полная версия

полная версияHannibal

Exploring party.

When Cornelius got his men upon the land, they were too much exhausted by the sickness and misery they had endured upon the voyage to move on to meet Hannibal without some days for rest and refreshment. Cornelius, however, selected three hundred horsemen who were able to move, and sent them up the river on an exploring expedition, to learn the facts in respect to Hannibal, and to report them to him. Dispatching them accordingly, he remained himself in his camp, reorganizing and recruiting his army, and awaiting the return of the party that he had sent to explore.

Feelings of the Gauls in respect to Hannibal.

Although Hannibal had thus far met with no serious opposition in his progress through Gaul it must not, on that account, be supposed that the people, through whose territories he was passing, were really friendly to his cause, or pleased with his presence among them. An army is always a burden and a curse to any country that it enters, even when its only object is to pass peacefully through. The Gauls assumed a friendly attitude toward this dreaded invader and his horde only because they thought that by so doing he would the sooner pass and be gone. They were too weak, and had too few means of resistance to attempt to stop him; and, as the next best thing that they could do, resolved to render him every possible aid to hasten him on. This continued to be the policy of the various tribes until he reached the river. The people on the further side of the river, however, thought it was best for them to resist. They were nearer to the Roman territories, and, consequently, somewhat more under Roman influence. They feared the resentment of the Romans if they should, even passively, render any co-operation to Hannibal in his designs; and, as they had the broad and rapid river between them and their enemy, they thought there was a reasonable prospect that, with its aid, they could exclude him from their territories altogether.

The Gauls beyond the river oppose Hannibal's passage.

Thus it happened that, when Hannibal came to the stream, the people on one side were all eager to promote, while those on the other were determined to prevent his passage, both parties being animated by the same desire to free their country from such a pest as the presence of an army of ninety thousand men; so that Hannibal stood at last upon the banks of the river, with the people on his side of the stream waiting and ready to furnish all the boats and vessels that they could command, and to render every aid in their power in the embarkation, while those on the other were drawn up in battle array, rank behind rank, glittering with weapons, marshaled so as to guard every place of landing, and lining with pikes the whole extent of the shore, while the peaks of their tents, in vast numbers, with banners among them floating in the air, were to be seen in the distance behind them. All this time, the three hundred horsemen which Cornelius had dispatched were slowly and cautiously making their way up the river from the Roman encampment below.

Preparations for crossing the river.

Boat building.

After contemplating the scene presented to his view at the river for some time in silence, Hannibal commenced his preparations for crossing the stream. He collected first all the boats of every kind which could be obtained among the Gauls who lived along the bank of the river. These, however, only served for a beginning, and so he next got together all the workmen and all the tools which the country could furnish, for several miles around, and went to work constructing more. The Gauls of that region had a custom of making boats of the trunks of large trees. The tree, being felled and cut to the proper length, was hollowed out with hatchets and adzes, and then, being turned bottom upward, the outside was shaped in such a manner as to make it glide easily through the water. So convenient is this mode of making boats, that it is practiced, in cases where sufficiently large trees are found, to the present day. Such boats are now called canoes.

Rafts.

There were plenty of large trees on the banks of the Rhone. Hannibal's soldiers watched the Gauls at their work, in making boats of them, until they learned the art themselves. Some first assisted their new allies in the easier portions of the operation, and then began to fell large trees and make the boats themselves. Others, who had less skill or more impetuosity chose not to wait for the slow process of hollowing the wood, and they, accordingly, would fell the trees upon the shore, cut the trunks of equal lengths, place them side by side in the water, and bolt or bind them together so as to form a raft. The form and fashion of their craft was of no consequence, they said, as it was for one passage only. Any thing would answer, if it would only float and bear its burden over.

The enemy look on in silence.

In the mean time, the enemy upon the opposite shore looked on, but they could do nothing to impede these operations. If they had had artillery, such as is in use at the present day, they could have fired across the river, and have blown the boats and rafts to pieces with balls and shells as fast as the Gauls and Carthaginians could build them. In fact, the workmen could not have built them under such a cannonading; but the enemy, in this case, had nothing but spears, and arrows, and stones, to be thrown either by the hand, or by engines far too weak to send them with any effect across such a stream. They had to look on quietly, therefore, and allow these great and formidable preparations for an attack upon them to go on without interruption. Their only hope was to overwhelm the army with their missiles, and prevent their landing, when they should reach the bank at last in their attempt to cross the stream.

Difficulties of crossing a river.

If an army is crossing a river without any enemy to oppose them, a moderate number of boats will serve, as a part of the army can be transported at a time, and the whole gradually transferred from one bank to the other by repeated trips of the same conveyances. But when there is an enemy to encounter at the landing, it is necessary to provide the means of carrying over a very large force at a time; for if a small division were to go over first alone, it would only throw itself, weak and defenseless, into the hands of the enemy. Hannibal, therefore, waited until he had boats, rafts, and floats enough constructed to carry over a force all together sufficiently numerous and powerful to attack the enemy with a prospect of success.

Hannibal's tactics.

His stratagem.

The Romans, as we have already remarked, say that Hannibal was cunning. He certainly was not disposed, like Alexander, to trust in his battles to simple superiority of bravery and force, but was always contriving some stratagem to increase the chances of victory. He did so in this case. He kept up for many days a prodigious parade and bustle of building boats and rafts in sight of his enemy, as if his sole reliance was on the multitude of men that he could pour across the river at a single transportation, and he thus kept their attention closely riveted upon these preparations. All this time, however, he had another plan in course of execution. He had sent a strong body of troops secretly up the river, with orders to make their way stealthily through the forests, and cross the stream some few miles above. This force was intended to move back from the river, as soon as it should cross the stream, and come down upon the enemy in the rear, so as to attack and harass them there at the same time that Hannibal was crossing with the main body of the army. If they succeeded in crossing the river safely, they were to build a fire in the woods, on the other side, in order that the column of smoke which should ascend from it might serve as a signal of their success to Hannibal.

Detachment under Hanno.

Success of Hanno.

The signal.

This detachment was commanded by an officer named Hanno – of course a very different man from Hannibal's great enemy of that name in Carthage. Hanno set out in the night, moving back from the river, in commencing his march, so as to be entirely out of sight from the Gauls on the other side. He had some guides, belonging to the country, who promised to show him a convenient place for crossing. The party went up the river about twenty-five miles. Here they found a place where the water spread to a greater width, and where the current was less rapid, and the water not so deep. They got to this place in silence and secrecy, their enemies below not having suspected any such design. As they had, therefore, nobody to oppose them, they could cross much more easily than the main army below. They made some rafts for carrying over those of the men that could not swim, and such munitions of war as would be injured by the wet. The rest of the men waded till they reached the channel, and then swam, supporting themselves in part by their bucklers, which they placed beneath their bodies in the water. Thus they all crossed in safety. They paused a day, to dry their clothes and to rest, and then moved cautiously down the river until they were near enough to Hannibal's position to allow their signal to be seen. The fire was then built, and they gazed with exultation upon the column of smoke which ascended from it high into the air.

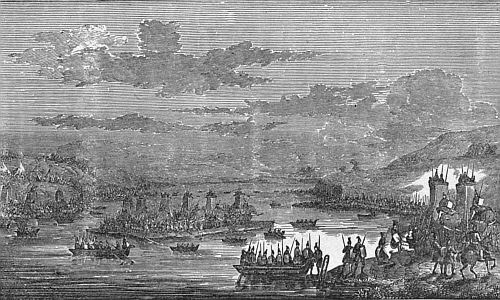

Passage of the river.

Hannibal saw the signal, and now immediately prepared to cross with his army. The horsemen embarked in boats, holding their horses by lines, with a view of leading them into the water so that they might swim in company with the boats. Other horses, bridled and accoutered, were put into large flat-bottomed boats, to be taken across dry, in order that they might be all ready for service at the instant of landing. The most vigorous and efficient portion of the army were, of course, selected for the first passage, while all those who, for any cause, were weak or disabled, remained behind, with the stores and munitions of war, to be transported afterward, when the first passage should have been effected. All this time the enemy, on the opposite shore, were getting their ranks in array, and making every thing ready for a furious assault upon the invaders the moment they should approach the land.

Scene of confusion.

Attack of Hanno.

Flight of the Gauls.

There was something like silence and order during the period while the men were embarking and pushing out from the land, but as they advanced into the current, the loud commands, and shouts, and outcries increased more and more, and the rapidity of the current and of the eddies by which the boats and rafts were hurried down the stream, or whirled against each other, soon produced a terrific scene of tumult and confusion. As soon as the first boats approached the land, the Gauls assembled to oppose them rushed down upon them with showers of missiles, and with those unearthly yells which barbarous warriors always raise in going into battle, as a means both of exciting themselves and of terrifying their enemy. Hannibal's officers urged the boats on, and endeavored, with as much coolness and deliberation as possible, to effect a landing. It is perhaps doubtful how the contest would have ended, had it not been for the detachment under Hanno, which now came suddenly into action. While the Gauls were in the height of their excitement, in attempting to drive back the Carthaginians from the bank, they were thunderstruck at hearing the shouts and cries of an enemy behind them, and, on looking around, they saw the troops of Hanno pouring down upon them from the thickets with terrible impetuosity and force. It is very difficult for an army to fight both in front and in the rear at the same time. The Gauls, after a brief struggle, abandoned the attempt any longer to oppose Hannibal's landing. They fled down the river and back into the interior, leaving Hanno in secure possession of the bank while Hannibal and his forces came up at their leisure out of the water, finding friends instead of enemies to receive them.

Transportation of the elephants.

Manner of doing it.

The remainder of the army, together with the stores and munitions of war, were next to be transported, and this was accomplished with little difficulty now that there was no enemy to disturb their operations. There was one part of the force, however, which occasioned some trouble and delay. It was a body of elephants which formed a part of the army. How to get these unwieldy animals across so broad and rapid a river was a question of no little difficulty. There are various accounts of the manner in which Hannibal accomplished the object, from which it would seem that different methods were employed. One mode was as follows: the keeper of the elephants selected one more spirited and passionate in disposition than the rest, and contrived to teaze and torment him so as to make him angry. The elephant advanced toward his keeper with his trunk raised to take vengeance. The keeper fled; the elephant pursued him, the other elephants of the herd following, as is the habit of the animal on such occasions. The keeper ran into the water as if to elude his pursuer, while the elephant and a large part of the herd pressed on after him. The man swam into the channel, and the elephants, before they could check themselves, found that they were beyond their depth. Some swam on after the keeper, and crossed the river, where they were easily secured. Others, terrified, abandoned themselves to the current, and were floated down, struggling helplessly as they went, until at last they grounded upon shallows or points of land, whence they gained the shore again, some on one side of the stream and some on the other.

A new plan.

Huge rafts.

This plan was thus only partially successful, and Hannibal devised a more effectual method for the remainder of the troop. He built an immensely large raft, floated it up to the shore, fastened it there securely, and covered it with earth, turf, and bushes, so as to make it resemble a projection of the land. He then caused a second raft to be constructed of the same size, and this he brought up to the outer edge of the other, fastened it there by a temporary connection, and covered and concealed it as he had done the first. The first of these rafts extended two hundred feet from the shore, and was fifty feet broad. The other, that is, the outer one, was only a little smaller. The soldiers then contrived to allure and drive the elephants over these rafts to the outer one, the animals imagining that they had not left the land. The two rafts were then disconnected from each other, and the outer one began to move with its bulky passengers over the water, towed by a number of boats which had previously been attached to its outer edge.

The elephants got safely over.

As soon as the elephants perceived the motion, they were alarmed, and began immediately to look anxiously this way and that, and to crowd toward the edges of the raft which was conveying them away. They found themselves hemmed in by water on every side, and were terrified and thrown into confusion. Some were crowded off into the river, and were drifted down till they landed below. The rest soon became calm, and allowed themselves to be quietly ferried across the stream, when they found that all hope of escape and resistance were equally vain.

The Elephants crossing the Rhone.

The reconnoitering parties.

The detachments meet.

A battle ensues.

In the mean time, while these events were occurring, the troop of three hundred, which Scipio had sent up the river to see what tidings he could learn of the Carthaginians, were slowly making their way toward the point where Hannibal was crossing; and it happened that Hannibal had sent down a troop of five hundred, when he first reached the river, to see if they could learn any tidings of the Romans. Neither of the armies had any idea how near they were to the other. The two detachments met suddenly and unexpectedly on the way. They were sent to explore, and not to fight; but as they were nearly equally matched, each was ambitious of the glory of capturing the others and carrying them prisoners to their camp. They fought a long and bloody battle. A great number were killed, and in about the same proportion on either side. The Romans say they conquered. We do not know what the Carthaginians said, but as both parties retreated from the field and went back to their respective camps, it is safe to infer that neither could boast of a very decisive victory.

Chapter V.

Hannibal crosses the Alps

B.C. 217The Alps.

It is difficult for any one who has not actually seen such mountain scenery as is presented by the Alps, to form any clear conception of its magnificence and grandeur. Hannibal had never seen the Alps, but the world was filled then, as now, with their fame.

Their sublimity and grandeur.

Perpetual cold in the upper regions of the atmosphere.

Some of the leading features of sublimity and grandeur which these mountains exhibit, result mainly from the perpetual cold which reigns upon their summits. This is owing simply to their elevation. In every part of the earth, as we ascend from the surface of the ground into the atmosphere, it becomes, for some mysterious reason or other, more and more cold as we rise, so that over our heads, wherever we are, there reigns, at a distance of two or three miles above us, an intense and perpetual cold. This is true not only in cool and temperate latitudes, but also in the most torrid regions of the globe. If we were to ascend in a balloon at Borneo at midday, when the burning sun of the tropics was directly over our heads, to an elevation of five or six miles, we should find that although we had been moving nearer to the sun all the time, its rays would have lost, gradually, all their power. They would fall upon us as brightly as ever, but their heat would be gone. They would feel like moonbeams, and we should be surrounded with an atmosphere as frosty as that of the icebergs of the frigid zone.

It is from this region of perpetual cold that hail-stones descend upon us in the midst of summer, and snow is continually forming and falling there; but the light and fleecy flakes melt before they reach the earth, so that, while the hail has such solidity and momentum that it forces its way through, the snow dissolves, and falls upon us as a cool and refreshing rain. Rain cools the air around us and the ground, because it comes from cooler regions of the air above.

Now it happens that not only the summits, but extensive portions of the upper declivities of the Alps, rise into the region of perpetual winter. Of course, ice congeals continually there, and the snow which forms falls to the ground as snow, and accumulates in vast and permanent stores. The summit of Mount Blanc is covered with a bed of snow of enormous thickness, which is almost as much a permanent geological stratum of the mountain as the granite which lies beneath it.

Avalanches.

Their terrible force.

Of course, during the winter months, the whole country of the Alps, valley as well as hill, is covered with snow. In the spring the snow melts in the valleys and plains, and higher up it becomes damp and heavy with partial melting, and slides down the declivities in vast avalanches, which sometimes are of such enormous magnitude, and descend with such resistless force, as to bring down earth, rocks, and even the trees of the forest in their train. On the higher declivities, however, and over all the rounded summits, the snow still clings to its place, yielding but very little to the feeble beams of the sun, even in July.

The glaciers.

Motion of the ice.

There are vast ravines and valleys among the higher Alps where the snow accumulates, being driven into them by winds and storms in the winter, and sliding into them, in great avalanches, in the spring. These vast depositories of snow become changed into ice below the surface; for at the surface there is a continual melting, and the water, flowing down through the mass, freezes below. Thus there are valleys, or rather ravines, some of them two or three miles wide and ten or fifteen miles long, filled with ice, transparent, solid, and blue, hundreds of feet in depth. They are called glaciers. And what is most astonishing in respect to these icy accumulations is that, though the ice is perfectly compact and solid, the whole mass is found to be continually in a state of slow motion down the valley in which it lies, at the rate of about a foot in twenty-four hours. By standing upon the surface and listening attentively, we hear, from time to time, a grinding sound. The rocks which lie along the sides are pulverized, and are continually moving against each other and falling; and then, besides, which is a more direct and positive proof still of the motion of the mass, a mark may be set up upon the ice, as has been often done, and marks corresponding to it made upon the solid rocks on each side of the valley, and by this means the fact of the motion, and the exact rate of it, may be fully ascertained.

Crevices and chasms.

Thus these valleys are really and literally rivers of ice, rising among the summits of the mountains, and flowing, slowly it is true, but with a continuous and certain current, to a sort of mouth in some great and open valley below. Here the streams which have flowed over the surface above, and descended into the mass through countless crevices and chasms, into which the traveler looks down with terror, concentrate and issue from under the ice in a turbid torrent, which comes out from a vast archway made by the falling in of masses which the water has undermined. This lower end of the glacier sometimes presents a perpendicular wall hundreds of feet in height; sometimes it crowds down into the fertile valley, advancing in some unusually cold summer into the cultivated country, where, as it slowly moves on, it plows up the ground, carries away the orchards and fields, and even drives the inhabitants from the villages which it threatens. If the next summer proves warm, the terrible monster slowly draws back its frigid head, and the inhabitants return to the ground it reluctantly evacuates, and attempt to repair the damage it has done.

Situation of the Alps.

Roads over the Alps.

The Alps lie between France and Italy, and the great valleys and the ranges of mountain land lie in such a direction that they must be crossed in order to pass from one country to the other. These ranges are, however, not regular. They are traversed by innumerable chasms, fissures, and ravines; in some places they rise in vast rounded summits and swells, covered with fields of spotless snow; in others they tower in lofty, needle-like peaks, which even the chamois can not scale, and where scarcely a flake of snow can find a place of rest. Around and among these peaks and summits, and through these frightful defiles and chasms, the roads twist and turn, in a zigzag and constantly ascending course, creeping along the most frightful precipices, sometimes beneath them and sometimes on the brink, penetrating the darkest and gloomiest defiles, skirting the most impetuous and foaming torrents, and at last, perhaps, emerging upon the surface of a glacier, to be lost in interminable fields of ice and snow, where countless brooks run in glassy channels, and crevasses yawn, ready to take advantage of any slip which may enable them to take down the traveler into their bottomless abysses.

Sublime scenery.

Beauty of the Alpine scenery.

Picturesque scenery.

And yet, notwithstanding the awful desolation which reigns in the upper regions of the Alps, the lower valleys, through which the streams finally meander out into the open plains, and by which the traveler gains access to the sublimer scenes of the upper mountains, are inexpressibly verdant and beautiful. They are fertilized by the deposits of continual inundations in the early spring, and the sun beats down into them with a genial warmth in summer, which brings out millions of flowers, of the most beautiful forms and colors, and ripens rapidly the broadest and richest fields of grain. Cottages, of every picturesque and beautiful form, tenanted by the cultivators, the shepherds and the herdsmen, crown every little swell in the bottom of the valley, and cling to the declivities of the mountains which rise on either hand. Above them eternal forests of firs and pines wave, feathering over the steepest and most rocky slopes with their somber foliage. Still higher, gray precipices rise and spires and pinnacles, far grander and more picturesque, if not so symmetrically formed, than those constructed by man. Between these there is seen, here and there, in the background, vast towering masses of white and dazzling snow, which crown the summits of the loftier mountains beyond.

![Rollo's Philosophy. [Air]](/covers_200/36364270.jpg)