Полная версия

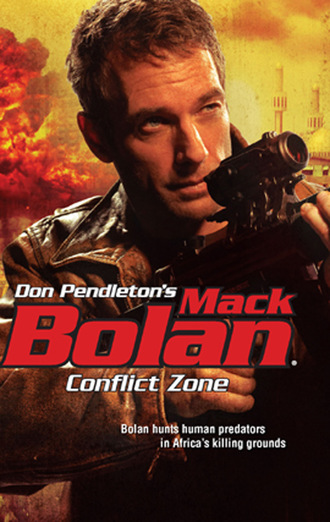

Conflict Zone

“Change of plans,” Bolan snapped. “Follow me.”

The Executioner turned and raced with the hostage toward a line of vehicles. A shot rang out behind them, followed instantly by a dozen volleys.

Turning, Bolan raked the compound with a long burst from his Steyr AUG. Mandy fumbled with her pistol, getting off several shots, yelping as a round stung her palm.

Reaching the motor pool, Bolan chose a jeep at random, slid behind the wheel and gunned its engine into snarling life as Mandy scrambled into the shotgun seat.

“Hang on!” he said, flooring the gas pedal, barreling through the middle of the camp to reach the access road—and freedom.

Conflict Zone

Mack Bolan®

Don Pendleton

www.mirabooks.co.uk

Pure good soon grows insipid, wants variety and spirit. Pain is a bitter-sweet, which never surfeits. Love turns, with a little indulgence, to indifference or disgust; hatred alone is immortal.

—William Hazlitt

“On the Pleasure of Hating” in

The Plain Speaker (1826)

I can’t stop hate. No one in history has come close, so far. But I can interrupt atrocities, beginning now.

—Mack Bolan

“The Executioner”

For Corporal Jason Dunham, USMC

April 14, 2004

God Keep

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

PROLOGUE

Esosa Village, Delta State, Nigeria

David Uzochi had been fortunate. He’d left home an hour before dawn to hunt, and he had been rewarded with a herd of topi when his ancient Timex wristwatch told him it was 8:13 a.m.

With game in sight, it came down to his skill with the equally ancient .303-caliber Lee-Enfield bolt-action rifle he carried, its nine-pound weight as familiar to Uzochi as the curve of his wife’s hip or breast.

He’d nearly smiled, thinking how pleased Enyinnaya would be when he brought home the meat, but he had caught himself in time, before the twitch of his lip or glint of sunlight on his white teeth could betray him to the grazing topi.

His first shot had been the only one he needed. As the other topi dashed away frantically to save themselves, Uzochi had been swift to clean his kill. There was no time to waste, when flies appeared to find a wound almost before the skin was broken, and the brutal sun began corrupting flesh before the last heartbeat had time to fade away.

The four-mile walk back to Esosa was a good deal shorter than his outward journey, since he was no longer seeking game, and he wouldn’t rest once along the way, despite the forty-something kilograms of flesh and bone draping his left shoulder. Uzochi drew a kind of buoyancy from his success, doubly thankful that he had meat enough to share with some of his neighbors.

The sound of the explosion made him break stride, pausing long enough to lock on its apparent point of origin.

The pipeline. What else could it be?

He cursed the Itsekiri bastards who were almost certainly responsible. Their war against pipelines and the pumping fields meant less than nothing to Uzochi, but he understood the Itsekiris’ hatred for his people, the Ijaw. And if this raid had brought them near Esosa…

Any doubt was banished from Uzochi’s mind when he saw the first black plume of smoke against the clear sky. The pipeline passed within a thousand yards of his village, and how could any Itsekiri cutthroat neglect such a target when it was presented?

Uzochi began to run, jogging at first, until he stabilized the topi’s deadweight to his new pace, then accelerating. He couldn’t sprint with the topi across his shoulders, and he never once considered dropping it.

Whoever managed to survive the raid would still need food.

Tears blurred his vision as he ran, thinking of Enyinnaya in the Itsekiris’ hands. Perhaps she’d seen or heard them coming and had fled in time.

A distant crackling sound of gunfire, now.

The sudden pain he felt was like a knife blade being plunged into his heart. It didn’t slow him, rather the reverse, but in his wounded heart David Uzochi knew he was too late.

Too late to save the only woman he had ever loved.

Too late to save the child growing inside her.

But, perhaps, not too late for revenge.

If he’d forgotten where the village lay, Uzochi could have found it by the smoke. When he was still a half mile distant, he could smell the smoke and something else. A stench of burning flesh that killed his appetite and made his stomach twist inside him.

It was over by the time he reached Esosa. Twenty minutes since he’d heard the last gunshots, and by the time he stood in front of the smoking ruins of his home, even the dust raised by retreating murderers had settled back to earth.

Uzochi didn’t need the dust, though. He could track his enemies as he tracked game, with patience that assured him of a kill.

He would begin as soon as he had dug a grave for Enyinnaya and their unborn child. As soon as he had cooked a flank steak from the topi over glowing coals that once had been his home.

He needed strength for the pursuit.

Strength, and the ancient Lee-Enfield.

It meant his death to track the Itsekiri butchers, but he wouldn’t die alone.

CHAPTER ONE

Bight of Benin, Gulf of Guinea

They had flown out of Benin, from one of those airstrips where money talked and no one looked closely at the customers or cargo. In such places, it was better to forget the face and name of anyone you met—assuming any names were given—and rehearse the standard lines in case police came later, asking questions.

Which plane? What men? Why would white men come to me?

“One minute to the beach,” the pilot said. His voice was tinny through the earphones Mack Bolan wore.

The comment called for no response, and Bolan offered none. He focused on the blue-green water far below him and the coastline of Nigeria approaching rapidly. He saw the sprawling delta of the Niger River, which had lent its name both to the country and to Delta State.

His destination, more or less.

“Still time to cancel this,” Jack Grimaldi said from the pilot’s seat. He spoke with no conviction, knowing from experience that Bolan wouldn’t cancel anything, but giving him the option anyway.

“We’re good,” Bolan replied, still focused on the world beyond and several thousand feet below his windowpane.

From takeoff, at the airstrip west of Cotonou, they’d flown directly out to sea. The Bight—or Bay—of Benin was part of the larger Gulf of Guinea, itself a part of the Atlantic Ocean that created the “bulge” of northwestern Africa. Without surveyor’s tools, no one could say exactly where the Bight became the Gulf, and Bolan didn’t count himself among the very few who cared.

His focus lay inland, within Nigeria, the eastern next-door neighbor of Benin. His mission called for blood and thunder, striking fast and hard. There’d been no question of his flying into Lagos like an ordinary tourist, catching a puddle-jumper into Warri and securing a guide who’d lead him to the doorstep of an armed guerrilla camp, located forty miles or so northwest of the bustling oil city.

No question at all.

Aside from the inherent risk of getting burned or blown before he’d cleared Murtala Muhammed International Airport in Lagos, Bolan would have been traveling naked, without so much as a penknife at hand. Add weapons-shopping to his list of chores, and he’d likely find himself in a room without windows or exits, chatting with agents of Nigeria’s State Security Service.

No, thank you, very much.

Which brought him to the HALO drop.

It stood for High Altitude, Low Opening, the latter part a reference to Bolan’s parachute. HALO jumps, coupled with HAHO—high-opening—drops, were known in the trade as military free falls, each designed in its way to deliver paratroopers on target with minimal notice to enemies waiting below.

In HALO drops, the jumper normally bailed out above twenty thousand feet, beyond the range of surface-to-air missiles, and plummeted at terminal velocity—the speed where gravity’s pull canceled out drag’s resistance—then popped the chute somewhere below radar range. For purposes of stealth, metal gear was minimized, or masked with cloth in the case of weapons. Survival meant the jumper would breathe bottled oxygen until touchdown. In HAHO jumps, a GPS tracker would guide the jumper toward his target while he was airborne.

“Four minutes to step-off,” Grimaldi informed him.

With a quick “Roger that” through his stalk microphone, Bolan rose and moved toward the side door of the Beechcraft KingAir 350.

It was closed. Bolan donned his oxygen mask, then waited for Grimaldi to do likewise before he opened the door. They were cruising some eight thousand feet below the plane’s service ceiling of 35,000, posing a threat of hypoxia that reduced a human being’s span of useful consciousness to an average range of five to twelve minutes. Beyond that deadline lay dizziness, blurred vision and euphoria that wouldn’t fade until the body—or the aircraft—slammed headlong into Mother Earth.

When Grimaldi was masked and breathing easily, Bolan unlatched the aircraft’s door and slid it to his left, until it locked open. A sudden rush of wind threatened to suck him from the plane, but he hung on, biding his time.

He was dressed for the drop in an insulated polypropylene knit jumpsuit, which he’d shed and bury at the LZ. Beneath it, he wore jungle camouflage. Over the suit, competing with his parachute harness, Bolan wore combat suspenders and webbing laden with ammo pouches, canteens, cutting tools and a folding shovel. His primary weapon, a Steyr AUG assault rifle, was strapped muzzle-down to his left side, thereby avoiding the Beretta 93-R selective-fire pistol holstered on his right hip. To accommodate two parachutes—the main and reserve chutes, hedging his bets—Bolan’s light pack hung low, spanking him with every step.

“Two minutes,” Grimaldi said.

Bolan checked his wrist-mounted GPS unit, which resembled an oversize watch. It would direct him to his target, one way or another, but he had to do his part. That meant making the most of his free fall, steering his chute after he opened it, and finally avoiding any trouble on the ground until he’d found his mark.

Easy to say. Not always easy to accomplish.

At the thirty-second mark, Bolan removed his commo headpiece, leaving it to dangle by its curly cord somewhere behind him. He was ready in the open doorway, leaning forward for the push-off, when the clock ran down. He counted off the numbers in his head, hit zero in a rush and stepped into space.

Where he was literally blown away.

EIGHT SECONDS FELT like forever while tumbling head over heels in free fall. It took that long for Bolan to regain his bearings and stabilize his body—by which time he had plummeted 250 feet toward impact with the ground.

He checked his GPS unit again, peering through goggles worn to shield his eyes from being wind-blasted and withered in their sockets. Noting that he’d drifted something like a mile off target since he’d left the Beechcraft, he corrected, dipped his left shoulder and fought the wind that nearly slapped him through another barrel roll.

Lateral slippage brought him back on target, hurtling diagonally through space on a northwesterly course. Bolan couldn’t turn to check the Beechcraft’s progress, but he knew Grimaldi would be heading back to sea, reversing his direction in a wide loop over the Gulf of Guinea before returning to the airstrip in Benin, minus one passenger.

The airfield’s solitary watchman wouldn’t notice—or at least, he wouldn’t care. He had been paid half his fee up front, and would receive the rest when the Stony Man pilot was safely on the deck, with no police to hector him with questions. Whether he had dumped Bolan at sea or flown him to the Kasbah, it meant less than nothing to the Beninese.

Twenty seconds in and he had dropped another 384 feet, while covering perhaps four hundred yards in linear distance. His target lay five miles and change in front of him, concealed by treetops, but he didn’t plan to cover all that distance in the air.

What goes up had to go down.

Bolan couldn’t have said exactly when he reached terminal velocity, but the altimeter clipped to his parachute harness kept him apprised of his distance from impact with terra firma.

Eleven minutes after leaping from the Beechcraft, Bolan yanked the rip cord to deploy his parachute. He’d packed the latest ATPS canopy—Advanced Tactical Parachute System, in Army lingo—a cruciform chute designed to cut his rate of descent by some thirty percent. Which meant, in concrete terms, he’d only be dropping at twenty feet per second, with a twenty-five-percent reduction in potential injury.

Assuming that it worked.

The first snap nearly caught him by surprise, as always, with the harness biting at his crotch and armpits. At a thousand feet and dropping, he was well below the radar that would track Grimaldi’s plane through its peculiar U-turn, first inland, then back to sea again.

And what would any watchers make of that, even without a Bolan sighting on their monitors? Knowing the aircraft hadn’t landed, would they then assume that it had dropped cargo or personnel, and send a squad of soldiers to investigate?

Perhaps.

But if they went to search the point where the Stony Man pilot had turned, they would be missing Bolan by some ten or fifteen miles.

With any luck, it just might be enough.

He worked the steering lines, enjoying the sensation as he swooped across the sky, with Africa’s landscape scrolling beneath his feet. Each second brought it closer, but he wasn’t simply falling down. Each heartbeat also carried Bolan northward, closer to his target and the goal of his assignment, swiftly gaining ground.

Four hundred feet above the ground, the treetops didn’t look like velvet anymore. Their limbs and trunks were clearly solid objects that could flay the skin from Bolan’s body, crush his bones, drive shattered ribs into his heart and lungs. Or, he might escape injury while fouling his chute on the upper branches of a looming giant, dangling a hundred feet or more above the jungle floor.

Best to avoid the trees entirely, if he could, and drop into a clearing when he found one. If he found one.

While Bolan looked for an LZ, he also watched for people on the ground below him. Beating radar scanners with his HALO drop didn’t mean he was free and clear, if someone saw him falling from the sky and passed word on to the army or MOPOL, the mobile police branch of Nigeria’s national police force.

Bolan wouldn’t fire on police—a self-imposed restriction he’d adopted at the onset of his one-man war against the Mafia a lifetime earlier—and he hadn’t dropped in from the blue to play tag in the jungle with a troop of soldiers who’d be pleased to shoot first and ask questions later, if at all.

Better by far if he was left alone to go about his business unobstructed.

Bolan saw a clearing up ahead, two hundred yards and closing. He adjusted his direction and descent accordingly, hung on and watched the mossy earth come up to meet him in a rush.

GRIMALDI DIDN’T like the plan, but, hey, what else was new? Each time he ferried Bolan to another drop zone, he experienced the fear that this might be their last time out together, that he’d never see the warrior’s solemn face again.

And that he’d be to blame.

Not in the sense of taking out his oldest living friend, but rather serving Bolan up to those who would annihilate him without thinking twice. A kind of Meals on Wings for cannibals.

That was ridiculous, of course. Grimaldi knew it with the portion of his mind that processed rational, sequential thoughts. But knowing and believing were sometimes very different things.

Granted, he could have begged off, passed the job to someone else, but what would that accomplish? Nothing beyond handing Bolan to a stranger who would get him to the slaughterhouse on time, without a fare-thee-well. At least Grimaldi understood what had been asked of Bolan, every time his friend took on another mission that could be his last.

The morbid turn of thought left the ace pilot disgusted with himself. He tried to shake it off, whistled a snatch of something tuneless for a moment, then gave up on that and watched the Gulf of Guinea passing underneath him. Were the people in the boats craning their necks, tracking his engine sounds and following his progress overhead? Was one of them, perhaps, a watcher who had seen the Beechcraft earlier, reported it to other watchers on dry land, and now logged his return?

It was a possibility, of course, but there was nothing he could do about it. Radar would have marked his plane’s arrival in Nigerian airspace and tracked him to the inland point where he had turned. The natural assumption would be that he’d dropped something or someone; the mystery only began there.

Or, at least, so he was hoping.

Nigeria imported and exported drugs. According to reports Grimaldi had seen from the Nigerian Drug Law Enforcement Agency, Colombian cocaine and heroin from Afghanistan came in via South Africa, while home-grown marijuana was exported by the ton. Police, as usual, bagged ten percent or more of the illicit cargoes flowing back and forth across their borders, when they weren’t hired to protect the shipments.

So, they might think he had dropped a load of drugs.

And then what?

It was sixty-forty that they’d order someone to investigate the theoretical drop zone, which meant relaying orders from headquarters to some outpost in the field. Maybe the brass in Lagos would reach out to their subordinates in Warri, who in turn would form a squad to roll out, have a look around, then report on what they found.

Which should be nothing.

If they went looking for drugs, they’d check the area where Grimaldi had turned his plane, then backtrack for a while along his flight path, coming or going, to see if they’d missed anything. There were no drugs to find, so they’d go home empty-handed and pissed off at wasting their time.

But if they weren’t looking for drugs…

He knew the search might be conducted differently if the Nigerians went looking for intruders. Whether they were educated on HALO techniques or not, they had to know that men manipulating parachutes could travel farther than a bale of cargo dropping from the sky, and that the men, once having landed, wouldn’t wait around for searchers to locate them.

It would be a different game, then, with a different cast of players. MOPOL still might be involved, but it was also possible that Bolan could be up against the State Security Service, the Defense Intelligence Agency or the competing National Intelligence Agency. The SSS was Nigeria’s FBI, in effect, widely accused of domestic political repression, while the NIA was equivalent to America’s CIA, and the DIA handled military intelligence.

In the worst-case scenario, Grimaldi supposed that all three agencies might decide to investigate his drop-in, with MOPOL agents thrown in for variety. And how many hunters could Bolan evade before his luck ran out?

Grimaldi’s long experience with Bolan, starting as a kidnap “victim” and continuing thereafter as a friend and willing ally, had taught him not to underestimate the Executioner’s abilities. No matter what the odds arrayed against him, the Sarge had always managed to emerge victorious.

So far.

But he was only human, after all.

One hell of a human, for sure, but still human.

Grimaldi trusted Bolan to succeed, no matter the task he was assigned. But if he fell along the way, revenge was guaranteed.

The pilot swore it on his soul, whatever that was worth.

He didn’t know jackshit about Nigeria, beyond the obvious. It was a state in Africa, beset by poverty—yet oil rich—disease and chaos verging on the point of civil war, where he would stand out like a sore white thumb. But the official language was English, because of former colonial rule, so he wouldn’t be stranded completely.

And if Bolan didn’t make it out, Grimaldi would be going on a little hunting trip.

An African safari, right.

He owed the big guy that, at least.

And Jack Grimaldi always paid his debts.

TOUCHDOWN WAS better than Bolan had any right to expect after stepping out of an airplane and plummeting more than 24,000 feet to Earth. He bent his knees, tucked and rolled as they’d taught him at Green Beret jump school back in the old days, and came up with only a few minor bruises to show for the leap.

Only bruises so far.

Step two was covering his tracks and getting out of there before some hypothetical pursuer caught his scent and turned his drop into a suicide mission.

Bolan took it step by step, with all due haste. He shed the parachute harness first thing, along with his combat webbing and weapons. Next, he stripped off the jumpsuit that had saved him from frostbite while soaring, but which now felt like a baked potato’s foil wrapper underneath the Nigerian sun. That done, he donned the combat rigging once again and went to work.

Fourth step, reel in the parachute and all its lines, compacting same into the smallest bundle he could reasonably manage. That done, he unsheathed his folding shovel and began to dig.

It didn’t have to be a deep grave, necessarily. Just deep enough to hide his jumpsuit, helmet, bottled oxygen and mask, the chute and rigging. If some kind of nylon-eating scavenger he’d never heard of came along and dug it up that night, so be it. Bolan would be long gone by that time, his mission either a success or a resounding, fatal failure.

More than depth, he would require concealment for the burial, in case someone came sniffing after him within the next few hours. To that end, he dug his dump pit in the shadow of a looming mahogany some thirty paces from the clearing where he’d landed, and spent precious time re-planting ferns he had disturbed during the excavation when he’d finished.

It wasn’t perfect—nothing man-made ever was—but it would do.

He had a four-mile hike ahead of him, through forest that had so far managed to escape the logger’s ax and chainsaw. As he understood it from background research, Nigeria, once in the heart of West Africa’s rain forest belt, had lost ninety-five percent of its native tree cover and now imported seventy-five percent of the lumber used in domestic construction. Some conservationists believed that there would be no forests left in the country by 2020, a decade and change down the road toward Doomsday.

That kind of slash-and-burn planning was seen throughout Africa, in agriculture, mineral prospecting, environmental protection, disease control—you name it. The native peoples once ruled and exploited by cruel foreign masters now seemed hell-bent on turning their ancestral homeland into a vision of post-apocalyptic hell, sacrificing Mother Nature on the twin altars of profit and national pride.