полная версия

полная версияEssays: Scientific, Political, and Speculative, Volume I

15

It is true that since this essay was written reasons have been given for concluding that comets consist of swarms of meteors enveloped in aeriform matter. Very possibly this is the constitution of the periodic comets which, approximating their orbits to the plane of the Solar System, form established parts of the System, and which, as will be hereafter indicated, have probably a quite different origin.

16

Though this rule fails at the periphery of the Solar System, yet it fails only where the axis of rotation, instead of being almost perpendicular to the orbit-plane, is very little inclined to it; and where, therefore, the forces tending to produce the congruity of motions were but little operative.

17

It is true that, as expressed by him, these propositions of Laplace are not all beyond dispute. An astronomer of the highest authority, who has favoured me with some criticisms on this essay, alleges that instead of a nebulous ring rupturing at one point, and collapsing into a single mass, "all probability would be in favour of its breaking up into many masses." This alternative result certainly seems the more likely. But granting that a nebulous ring would break up into many masses, it may still be contended that, since the chances are infinity to one against these being of equal sizes and equidistant, they could not remain evenly distributed round their orbit. This annular chain of gaseous masses would break up into groups of masses; these groups would eventually aggregate into larger groups; and the final result would be the formation of a single mass. I have put the question to an astronomer scarcely second in authority to the one above referred to, and he agrees that this would probably be the process.

18

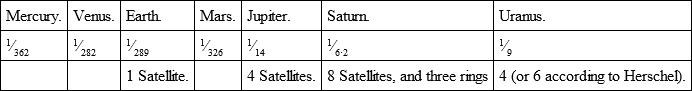

The comparative statement here given differs, slightly in most cases and in one case largely, from the statement included in this essay as originally published in 1858. As then given the table ran thus: —

The calculations ending with these figures were made while the Sun's distance was still estimated at 95 millions of miles. Of course the reduction afterwards established in the estimated distance, entailing, as it did, changes in the factors which entered into the calculations, affected the results; and, though it was unlikely that the relations stated would be materially changed, it was needful to have the calculations made afresh. Mr. Lynn has been good enough to undertake this task, and the figures given in the text are his. In the case of Mars a large error in my calculation had arisen from accepting Arago's statement of his density (0·95), which proves to be something like double what it should be. Here a curious incident may be named. When, in 1877, it was discovered that Mars has two satellites, though, according to my hypothesis, it seemed that he should have none, my faith in it received a shock; and since that time I have occasionally considered whether the fact is in any way reconcilable with the hypothesis. But now the proof afforded by Mr. Lynn that my calculation contained a wrong factor, disposes of the difficulty – nay, changes the objection to a verification. It turns out that, according to the hypothesis, Mars ought to have satellites; and, further, that he ought to have a number intermediate between 1 and 4.

19

Since this paragraph was first published, the discovery that Mars has two satellites revolving round him in periods shorter than that of his rotation, has shown that the implication on which Laplace here insists is general only, and not absolute. Were it a necessary assumption that all parts of a concentrating nebulous spheroid revolve with the same angular velocities, the exception would appear an inexplicable one; but if, as suggested in a preceding section, it is inferable from the process of formation of a nebulous spheroid, that its outer strata will move round the general axis with higher angular velocities than the inner ones, there follows a possible interpretation. Though, during the earlier stages of concentration, while the nebulous matter, and especially its peripheral portions, are very rare, the effects of fluid-friction will be too small to change greatly such differences of angular velocities as exist; yet, when concentration has reached its last stages, and the matter is passing from the gaseous into the liquid and solid states, and when also the convection-currents have become common to the whole mass (which they probably at first are not), the angular velocity of the peripheral portion will gradually be assimilated to that of the interior; and it becomes comprehensible that in the case of Mars the peripheral portion, more and more dragged back by the internal mass, lost part of its velocity during the interval between the formation of the innermost satellite and the arrival at the final form.

20

I was about to suppress part of the above paragraph, written before the science of solar physics had taken shape, because of certain physical difficulties which stand in the way of its argument, when, on looking into recent astronomical works, I found that the hypothesis it sets forth respecting the Sun's structure has kinships to the several hypotheses since set forth by Zöllner, Faye, and Young. I have therefore decided to let it stand as it originally did.

The contemplated partial suppression just named, was prompted by recognition of the truth that to effect mechanical stability the gaseous interior of the Sun must have a density at least equal to that of the molten shell (greater, indeed, at the centre); and this seems to imply a specific gravity higher than that which he possesses. It may, indeed, be that the unknown elements which spectrum analysis shows to exist in the Sun, are metals of very low specific gravities, and that, existing in large proportion with other of the lighter metals, they may form a molten shell not denser than is implied by the facts. But this can be regarded as nothing more than a possibility.

No need, however, has arisen for either relinquishing or holding but loosely the associated conclusions respecting the constitution of the photosphere and its envelope. Widely speculative as seemed these suggested corollaries from the Nebular Hypothesis when set forth in 1858, and quite at variance with the beliefs then current, they proved to be not ill-founded. At the close of 1859, there came the discoveries of Kirchhoff, proving the existence of various metallic vapours in the Sun's atmosphere.

21

Of course there remains the question whether, before the stage here recognized, there had already been produced a high temperature by those collisions of celestial masses which reduced the matter to a nebulous form. As suggested in First Principles (§ 136 in the edition of 1862, and § 182 in subsequent editions), there must, after there have been effected all those minor dissolutions which follow evolutions, remain to be effected the dissolutions of the great bodies in and on which the minor evolutions and dissolutions have taken place; and it was argued that such dissolutions will be, at some time or other, effected by those immense transformations of molar motion into molecular motion, consequent on collisions: the argument being based on the statement of Sir John Herschel, that in clusters of stars collisions must inevitably occur. It may, however, be objected that though such a result may be reasonably looked for in closely aggregated assemblages of stars, it is difficult to conceive of its taking place throughout our Sidereal System at large, the members of which, and their intervals, may be roughly figured as pins-heads 50 miles apart. It would seem that something like an eternity must elapse before, by ethereal resistance or other cause, these can be brought into proximity great enough to make collisions probable.

22

The two sentences which, in the text, precede the asterisk, I have introduced while these pages are standing in type: being led to do so by the perusal of some notes kindly lent to me by Prof. Dewar, containing the outline of a lecture he gave at the Royal Institution during the session of 1880. Discussing the conditions under which, if "our so-called elements are compounded of elemental matter", they may have been formed, Prof. Dewar, arguing from the known habitudes of compound substances, concludes that the formation is in each case a function of pressure, temperature, and nature of the environing gases.

23

At the date of this passage the established teleology made it seem needful to assume that all the planets are habitable, and that even beneath the photosphere of the Sun there exists a dark body which may be the scene of life; but since then, the influence of teleology has so far diminished that this hypothesis can no longer be called the current one.

24

It may here be mentioned (though the principal significance of this comes under the next head) that the average mean distance of the later-discovered planetoids is somewhat greater than that of these earlier-discovered; amounting to 2·61 for Nos. 1 to 35 and 2·80 for Nos. 211 to 245. For this observation I am indebted to Mr. Lynn; whose attention was drawn to it while revising for me the statements contained in this paragraph, so as to include discoveries made since the paragraph was written.

25

If the "rice-grain" appearance is thus produced by the tops of the ascending currents (and M. Faye accepts this interpretation), then I think it excludes M. Faye's hypothesis that the Sun is gaseous throughout. The comparative smallness of the light-giving spots and their comparative uniformity of size, show us that they have ascended through a stratum of but moderate depth (say 10,000 miles), and that this stratum has a definite lower limit. This favours the hypothesis of a molten shell.

26

I should add that while M. Faye ascribes solar spots to clouds formed within cyclones, we differ concerning the nature of the cloud. I have argued that it is formed by rarefaction, and consequent refrigeration, of the metallic gases constituting the stratum in which the cyclone exists. He argues that it is formed within the mass of cooled hydrogen drawn from the chromosphere into the vortex of the cyclone. Speaking of the cyclones he says: – "Dans leur embouchure évasée ils entraîneront l'hydrogène froid de la chromosphère, produisant partout sur leur trajet vertical un abaissement notable de température et une obscurité relative, due à l'opacité de l'hydrogène froid englouti." (Revue Scientifique, 24 March 1883.) Considering the intense cold required to reduce hydrogen to the "critical point," it is a strong supposition that the motion given to it by fluid friction on entering the vortex of the cyclone, can produce a rotation, rarefaction, and cooling, great enough to produce precipitation in a region so intensely heated.

27

Sir Charles Lyell is no longer to be classed among Uniformitarians. With rare and admirable candour he has, since this was written, yielded to the arguments of Mr. Darwin.

28

It may be well to warn the reader against an error fallen into by one who criticised this essay on its first publication – the error of supposing that the analogy here intended to be drawn, is a specific analogy between the organization of society in England, and the human organization. As said at the outset, no such specific analogy exists. The above parallel is one between the most-developed systems of governmental organization, individual and social; and the vertebrate type is instanced merely as exhibiting this most-developed system. If any specific comparison were made, which it cannot rationally be, it would be made with some much lower vertebrate form than the human.

29

A critical reader may raise an objection. If animal-worship is to be rationally interpreted, how can the interpretation set out by assuming a belief in the spirits of dead ancestors – a belief which just as much requires explanation? Doubtless there is here a wide gap in the argument. I hope eventually to fill it up. Here, out of many experiences which conspire to generate this belief, I can but briefly indicate the leading ones: 1. It is not impossible that his shadow, following him everywhere, and moving as he moves, may have some small share in giving to the savage a vague idea of his duality. It needs but to watch a child's interest in the movements of its shadow, and to remember that at first a shadow cannot be interpreted as a negation of light, but is looked upon as an entity, to perceive that the savage may very possibly consider it as a specific something which forms part of him. 2. A much more decided suggestion of the same kind is likely to result from the reflection of his face and figure in water: imitating him as it does in his form, colours, motions, grimaces. When we remember that not unfrequently a savage objects to have his portrait taken, because he thinks whoever carries away a representation of him carries away some part of his being, we see how probable it is that he thinks his double in the water is a reality in some way belonging to him. 3. Echoes must greatly tend to confirm the idea of duality otherwise arrived at. Incapable as he is of understanding their natural origin, the primitive man necessarily ascribes them to living beings – beings who mock him and elude his search. 4. The suggestions resulting from these and other physical phenomena are, however, secondary in importance. The root of this belief in another self lies in the experience of dreams. The distinction so easily made by us between our life in dreams and our real life, is one which the savage recognizes in but a vague way; and he cannot express even that distinction which he perceives. When he awakes, and to those who have seen him lying quietly asleep, describes where he has been, and what he has done, his rude language fails to state the difference between seeing and dreaming that he saw, doing and dreaming that he did. From this inadequacy of his language it not only results that he cannot truly represent this difference to others, but also that he cannot truly represent it to himself. Hence, in the absence of an alternative interpretation, his belief, and that of those to whom he tells his adventures, is that his other self has been away, and came back when he awoke. And this belief, which we find among various existing savage tribes, we equally find in the traditions of the early civilized races. 5. The conception of another self capable of going away and returning, receives what to the savage must seem conclusive verifications from the abnormal suspensions of consciousness, and derangements of consciousness, that occasionally occur in members of his tribe. One who has fainted, and cannot be immediately brought back to himself (note the significance of our own phrases "returning to himself," etc.) as a sleeper can, shows him a state in which the other self has been away for a time beyond recall. Still more is this prolonged absence of the other self shown him in cases of apoplexy, catalepsy, and other forms of suspended animation. Here for hours the other self persists in remaining away, and on returning refuses to say where he has been. Further verification is afforded by every epileptic subject, into whose body, during the absence of the other self, some enemy has entered; for how else does it happen that the other self, on returning, denies all knowledge of what his body has been doing? And this supposition that the body has been "possessed" by some other being, is confirmed by the phenomena of somnambulism and insanity. 6. What, then, is the interpretation inevitably put upon death? The other self has habitually returned after sleep, which simulates death. It has returned, too, after fainting, which simulates death much more. It has even returned after the rigid state of catalepsy, which simulates death very greatly. Will it not return also after this still more prolonged quiescence and rigidity? Clearly it is quite possible – quite probable even. The dead man's other self is gone away for a long time, but it still exists somewhere, far or near, and may at any moment come back to do all he said he would do. Hence the various burial-rites – the placing of weapons and valuables along with the body, the daily bringing of food to it, etc. I hope hereafter to show that, with such knowledge of the facts as he has, this interpretation is the most reasonable the savage can arrive at. Let me here, however, by way of showing how clearly the facts bear out this view, give one illustration out of many. "The ceremonies with which they [the Veddahs] invoke them [the shades of the dead] are few as they are simple. The most common is the following. An arrow is fixed upright in the ground, and the Veddah dances slowly round it, chanting this invocation, which is almost musical in its rhythm:"

"Mâ miya, mâ miy, mâ deyâ,Topang koyihetti mittigan yandâh?""My departed one, my departed one, my God!Where art thou wandering?""This invocation appears to be used on all occasions when the intervention of the guardian spirits is required, in sickness, preparatory to hunting, etc. Sometimes, in the latter case, a portion of the flesh of the game is promised as a votive offering, in the event of the chase being successful; and they believe that the spirits will appear to them in dreams and tell them where to hunt. Sometimes they cook food and place it in the dry bed of a river, or some other secluded spot, and then call on their deceased ancestors by name. 'Come and partake of this! Give us maintenance as you did when living! Come, wheresoever you may be; on a tree, on a rock, in the forest, come!' And they dance round the food, half chanting, half shouting, the invocation." – Bailey, in Transactions of the Ethnological Society, London, N. S., ii., p. 301-2.

30

Since the foregoing pages were written, my attention has been drawn by Sir John Lubbock to a passage in the appendix to the second edition of Prehistoric Times, in which he has indicated this derivation of tribal names. He says: "In endeavouring to account for the worship of animals, we must remember that names are very frequently taken from them. The children and followers of a man called the Bear or the Lion would make that a tribal name. Hence the animal itself would be first respected, at last worshipped." Of the genesis of this worship, however, Sir John Lubbock does not give any specific explanation. Apparently he inclines to the belief, tacitly adopted also by Mr. McLennan, that animal-worship is derived from an original Fetichism, of which it is a more developed form. As will shortly be seen, I take a different view of its origin.

31

Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, iii., p. 280-81.

32

I have since found, however, that the name Dawn, which occurs in various places, seems more frequently a birth-name, given because the birth took place at dawn.

33

See Prospective Review for January, 1852.

34

His criticism will be found in the National Review for January, 1856, under the title "Atheism."

35

Hereafter I hope to elucidate at length these phenomena of expression. For the present, I can refer only to such further indications as are contained in two essays on "The Physiology of Laughter" and "The Origin and Function of Music."

36

I may add that in Social Statics, chap. xxx., I have indicated, in a general way, the causes of the development of sympathy and the restraints upon its development – confining the discussion, however, to the case of the human race, my subject limiting me to that. The accompanying teleology I now disclaim.

37

Principles of Biology, §§ 159-168.

38

First Principles, second edition, § 97.

39

Principles of Psychology, second edition, vol. i., § 63.

40

Ibid., § 272.

41

It is probable that this shortening has resulted not directly but indirectly, from the selection of individuals which were noted for tenacity of hold; for the bull-dog's peculiarity in this respect seems due to relative shortness of the upper jaw, giving the underhung structure which, involving retreat of the nostrils, enables the dog to continue breathing while holding.

42

Though Mr. Darwin approved of this expression and occasionally employed it, he did not adopt it for general use; contending, very truly, that the expression Natural Selection is in some cases more convenient. See Animals and Plants under Domestication (first edition) Vol. i, p. 6; and Origin of Species (sixth edition) p. 49.

43

It is true that while not deliberately admitted by Mr. Darwin, these effects are not denied by him. In his Animals and Plants under Domestication (vol. ii, 281), he refers to certain chapters in the Principles of Biology, in which I have discussed this general inter-action of the medium and the organism, and ascribed certain most general traits to it. But though, by his expressions, he implies a sympathetic attention to the argument, he does not in such way adopt the conclusion as to assign to this factor any share in the genesis of organic structures – much less that large share which I believe it has had. I did not myself at that time, nor indeed until quite recently, see how extensive and profound have been the influences on organization which, as we shall presently see, are traceable to the early results of this fundamental relation between organism and medium. I may add that it is in an essay on "Transcendental Physiology," first published in 1857, that the line of thought here followed out in its wider bearings, was first entered upon.

44

Text-Book of Botany, &c. by Julius Sachs. Translated by A. W. Bennett and W. T. T. Dyer.

45

A Manual of the Infusoria, by W. Saville Kent. Vol. i, p. 232.

46

Ib. Vol. i, p. 241.

47

Kent, Vol. i, p. 56.

48

Ib. Vol. i, p. 57.

49

The Elements of Comparative Anatomy, by T. H. Huxley, pp. 7-9.

50

A Treatise on Comparative Embryology, by F. M. Balfour, Vol. ii, chap. xiii.

51

Sachs, p. 210.

52

Ibid. pp. 83-4.

53

Ibid. p. 185.

54

Ibid. 80.

55

Sachs, p. 83.

56

Ibid. p. 147.

57

A Treatise on Comparative Embryology. By Francis M. Balfour, LL.D., F.R.S. Vol. ii, p. 343 (second edition).

58

Balfour, l.c. Vol. ii, 400-1.

59

Balfour, l.c. Vol. ii, p. 401.

60

For a general delineation of the changes by which the development is effected, see Balfour, l.c. Vol. ii, pp. 401-4.

61

See Balfour, Vol. i, 149 and Vol. ii, 343-4.