полная версия

полная версияThe Life of John Marshall (Volume 2 of 4)

The Legislature promptly adopted them and would gladly have approved far stronger ones. "The leaders … were determined upon the overthrow of the General Government; and if no other measure would effect it, that they would risk it upon the chance of war… Some of them talked of 'seceding from the Union,'"899 Iredell writes his wife: "The General Assembly of Virginia are pursuing steps which directly lead to a civil war; but there is a respectable minority struggling in defense of the General Government, and the Government itself is fully prepared for anything they can do, resolved, if necessary, to meet force with force."900 Marshall declared that he "never saw such intemperance as existed in the V[irginia] Assembly."901

Following their defiant adoption of Madison's resolutions, the Republican majority of the Legislature issued a campaign pamphlet, also written by Madison,902 under the form of an address to the people. The "guardians of State Sovereignty would be perfidious if they did not warn" the people "of encroachments which … may" result in "usurped power"; the State Governments would be "precipitated into impotency and contempt" in case they yielded to such National laws as the Alien and Sedition Acts; if like "infractions of the Federal Compact" were repeated "until the people arose … in the majesty of their strength," it was certain that "the way for a revolution would be prepared."

The Federalist pleas "to disregard usurpation until foreign danger shall have passed" was "an artifice which may be forever used," because those who wished National power extended "can ever create national embarrassments to soothe the people to sleep whilst that power is swelling, silently, secretly and fatally."

Such was the Sedition Act which "commits the sacrilege of arresting reason; … punishes without trial; … bestows on the President despotic powers … which was never expected by the early friends of the Constitution." But now "Federal authority is deduced by implication" by which "the states will be stript of every right reserved." Such "tremendous pretensions … inflict a death wound on the Sovereignty of the States." Thus wrote the same Madison who had declared that nothing short of a veto by the National Government on "any and every act of the states" would suffice. There was, said Madison's campaign document, no "specified power" in the National Government "embracing a right against freedom of the press" – that was a "constitutional" prerogative of the States.

"Calumny" could be redressed in the State courts; but "usurpation can only be controuled by the act of society [revolution]." Here Madison quotes verbatim and in italics from Marshall's second letter to Talleyrand in defense of the liberty of the press, without, however, giving Marshall credit for the language or argument.903 Madison's argument is characteristically clear and compact, but abounds in striking phrases that suggest Jefferson.904

This "Address" of the Virginia Legislature was aimed primarily at Marshall, who was by far the most important Federalist candidate for Congress in the entire State. It was circulated at public expense and Marshall's friends could not possibly get his views before the people so authoritatively or so widely. But they did their best, for it was plain that Madison's Jeffersonized appeal, so uncharacteristic of that former Nationalist, must be answered. Marshall wrote the reply905 of the minority of the Legislature, who could not "remain silent under the unprecedented" attack of Madison. "Reluctantly," then, they "presented the present crisis plainly before" the people.

"For … national independence … the people of united America" changed a government by the British King for that of the Constitution. "The will of the majority produced, ratified, and conducts" this constitutional government. It was not perfect, of course; but "the best rule for freemen … in the opinion of our ancestors, was … that … of obedience to laws enacted by a majority of" the people's representatives.

Two other principles "promised immortality" to this fundamental idea: power of amendment and frequency of elections. "Under a Constitution thus formed, the prosperity of America" had become "great and unexampled." The people "bemoaned foreign war" when it "broke out"; but "they did not possess even a remote influence in its termination." The true American policy, therefore, was in the "avoiding of the existing carnage and the continuance of our existing happiness." It was for this reason that Washington, after considering everything, had proclaimed American Neutrality. Yet Genêt had "appealed" to the people "with acrimony" against the Government. This was resented "for a while only" and "the fire was rekindled as occasion afforded fuel."

Also, Great Britain's "unjustifiable conduct … rekindled our ardor for hostility and revenge." But Washington, averse to war, "made his last effort to avert its miseries." So came the Jay Treaty by which "peace was preserved with honor."

Marshall then reviews the outbursts against the Jay Treaty and their subsidence. France "taught by the bickerings of ourselves … reëchoed American reproaches with French views and French objects"; as a result "our commerce became a prey to French cruisers; our citizens were captured" and British outrages were repeated by the French, our "former friend … thereby committing suicide on our national and individual happiness."

Emulating Washington, Adams had twice striven for "honorable" adjustment. This was met by "an increase of insolence and affront." Thus America had "to choose between submission … and … independence. What American," asks Marshall, "could hesitate in the option?" And, "the choice being made, self-preservation commanded preparations for self-defense… – the fleet, … an army, a provision for the removal of dangerous aliens and the punishment of seditious citizens." Yet such measures "are charged with the atrocious design of creating a monarchy … and violating the constitution." Marshall argues that military preparation is our only security.

"Upon so solemn an occasion what curses would be adequate," asks Marshall, "to the supineness of our government, if militia were the only resort for safety, against the invasion of a veteran army, flushed with repeated victories, strong in the skill of its officers, and led by distinguished officers?" He then continues with the familiar arguments for military equipment.

Then comes his attack on the Virginia Resolutions. Had the criticisms of the Alien and Sedition Laws "been confined to ordinary peaceable and constitutional efforts to repeal them," no objection would have been made to such a course; but when "general hostility to our government" and "proceedings which may sap the foundations of our union" are resorted to, "duty" requires this appeal to the people.

Marshall next defends the constitutionality of these acts. "Powers necessary for the attainment of all objects which are general in their nature, which interest all America" and "can only be obtained by the coöperation of the whole … would be naturally vested in the government of the whole." It is obvious, he argues, that States must attend to local subjects and the Nation to general affairs.

The power to protect "the nation from the intrigues and conspiracies of dangerous aliens; … to secure the union from their wicked machinations, … which is essential to the common good," belongs to the National Government in the hands of which "is the force of the nation and the general power of protection from hostilities of every kind." Marshall then makes an extended argument in support of his Nationalist theory. Occasionally he employs almost the exact language which, years afterwards, appears in those constitutional opinions from the Supreme Bench that have given him his lasting fame. The doctrine of implied powers is expounded with all of his peculiar force and clearness, but with some overabundance of verbiage. In no writing or spoken word, before he became Chief Justice of the United States, did Marshall so extensively state his constitutional views as in this unknown paper.906

The House of Delegates, by a vote of 92 against 52,907 refused to publish the address of the minority along with that of the majority. Thereupon the Federalists printed and circulated it as a campaign document. It was so admired by the supporters of the Administration in Philadelphia that, according to the untrustworthy Callender, ten thousand copies were printed in the Capital and widely distributed.908

Marshall's authorship of this paper was not popularly known; and it produced little effect. Its tedious length, lighted only by occasional flashes of eloquence, invited Republican ridicule and derision. It contained, said Callender, "such quantities of words … that you turn absolutely tired"; it abounded in "barren tautology"; some sentences were nothing more than mere "assemblages of syllables"; and "the hypocritical canting that so strongly marks it corresponds very well with the dispatches of X. Y. and Z."909

Marshall's careful but over-elaborate paper was not, therefore, generally read. But the leading Federalists throughout the country were greatly pleased. The address was, said Sedgwick, "a masterly performance for which we are indebted to the pen of General Marshall, who has, by it, in some measure atoned for his pitiful electioneering epistle."910

When Murray, at The Hague, read the address, he concluded that Marshall was its author: "He may have been weak enough to declare against those laws that might be against the policy or necessity, etc., etc., etc., yet sustain their constitutionality… I hope J. Marshall did write the Address."911

The Republican appeal, unlike that of Marshall, was brief, simple, and replete with glowing catchwords that warmed the popular heart and fell easily from the lips of the multitude. And the Republican spirit was running high. The Virginia Legislature provided for an armory in Richmond to resist "encroachments" of the National Government.912 Memorials poured into the National Capital.913 By February "the tables of congress were loaded with petitions against" the unpopular Federalist legislation.914

Marshall's opinion of the motives of the Republican leaders, of the uncertainty of the campaign, of the real purpose of the Virginia Resolutions, is frankly set forth in his letter to Washington acknowledging the receipt of Judge Addison's charge: "No argument," wrote Marshall, "can moderate the leaders of the opposition… However I may regret the passage of one of the acts complained of [Sedition Law] I am firmly persuaded that the tempest has not been raised by them. Its cause lies much deeper and is not easily to be removed. Had they [Alien and Sedition Laws] never been passed, other measures would have been selected. An act operating on the press in any manner, affords to its opposers arguments which so captivate the public ear, which so mislead the public mind that the efforts of reason" are unavailing.

Marshall tells Washington that "the debates were long and animated" upon the Virginia Resolutions "which were substantiated by a majority of twenty-nine." He says that "sentiments were declared and … views were developed of a very serious and alarming extent… There are men who will hold power by any means rather than not hold it; and who would prefer a dissolution of the union to a continuance of an administration not of their own party. They will risk all ills … rather than permit that happiness which is dispensed by other hands than their own."

He is not sure, he says, of being elected; but adds, perhaps sarcastically, that "whatever the issue … may be I shall neither reproach myself, nor those at whose instance I have become a candidate, for the step I have taken. The exertions against me by" men in Virginia "and even from other states" are more "active and malignant than personal considerations would excite. If I fail," concludes Marshall, "I shall regret the failure more" because it will show "a temper hostile to our government … than of" his own "personal mortification."915

The Federalists were convinced that these extreme Republican tactics were the beginning of a serious effort to destroy the National Government. "The late attempt of Virginia and Kentucky," wrote Hamilton, "to unite the State Legislatures in a direct resistance to certain laws of the Union can be considered in no other light than as an attempt to change the government"; and he notes the "hostile declarations" of the Virginia Legislature; its "actual preparation of the means of supporting them by force"; its "measures to put their militia on a more efficient footing"; its "preparing considerable arsenals and magazines"; and its "laying new taxes on its citizens" for these purposes.916

To Sedgwick, Hamilton wrote of the "tendency of the doctrine advanced by Virginia and Kentucky to destroy the Constitution of the United States," and urged that the whole subject be referred to a special committee of Congress which should deal with the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions and justify the laws at which they were aimed. "No pains or expense," he insisted, "should be spared to disseminate this report… A little pamphlet containing it should find its way into every house in Virginia."917

Thus the congressional campaign of 1798-99 drew to a close. Marshall neglected none of those personal and familiar campaign devices which the American electorate of that time loved so well. His enemies declared that he carried these to the extreme; at a rally in Hanover County he "threw billets into the bonfires and danced around them with his constituents";918 he assured the voters that "his sentiments were the same as those of Mr. Clopton [the Republican candidate]"; he "spent several thousands of dollars upon barbecues."919

These charges of the besotted Callender,920 written from his cell in the jail at Richmond, are, of course, entirely untrue, except the story of dancing about the bonfire. Marshall's answers to "Freeholder" dispose of the second; his pressing need of money for the Fairfax purchase shows that he could have afforded no money for campaign purposes; and, indeed, this charge was so preposterous that even the reckless Callender concludes it to be unworthy of belief.

From the desperate nature of the struggle and the temper and political habit of the times, one might expect far harder things to have been said. Indeed, as the violence of the contest mounted to its climax, worse things were charged or intimated by word of mouth than were then put into type. Again it is the political hack, John Wood, who gives us a hint of the baseness of the slanders that were circulated; he describes a scandal in which Marshall and Pinckney were alleged to have been involved while in Paris, the unhappy fate of a woman, her desperate voyage to America, her persecution and sad ending.921

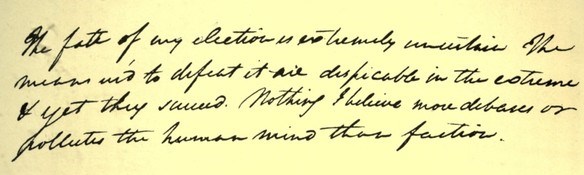

Marshall was profoundly disgusted by the methods employed to defeat him. Writing to his brother a short time before election day he briefly refers to the Republican assaults in stronger language than is to be found in any other letter ever written by him: —

"The fate of my election is extremely uncertain. The means us'd to defeat it are despicable in the extreme and yet they succeed. Nothing I believe more debases or pollutes the human mind than faction [party]."922

PART OF LETTER FROM JOHN MARSHALL TO HIS BROTHER, DATED APRIL 3, 1799

(Facsimile)

The Republicans everywhere grew more confident as the day of voting drew near. Neutrality, the Alien and Sedition Laws, the expense of the provisional army, the popular fear and hatred of a permanent military force, the high taxes, together with the reckless charges and slanders against the Federalists and the perfect discipline exacted of the Republicans by Jefferson – all were rapidly overcoming the patriotic fervor aroused by the X. Y. Z. disclosures. "The tide is evidently turning … from Marshall's romance" was the Republican commander's conclusion as the end of the campaign approached.923

For the first time Marshall's personal popularity was insufficient to assure victory. But the animosity of the Republicans caused them to make a false move which saved him at the very last. They circulated the report that Patrick Henry, the archenemy of "aristocrats," was against Marshall because the latter was one of this abhorred class. Marshall's friend, Archibald Blair, Clerk of the Executive Council, wrote Henry of this Republican campaign story.

Instantly both the fighter and the politician in Henry were roused; and the old warrior, from his retirement at Red Hill, wrote an extraordinary letter, full of affection for Marshall and burning with indignation at the Republican leaders. The Virginia Resolutions meant the "dissolution" of the Nation, wrote Henry; if that was not the purpose of the Republicans "they have none and act ex tempore." As to France, "her conduct has made it to the interest of the great family of mankind to wish the downfall of her present government." For the French Republic threatened to "destroy the great pillars of all government and social life – I mean virtue, morality, and religion," which "alone … is the armour … that renders us invincible." Also, said Henry, "infidelity, in its broad sense, under the name of philosophy, is fast spreading … under the patronage of French manners and principles."

Henry makes "these prefatory remarks" to "point out the kind of character amongst our countrymen most estimable in my [his] eyes." The ground thus prepared, Henry discharges all his guns against Marshall's enemies. "General Marshall and his colleagues exhibited the American character as respectable. France, in the period of her most triumphant fortune, beheld them as unappalled. Her threats left them as she found them…

"Can it be thought that with these sentiments I should utter anything tending to prejudice General Marshall's election? Very far from it indeed. Independently of the high gratification I felt from his public ministry, he ever stood high in my esteem as a private citizen. His temper and disposition were always pleasant, his talents and integrity unquestioned.

"These things are sufficient to place that gentleman far above any competitor in the district for congress. But when you add the particular information and insight which he has gained, and is able to communicate to our public councils, it is really astonishing, that even blindness itself should hesitate in the choice…

"Tell Marshall I love him, because he felt and acted as a republican, as an American. The story of the Scotch merchants and old torys voting for him is too stale, childish, and foolish, and is a French finesse; an appeal to prejudice, not reason and good sense… I really should give him my vote for Congress, preferably to any citizen in the state at this juncture, one only excepted [Washington]."924

Henry's letter saved Marshall. Not only was the congressional district full of Henry's political followers, but it contained large numbers of his close personal friends. His letter was passed from hand to hand among these and, by election day, was almost worn out by constant use.925

But the Federalist newspapers gave Henry no credit for turning the tide; according to these partisan sheets it was the "anarchistic" action of the Kentucky and Virginia Legislatures that elected Marshall. Quoting from a letter of Bushrod Washington, who had no more political acumen than a turtle, a Federalist newspaper declared: "We hear that General Marshall's election is placed beyond all doubt. I was firmly convinced that the violent measures of our Legislature (which were certainly intended to influence the election) would favor the pretensions of the Federal candidates by disclosing the views of the opposite party."926

Late in April the election was held. A witness of that event in Richmond tells of the incidents of the voting which were stirring even for that period of turbulent politics. A long, broad table or bench was placed on the Court-House Green, and upon it the local magistrates, acting as election judges, took their seats, their clerks before them. By the side of the judges sat the two candidates for Congress; and when an elector declared his preference for either, the favored one rose, bowing, and thanked his supporter.

Nobody but freeholders could then exercise the suffrage in Virginia.927 Any one owning one hundred acres of land or more in any county could vote, and this landowner could declare his choice in every county in which he possessed the necessary real estate. The voter did not cast a printed or written ballot, but merely stated, in the presence of the two candidates, the election officials, and the assembled gathering, the name of the candidate of his preference. There was no specified form for this announcement.928

"I vote for John Marshall."

"Thank you, sir," said the lank, easy-mannered Federalist candidate.

"Hurrah for Marshall!" shouted the compact band of Federalists.

"And I vote for Clopton," cried another freeholder.

"May you live a thousand years, my friend," said Marshall's competitor.

"Three cheers for Clopton!" roared the crowd of Republican enthusiasts.

Both Republican and Federalist leaders had seen to it that nothing was left undone which might bring victory to their respective candidates. The two political parties had been carefully "drilled to move together in a body." Each party had a business committee which attended to every practical detail of the election. Not a voter was overlooked. "Sick men were taken in their beds to the polls; the halt, the lame, and the blind were hunted up and every mode of conveyance was mustered into service." Time and again the vote was a tie. No sooner did one freeholder announce his preference for Marshall than another gave his suffrage to Clopton.

"A barrel of whisky with the head knocked in," free for everybody, stood beneath a tree; and "the majority took it straight," runs a narrative of a witness of the scene. So hot became the contest that fist-fights were frequent. During the afternoon, knock-down and drag-out affrays became so general that the county justices had hard work to quell the raging partisans. Throughout the day the shouting and huzzaing rose in volume as the whiskey sank in the barrel. At times the uproar was "perfectly deafening; men were shaking fists at each other, rolling up their sleeves, cursing and swearing… Some became wild with agitation." When a tie was broken by a new voter shouting that he was for Marshall or for Clopton, insults were hurled at his devoted head.

"You, sir, ought to have your mouth smashed," cried an enraged Republican when Thomas Rutherford voted for Marshall; and smashing of mouths, blacking of eyes, and breaking of heads there were in plenty. "The crowd rolled to and fro like a surging wave."929 Never before and seldom, if ever, since, in the history of Virginia, was any election so fiercely contested. When this "democratic" struggle was over, it was found that Marshall had been elected by the slender majority of 108.930

Washington was overjoyed at the Federalist success. He had ridden ten miles to vote for General Lee, who was elected;931 but he took a special delight in Marshall's victory. He hastened to write his political protégé: "With infinite pleasure I received the news of your Election. For the honor of the District I wish the majority had been greater; but let us be content, and hope, as the tide is turning, the current will soon run strong in your favor."932

Toward the end of the campaign, for the purpose of throwing into the contest Washington's personal influence, Marshall's enthusiastic friends had published the fact of Marshall's refusal to accept the various offices which had been tendered him by Washington. They had drawn a long bow, though very slightly, and stated positively that Marshall could have been Secretary of State.933 Marshall hastened to apologize: —

"Few of the unpleasant occurrences" of the campaign "have given me more real chagrin than this. To make a parade of proffered offices is a vanity which I trust I do not possess; but to boast of one never in my power would argue a littleness of mind at which I ought to blush." Marshall tells Washington that the person who published the report "never received it directly or indirectly from me." If he had known "that such a publication was designed" he "would certainly have suppressed it." It was inspired "unquestionably … by a wish to serve me," says Marshall, "and by resentment at the various malignant calumnies which have been so profusely bestowed on me."934