Полная версия

Inner City Pressure

While these new creations were honed by more experienced former junglists like Wiley and Geeneus, a younger generation, still in their mid-teens, were just starting out with making music, developing the new sound and their mic skills in schools and youth clubs. Grime as a genre, and a scene, was built on an astonishing level of youthful autonomy and self-sufficiency – but for all its entrepreneurial, DIY vigour and self-starting rhetoric, the state played a little-noticed role in some of its earliest developments. For one thing, there was the youth clubs. Dizzee describes an informal circuit of them as his apprenticeship on the mic, ‘going from youth club to youth club, it started there’ – they would travel to youth clubs in Canning Town (east London), Deptford (south-east) and further east to Beckton, Kano’s local. It was at Lincoln Arches youth club in Bow (long since closed down), part of the Lincoln North Estate, where Wiley, Dizzee, Nasty Crew and Ruff Sqwad among others would hang out, play table tennis and pool, and then sometimes be allowed to have raves, where they’d practise spitting over garage and proto-grime. ‘Friday night after school you’d think, “Yes, I need to go to the Linc, I need to go clubbing, I need to impress everyone and the girls there,”’ Tinchy Stryder recalled a few years later.

Another youth club, across the other side of Canary Wharf in the Isle of Dogs, was responsible for financing Ruff Sqwad’s first ever release, the squalling, punky ‘Tings In Boots’. ‘Obviously you needed money to put out a song, and we were still in school. Jeff and Jo, who ran that youth club on the Isle of Dogs, they were sort of the unsung heroes of grime,’ Rapid said. ‘They saw our talents, they sort of managed us, they thought yeah we’ll put a couple of hundred quid into actually bringing this out.’ Other times they’d pool their dinner money to fund their early vinyl releases. And the elders on the nascent local scene were always there to help them too, with advice, practical hands-on tips and financial support: ‘When we got further down the line with our productions, we used to go down to Jammer’s basement and give him the parts, I remember he was like, “Raps, Dirt, your tunes are banging, but you have to get mixdowns,” and we were like, “What’s that?” We didn’t know what that was! We were like “What do you do?” – by then he was already well into making grime and releasing records. From people like Jammer and Wiley we got a lot of energy around then.’

And then there was school, as a meeting point for practice, socialising and developing musical skills. Shystie’s transformative experience, taking her from hobbyist MC with a 9–5 job she hated, was the decision to study sound engineering at FE College, ‘[where] I realised: I could really do this!’ – after a whirlwind year, she signed to Polydor, and didn’t go back for the second year of the course. The most famous example of the importance of school comes from Dizzee Rascal’s teacher Tim Smith, who garnered some press attention after Boy in da Corner won the Mercury Prize in 2003; the story resonated as a redemptive one, of the singular faith of a mentor who refused to abandon hope – Dizzee had been expelled from two secondary schools already, and was placed at Langdon Park in Poplar, where Tim Smith was Head of Arts; he gave him the space to get on with his music, even after he had been expelled from all his other classes. Sent home from school one day for misbehaviour, angry and frustrated, Dizzee wrote some of his most well-known rave bars: ‘lyrical tank, box an MC like my name was Frank/going on dirty, going on stank.’16 ‘You could vent, I think that’s why I loved MCing,’ he told Radio 1 recently. The school was, like most state comprehensives, chronically short of resources, and the music department’s PCs had been donated by Morgan Stanley, and some of the other major banking corporations in Canary Wharf – via the LDDC, in fact.

On Dizzee’s first day, Smith left him to his own devices, sitting at a PC playing with Cubase. ‘After about 20 minutes, one of the pair of teachers said, “You’ve got to come over and see this.” Most kids are happy to have got a few bars down, but he had already zoomed ahead. He could quickly get information down, but what was most unusual was he would then spend a lot of time refining it – a lot of youngsters wanted to create music, but weren’t as interested in total refinement of a sound. He could string quite a complex rhythmic pattern together, in 20 to 30 minutes, but then be quite happy to spend a week refining and editing.’ On Monday evenings after school, a drop-in session funded by Tower Hamlets Summer University gave him a further opportunity to work on beats; Smith loaned Dizzee Philip Glass, Steve Reich and John Adams CDs, minimalist composers and favourites of his – there was some connection there, in the use of space, he thought. (Hyperdub founder and musical and academic polymath Steve ‘Kode9’ Goodman once said of dubstep that you should ‘dance to the gaps’, a sonic architecture which was shared with some of the more sparse early grime instrumentals, when neither had ‘taken the name’.)

Towards the end of Year 11, Dylan Mills was excluded from all his lessons, after more misbehaviour – but a forgiving headmaster knew that three expulsions, statistically, would most likely lead to a bad downwards spiral, and asked Smith if Dizzee could just sit quietly in the music room with him. So Dizzee would sit alone and work on his music for those last months, and occasionally help Smith teach Cubase to the Year 7s.

‘The music was awesome,’ Smith told me, who has retired from teaching, but now sits on the board of Rinse FM. ‘Nobody else had written music like that, with those really sharp, intricate beats, but sometimes just dropping out to nothing. And that is the hardest thing in music, to create space. And that showed particular talent, especially for someone so young, and you can hear it on Boy in da Corner, to know that you shouldn’t overload it. In Cubase you get quite a visual image of what you’re going to hear – and he would colour code, so you can see when something’s going to be repeated.’

Boy in da Corner was a significant development from the music he made at school, but those basics of creating space were definitely learned there. ‘The giveaways were the very very sharp beats,’ Smith told me. ‘He would compose at about 80bpm – most youngsters were into about 120 – but he would have a deliberately slow beat, so that you could sub-divide each beat, not into 2 but into 4. That’s where you get the really sharp, interesting sound. He would draw it in, so it was filled, and erase certain bits of it, so it had a gap. That’s where that unexpected break in the music came from.’

Many of Dizzee’s instrumental creations in his mid-teens were unfiltered, unvarnished beats, breaks and synths. He spun gold from the most basic and unadorned of sound palettes: the songs he wrote in Langdon Park School were constructed from their kit of a small mixer and Cubase software on the second-hand PCs, using the Cubase sound pack. Simplicity, and the idea of having the beat already ringing around his head, seemed to lead to a very methodical, straightforward composition process. It was the least of experimental techniques to achieve the most ‘experimental’ of sounds – an inborn tendency to the avant-garde, no oblique strategies required:

‘I was always fucking about with some weird noise,’ he said to me a decade or so later, in a break from rehearsing the Boy in da Corner revival show. ‘All the samples were just lined up on the keyboard, I never used an MPC, so each key is a different sample. Those times I would usually start with the drums. “I Luv U”, I definitely started with the drums, and then built around it.’ On both Boy in da Corner and Showtime there are moments that reject not only simple pop structures and sensibilities, but any ‘songiness’ at all – part of his desire to move London electronic music on from UK garage, Dizzee once said, was because it was ‘all too nice-sounding’. Even the regularity and order of a simple 8-bar grime track is absent from tracks like ‘Knock, Knock’, on Showtime, a beat that constantly splits off at awkward angles and refuses to settle down. On ‘Brand New Day’, from his debut, Dizzee juxtaposes the most desperately depressive, real-world lyrical narratives with production of breathtaking otherworldliness. It is almost indescribable: effortlessly light, like someone running their finger around the rim of a glass, but it also makes you queasy, like you’re spinning down a plughole, out of control. In Dizzee’s teenage hands, the Japanese three-stringed shamisen becomes something between an earworm and an inner-ear infection.

‘I think it’s really important that you shouldn’t be afraid to use something if you like it, no matter how fucked the sound,’ Dizzee told Sound on Sound magazine in 2004, explaining his use of the shamisen. ‘Some people process sounds too much, but to me, that defeats the object … I felt that it was a really interesting sound, which didn’t remind me of anything else. I like using sounds that are about as “out there” as they come.’

Tim Smith noted that when Dizzee arrived in his GCSE music class at 14 he was already very comfortable with creating clear structures, and balancing rhythm, bass and melody – that he knew what the song sounded like in his head already, and the only challenge would be making it a reality. Tellingly, and unusually, many of the vocal recordings on Boy in da Corner were first takes: Dizzee’s pirate-radio training – as well as the street hustle of practising in the playground or around the estate – meant he could just walk in and get it right first time. But that one-take skill also helps explain the album’s vocal rawness, and its freshness. ‘I’ll never forget da way you kept the faith in me, even when things looked grim,’ he wrote in tribute to Smith on the album sleeve. Smith casually mentioned to me that he still had 33 tracks Dizzee composed back then. ‘I couldn’t pass them on to anyone,’ he said, seeing the glint in my eye, but reassured me they were at least fully backed up (many classic instrumentals have been lost over the years in hard-drive meltdowns). We agreed maybe some kind of donation to the British Library sound archive would be in order.

It takes a village to raise a scene, and it gives that scene an extraordinary power and coherence when everyone in the village suddenly becomes obsessed with it. Appearing on Commander B’s Choice FM show in 2002, Wiley was asked about his ongoing beef with Durrty Doogz (later Goodz) – who did the fans think was winning, of the two of them? He told the radio host he ‘wasn’t really interested’ in what listeners in the world at large thought – there was only one audience which counted. ‘Home is where it matters,’ he said. ‘I care about my own area, I’d rather be the top boy in my own area – I want to be the top boy in east.’

MC Griminal, one of the younger of several members of the Ramsay family to become a key figure in the grime scene (older brothers Marcus Nasty and Mak 10 were founders and legendary DJs with Nasty Crew), tells a story of being an 11-year-old at St Bonaventure’s School in Forest Gate, when Tinchy Stryder, several years his senior, and already well known on the local scene, approached him, handed him a CD of his tracks, and a £10 note for his troubles, telling him to make sure Mak 10 got it. ‘None of my mates could believe that Tinchy was coming up to me, or that Dizzee was at my house,’ Griminal told local paper the Newham Recorder eight years later, in 2010. It was the era of hyper-local celebrity, even while almost all of the celebrities in question were living in cramped council homes with their parents, or sharing bedrooms with their siblings. When Slimzee’s gran went to the Woolworths on Roman Road, five minutes walk from their house, to buy his Bingo Beats CD, she saw two teenage girls enthusiastically pawing it. ‘That DJ Slimzee is my grandson,’ she told them, much to their excitement.

‘We started to become local-famous,’ Kano recalled in the Made in the Manor documentary. These years of dedicated community-based underground music making, in youth clubs, pirate-radio sets and house parties, made for a unique kind of apprenticeship, and a quietly confident mindset, once the stage unexpectedly became much bigger a few years later. ‘What helped when we broke through,’ Kano continued, ‘was the practice hours that we put in, performing in front of like, 20 people.’ When he was signed to 679, and was booked to do his first proper gig outside the manor, opening for The Streets, he wasn’t overly worried. ‘It was my first time performing in front of that many people, but I had put in so much hours, and made all my mistakes behind closed doors, that it was cool. We got to make our mistakes in someone’s kitchen, on a pirate radio.’

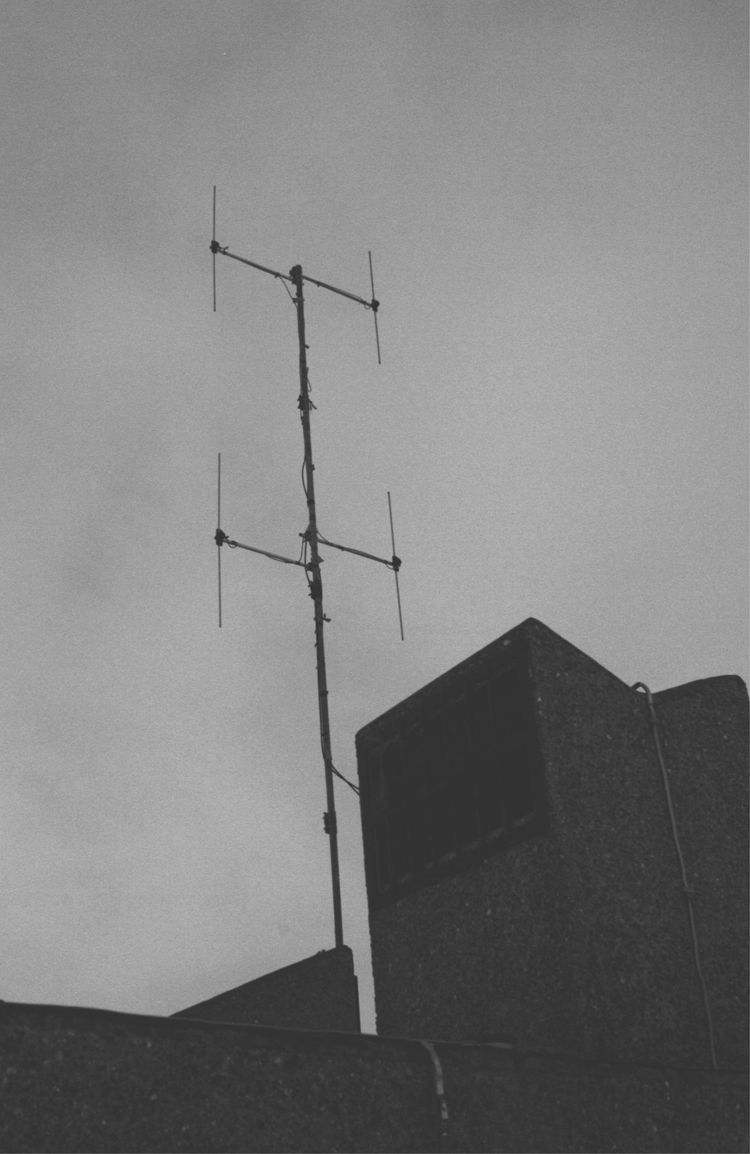

‘Let us know you’re locked.’ Rinse FM aerial, 2009

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.