joys of the farmer is to be found in the September number of the American Review of Reviews. Mr. Clarence H. Matson writes of improved conditions due to rural free delivery of mails and a few other reforms; Mr. William R. Draper dilates upon the enormous revenues which have flowed to the farmers during the current year, and Professor Henry C. Adams contributes a symphony on the diffusion of agricultural prosperity. A fourth article, by Mr. Cy Warman, furnishes a rather discordant note to the general harmony, since it shows a large and increasing immigration of our prosperous farmers into Canada. Some 20,000 crossed the border last year, according to Mr. Warman, while during the first four months of 1902, 11,480 followed, and indications pointed to a total of 40,000 emigrants for the present year. The official figures of the Canadian Government, since published, partly confirm these estimates. The number of immigrants from the United States for the year ended June 30, 1902, was 22,000. The number for the current year will probably be larger, for according to a Montreal press despatch of September 17th: “The immigration from the American to the Canadian Northwest has assumed much greater proportions this year than ever before, and land sales to Americans are daily reported. The latest large sale is by the Saskatchewan Valley Land Company, which has sold 100,000 acres in Saskatchewan to an American syndicate for $500,000.”

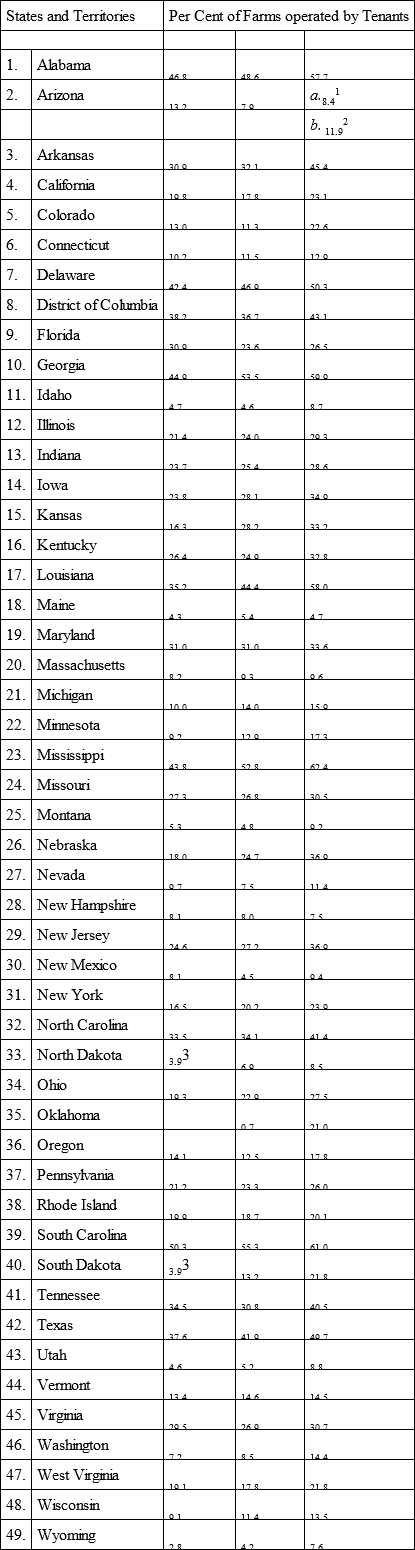

“The American farmer,” sententiously and truthfully remarks Professor Adams, “does not hoard his cash.” He gives no reason for the fact, and the determination must be left to the reader. “The American farmer,” he further remarks, “is, as a rule, his own landlord.” This statement reveals a very serious misapprehension of the facts. Something more than every third farm in the United States, according to the recent census, is operated by a tenant. Moreover, the proportion of tenants is constantly rising. For the whole country, tenants operated 25.5 per cent of all farms in 1880, 28.4 per cent in 1890, and 35.3 per cent in 1900. Further, the tendency is not confined to particular sections, but is common to the whole country. During the last decade the number of tenant-operated farms increased relatively to the whole number of farms in every State and Territory except Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire. In Maine tenantry decreased seven-tenths of 1 per cent, in New Hampshire five-tenths of 1 per cent, and in Vermont one-tenth of 1 per cent. For the twenty-year period, as was pointed out in Chapter II, the only exceptions to the general increase are Arizona, Florida, and New Hampshire.

The recent census, out of its abundant optimism, does not segregate these facts, and makes no general comment other than that tenantry has increased and that salaried management is believed to be “constantly increasing.” The bulletin on “Agriculture: The United States” does not even furnish a general classified summary of the data on tenantry. But the separate reports give the statistics, and out of them the following table is compiled: —

INCREASE OF FARM TENANTRY

1 Including Indian farms

2 Excluding Indian farms.

3 Dakota Territory.

There were 2,026,286 tenants in 1900, an increase in twenty years of 97.7 per cent. There were 3,713,371 owners, part owners, “owners and tenants,” and managers, an increase in twenty years of 24.4 per cent. During the twenty-year period owners in Washington increased less than fivefold, tenants tenfold. Utah shows a doubling of the number of owners, and a quadrupling of the number of tenants. South Dakota, compared with Dakota Territory in 1880, reveals an increase of owners of two and one-half times; of tenants, eighteen times. There are 28,669 fewer owners in New York State than in 1880, and 14,331 more tenants. Ownership has declined and tenantry advanced, both absolutely and relatively, in New Jersey. The great farming State of Illinois has 15,044 fewer owners and 23,454 more tenants than in 1880, and even the young Territory of Oklahoma, wherein one might expect to find evidences of increased ownership, reveals, for the ten-year period, a two-hundred-fold increase of tenantry and only a sixfold increase of ownership.