полная версия

полная версияStudies in the Theory of Descent, Volume I

Temperature 0°-1° R. most of the time, but varying somewhat as the ice melted. (Both in 1878 and 1879 Mr. Edwards watched the box himself, and endeavoured to keep a low temperature.)

Of the 69 chrysalides not exposed to cold, 34 gave butterflies at from eleven to fourteen days after pupation, and 1 additional male emerged 11th August, or twenty-two days at least past the regular period of the species.

Of the iced chrysalides, from lot No. 1 emerged 4 females at eight days and a half to nine days and a half after removal from the ice, and 5 are now alive (Nov. 18) and will go over the winter.

From lot No. 2 emerged 1 male and 5 females at eight to nine days; another male came out at forty days; and 5 will hibernate.

From lot No. 3 emerged 4 females at nine to twelve days; another male came out at fifty-four days; and 6 were found to be dead.

In this experiment the author wished to see as exactly as possible – First, in what points changes would occur. Second, if there would be any change in the shape of the wings, as well as in markings or coloration – that is, whether the shape might remain as that of Marcellus, while the markings might be of Telamonides or Walshii; a summer form with winter markings. Third, to ascertain more closely than had yet been done what length of exposure was required to bring about a decided change, and what would be the effect of prolonging this period. After the experiments with Phyciodes Tharos, which had resulted in a suffusion of colour, the author hoped that some similar cases might be seen in Ajax. The decided changes in 1878 had been produced by eleven and sixteen days’ cold. In 1877, an exposure of two days and three-quarters to eight days had failed to produce an effect.

From these chrysalides 11 perfect butterflies were obtained, 1 male and 10 females. Some emerged crippled, and these were rejected, as it was not possible to make out the markings satisfactorily.

From lot No. 1, fourteen days, came: —

1 female between Marcellus and Telamonides.

2 females, Marcellus.

These 2 Marcellus were pale coloured, the light parts a dirty white; the submarginal lunules on hind wings were only two in number and small; at the anal angle was one large and one small red spot; the frontal hairs were very short. The first, or intermediate female, was also pale black, but the light parts were more green and less sordid; there were 3 large lunules; the anal red spot was double and connected, as in Telamonides; the frontal hairs short, as in Marcellus. These are the most salient points for comparing the several forms of Ajax. In nature, there is much difference in shape between Marcellus and Telamonides, still more between Marcellus and Walshii; and the latter may be distinguished from the other winter forms by the white tips of the tails. It is also smaller, and the anal spot is larger, with a broad white edging.

From lot No. 2, twenty days, came: —

1 female Marcellus, with single red spot.

1 female between Marcellus and Telamonides; general coloration pale; the lunules all obsolescent; 2 large red anal spots not connected; frontal hairs medium length, as in Telamonides.

1 female between Marcellus and Telamonides; colour bright and clear; 3 lunules; 2 large red spots; frontal hairs short.

1 female Telamonides; colours black and green; 4 lunules; a large double and connected red spot; frontal hairs medium.

2 female Telamonides; colours like last; 3 and 4 lunules; 2 large red spots; frontal hairs medium.

From lot No. 3, twenty-five days, came: —

1 male Telamonides; clear colours; 4 large lunules; 1 large, 1 small red spot; frontal hairs long.

1 female Telamonides; medium colours; 4 lunules; large double connected red spot; frontal hairs long.

In general shape all were Marcellus, the wings produced, the tails long.

From this it appeared that those exposed twenty-five days were fully changed; of those exposed twenty days, 3 were fully, 2 partly, 1 not at all; and of those exposed fourteen days, 1 partly, 2 not at all.

The butterflies from this lot of 104 chrysalides, but which had not been iced, were put in papers. Taking 6 males and 6 females from the papers just as they came to hand, Mr. Edwards set them, and compared them with the iced examples.

Of the 6 males, 4 had 1 red anal spot only, 2 had 1 large 1 small; 4 had 2 green lunules on the hind wings, 2 had 3, and in these last there was a 4th obsolescent, at outer angle; all had short frontal hairs.

Of the 6 females, 5 had but 1 red spot, 1 had 1 large 1 small spot; 5 had 2 lunules only, 1 had 3; all had short frontal hairs.

Comparing 6 of the females from the iced chrysalides, being those in which a change had more or less occurred, with the 6 females not iced:

1. All the former had the colours more intense, the black deeper, the light, green.

2. In 5 of the former the green lunules on hind wings were decidedly larger; 3 of the 6 had 4 distinct lunules, 1 had 3, 1 had 3, and a 4th obsolescent. Of the 6 females not iced none had 4, 2 had 2, and a 3rd, the lowest of the row, obsolescent; 3 had 3, the lowest being very small; one had 3, and a 4th, at outer angle, obsolescent.

3. In all the former the subapical spot on fore wing and the stripe on same wing which crosses the cell inside the common black band, were distinct and green; in all the latter these marks were either obscure or obsolescent.

4. In 4 of the former there was a large double connected red spot, and in one of the 4 it was edged with white on its upper side; 2 had 1 large and 1 small red spot. Of the latter 5 had 1 spot only, and the 6th had 1 spot and a red dot.

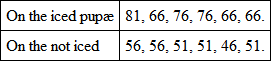

5. The former had all the black portions of the wing of deeper colour but less diffused, the bands being narrower; on the other hand, the green bands were wider as well as deeper coloured. Measuring the width of the outermost common green band along the middle of the upper medium interspace on fore wing in tenths of a millimetre, it was found to be as follows:

Measuring the common black discal band across the middle of the lower medium interspace on fore wing:

In other words the natural examples were more melanic than the others.

No difference was found in the length of the tails or in the length and breadth of wings. In other words, the cold had not altered the shape of the wings.

Comparing 1 male iced with 6 males not iced:

1. The former had a large double connected red anal spot, edged with white scales at top. Of the 6 not iced, 3 had but 1 red spot, 2 had 1 large 1 small, 1 had 1 large and a red dot.

2. The former had 4 green lunules; of the latter 3 had 3, 3 had only 2.

3. The former had the subapical spot and stripe in the cells clear green; of the latter 1 had the same, 5 had these obscure or obsolescent.

4. The colours of the iced male were bright; of the others, 2 were the same, 4 had the black pale, the light sordid white or greenish-white.

Looking over all, male and female, of both lots, the large size of the green submarginal lunules on the fore wings in the iced examples was found to be conspicuous as compared with all those not iced, though this feature is included in the general widening of the green bands spoken of.

In all the experiments with Ajax, if any change at all has been produced by cold, it is seen in the enlarging or doubling of the red anal spot, and in the increased number of clear green lunules on the hind wings. Almost always the frontal hairs are lengthened and the colour of the wings deepened, and the extent of the black area is also diminished. All these changes are in the direction of Telamonides, or the winter form.

That the effect of cold is not simply to precipitate the appearance of the winter form, causing the butterfly to emerge from the chrysalis in the summer in which it began its larval existence instead of the succeeding year, is evident from the fact that the butterflies come forth with the shape of Marcellus, although the markings may be of Telamonides or Walshii. And almost always some of the chrysalides, after having been iced, go over the winter, and then produce Telamonides, as do the hibernating pupæ in their natural state. The cold appears to have no effect on these individual chrysalides.59

With every experiment, however similar the conditions seem to be, and are intended to be, there is a difference in results; and further experiments – perhaps many – will be required before the cause of this is understood. For example, in 1878, the first butterfly emerged on the fourteenth day after removal from ice, the period being exactly what it is (at its longest) in the species in nature. Others emerged at 19–96 days. In 1879, the emergence began on the ninth day, and by the twelfth day all had come out, except three belated individuals, which came out at twenty, forty, and fifty-four days. In the last experiment, either the cold had not fully suspended the changes which the insect undergoes in the chrysalis, or its action was to hasten them after the chrysalides were taken from the ice. In the first experiment, apparently the changes were absolutely suspended as long as the cold remained.

It might be expected that the application of heat to the hibernating chrysalides would precipitate the appearance of the summer form, or change the markings of the butterfly into the summer form, even if the shape of the wings was not altered; that is, to produce individuals having the winter shape but the summer markings. But this was not found to occur. Mr. Edwards has been in the habit for several years of placing the chrysalides in a warm room, or in the greenhouse, early in the winter, thus causing the butterflies to emerge in February, instead of in March and April, as otherwise they would do. The heat in the house is 19° R. by day, and not less than 3.5° R. by night. But the winter form of the butterfly invariably emerged, usually Telamonides, occasionally Walshii.

Experiments with Phyciodes TharosExp. 1. – In July, 1875, eggs of P. Tharos were obtained on Aster Nova-Angliæ in the Catskill Mountains, and the young larvæ, when hatched, taken to Coalburgh, West Virginia. On the journey the larvæ were fed on various species of Aster, which they ate readily. By the 4th of September they had ceased feeding (after having twice moulted), and slept. Two weeks later part of them were again active, and fed for a day or two, when they gathered in clusters and moulted for the third time, then becoming lethargic, each one where it moulted with the cast skin by its side. The larvæ were then placed in a cellar, where they remained till February 7th, when those that were alive were transferred to the leaves of an Aster which had been forced in a greenhouse, and some commenced to feed the same day. In due time they moulted twice more, making, in some cases, a total of five moults. On May 5th the first larva pupated, and its butterfly emerged after thirteen days. Another emerged on the 30th, after eight days pupal period, this stage being shortened as the weather became warmer. There emerged altogether 8 butterflies, 5 males and 3 females, all of the form Marcia, and all of the variety designated C, except 1 female, which was var. B.60

Exp. 2. – On May 18th the first specimens (3 male Marcia) were seen on the wing at Coalburgh; 1 female was taken on the 19th, 2 on the 23rd, and 2 on the 24th, these being all that were seen up to that date, but shortly after both sexes became common. On the 26th, 7 females were captured and tied up in separate bags on branches of Aster. The next day 6 out of the 7 had laid eggs in clusters containing from 50 to 225 eggs in each. Hundreds of caterpillars were obtained, each brood being kept separate, and the butterflies began to emerge on June 29th, the several stages being: – egg six days, larva twenty-two, chrysalis five. Some of the butterflies did not emerge till the 15th of July. Just after this date one brood was taken to the Catskills, where they pupated, and in this state were sent back to Coalburgh. There was no difference in the length of the different stages of this brood and the others which had been left at Coalburgh, and none of either lot became lethargic. The butterflies from these eggs of May were all Tharos, with the exception of 1 female Marcia, var. C. Thus the first generation of Marcia from the hibernating larvæ furnishes a second generation of Tharos.

Exp. 3. – On July 16th, at Coalburgh, eggs were obtained from several females, all Tharos, as no other form was flying. In four days the eggs hatched; the larval stage was twenty-two, and the pupal stage seven days; but, as before, many larvæ lingered. The first butterfly emerged on August 18th. All were Tharos, and none of the larvæ had been lethargic. This was the third generation from the second laying of eggs.

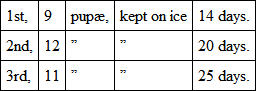

Exp. 4. – On August 15th, at Coalburgh, eggs were obtained from a female Tharos, and then taken directly to the Catskill Mountains, where they hatched on the 20th. This was the fourth generation from the third laying of eggs. In Virginia, and during the journey, the weather had been exceedingly warm, but on reaching the mountains it was cool, and at night decidedly cold. September was wet and cold, and the larvæ were protected in a warm room at night and much of the time by day, as they will not feed when the temperature is less than about 8° R. The first pupa was formed September 15th, twenty-six days from the hatching of the larvæ, and others at different dates up to September 26th, or thirty-seven days from the egg. Fifty-two larvæ out of 127 became lethargic after the second moult on September 16th, and on September 26th fully one half of these lethargic larvæ commenced to feed again, and moulted for the third time, after which they became again lethargic and remained in this state. The pupæ from this batch were divided into three portions: —

A. This lot was brought back to Coalburgh on October 15th, the weather during the journey having been cold with several frosty nights, so that for a period of thirty days the pupæ had at no time been exposed to warmth. The butterflies began to emerge on the day of arrival, and before the end of a week all that were living had come forth, viz., 9 males and 10 females. “Of these 9 males 4 were changed to Marcia var. C, 3 were var. D, and 2 were not changed at all. Of the 10 females 8 were changed, 5 of them to var. B, 3 to var. C. The other 2 females were not different from many Tharos of the summer brood, having large discal patches on under side of hind wing, besides the markings common to the summer brood.”

B. This lot, consisting of 10 pupæ, was sent from the Catskills to Albany, New York, where they were kept in a cool place. Between October 21st and Nov. 2nd, 6 butterflies emerged, all females, and all of the var. B. Of the remaining pupæ 1 died, and 3 were alive on December 27th. According to Mr. Edwards this species never hibernates in the pupal state in nature. The butterflies of this lot were more completely changed than were those from the pupæ of lot A.

C. On September 20th 18 of the pupæ were placed in a tin box directly on the surface of the ice, the temperature of the house being 3°-4° R. Some were placed in the box within three hours after transformation and before they had hardened; others within six hours, and others within nine hours. They were all allowed to remain on the ice for seven days, that being the longest summer period of the chrysalis. On being removed they all appeared dead, being still soft, and when they had become hard they had a shrivelled surface. On being brought to Coalburgh they showed no signs of life till October 21st, when the weather became hot (24°-25° R.), and in two days 15 butterflies emerged, “every one Marcia, not a doubtful form among them in either sex.” Of these butterflies 10 were males and 5 females; of the former 5 were var. C, 4 var. D, and 1 var. B, and of the latter 1 was var. C, and 4 var. D. The other 3 pupæ died. All the butterflies of this brood were diminutive, starved by the cold, but those from the ice were sensibly smaller than the others. All the examples of var. B were more intense in the colouring of the under surface than any ever seen by Mr. Edwards in nature, and the single male was as deeply coloured as the females, this also never occurring in nature.

Mr. Edwards next proceeds to compare the behaviour of the Coalburgh broods with those of the same species in the Catskills: —

Exp. 5. – On arriving at the Catskills, on June 18th, a few male Marcia, var. D, were seen flying, but no females. This was exactly one month later than the first males had been seen at Coalburgh. The first female was taken on June 26th, another on June 27th, and a third on the 28th, all Marcia, var. C. Thus the first female was thirty-eight days later than the first at Coalburgh. No more females were seen, and no Tharos. The three specimens captured were placed on Aster, where two immediately deposited eggs61 which were forwarded to Coalburgh, where they hatched on July 3rd. The first chrysalis was formed on the 20th, its butterfly emerging on the 29th, so that the periods were: egg six, larva seventeen, pupa nine days. Five per cent. of the larvæ became lethargic after the second moult. This was, therefore, the second generation of the butterfly from the first laying of eggs. All the butterflies which emerged were Tharos, the dark portions of the wings being intensely black as compared with the Coalburgh examples, and other differences of colour existed, but the general peculiarities of the Tharos form were retained. This second generation was just one month behind the second at Coalburgh, and since, in 1875, eggs were obtained by Mr. Mead on July 27th and following days, the larvæ from which all hibernated, this would be the second laying of eggs, and the resulting butterflies the first generation of the following season.

Thus in the Catskills the species is digoneutic, the first generation being Marcia (the winter form), and the second the summer form. A certain proportion of the larvæ from the first generation hibernate, and apparently all those from the second.

Discussion of Results.– There are four generations of this butterfly at Coalburgh, the first being Marcia and the second and third Tharos. None of the larvæ from these were found to hibernate. The fourth generation under the exceptional conditions above recorded (Exp. 4) produced some Tharos and more Marcia the same season, a large proportion of the larvæ also hibernating. Had the larvæ of this brood been kept at Coalburgh, where the temperature remained high for several weeks after they had left the egg, the resulting butterflies would have been all Tharos, and the larvæ from their eggs would have hibernated.

The altitude of the Catskills, where Mr. Edwards was, is from 1650 to 2000 feet above high water, and the altitude of Coalburgh is 600 feet. The transference of the larvæ from the Catskills to Virginia (about 48° lat.) and vice-versa, besides the difference of altitude, had no perceptible influence on the butterflies of the several broods except the last one, in which the climatic change exerted a direct influence on part of them both as to form and size. The stages of the June Catskill brood may have been accelerated to a small extent by transference to Virginia, but the butterflies reserved their peculiarities of colour. (See Exp. 5.) So also was the habit of lethargy retained.62 The May brood, on the other hand, taken from Virginia to the Catskills, suffered no retardation of development. (See Exp. 2.) It might have been expected that all the larvæ of this last brood taken to the mountains would have become lethargic, but the majority resisted this change of habit. From all these facts it may be concluded “that it takes time to naturalize a stranger, and that habits and tendencies, even in a butterfly, are not to be changed suddenly.”63

It has been shown that Tharos is digoneutic in the Catskills and polygoneutic in West Virginia, so that at a great altitude, or in a high latitude, we might expect to find the species monogoneutic and probably restricted to the winter form Marcia. These conditions are fulfilled in the Island of Anticosti, and on the opposite coast of Labrador (about lat. 50°), the summer temperature of these districts being about the same. Mr. Edwards states, on the authority of Mr. Cooper, who collected in the Island, that Tharos is a rare species there, but has a wide distribution. No specimens were seen later than July 29, after which date the weather became cold, and very few butterflies of any sort were to be seen. It seems probable that none of the butterflies of Anticosti or Labrador produce a second brood. All the specimens examined from these districts were of the winter form.

In explanation of the present case Dr. Weismann wrote to Mr. Edwards: – “Marcia is the old primary form of the species, in the glacial period the only one. Tharos is the secondary form, having arisen in the course of many generations through the gradually working influence of summer heat. In your experiments cold has caused the summer generation to revert to the primary form. The reversion which occurred was complete in the females, but not in all the males. This proves, as it appears to me, that the males are changed or affected more strongly by the heat of summer than the females. The secondary form has a stronger constitution in the males than in the females. As I read your letter, it at once occurred to me whether in the spring there would not appear some males which were not pure Marcia, but were of the summer form, or nearly resembling it; and when I reached the conclusion of the letter I found that you especially mentioned that this was so! And I was reminded that the same thing is observable in A. Levana, though in a less striking degree. If we treated the summer brood of Levana with ice, many more females than males would revert to the winter form. This sex is more conservative than the male – slower to change.”

The extreme variability of P. Tharos was alluded to more than a century ago by Drury, who stated: – “In short, Nature forms such a variety of this species that it is difficult to set bounds, or to know all that belongs to it.” Of the different named varieties, according to Mr. Edwards, “A appears to be an offset of B, in the direction most remote from the summer form, just as in Papilio Ajax, the var. Walshii is on the further side of Telamonides, remote from the summer form Marcellus.” Var. C leads from B through D directly to the summer form, whilst A is more unlike this last variety than are several distinct species of the genus, and would not be suspected to possess any close relationship were it not for the intermediate forms. The var. B is regarded as nearest to the primitive type for the following reasons: – In the first place it is the commonest form, predominating over all the other varieties in W. Virginia, and moreover appears constantly in the butterflies from pupæ submitted to refrigeration. Its distinctive peculiarity of colour occurs in the allied species P. Phaon (Gulf States) and P. Vesta (Texas), both of which are seasonally dimorphic, and both apparently restricted in their winter broods to the form corresponding to B of Tharos. In their summer generation both these species closely resemble the summer form of Tharos, and it is remarkable that these two species, which are the only ones (with the exception of the doubtful Batesii) closely allied to Tharos, should alone be seasonally dimorphic out of the large number of species in the genus.