полная версия

полная версияThe Man of Genius

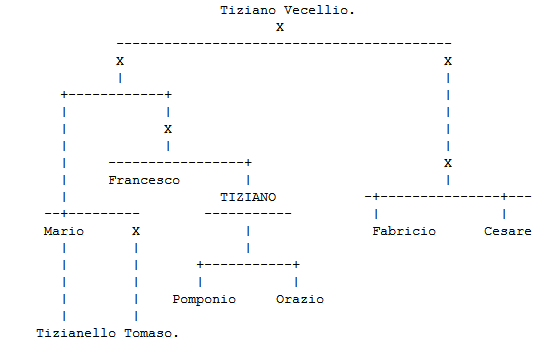

Among musicians may be named the Adams, the Coustons, the Sangallos; among painters, the Van der Weldes, the Coypels, the Van Eycks, the Murillos, the Veroneses, the Bellinis, the Caraccis, the Correggios, the Mieris, the Bassanos, the Tintorettos, the Caliaris, the Vanloos, the Teniers, the Vernets, and especially the Titians who produced a race of painters, as shown in the following genealogy taken from Ribot’s excellent book: —

Among poets may be noted Bacchylides, the nephew of Simonides and uncle of Æschylus who again had sons and nephews who were poets; Manzoni, the nephew of Beccaria; Lucan, the nephew of Seneca; Tasso, the son of Bernardo; Ariosto, with a brother and nephew poets; Aristophanes, with two sons who wrote comedies; Corneille, Racine, Sophocles, Coleridge, who had sons and nephews who were poets; the Dumas, father and son; the brothers Joseph and André Chenier, Alphonse and Ernest Daudet.

In the natural sciences we find the two Plinies, uncle and nephew, the families of Darwin, Euler, De Candolle, Hooker, Herschel, Jussieu, Saussure, Geoffroy St. Hilaire. Among philosophers we find the Scaligers, the Vossius, the Fichtes, and the brothers Humboldt, Schlegel and Grimm; among statesmen the Pitts, Foxes, Cannings, Walpoles, Peels, and Disraelis; among archæologists, the Viscontis. Aristotle, himself the son of a scientific physician, had sons and nephews who were men of science. Cassini, an astronomer, had a son, who was a celebrated astronomer, a grandson who was a member of the Academy of Sciences at the age of twenty-two, and a more remote relation who was a distinguished naturalist and philologist.

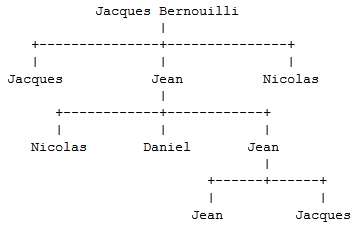

Here is the genealogical tree of the Bernouilli family: —

All the members of this family were distinguished in some science; at the beginning of this century there was a Bernouilli who was a chemist of some distinction; and in 1863 there still lived at Bâle Christophe Bernouilli, a professor of the natural sciences.

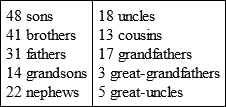

Galton, in a work of great value, but in which he often commits the mistake (from which I also cannot free myself) of confusing talent with genius, calculates a proportion of 425 men of ability to a million among the male population over fifty years of age, and the more select part of them as 250 to a million. Dealing with 300 families, containing 1000 eminent men, he concludes that the percentage of eminent kinsmen in these families would be as follows: —

The probabilities of kinsmen of illustrious men rising to eminence are – 15½ to 100 in the case of fathers; 13½ to 100 in the case of brothers; 24 to 100 in the case of sons.

Galton remarks that these figures vary, according as we are concerned with artists, diplomatists, soldiers, &c.

I am not, however, inclined to believe that this immense accumulation of fact authorizes us to accept a hereditary influence in genius as complete as in insanity. In the first place, in insanity the hereditary influence is exercised in a more intense and decisive manner, as 48 to 80; and then if Galton’s law applies to judges and statesmen, among whom adulation and the fetishistic adoration of a party or a caste can raise the son or grandson of a great man far above his merits, it is quite otherwise with artists and poets, who present an exaggerated hereditary action in brothers and sons and especially nephews, but very little in grandparents and uncles. And while in the heredity of genius the masculine sex prevails over the feminine in the proportion of 70 to 30, in the heredity of insanity there is scarcely any difference between the two sexes.256

Many men of genius have been thought to inherit from their mothers: such are Cicero, Condorcet, Cuvier, Buffon, Goethe, Sydney Smith, Cowper, Napoleon, Cromwell, Chateaubriand, Scott, Byron, Lamartine, Saint Augustine, Gray, Swift, Fontenelle, Ballanche, Manzoni, Kant, Wellington, Foscolo. On the other hand, Bacon, Raphael, Weber, Schiller, Milton, Alberti, Tasso, are said to inherit from their fathers. Yet, it may be asked, what was the celebrity of these fathers and mothers that one can feel assured they transmitted any genius to their children? Among most men of genius, also, there can be no heredity because of the predominance of sterility and of degeneration, of which the aristocracy furnishes us with a remarkable proof.257

With a few exceptions, then, such as the Darwins, the Cassinis, the Bernouillis, the Saint Hilaires, the Herschels, men of genius only transmit to their descendants a slight tendency magnified in our eyes by the prestige of a great name: —

“Rare volte risurge per li ramiL’umana probitate.”258Who thinks of Tizianello beside Titian, of Nicomachus beside Aristotle, of Orazio Ariosto beside his great uncle; or of the worthy professor Christophe beside his great ancestor Jacques Bernouilli?

Insanity, on the other hand, is often completely transmitted, or even with greater intensity, to succeeding generations. Cases of hereditary insanity in children and grandchildren, the form of insanity often being the same as in the ancestor, are very numerous. All the descendants of a Hamburg noble, whom history registers as a great soldier, were struck by insanity at the age of forty.259 At Connecticut Asylum eleven members of the same family have arrived in succession.260

A watchmaker, having recovered from an attack of insanity caused by the revolution of 1789, finally poisoned himself: later on his daughter became insane, and fell into a state of dementia; one of his brothers struck a knife into his own abdomen; another became a drunkard and died on the roadside; a third refused food and perished from starvation; his sister, who was of good health, had a son who was an epileptic lunatic, a daughter who became insane after her confinement and rejected food, an infant who refused to be suckled, and two others who died of cerebral diseases.

In a family studied by Berti, in four generations of about eighty individuals descended from an insane melancholiac we find ten subject to insanity, nearly always melancholia, nineteen who were neurotic, three who had special ability and three with criminal tendencies. The disorder was aggravated in the later generations and developed at an earlier age. In the third and fourth branches, the insane and neurotic appeared in every generation; in the others, the hereditary influence passed over one generation in the men and two in the women.

The history of the so-called “Jukes” family261 shows that such an influence may be still more powerfully developed, especially in association with alcoholism. From the head of the family, Max Jukes, a great drunkard, descended, in 75 years, 200 thieves and murderers, 280 invalids attacked by blindness, idiocy, or consumption, 90 prostitutes and 300 children who died prematurely. The various members of this family cost the state more than a million dollars.

These are not isolated facts. But in what families can we find genius so fatally and progressively fruitful?

Flemming and Demaux, again, have shown that not only do drunkards transmit to their descendants, tendencies to insanity and crime, but that even habitually sober parents, who at the moment of conception are in a temporary state of drunkenness, beget children who are epileptic or paralytic, idiotic or insane, very often microcephalic, or with remarkable weakness of mind which at the first favourable occasion is transformed into insanity.262 Thus a single embrace, given in a moment of drunkenness, may be fatal to an entire generation.

What analogy can we find here with the rare and nearly always incomplete heredity of genius?

The Criminal and Insane Parentage and Descent of Genius.– The parallelism of genius to insanity is, however, still present. We find that many lunatics have parents of genius, and that many men of genius have parents or sons who were epileptic, mad, or, above all, criminal. It is sufficient to study the history of the Cæsars, of Charles V., of Peter the Great. We see a progressive degeneration in crime and insanity in relations or children, rather than any conservation or increase of genius. This fact confirms a posteriori the degenerative character of genius; and at the same time reveals the relationship which it generally has with moral insanity. Commodus, son of the virtuous Marcus Aurelius, was a monster of cruelty. The son of Scipio Africanus was an imbecile, the son of Cicero a drunkard. Luther’s son was insubordinate and violent; William Penn’s was a debauched scoundrel. Themistocles, Aristides, Pericles, Thucydides were unhappy in their children.

Cardan had two sons who were criminals; one, of great ability, was condemned to death for poisoning; the other, given up to gaming, drinking, and thieving, was successively imprisoned at Pavia, Milan, Cremona, Bologna, Piacenza, Naples. When arrested he would promise reformation, but as soon as he was free he at once returned to his old habits, and even calumniated his father and attempted to get him imprisoned.263 Cardan’s father was eccentric and stammered; he did not dress like other people, and pursued various strange studies; he had lost some part of his skull in consequence of a wound received in youth, and he believed that he was guided by a spirit. His mother was irascible; when pregnant with him she attempted to abort.264

It appears that Aretino’s mother was a prostitute. Petrarch had a lazy and vicious son, “the most refractory to letters that man of letters ever had;” he died at the age of twenty-four.265 Rembrandt brought up his son Titus, with great care, to be an artist; but in spite of all efforts he could make nothing of him. Walter Scott’s son, a cavalry officer, was ashamed of his father’s literary celebrity, and boasted that he had never read one of his novels. Mozart’s son, when asked by Bianchini if he liked music, replied by throwing a handful of gold on the table: “That is the only music I like!” Sophocles’ son tried to represent his old father as imbecile. Frederick the Great’s father was morally insane and a drunkard; Peter the Great had a son who was a drunkard and maniacal; Richelieu’s sister imagined that her back was made of crystal; his brother thought he was God the Father; Niccolini’s sister thought she was damned because of her brother’s heresy, and attempted to kill him; Hegel’s sister was insane, as also was Diderot’s; Lamb’s sister killed her mother during a maniacal attack. Gray’s father was a worthless scoundrel, who used to beat his wife, by whose exertions the children were supported. Thomas Campbell’s only son was hopelessly imbecile.

Charles V.’s mother suffered from melancholia; his grandchildren and great-grandchildren were also insane: Don Carlos, brutal, cruel, and turbulent; Philip III., subject to convulsions; Charles II., an imbecile epileptic, with whom the race was extinguished; and Alexander Farnese, a bastard grandson of eccentric genius.266

The drunkenness of Beethoven’s father was notorious. Byron’s mother was half-mad; his father, known as “mad Jack Byron,” was dissolute and eccentric, and is said to have committed suicide. It has been said of Byron that if ever there was a case in which hereditary influence could justify eccentricity of character it was his, for he was descended from individuals in whom everything seemed calculated to destroy harmony of character and domestic peace. Alexander had a dissolute and perverse mother, a drunken father. Plutarch’s grandfather was much given to wine, of which he delighted to celebrate the virtues; and Cimon’s was a drunkard and debauched. Kerner had a maternal uncle who was mad; his sister was melancholic and had two children, of whom one was insane, the other a somnambulist.267 The sons of Tacitus, Carlini, Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, Mercadante, Donizetti, Volta, Manzoni, a daughter of Victor Hugo, the father and brothers of Villemain, the sister of Kant, the brothers of Zimmermann, Perticari, and Puccinotti were all insane. D’Azeglio, who had a grandfather and a brother more than eccentric, records a saying current at Turin: “I Taparei a l’an nen le grumele a port.”268

The origins of Renan’s neurosis, of which I have already spoken, he has himself indicated in speaking of his religious and prematurely sacerdotal education, that education of the seminary which when it once takes hold of a man never more leaves him, and which is so productive of insanity. The alienist will find other sources of neurosis and atavism in the little town of Tréguier in which Renan was born. On account of the frequency of consanguineous marriages and of the preponderance of the ecclesiastical element, the place swarmed with the insane and semi-insane. “These inoffensive lunatics,” he writes, “were a sort of institution, a municipal affair. We said, ‘our lunatics,’ as at Venice they say ‘nostre carampane.’ One met them nearly everywhere; they saluted you, greeted you with some nauseous pleasantry, which yet raised a smile. They were liked, and they were useful. I shall always remember the good lunatic Brian, who imagined that he was a priest, and passed part of the day in church, imitating the ceremonies of the mass; all the afternoon the cathedral was filled with a nasal murmur; it was the poor lunatic’s prayer, well worth any other.”269 A still greater influence on Renan’s psychosis must be attributed to the insanity in his own family. His paternal uncle, semi-insane, passed his days and nights at inns telling stories and legends to the peasants with whom he was a great favourite; one night he was found dead on the roadside. His grandfather, an ardent and honest patriot, lost his reason in 1815, through grief, and used to walk about with an enormous tricoloured cockade, exclaiming: “I should like to know who would dare to snatch from me this cockade!” He himself, a seven-months’ child, remained for a long time small and weak, and for this reason was the more easily disturbed by a sacerdotal education, which inflames, like a hot iron, even the most tranquil spirits.

In Schopenhauer, also, the insane and neurotic hereditary tendency was well marked. On his father’s side he was descended from an old family of Dantzig merchants; his great-grandfather was a man of very strong and energetic character; his grandfather, a man of quiet business habits, seems to have brought the property into the family, but the grandmother had an aunt and a grandmother who were insane. Schopenhauer’s father seems to have been a skilled man of business; a republican, he possessed the native arrogance of a democratic patrician; inclined to deafness from childhood, he had attacks of rage from which even the domestic dog and cat fled terrified. With the increase of his deafness he became more irritable, and suffered, if not from actual insanity, at least from morbid fears. It was suspected that he committed suicide. He presented various characters of degeneration: large ears, very prominent eyes, thick lips, a short, up-turned nose; he was, however, of considerable height. Schopenhauer’s mother, married at the age of nineteen, was witty and ambitious, and, as he himself said, very frivolous. His brother was imbecile from childhood.

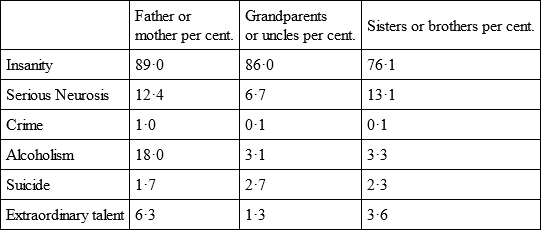

This influence of insane heredity can to-day be controlled by statistics. The Prussian statistics for 1877 show that among 10,676 lunatics, morbid heredity may be traced in 6,369.270 They are divided as follows: —

This seems to show that a considerable number of lunatics are descended from men of ability. The number of brothers and sisters of lunatics endowed with ability, surpassing that of suicidal, alcoholistic, or criminal brothers confirms the influence. In twenty-two cases of hereditary insanity Aubonel and Thoré observed two cases of sons of ability.271

These facts were not unknown to old observers. Tassoni, a very original writer, in his Pensieri Diversi (1621) discusses the question: “How it happens to wise fathers to have very foolish children, and to very foolish fathers to have very wise children.” Among the former he mentions the sons of Scipio Africanus, Anthony, Cicero, Agrippa Posthumus, Claudius the son of Drusus, Caligula, of Germanicus, Commodus, of Marcus Aurelius, Lamprocles, of Socrates, Arrhidaeus, of Philip. Among many opinions, more or less extravagant, of learned men of his time, he reports one to the effect that “in great men the vital spirits assemble at the brain to fortify and give vigour to the powers of the intelligence; it happens in consequence that the blood and sperm remain cold and languid, and the children of such men, especially the males, are inclined to stupidity.”

Age of Parents.– This is one of the hereditary influences which often escape from view, and are at present not clearly seen. Marro has shown the great influence of the advanced age of the parents on the intelligence or the insanity of the children. Very great is the number of men of genius, and even of talent, issued from aged fathers: Frederick II., Napoleon I., Sciacci, Bizzozzero, Rochefort, Dumas père, A. Jussieu, Balzac, J. Cassini, C. Vernet, Beaconsfield, Horace Walpole, William Pitt, Racine, Adler, Auriac, Béclard, Schopenhauer. From young fathers I have, on the other hand, only found Victor Hugo, De Girardin, Arneth, Barral, Bertillon, Ségur. This influence may explain the longevity of men of genius.

Conception.– De Candolle speaks of the influence which strong passion on the part of the parents at conception may have on the offspring, and recalls the considerable number of bastards of genius. Erasmus boasted that he was not the fruit of wearisome conjugal duty. Isaac Disraeli wrote in his “Memoirs of Toland” that birth outside marriage creates strong and resolute characters. Among illegitimate sons were: Themistocles, Charles Martel, William the Conqueror, the Duke of Berwick whom Montesquieu called the perfect man, Leonardo da Vinci, Boccaccio, A. Dumas, Cardan, D’Alembert, Savage, Prior, De Girardin, La Harpe, Alexander Farnese, Dupanloup.272 Newton was conceived after his parents had spent two years of forced continence. It will be seen from these and other facts how far we are yet from having exhausted the numerous sources of hereditary genius.

Those who recall how many men of genius have been born of consumptive and drunken parents, and who know how these two forms of degeneration are often transformed in the children into moral insanity, will perceive that there can be other hereditary causes of genius which escape ordinary observers, and are, therefore, little known.

CHAPTER IV.

The Influence of Disease on Genius

Spinal diseases – Fevers – Injuries to the head and their relation to genius.

Gérard de Nerval in his book, Le Rêve et la Vie, after having confessed that he often wrote in a state of morbid exaltation, adds that the old saying Mens sana in corpore sano is false, for many powerful minds have been allied to weak and diseased bodies.

Conolly treated a man whose intelligence was aroused by the use of blisters, and another whose ability was called forth during the initial period of phthisis and gout. Cabanis, Tissot, and Pomme observe that certain febrile conditions provoke extraordinary mental activity. Sylvester remarks that during the nocturnal fever of what he describes as a fortunate attack of bronchitis he was enabled to reach the solution of a mathematical problem.273

A man of genius, Maine de Biran, who was always ill, well expresses the influence of infirmities on genius, “The feeling of existence,” he writes, “is not found among the majority of men because with them it is continuous; when a man does not suffer he does not think of himself; disease alone and the habit of reflection enable us to distinguish ourselves.”

It has frequently happened that injuries to the head and acute diseases, those frequent causes of insanity, have changed a very ordinary individual into a man of genius. Vico, when a child, fell from a high staircase and fractured his right parietal bone. Gratry, a mediocre singer, became a great master, after a beam had fractured his skull. Mabillon, almost an idiot from childhood, fell down a stone staircase at the age of twenty-six, and so badly injured his skull that it had to be trepanned; from that time he displayed the characteristics of genius. Gall, who narrates this fact, knew a Dane who had been half idiotic, and who became intelligent at the age of thirteen, after having rolled head foremost down a staircase.274 Wallenstein was looked upon as a fool until one day he fell out of a window, and henceforward began to show remarkable ability. Some years ago, a cretin of Savoy, having being bitten by a mad dog, became very intelligent during the last days of his life. Cases have been recorded in which ordinary persons have displayed extraordinary intelligence after diseases of the spinal cord.275 “It is possible that my disease [of the spinal cord] may have given a morbid character to my later compositions,” wrote with true divination the unfortunate Heine. And the remark does not apply to his later writings only. “My mental excitement,” he wrote, some months before his condition had become aggravated, “is the effect of disease rather than of genius. I have written verses to appease my suffering a little… In this horrible night of senseless pain my poor head is flung backwards and forwards, shaking with pitiless gaiety the bells on my jester’s cap.”276 Béclard turned from mere theories to experiment, after a stroke of apoplexy.277 Pasteur’s greatest discoveries were made after a stroke of apoplexy. Bichat and Schroeder van der Kolk have observed that men with anchylosis of the neck possess remarkably bright intelligence. It is a common saying that the hump-backed are keen and malicious. Rokitansky sought to explain this by the resulting curve of the aorta, after giving origin to the vessels which supply the brain, the volume of the heart and the arterial pressure in the head being thus augmented.

CHAPTER V.

The Influence of Civilization and of Opportunity

Large Towns – Large Schools – Accidents – Misery – Power – Education.

However clearly such laws as we have examined may seem to be ascertained, the conclusions deduced from them must be accepted with a certain reserve; since there exists a series of factors, almost impossible to seize, which intercept and confound all these influences, not excepting even the orographic.

We have already seen how great agglomerations of individuals, whatever the climate and race, are sufficient to increase the number of artists and of talents. But might not this be a purely factitious effect, as, for instance, when individuals who have left their birthplace for some great capital (as often happens in the case of infants and invalids), are looked upon as natives of the latter? This becomes certain, if we remember the pernicious influence of great towns, and consider with Smiles, that the life of large towns is not favourable to intellectual work, that men who have had a great influence on their age have been brought up in solitude, and that all the great men of England, and even of London, were born in the country, though this fact is often ignored on account of their having fixed their residence in the capital. Carlyle says that a man born in London seems but the fraction of a man. We read, in the Lives of the Engineers, that all great English engineers have been country-bred.

The establishment of a school of painting, even when it is the result of an importation, makes an artistic centre of a place which was not so previously, and, if the establishment goes back to a very distant time, the number of artists becomes very large. Let us look, for example, at Piedmont, where, assuredly, a military education reinforced by climate and race, and, to a still greater degree, by clerical influence, retarded for a long time the development of the fine arts, and especially of music. Up to 1460, celebrated painters were not numerous in Piedmont, and the only ones to be found there were of foreign origin, such as Bono and Bondiforte. But Bondiforte, who had been sent for from Milan, was immediately followed by Sodoma, Martini, Giovannone, Vercellese. Ferro di Valduggia was followed by Lanini, and Tansi by Valduggia, in the same way as Viotti’s example attracted thither, within a short time, five celebrated violinists.