полная версия

полная версияThe Expositor's Bible: The Books of Chronicles

But the Christian Church is mistress of a more compelling magic than even Eastern patience and tenacity: out of the storms that threaten her, she draws new energies for service, and learns a more expressive language in which to declare the glory of God.

Let us glance for a moment at the meanings of the group of Divine names given above. We have said that, in addition to Melech in Malchi-, Abi, Ahi, and Ammi are to be regarded as Divine names. One reason for this is that their use as prefixes is strictly analogous to that of El and Jeho-. We have Abijah and Ahijah as well as Elijah, Abiel and Ammiel as well as Eliel, Abiram and Ahiram as well as Jehoram; Ammishaddai compares with Zurishaddai, and Ammizabad with Jehozabad, nor would it be difficult to add many other examples. If this view be correct, Ammi will have nothing to do with the Hebrew word for “people,” but will rather be connected with the corresponding Arabic word for “uncle.”55 As the use of such terms as “brother” and “uncle” for Divine names is not consonant with Hebrew theology in its historic period, the names which contain these prefixes must have come down from earlier ages, and were used in later times without any consciousness of their original sense. Probably they were explained by new etymologies more in harmony with the spirit of the times; compare the etymology “father of a multitude of nations” given to Abraham. Even Abi-, father, in the early times to which its use as a prefix must be referred, cannot have had the full spiritual meaning which now attaches to it as a Divine title. It probably only signified the ultimate source of life. The disappearance of these religious terms from the common vocabulary and their use in names long after their significance had been forgotten are ordinary phenomena in the development of language and religion. How many of the millions who use our English names for the days of the week ever give a thought to Thor or Freya? Such phenomena have more than an antiquarian interest. They remind us that religious terms, and phrases, and formulæ derive their influence and value from their adaptation to the age which accepts them; and therefore many of them will become unintelligible or even misleading to later generations. Language varies continuously, circumstances change, experience widens, and every age has a right to demand that Divine truth shall be presented in the words and metaphors that give it the clearest and most forcible expression. Many of the simple truths that are most essential to salvation admit of being stated once for all; but dogmatic theology fossilises fast, and the bread of one generation may become a stone to the next.

The history of these names illustrates yet another phenomenon. In some narrow and imperfect sense the early Semitic peoples seem to have called God “Father” and “Brother.” Because the terms were limited to a narrow sense, the Israelites grew to a level of religious truth at which they could no longer use them; but as they made yet further progress they came to know more of what was meant by fatherhood and brotherhood, and gained also a deeper knowledge of God. At length the Church resumed these ancient Semitic terms; and Christians call God “Abba, Father,” and speak of the Eternal Son as their elder Brother. And thus sometimes, but not always, an antique phrase may for a time seem unsuitable and misleading, and then again may prove to be the best expression for the newest and fullest truth. Our criticism of a religious formula may simply reveal our failure to grasp the wealth of meaning which its words and symbols can contain.

Turning from these obsolete names to those in common use —El; Jehovah; Shaddai; Zur; Melech– probably the prevailing idea popularly associated with them all was that of strength: El, strength in the abstract; Jehovah, strength shown in permanence and independence; Shaddai, the strength that causes terror, the Almighty from whom cometh destruction56; Zur, rock, the material symbol of strength, Melech, king, the possessor of authority. In early times the first and most essential attribute of Deity is power, but with this idea of strength a certain attribute of beneficence is soon associated. The strong God is the Ally of His people; His permanence is the guarantee of their national existence; He destroys their enemies. The rock is a place of refuge; and, again, Jehovah's people may rejoice in the shadow of a great rock in a weary land. The King leads them to battle, and gives them their enemies for a spoil.

We must not, however, suppose that pious Israelites would consciously and systematically discriminate between these names, any more than ordinary Christians do between God, Lord, Father, Christ, Saviour, Jesus. Their usage would be governed by changing currents of sentiment very difficult to understand and explain after the lapse of thousands of years. In the year a. d. 3000, for instance, it will be difficult for the historian of dogmatics to explain accurately why some nineteenth-century Christians preferred to speak of “dear Jesus” and others of “the Christ.”

But the simple Divine names reveal comparatively little; much more may be learnt from the numerous compounds they help to form. Some of the more curious have already been noticed, but the real significance of this nomenclature is to be looked for in the more ordinary and natural names. Here, as before, we can only select from the long and varied list. Let us take some of the favourite names and some of the roots most often used, almost always, be it remembered, in combination with Divine names. The different varieties of these sacred names rendered it possible to construct various personal names embodying the same idea. Also the same Divine name might be used either as prefix or affix. For instance, the idea that “God knows” is equally well expressed in the names Eliada (El-yada'), Jediael (Yada'-el), Jehoiada (Jeho-yada'), and Jedaiah (Yada'-yah). “God remembers” is expressed alike by Zachariah and Jozachar; “God hears” by Elishama (El-shama'), Samuel (if for Shama'-el), Ishmael (also from Shama'-el), Shemaiah, and Ishmaiah (both from Shama' and Yah); “God gives” by Elnathan, Nethaneel, Jonathan, and Nethaniah; “God helps” by Eliezer, Azareel, Joezer, and Azariah; “God is gracious” by Elhanan, Hananeel, Johanan, Hananiah, Baal-hanan, and, for a Carthaginian, Hannibal, giving us a curious connection between the Apostle of love, John (Johanan), and the deadly enemy of Rome.

The way in which the changes are rung upon these ideas shows how the ancient Israelites loved to dwell upon them. Nestle reckons that in the Old Testament sixty-one persons have names formed from the root nathan, to give; fifty-seven from shama, to hear; fifty-six from 'azar, to help; forty-five from hanan, to be gracious; forty-four from zakhar, to remember. Many persons, too, bear names from the root yada', to know. The favourite name is Zechariah, which is borne by twenty-five different persons.

Hence, according to the testimony of names, the Israelites' favourite ideas about God were that He heard, and knew, and remembered; that He was gracious, and helped men, and gave them gifts: but they loved best to think of Him as God the Giver. Their nomenclature recognises many other attributes, but these take the first place. The value of this testimony is enhanced by its utter unconsciousness and naturalness; it brings us nearer to the average man in his religious moments than any psalm or prophetic utterance. Men's chief interest in God was as the Giver. The idea has proved very permanent; St. James amplifies it: God is the Giver of every good and perfect gift. It lies latent in names: Theodosius, Theodore, Theodora, and Dorothea. The other favourite ideas are all related to this. God hears men's prayers, and knows their needs, and remembers them; He is gracious, and helps them by His gifts. Could anything be more pathetic than this artless self-revelation? Men's minds have little leisure for sin and salvation; they are kept down by the constant necessity of preserving and providing for a bare existence. Their cry to God is like the prayer of Jacob, “If Thou wilt give me bread to eat and raiment to put on!” The very confidence and gratitude that the names express imply periods of doubt and fear, when they said, “Can God prepare a table in the wilderness?” times when it seemed to them impossible that God could have heard their prayer or that He knew their misery, else why was there no deliverance? Had God forgotten to be gracious? Did He indeed remember? The names come to us as answers of faith to these suggestions of despair.

Possibly these old-world saints were not more preoccupied with their material needs than most modern Christians. Perhaps it is necessary to believe in a God who rules on earth before we can understand the Father who is in heaven. Does a man really trust in God for eternal life if he cannot trust Him for daily bread? But in any case these names provide us with very comprehensive formulæ, which we are at liberty to apply as freely as we please: the God who knows, and hears, and remembers, who is gracious, and helps men, and gives them gifts. To begin with, note how in a great array of Old Testament names God is the Subject, Actor, and Worker; the supreme facts of life are God and God's doings, not man and man's doings, what God is to man, not what man is to God. This is a foreshadowing of the Christian doctrines of grace and of the Divine sovereignty. And again we are left to fill in the objects of the sentences for ourselves: God hears, and remembers, and gives – what? All that we have to say to Him and all that we are capable of receiving from Him.

Chapter II. Heredity. 1 Chron. i. – ix

It has been said that Religion is the great discoverer of truth, while Science follows her slowly and after a long interval. Heredity, so much discussed just now, is sometimes treated as if its principles were a great discovery of the present century. Popular science is apt to ignore history and to mistake a fresh nomenclature for an entirely new system of truth, and yet the immense and far-reaching importance of heredity has been one of the commonplaces of thought ever since history began. Science has been anticipated, not merely by religious feeling, but by a universal instinct. In the old world political and social systems have been based upon the recognition of the principle of heredity, and religion has sanctioned such recognition. Caste in India is a religious even more than a social institution; and we use the term figuratively in reference to ancient and modern life, even when the institution has not formally existed. Without the aid of definite civil or religious law the force of sentiment and circumstances suffices to establish an informal system of caste. Thus the feudal aristocracy and guilds of the Middle Ages were not without their rough counterparts in the Old Testament. Moreover, the local divisions of the Hebrew kingdoms corresponded in theory, at any rate, to blood relationships; and the tribe, the clan, and the family had even more fixity and importance than now belong to the parish or the municipality. A man's family history or genealogy was the ruling factor in determining his home, his occupation, and his social position. In the chronicler's time this was especially the case with the official ministers of religion, the Temple establishment to which he himself belonged. The priests, the Levites, the singers, and doorkeepers formed castes in the strict sense of the word. A man's birth definitely assigned him to one of these classes, to which none but the members of certain families could belong.

But the genealogies had a deeper significance. Israel was Jehovah's chosen people, His son, to whom special privileges were guaranteed by solemn covenant. A man's claim to share in this covenant depended on his genuine Israelite descent, and the proof of such descent was an authentic genealogy. In these chapters the chronicler has taken infinite pains to collect pedigrees from all available sources and to construct a complete set of genealogies exhibiting the lines of descent of the families of Israel. His interest in this research was not merely antiquarian: he was investigating matters of the greatest social and religious importance to all the members of the Jewish community, and especially to his colleagues and friends in the Temple service. These chapters, which seem to us so dry and useless, were probably regarded by the chronicler's contemporaries as the most important part of his work. The preservation or discovery of a genealogy was almost a matter of life and death. Witness the episode in Ezra and Nehemiah57: “And of the priests: the children of Hobaiah, the children of Hakkoz, the children of Barzillai, which took a wife of the daughters of Barzillai the Gileadite, and was called after their name. These sought their register among those that were reckoned by genealogy, but it was not found; therefore they were deemed polluted and put from the priesthood. And the governor said unto them that they should not eat of the most holy things, till there stood up a priest with Urim and Thummim.” Cases like these would stimulate our author's enthusiasm. As he turned over dusty receptacles, and unrolled frayed parchments, and painfully deciphered crabbed and faded script, he would be excited by the hope of discovering some mislaid genealogy that would restore outcasts to their full status and privileges as Israelites and priests. Doubtless he had already acquired in some measure the subtle exegesis and minute casuistry that were the glory of later Rabbinism. Ingenious interpretation of obscure writing or the happy emendation of half-obliterated words might lend opportune aid in the recovery of a genealogy. On the other hand, there were vested interests ready to protest against the too easy acceptance of new claims. The priestly families of undoubted descent from Aaron would not thank a chronicler for reviving lapsed rights to a share in the offices and revenues of the Temple. This part of our author's task was as delicate as it was important.

We will now briefly consider the genealogies in these chapters in the order in which they are given. Chap. i. contains genealogies of the patriarchal period selected from Genesis. The existing races of the world are all traced back through Shem, Ham, and Japheth to Noah, and through him to Adam. The chronicler thus accepts and repeats the doctrine of Genesis that God made of one every nation of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth.58 All mankind, “Greek and Jew, circumcision and uncircumcision, barbarian, Scythian, bondman, freeman,”59 were alike descended from Noah, who was saved from the Flood by the special care of God; from Enoch, who walked with God; from Adam, who was created by God in His own image and likeness. The Israelites did not claim, like certain Greek clans, to be the descendants of a special god of their own, or, like the Athenians, to have sprung miraculously from sacred soil. Their genealogies testified that not merely Israelite nature, but human nature, is moulded on a Divine pattern. These apparently barren lists of names enshrine the great principles of the universal brotherhood of men and the universal Fatherhood of God. The chronicler wrote when the broad universalism of the prophets was being replaced by the hard exclusiveness of Judaism; and yet, perhaps unconsciously, he reproduces the genealogies which were to be one weapon of St. Paul in his struggle with that exclusiveness. The opening chapters of Genesis and Chronicles are among the foundations of the catholicity of the Church of Christ.

For the antediluvian period only the Sethite genealogy is given. The chronicler's object was simply to give the origin of existing races; and the descendants of Cain were omitted, as entirely destroyed by the Flood. Following the example of Genesis, the chronicler gives the genealogies of other races at the points at which they diverged from the ancestral line of Israel, and then continues the family history of the chosen race. In this way the descendants of Japheth and Ham, the non-Abrahamic Semites, the Ishmaelites, the sons of Keturah, and the Edomites are successively mentioned.

The relations of Israel with Edom were always close and mostly hostile. The Edomites had taken advantage of the overthrow of the southern kingdom to appropriate the south of Judah, and still continued to occupy it. The keen interest felt by the chronicler in Edom is shown by the large space devoted to the Edomites. The close contiguity of the Jews and Idumæans tended to promote mutual intercourse between them, and even threatened an eventual fusion of the two peoples. As a matter of fact, the Idumæan Herods became rulers of Judæa. To guard against such dangers to the separateness of the Jewish people, the chronicler emphasises the historical distinction of race between them and the Edomites.

From the beginning of the second chapter onwards the genealogies are wholly occupied with Israelites. The author's special interest in Judah is at once manifested. After giving the list of the twelve Patriarchs he devotes two and a half chapters to the families of Judah. Here again the materials have been mostly obtained from the earlier historical books. They are, however, combined with more recent traditions, so that in this chapter matter from different sources is pieced together in a very confusing fashion. One source of this confusion was the principle that the Jewish community could only consist of families of genuine Israelite descent. Now a large number of the returned exiles traced their descent to two brothers, Caleb and Jerahmeel; but in the older narratives Caleb and Jerahmeel are not Israelites. Caleb is a Kenizzite,60 and his descendants and those of Jerahmeel appear in close connection with the Kenites.61 Even in this chapter certain of the Calebites are called Kenites and connected in some strange way with the Rechabites.62 Though at the close of the monarchy the Calebites and Jerahmeelites had become an integral part of the tribe of Judah, their separate origin had not been forgotten, and Caleb and Jerahmeel had not been included in the Israelite genealogies. But after the Exile men came to feel more and more strongly that a common faith implied unity of race. Moreover, the practical unity of the Jews with these Kenizzites overbore the dim and fading memory of ancient tribal distinctions. Jews and Kenizzites had shared the Captivity, the Exile, and the Return; they worked, and fought, and worshipped side by side; and they were to all intents and purposes one nation, alike the people of Jehovah. This obvious and important practical truth was expressed as such truths were then wont to be expressed. The children of Caleb and Jerahmeel were finally and formally adopted into the chosen race. Caleb and Jerahmeel are no longer the sons of Jephunneh the Kenizzite; they are the sons of Hezron, the son of Perez, the son of Judah.63 A new genealogy was formed as a recognition rather than an explanation of accomplished facts.

Of the section containing the genealogies of Judah, the lion's share is naturally given to the house of David, to which a part of the second chapter and the whole of the third are devoted.

Next follow genealogies of the remaining tribes, those of Levi and Benjamin being by far the most complete. Chap. vi., which is devoted to Levi, affords evidence of the use by the chronicler of independent and sometimes inconsistent sources, and also illustrates his special interest in the priesthood and the Temple choir. A list of high-priests from Aaron to Ahimaaz is given twice over (vv. 4-8 and 49-53), but only one line of high-priests is recognised, the house of Zadok, whom Josiah's reforms had made the one priestly family in Israel. Their ancient rivals the high-priests of the house of Eli are as entirely ignored as the antediluvian Cainites. The existing high-priestly dynasty had been so long established that these other priests of Saul and David seemed no longer to have any significance for the religion of Israel.

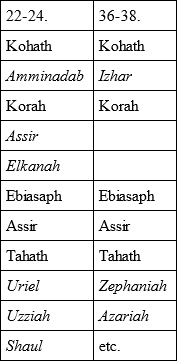

The pedigree of the three Levitical families of Gershom, Kohath, and Merari is also given twice over: in vv. 16-30 and 31-49. The former pedigree begins with the sons of Levi, and proceeds to their descendants; the latter begins with the founders of the guilds of singers, Heman, Asaph, and Ethan, and traces back their genealogies to Kohath, Gershom, and Merari respectively. But the pedigrees do not agree; compare, for instance, the lists of the Kohathites: —

We have here one of many illustrations of the fact that the chronicler used materials of very different value. To attempt to prove the absolute consistency of all his genealogies would be mere waste of time. It is by no means certain that he himself supposed them to be consistent. The frank juxtaposition of varying lists of ancestors rather suggests that he was prompted by a scholarly desire to preserve for his readers all available evidence of every kind.

In reading the genealogies of the tribe of Benjamin, it is specially interesting to find that in the Jewish community of the Restoration there were families tracing their descent through Mephibosheth and Jonathan to Saul.64 Apparently the chronicler and his contemporaries shared this special interest in the fortunes of a fallen dynasty, for the genealogy is given twice over. These circumstances are the more striking because in the actual history of Chronicles Saul is all but ignored.

The rest of the ninth chapter deals with the inhabitants of Jerusalem and the ministry of the Temple after the return from the Captivity, and is partly identical with sections of Ezra and Nehemiah. It closes the family history, as it were, of Israel, and its position indicates the standpoint and ruling interests of the chronicler.

Thus the nine opening chapters of genealogies and kindred matter strike the key-notes of the whole book. Some are personal and professional; some are religious. On the one hand, we have the origin of existing families and institutions; on the other hand, we have the election of the tribe of Judah and the house of David, of the tribe of Levi and the house of Aaron.

Let us consider first the hereditary character of the Jewish religion and priesthood. Here, as elsewhere, the formal doctrine only recognised and accepted actual facts. The conditions which received the sanction of religion were first imposed by the force of circumstances. In primitive times, if there was to be any religion at all, it had to be national; if God was to be worshipped at all, His worship was necessarily national, and He became in some measure a national God. Sympathies are limited by knowledge and by common interest. The ordinary Israelite knew very little of any other people than his own. There was little international comity in primitive times, and nations were slow to recognise that they had common interests. It was difficult for an Israelite to believe that his beloved Jehovah, in whom he had been taught to trust, was also the God of the Arabs and Syrians, who periodically raided his crops, and cattle, and slaves, and sometimes carried off his children, or of the Chaldæans, who made deliberate and complete arrangements for plundering the whole country, rasing its cities to the ground, and carrying away the population into distant exile. By a supreme act of faith, the prophets claimed the enemies and oppressors of Israel as instruments of the will of Jehovah, and the chronicler's genealogies show that he shared this faith; but it was still inevitable that the Jews should look out upon the world at large from the standpoint of their own national interests and experience. Jehovah was God of heaven and earth; but Israelites knew Him through the deliverance He had wrought for Israel, the punishments He had inflicted on her sins, and the messages He had entrusted to her prophets. As far as their knowledge and practical experience went, they knew Him as the God of Israel. The course of events since the fall of Samaria narrowed still further the local associations of Hebrew worship.