полная версия

полная версияEssays on Education and Kindred Subjects

Granting then, as we do, that formal exercises of the limbs are better than nothing – granting, further, that they may be used with advantage as supplementary aids; we yet contend that they can never serve in place of the exercises prompted by Nature. For girls, as well as boys, the sportive activities to which the instincts impel, are essential to bodily welfare. Whoever forbids them, forbids the divinely-appointed means to physical development.

A topic still remains – one perhaps more urgently demanding consideration than any of the foregoing. It is asserted by not a few, that among the educated classes the younger adults and those who are verging on maturity, are neither so well grown nor so strong as their seniors. On first hearing this assertion, we were inclined to class it as one of the many manifestations of the old tendency to exalt the past at the expense of the present. Calling to mind the facts that, as measured by ancient armour, modern men are proved to be larger than ancient men; and that the tables of mortality show no diminution, but rather an increase, in the duration of life, we paid little attention to what seemed a groundless belief. Detailed observation, however, has shaken our opinion. Omitting from the comparison the labouring classes, we have noticed a majority of cases in which the children do not reach the stature of their parents; and, in massiveness, making due allowance for difference of age, there seems a like inferiority. Medical men say that now-a-days people cannot bear nearly so much depletion as in times gone by. Premature baldness is far more common than it used to be. And an early decay of teeth occurs in the rising generation with startling frequency. In general vigour the contrast appears equally striking. Men of past generations, living riotously as they did, could bear more than men of the present generation, who live soberly, can bear. Though they drank hard, kept irregular hours, were regardless of fresh air, and thought little of cleanliness, our recent ancestors were capable of prolonged application without injury, even to a ripe old age: witness the annals of the bench and the bar. Yet we who think much about our bodily welfare; who eat with moderation, and do not drink to excess; who attend to ventilation, and use frequent ablutions; who make annual excursions, and have the benefit of greater medical knowledge; – we are continually breaking down under our work. Paying considerable attention to the laws of health, we seem to be weaker than our grandfathers who, in many respects, defied the laws of health. And, judging from the appearance and frequent ailments of the rising generation, they are likely to be even less robust than ourselves.

What is the meaning of this? Is it that past over-feeding, alike of adults and children, was less injurious than the under-feeding to which we have adverted as now so general? Is it that the deficient clothing which this delusive hardening-theory has encouraged, is to blame? Is it that the greater or less discouragement of juvenile sports, in deference to a false refinement is the cause? From our reasonings it may be inferred that each of these has probably had a share in producing the evil.9 But there has been yet another detrimental influence at work, perhaps more potent than any of the others: we mean – excess of mental application.

On old and young, the pressure of modern life puts a still-increasing strain. In all businesses and professions, intenser competition taxes the energies and abilities of every adult; and, to fit the young to hold their places under this intenser competition, they are subject to severer discipline than heretofore. The damage is thus doubled. Fathers, who find themselves run hard by their multiplying competitors, and, while labouring under this disadvantage, have to maintain a more expensive style of living, are all the year round obliged to work early and late, taking little exercise and getting but short holidays. The constitutions shaken by this continued over-application, they bequeath to their children. And then these comparatively feeble children, predisposed to break down even under ordinary strains on their energies, are required to go through a curriculum much more extended than that prescribed for the unenfeebled children of past generations.

The disastrous consequences that might be anticipated, are everywhere visible. Go where you will, and before long there come under your notice cases of children or youths, of either sex, more or less injured by undue study. Here, to recover from a state of debility thus produced, a year's rustication has been found necessary. There you find a chronic congestion of the brain, that has already lasted many months, and threatens to last much longer. Now you hear of a fever that resulted from the over-excitement in some way brought on at school. And again, the instance is that of a youth who has already had once to desist from his studies, and who, since his return to them, is frequently taken out of his class in a fainting fit. We state facts – facts not sought for, but which have been thrust on our observation during the last two years; and that, too, within a very limited range. Nor have we by any means exhausted the list. Quite recently we had the opportunity of marking how the evil becomes hereditary: the case being that of a lady of robust parentage, whose system was so injured by the régime of a Scotch boarding-school, where she was under-fed and over-worked, that she invariably suffers from vertigo on rising in the morning; and whose children, inheriting this enfeebled brain, are several of them unable to bear even a moderate amount of study without headache or giddiness. At the present time we have daily under our eyes, a young lady whose system has been damaged for life by the college-course through which she has passed. Taxed as she was to such an extent that she had no energy left for exercise, she is, now that she has finished her education, a constant complainant. Appetite small and very capricious, mostly refusing meat; extremities perpetually cold, even when the weather is warm; a feebleness which forbids anything but the slowest walking, and that only for a short time; palpitation on going upstairs; greatly impaired vision – these, joined with checked growth and lax tissue, are among the results entailed. And to her case we may add that of her friend and fellow-student; who is similarly weak; who is liable to faint even under the excitement of a quiet party of friends; and who has at length been obliged by her medical attendant to desist from study entirely.

If injuries so conspicuous are thus frequent, how very general must be the smaller, and inconspicuous injuries! To one case where positive illness is traceable to over-application, there are probably at least half-a-dozen cases where the evil is unobtrusive and slowly accumulating – cases where there is frequent derangement of the functions, attributed to this or that special cause, or to constitutional delicacy; cases where there is retardation and premature arrest of bodily growth; cases where a latent tendency to consumption is brought out and established; cases where a predisposition is given to that now common cerebral disorder brought on by the labour of adult life. How commonly health is thus undermined, will be clear to all who, after noting the frequent ailments of hard-worked professional and mercantile men, will reflect on the much worse effects which undue application must produce on the undeveloped systems of children. The young can bear neither so much hardship, nor so much physical exertion, nor so much mental exertion, as the full grown. Judge, then, if the full grown manifestly suffer from the excessive mental exertion required of them, how great must be the damage which a mental exertion, often equally excessive, inflicts on the young!

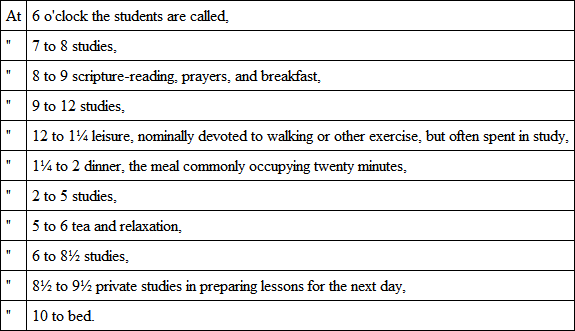

Indeed, when we examine the merciless school drill frequently enforced, the wonder is, not that it does extreme injury, but that it can be borne at all. Take the instance given by Sir John Forbes, from personal knowledge; and which he asserts, after much inquiry, to be an average sample of the middle-class girls'-school system throughout England. Omitting detailed divisions of time, we quote the summary of the twenty-four hours.

And what are the results of this "astounding regimen," as Sir John Forbes terms it? Of course feebleness, pallor, want of spirits, general ill-health. But he describes something more. This utter disregard of physical welfare, out of extreme anxiety to cultivate the mind – this prolonged exercise of brain and deficient exercise of limbs, – he found to be habitually followed, not only by disordered functions but by malformation. He says: – "We lately visited, in a large town, a boarding-school containing forty girls; and we learnt, on close and accurate inquiry, that there was not one of the girl who had been at the school two years (and the majority had been as long) that was not more or less crooked!"10

It may be that since 1833, when this was written, some improvement has taken place. We hope it has. But that the system is still common – nay, that it is in some cases carried to a greater extreme than ever; we can personally testify. We recently went over a training-college for young men: one of those instituted of late years for the purpose of supplying schools with well-disciplined teachers. Here, under official supervision, where something better than the judgment of private school-mistresses might have been looked for, we found the daily routine to be as follows: —

Thus, out of the twenty-four hours, eight are devoted to sleep; four and a quarter are occupied in dressing, prayers, meals, and the brief periods of rest accompanying them; ten and a half are given to study; and one and a quarter to exercise, which is optional and often avoided. Not only, however, are the ten-and-a-half hours of recognised study frequently increased to eleven-and-a-half by devoting to books the time set apart for exercise; but some of the students get up at four o'clock in the morning to prepare their lessons; and are actually encouraged by their teachers to do this! The course to be passed through in a given time is so extensive, and the teachers, whose credit is at stake in getting their pupils well through the examinations, are so urgent, that pupils are not uncommonly induced to spend twelve and thirteen hours a day in mental labour!

It needs no prophet to see that the bodily injury inflicted must be great. As we were told by one of the inmates, those who arrive with fresh complexions quickly become blanched. Illness is frequent: there are always some on the sick-list. Failure of appetite and indigestion are very common. Diarrhœa is a prevalent disorder: not uncommonly a third of the whole number of students suffering under it at the same time. Headache is generally complained of; and by some is borne almost daily for months. While a certain percentage break down entirely and go away.

That this should be the regimen of what is in some sort a model institution, established and superintended by the embodied enlightenment of the age, is a startling fact. That the severe examinations, joined with the short period assigned for preparation, should compel recourse to a system which inevitably undermines the health of all who pass through it, is proof, if not of cruelty, then of woeful ignorance.

The case is no doubt in a great degree exceptional – perhaps to be paralleled only in other institutions of the same class. But that cases so extreme should exist at all, goes far to show that the minds of the rising generation are greatly over-tasked. Expressing as they do the ideas of the educated community, the requirements of these training colleges, even in the absence of other evidence, would imply a prevailing tendency to an unduly urgent system of culture.

It seems strange that there should be so little consciousness of the dangers of over-education during youth, when there is so general a consciousness of the dangers of over-education during childhood. Most parents are partially aware of the evil consequences that follow infant-precocity. In every society may be heard reprobation of those who too early stimulate the minds of their little ones. And the dread of this early stimulation is great in proportion as there is adequate knowledge of the effects: witness the implied opinion of one of our most distinguished professors of physiology, who told us that he did not intend his little boy to learn any lessons until he was eight years old. But while to all it is a familiar truth that a forced development of intelligence in childhood, entails either physical feebleness, or ultimate stupidity, or early death; it appears not to be perceived that throughout youth the same truth holds. Yet it unquestionably does so. There is a given order in which, and a given rate at which, the faculties unfold. If the course of education conforms itself to that order and rate, well. If not – if the higher faculties are early taxed by presenting an order of knowledge more complex and abstract than can be readily assimilated; or if, by excess of culture, the intellect in general is developed to a degree beyond that which is natural to its age; the abnormal advantage gained will inevitably be accompanied by some equivalent, or more than equivalent, evil.

For Nature is a strict accountant; and if you demand of her in one direction more than she is prepared to lay out, she balances the account by making a deduction elsewhere. If you will let her follow her own course, taking care to supply, in right quantities and kinds, the raw materials of bodily and mental growth required at each age, she will eventually produce an individual more or less evenly developed. If, however, you insist on premature or undue growth of any one part, she will, with more or less protest, concede the point; but that she may do your extra work, she must leave some of her more important work undone. Let it never be forgotten that the amount of vital energy which the body at any moment possesses, is limited; and that, being limited, it is impossible to get from it more than a fixed quantity of results. In a child or youth the demands upon this vital energy are various and urgent. As before pointed out, the waste consequent on the day's bodily exercise has to be met; the wear of brain entailed by the day's study has to be made good; a certain additional growth of body has to be provided for; and also a certain additional growth of brain: to which must be added the amount of energy absorbed in digesting the large quantity of food required for meeting these many demands. Now, that to divert an excess of energy into any one of these channels is to abstract it from the others, is both manifest à priori, and proved à posteriori, by the experience of every one. Every one knows, for instance, that the digestion of a heavy meal makes such a demand on the system as to produce lassitude of mind and body, frequently ending in sleep. Every one knows, too, that excess of bodily exercise diminishes the power of thought – that the temporary prostration following any sudden exertion, or the fatigue produced by a thirty miles' walk, is accompanied by a disinclination to mental effort; that, after a month's pedestrian tour, the mental inertia is such that some days are required to overcome it; and that in peasants who spend their lives in muscular labour the activity of mind is very small. Again, it is a familiar truth that during those fits of rapid growth which sometimes occur in childhood, the great abstraction of energy is shown in an attendant prostration, bodily and mental. Once more, the facts that violent muscular exertion after eating, will stop digestion; and that children who are early put to hard labour become stunted; similarly exhibit the antagonism – similarly imply that excess of activity in one direction involves deficiency of it in other directions. Now, the law which is thus manifest in extreme cases, holds in all cases. These injurious abstractions of energy as certainly take place when the undue demands are slight and constant, as when they are great and sudden. Hence, if during youth the expenditure in mental labour exceeds that which Nature has provided for; the expenditure for other purposes falls below what it should have been; and evils of one kind or other are inevitably entailed. Let us briefly consider these evils.

Supposing the over-activity of brain to exceed the normal activity only in a moderate degree, there will be nothing more than some slight reaction on the development of the body: the stature falling a little below that which it would else have reached; or the bulk being less than it would have been; or the quality of tissue not being so good. One or more of these effects must necessarily occur. The extra quantity of blood supplied to the brain during mental exertion, and during the subsequent period in which the waste of cerebral substance is being made good, is blood that would else have been circulating through the limbs and viscera; and the growth or repair for which that blood would have supplied materials, is lost. The physical reaction being certain, the question is, whether the gain resulting from the extra culture is equivalent to the loss? – whether defect of bodily growth, or the want of that structural perfection which gives vigour and endurance, is compensated by the additional knowledge acquired?

When the excess of mental exertion is greater, there follow results far more serious; telling not only against bodily perfection, but against the perfection of the brain itself. It is a physiological law, first pointed out by M. Isidore St. Hilaire, and to which attention has been drawn by Mr. Lewes in his essay on "Dwarfs and Giants," that there is an antagonism between growth and development. By growth, as used in this antithetical sense, is to be understood increase of size; by development, increase of structure. And the law is, that great activity in either of these processes involves retardation or arrest of the other. A familiar example is furnished by the cases of the caterpillar and the chrysalis. In the caterpillar there is extremely rapid augmentation of bulk; but the structure is scarcely at all more complex when the caterpillar is full-grown than when it is small. In the chrysalis the bulk does not increase; on the contrary, weight is lost during this stage of the creature's life; but the elaboration of a more complex structure goes on with great activity. The antagonism, here so clear, is less traceable in higher creatures, because the two processes are carried on together. But we see it pretty well illustrated among ourselves when we contrast the sexes. A girl develops in body and mind rapidly, and ceases to grow comparatively early. A boy's bodily and mental development is slower, and his growth greater. At the age when the one is mature, finished, and having all faculties in full play, the other, whose vital energies have been more directed towards increase of size, is relatively incomplete in structure; and shows it in a comparative awkwardness, bodily and mental. Now this law is true of each separate part of the organism, as well as of the whole. The abnormally rapid advance of any organ in respect of structure, involves premature arrest of its growth; and this happens with the organ of the mind as certainly as with any other organ. The brain, which during early years is relatively large in mass but imperfect in structure, will, if required to perform its functions with undue activity, undergo a structural advance greater than is appropriate to its age; but the ultimate effect will be a falling short of the size and power that would else have been attained. And this is a part-cause – probably the chief cause – why precocious children, and youths who up to a certain time were carrying all before them, so often stop short and disappoint the high hopes of their parents.

But these results of over-education, disastrous as they are, are perhaps less disastrous than the effects produced on the health – the undermined constitution, the enfeebled energies, the morbid feelings. Recent discoveries in physiology have shown how immense is the influence of the brain over the functions of the body. Digestion, circulation, and through these all other organic processes, are profoundly affected by cerebral excitement. Whoever has seen repeated, as we have, the experiment first performed by Weber, showing the consequence of irritating the vagus nerve, which connects the brain with the viscera – whoever has seen the action of the heart suddenly arrested by irritating this nerve; slowly recommencing when the irritation is suspended; and again arrested the moment it is renewed; will have a vivid conception of the depressing influence which an over-wrought brain exercises on the body. The effects thus physiologically explained, are indeed exemplified in ordinary experience. There is no one but has felt the palpitation accompanying hope, fear, anger, joy – no one but has observed how laboured becomes the action of the heart when these feelings are violent. And though there are many who have never suffered that extreme emotional excitement which is followed by arrest of the heart's action and fainting; yet every one knows these to be cause and effect. It is a familiar fact, too, that disturbance of the stomach results from mental excitement exceeding a certain intensity. Loss of appetite is a common consequence alike of very pleasurable and very painful states of mind. When the event producing a pleasurable or painful state of mind occurs shortly after a meal, it not unfrequently happens either that the stomach rejects what has been eaten, or digests it with great difficulty and under protest. And as every one who taxes his brain much can testify, even purely intellectual action will, when excessive, produce analogous effects. Now the relation between brain and body which is so manifest in these extreme cases, holds equally in ordinary, less-marked cases. Just as these violent but temporary cerebral excitements produce violent but temporary disturbances of the viscera; so do the less violent but chronic cerebral excitements produce less violent but chronic visceral disturbances. This is not simply an inference: – it is a truth to which every medical man can bear witness; and it is one to which a long and sad experience enables us to give personal testimony. Various degrees and forms of bodily derangement, often taking years of enforced idleness to set partially right, result from this prolonged over-exertion of mind. Sometimes the heart is chiefly affected: habitual palpitations; a pulse much enfeebled; and very generally a diminution in the number of beats from seventy-two to sixty, or even fewer. Sometimes the conspicuous disorder is of the stomach: a dyspepsia which makes life a burden, and is amenable to no remedy but time. In many cases both heart and stomach are implicated. Mostly the sleep is short and broken. And very generally there is more or less mental depression.

Consider, then, how great must be the damage inflicted by undue mental excitement on children and youths. More or less of this constitutional disturbance will inevitably follow an exertion of brain beyond the normal amount; and when not so excessive as to produce absolute illness, is sure to entail a slowly accumulating degeneracy of physique. With a small and fastidious appetite, an imperfect digestion, and an enfeebled circulation, how can the developing body flourish? The due performance of every vital process depends on an adequate supply of good blood. Without enough good blood, no gland can secrete properly, no viscus can fully discharge its office. Without enough good blood, no nerve, muscle, membrane, or other tissue can be efficiently repaired. Without enough good blood, growth will neither be sound nor sufficient. Judge, then, how bad must be the consequences when to a growing body the weakened stomach supplies blood that is deficient in quantity and poor in quality; while the debilitated heart propels this poor and scanty blood with unnatural slowness.

And if, as all who investigate the matter must admit, physical degeneracy is a consequence of excessive study, how grave is the condemnation to be passed on this cramming-system above exemplified. It is a terrible mistake, from whatever point of view regarded. It is a mistake in so far as the mere acquirement of knowledge is concerned. For the mind, like the body, cannot assimilate beyond a certain rate; and if you ply it with facts faster than it can assimilate them, they are soon rejected again: instead of being built into the intellectual fabric, they fall out of recollection after the passing of the examination for which they were got up. It is a mistake, too, because it tends to make study distasteful. Either through the painful associations produced by ceaseless mental toil, or through the abnormal state of brain it leaves behind, it often generates an aversion to books; and, instead of that subsequent self-culture induced by rational education, there comes continued retrogression. It is a mistake, also, inasmuch as it assumes that the acquisition of knowledge is everything; and forgets that a much more important thing is the organisation of knowledge, for which time and spontaneous thinking are requisite. As Humboldt remarks respecting the progress of intelligence in general, that "the interpretation of Nature is obscured when the description languishes under too great an accumulation of insulated facts;" so, it may be remarked respecting the progress of individual intelligence, that the mind is over-burdened and hampered by an excess of ill-digested information. It is not the knowledge stored up as intellectual fat which is of value; but that which is turned into intellectual muscle. The mistake goes still deeper however. Even were the system good as producing intellectual efficiency, which it is not, it would still be bad, because, as we have shown, it is fatal to that vigour of physique needful to make intellectual training available in the struggle of life. Those who, in eagerness to cultivate their pupils' minds, are reckless of their bodies, do not remember that success in the world depends more on energy than on information; and that a policy which in cramming with information undermines energy, is self-defeating. The strong will and untiring activity due to abundant animal vigour, go far to compensate even great defects of education; and when joined with that quite adequate education which may be obtained without sacrificing health, they ensure an easy victory over competitors enfeebled by excessive study: prodigies of learning though they may be. A comparatively small and ill-made engine, worked at high pressure, will do more than a large and well-finished one worked at low-pressure. What folly is it, then, while finishing the engine, so to damage the boiler that it will not generate steam! Once more, the system is a mistake, as involving a false estimate of welfare in life. Even supposing it were a means to worldly success, instead of a means to worldly failure, yet, in the entailed ill-health, it would inflict a more than equivalent curse. What boots it to have attained wealth, if the wealth is accompanied by ceaseless ailments? What is the worth of distinction, if it has brought hypochondria with it? Surely no one needs telling that a good digestion, a bounding pulse, and high spirits, are elements of happiness which no external advantages can out-balance. Chronic bodily disorder casts a gloom over the brightest prospects; while the vivacity of strong health gilds even misfortune. We contend, then, that this over-education is vicious in every way – vicious, as giving knowledge that will soon be forgotten; vicious, as producing a disgust for knowledge; vicious, as neglecting that organisation of knowledge which is more important than its acquisition; vicious, as weakening or destroying that energy without which a trained intellect is useless; vicious, as entailing that ill-health for which even success would not compensate, and which makes failure doubly bitter. On women the effects of this forcing system are, if possible, even more injurious than on men. Being in great measure debarred from those vigorous and enjoyable exercises of body by which boys mitigate the evils of excessive study, girls feel these evils in their full intensity. Hence, the much smaller proportion of them who grow up well-made and healthy. In the pale, angular, flat-chested young ladies, so abundant in London drawing-rooms, we see the effect of merciless application, unrelieved by youthful sports; and this physical degeneracy hinders their welfare far more than their many accomplishments aid it. Mammas anxious to make their daughters attractive, could scarcely choose a course more fatal than this, which sacrifices the body to the mind. Either they disregard the tastes of the opposite sex, or else their conception of those tastes is erroneous. Men care little for erudition in women; but very much for physical beauty, good nature, and sound sense. How many conquests does the blue-stocking make through her extensive knowledge of history? What man ever fell in love with a woman because she understood Italian? Where is the Edwin who was brought to Angelina's feet by her German? But rosy cheeks and laughing eyes are great attractions. A finely rounded figure draws admiring glances. The liveliness and good humour that overflowing health produces, go a great way towards establishing attachments. Every one knows cases where bodily perfections, in the absence of all other recommendations, have incited a passion that carried all before it; but scarcely any one can point to a case where intellectual acquirements, apart from moral or physical attributes, have aroused such a feeling. The truth is that, out of the many elements uniting in various proportions to produce in a man's breast the complex emotion we call love, the strongest are those produced by physical attractions; the next in order of strength are those produced by moral attractions; the weakest are those produced by intellectual attractions; and even these are dependent less on acquired knowledge than on natural faculty – quickness, wit, insight. If any think the assertion a derogatory one, and inveigh against the masculine character for being thus swayed; we reply that they little know what they say when they thus call in question the Divine ordinations. Even were there no obvious meaning in the arrangement, we might be sure that some important end was subserved. But the meaning is quite obvious to those who examine. When we remember that one of Nature's ends, or rather her supreme end, is the welfare of posterity; further that, in so far as posterity are concerned, a cultivated intelligence based on a bad physique is of little worth, since its descendants will die out in a generation or two; and conversely that a good physique, however poor the accompanying mental endowments, is worth preserving, because, throughout future generations, the mental endowments may be indefinitely developed; we perceive how important is the balance of instincts above described. But, advantage apart, the instincts being thus balanced, it is folly to persist in a system which undermines a girl's constitution that it may overload her memory. Educate as highly as possible – the higher the better – providing no bodily injury is entailed (and we may remark, in passing, that a sufficiently high standard might be reached were the parrot-faculty cultivated less, and the human faculty more, and were the discipline extended over that now wasted period between leaving school and being married). But to educate in such manner, or to such extent, as to produce physical degeneracy, is to defeat the chief end for which the toil and cost and anxiety are submitted to. By subjecting their daughters to this high-pressure system, parents frequently ruin their prospects in life. Besides inflicting on them enfeebled health, with all its pains and disabilities and gloom; they not unfrequently doom them to celibacy.