полная версия

полная версияThe Mentor: Rembrandt, Vol. 4, Num. 20, Serial No. 120, December 1, 1916

Rembrandt seems to have had a particular interest in making etchings of beggars. He delighted to draw them. These types were easy to find in Amsterdam at that time; but they may be called super-beggars, for as a critic says, “One is almost inclined to say that they cannot be beggars, because the master’s hand has endowed them with the warmth and splendor with which his artistic temperament clothed everything he looked at.”

Some of Rembrandt’s etchings have brought great prices. In most cases, however, these prices varied because of the “state” of the plates. The points of difference between these “states” arise from the additions and changes made by Rembrandt on the plates. A single impression of one of his etchings, “Rembrandt with a Sword,” was bought for about $10,000 in 1893. Another, “Ephraim Bonus with Black Ring,” brought about $9,750; while a third, the “Hundred Guilder Print,” fetched about $8,750.

Some may find in Rembrandt’s etching much that at first appears rough and uncouth. More apparent skill and ease in drawing may appear to have been shown by other etchers. But Rembrandt’s work may justly be termed big, for it was conceived on a grand scale by a genius and master.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATIONILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 4, No. 20, SERIAL No. 120COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INCREMBRANDT

Portrait of the Artist

By Himself

In the Collection of Mr. Henry C. Frick, New York City

Entered as second-class matter March 10, 1913, at the postoffice at New York, N. Y., under the act of March 3, 1879. Copyright, 1916, by The Mentor Association, Inc.

The visitor to the Netherland art galleries should leave his notions of Greek and Italian art with his umbrella, at the entrance. Holland is no place to talk about canons of proportion or types of beauty or ideals of any kind. The Dutch are now, as they have always been, a people confronted by the realities of existence, and see life, literature, and art as facts rather than as fancies. There has never been much romance about them, but, on the contrary, a realization of the existent, a grasp of the truth and vitality of things, a keen penetration into the human problem. There never was any need for far-fetched fancies or ideals. The life about them interested and impressed them, and, from the very beginning, the Dutch painters were painting the portrait of their own land and people. The result was an art that has a distinct quality of its own – just as distinct a quality as the art of Persia or Japan. You would not think of judging Japanese art by that of Italy. Why then think of Dutch art in any other terms than its own?

Rembrandt and Raphael

PORTRAIT OF A MAN

Altman Collection of Metropolitan Museum, New York

To carry out the thought in illustration, it may be said that Rembrandt, the great Dutchman, was the very opposite of Raphael, the great Italian. He painted no allegories on Vatican walls, was not led away by Renaissance revivals of Greek form, dreamed no dreams of uniting pagan types with Christian ideals. Even technically he was widely different from Raphael. He painted the easel picture in oils, had no love whatever for Italian line and composition, did all his drawing and modeling by catches of shadow, and produced his most startling effects by the dramatic use of light and color. In all this Rembrandt was merely reflecting his time and his people in his own ingenious way. He was emphatically true to the Dutch point of view, and today his art is full of truth, force, vitality, character. In fact, that word “character” is the keynote to all his work. It furthermore explains that æsthetic paradox, sometimes applied to Rembrandt, “the beauty of the ugly.” For many of his people are ugly, if we regard them for the straightness of their foreheads and noses, the oval of their chins, or the proportions of their figures; but they are beautiful in their simplicity of presence, their unconscious sincerity, their profound truth of character.

THE ARCHITECT

In the Gallery at Cassel, Germany

Rembrandt as a Leader

No country in Europe produced a finer quality of art, or a more learned school of craftsmen, than Holland. There was a master genius there as elsewhere, and that genius was Rembrandt. He came when Holland had reached her highest pitch of power – came on the crest of the wave of which he and his fellow painters were the light and color. He has been acclaimed as her great painter and he deserves that title, for of all the Dutch masters he was practically the only one who was universal in his scope. His art alone, in its appeal, travels beyond the confines of the Netherlands. What he has to say is world-embracing, and finds sympathetic response with all peoples. He is profound in his humanity, in his penetration into life problems, in his sympathy with his fellow man. The poor, mean-looking Amsterdam Jews that he portrayed in so many of his pictures are pathetic in their humility, their suffering, their patience. He was always taking for models the humble, the despised, the lowly. His heart seemed to go out to them.

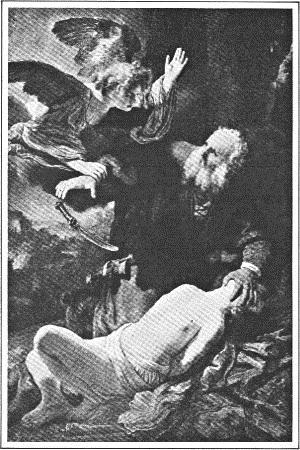

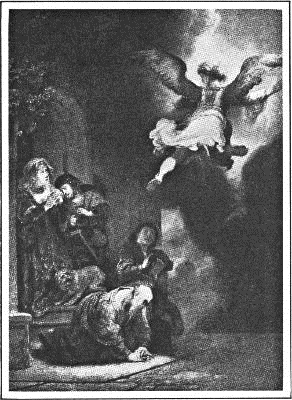

His Biblical Pictures

And with such types what a new interpretation he gave the Bible! How he realized Bible truth and brought it home to his own people by using the Jew of the quarter and the boor of the polder for models! Look at the “Supper at Emmaus” – look for the intensity of the types rather than for any regularity of form. What pathos in the pale, blue-lipped Christ, with the phosphorescent glimmer of the tomb about the architecture at the back! What amazement in the disciples at the table! What fear in the boy bringing in the dish! This was perhaps the first time in art that the “Supper at Emmaus” was made real and believable. The story was not only realized, but humanized. All of Rembrandt’s Biblical pictures were of this nature. Look again at the “Manoah’s Prayer,” or the “Tobit and the Angel,” or the “Sacrifice of Abraham.” They are Dutch types again, in Dutch costumes and surroundings. Rembrandt knew very well that the Biblical characters were not Dutch in type, and that the people in the time of Christ did not dress like the boors and burghers of Holland. He purposely painted his own people in their native costumes, that he might the better and the more forcefully bring realization home to them. It was not, is not, affectation. Study the Manoah and his wife, the Abraham, the family of Tobit on the doorstep, and you cannot find in all art people of more unconscious sincerity. Rembrandt believed in them. And that is why you and I believe in them today.

Rembrandt as a Portrait Painter

JAN HERMANSZ KRUL

In the Gallery at Cassel, Germany

PORTRAIT OF JOHN SIX

In the Six Gallery, Amsterdam

WOMAN WITH PINK

In the Gallery at Cassel, Germany

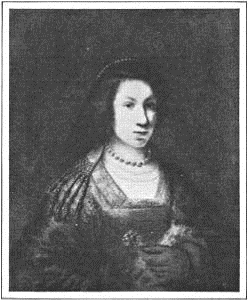

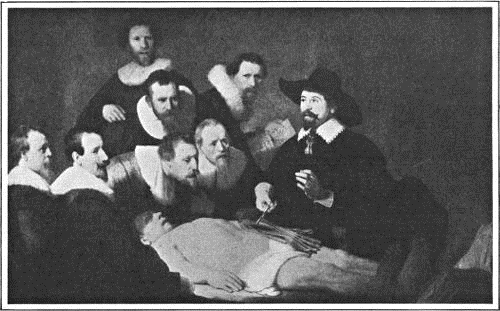

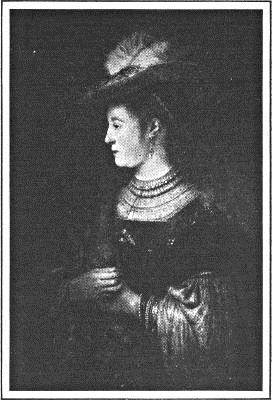

Rembrandt painted many Biblical pictures, which are at present widely scattered throughout the European galleries. In all of them he gave a new interpretation, a profound insight, a real meaning, to Scriptural story. In addition he painted many figure compositions of a historical or mythological cast. But his great success, after all said and done, was with the portrait. His technical methods were well suited to the portrait, and he was unsurpassed in giving the truth of presence in his sitter. The quiet dignity of his Dutch burghers, their repose and simplicity, the complete absence of anything like pretense about them, made up Rembrandt’s point of view; but to this he added a cunning hand and a technical skill that were wonderful. How superbly with his catches of light and shade he could draw an eye, a forehead, a nose, a chin! How instantly and inevitably he caught the salient feature and turned it by sharp emphasis into positive expression! What significance he could get out of an outstretched hand, a bent back, a bowed head! These were features wherewith he proclaimed the character of his sitter. The “Portrait of an Old Lady,” in the National Gallery, London, has the flabby cheek, the trembling lip, the wrinkled brow of the aged; but you can also see that hers has been a life of suffering, and that the eyes have often been blinded with tears. On the contrary, the “Portrait of a Man” – the so-called Sobieski, at Petrograd, has the determination and force of the warrior. It has grip and firmness and courage about it. These are not only in the features, but Rembrandt has even put them in the brush work – the manner of handling. Again, by way of contrast, the heads in the “Lesson in Anatomy” are put in calmly, serenely, inevitably just right. What intelligence, seriousness, and living presence they have! They are what might be called speaking likenesses, in the sense that all they lack of life is speech. And what can one say that will adequately describe the loveliness of mood, the eternal womanly, in the “Portrait of Saskia,” at Cassel! It is a wonder as a piece of color, but still more wonderful as a characterization of the painter’s wife. Once more, for a further contrast, look at the “Portrait of Coppenol.” He is supposed to be a writing master because he is sharpening a quill pen, but whatever his profession or pursuit, have you any difficulty in seeing here a dull-witted person of very limited intelligence? The very fatness of the forehead, so remarkable in its realistic rendering, the narrow eyes, with their vacant stare, the pumpkin cheeks and head, the soft, lazy hands, seem to point to some clerk or pedagogue, who had not enough brains to know that he wanted more.

Rembrandt was easily one of the great group of portrait painters with Titian, Velasquez, and Holbein. And by this I mean no faint praise. It seems to be thought in some quarters that portraiture is somehow an inferior branch of painting. It is said to require no invention or imagination. But nothing could be more mistaken than such an idea. When we speak of Rembrandt, Titian, Velasquez, and Holbein we are speaking of the world’s great masters, and perhaps their most satisfactory masterpieces are their portraits. A painter who can adequately portray his fellow man, as Rembrandt did, has practically said the last word in art. That Rembrandt had this gift and accomplishment is evidenced by the high esteem in which his work is held by painters even to this day.

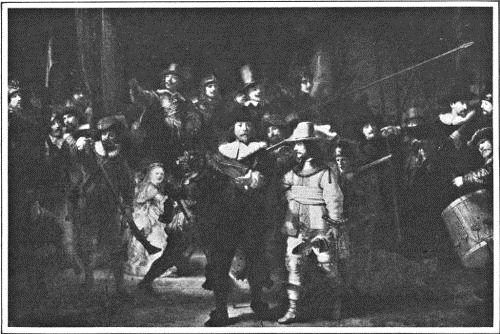

THE NIGHT WATCH

In the Ryks Museum, Amsterdam

A fine gravure reproduction of this painting appears in The Mentor, Number 17, “Dutch Masterpieces.”

His Technical Method

There was no trick about Rembrandt’s painting. He was no slave to a peculiar color, canvas or brush. He painted at times with a palette knife: at other times with his thumb. He kneaded the surface, ploughed through it when it was wet, did almost anything to get effects by catches of light and shade whereby he drew and modeled. But none of these small peculiarities explains his technical success. His methods were sound enough, and for the most part were known before his day; but he applied them better and increased their carrying power. He has been called the master of light and shade, and so, indeed, he was within a limited range. It was the same light and shade known to Leonardo, Giorgione, and Carravagio, and probably Rembrandt got it from pictures of the Neapolitan School, though he never was in Italy. But Rembrandt improved upon the Italian method of using shadow. He made it transparent, enveloping, mysterious. And its antithesis, light, he made penetrating and dramatic by putting it in sharp contrast. Out of the two he got wonderful effects. In doing the portrait head, for instance, he threw his highest light on the collar, the nose, the chin, the forehead. This high light ran off quickly into half-light and then into shadow, so that by the time the ear or side of the neck was reached, dark, even black, notes were used. The decrease was rapid; in fact often violent, but this only served to focus the attention more keenly upon the dominant features of the face. The result was what has been called “forced,” but it was very effective. It was the same effect that one sees today at the opera, when the chief actor is in the spot-light and the rest of the stage is in gloom.

SYNDICS OF THE CLOTH HALL

In the Ryks Museum, Amsterdam

A fine gravure reproduction of this painting appears in The Mentor, Number 8, “Pictures We Love to Live With.”

The Night Watch

But this violent focusing of light had its limitations even in Rembrandt’s hands. The “Night Watch” exemplifies them. This was to be a portrait group of the sixteen members of the Frans Banning Cock Shooting Company. The members wanted their portraits painted in a group, after the manner of the time, and Rembrandt conceived the idea of painting the portraits and making a stirring picture of the company coming out of its quarters, at one and the same time. It was an ambitious scheme, and not wholly successful, because here came in the limitations of his method. He painted sixteen portraits with his spot-light illumination, each one being completed under its own light. The picture lacked that one light which should have bound together the whole company. As a result there were sixteen separate portraits on the one canvas, held together in measure by shadow, color and atmosphere, but spotty in the lighting. The French writers of the eighteenth century could not understand the lighting, and were led to think the picture represented a night scene. They called it the “Ronde de Nuit,” and, later, Sir Joshua Reynolds translated this into “Night Watch.” But nothing is more certain than that Rembrandt intended it for a day scene in full sunlight. It was simply his arbitrary way of handling light that made a night effect out of daylight.

THE ANATOMY LESSON

In the Hague Museum

That is about the only criticism that can be lodged against the “Night Watch.” Light and color have both been sacrificed to shadow; but when that is conceded the picture still remains a marvel of color, shadow, and atmosphere, and a wonder of life and action. The movement – the bustle of it – is superb. The Captain and his Lieutenant in the foreground are in full light, but back of them and around them, emerging out of the gloom, are nebulous heads, flashing casques, plumes, halberds, guns, drums, dogs, street urchins – all the belongings of a militia company on parade. They are not only wonderful in their action, but in their mystery of appearance, coming out of shadow depths into light. Of course, the picture was not entirely satisfactory to the sixteen. They had bargained for their portraits, and little knew then how cheaply they were purchasing immortality. Those in the background complained that they were not sufficiently spot-lighted, not treated with sufficient importance; in fact, subordinated to those in the front row. But the picture, as a picture, is certainly successful, is a great favorite with all art-lovers, and in the Ryks Museum in Amsterdam, where it now hangs, it is considered one of the world’s great masterpieces. Truer lighting – that is truer to the facts of general illumination – is seen in the earlier “Lesson in Anatomy” and the later “Syndics of the Cloth Hall,” but neither picture has the fascination nor the imagination of the “Night Watch.”

Rembrandt’s Styles

THE SACRIFICE OF ABRAHAM

In the Old Pinacothek, Munich

THE ANGEL LEAVING TOBIT

In the Gallery of the Louvre, Paris

BLESSING OF JACOB

In the Gallery at Cassel, Germany

Rembrandt’s work is usually divided into three different periods. At first his method of handling was calm, measured, even at times smooth. His light and color were gray, as also his backgrounds. This period has been called his “gray period.” The “Lesson in Anatomy,” the “Sacrifice of Abraham,” the “Coppenol,” the “Elizabeth Bas,” the “Old Lady” of the National Gallery, London, all illustrate this early manner. It was gradually encroached upon and finally superseded by a fuller, freer handling of the brush, with much warmer color and light, tending toward reddish gold. This has been called his “golden period,” and marks the midday of his career. The beautiful “Saskia,” at Cassel, and the so-called “Sobieski,” at Petrograd, illustrate the beginning of this period – the changing from gray to warmer notes of red, yellow, and gold. The “Woman with the Pink,” at Cassel, the “Manoah’s Prayer,” at Dresden, the “Night Watch,” were done further along in this middle period. It was the time when Rembrandt was in his full strength, saw comprehensively, handled a full palette of color, and was almost infallibly accurate with his hand. In his third and last period Rembrandt’s work became rather hot and foxy in color, dark in illumination, kneaded and thumbed in the surface, and sometimes uncertain in drawing. He was expanding into a larger view and vision up to the last – seeing objects in their broader relations and proportions rather than in their surfaces. Toward the close he often slurred the surfaces, neglected textual qualities, and threw his whole force into the rendering of mass in relation to light, air, and color. The pictures of this period are hard for the beginner in art to understand, because he is misled by the roughness of the surfaces, the messy state of the pigments, the apparent fumbling, kneading, rubbing out and amending, of the brush work. But, as we have said, Rembrandt was purposely slurring surface truths for the greater truths of bulk, weight, and general relationship. The best example of this late work among our illustrations is the “Syndics of the Cloth Hall,” in the Ryks Museum, Amsterdam. In it Rembrandt went back to his early method of lighting, but continued with his late manner of handling and coloring. It is superbly broad in vision, absolute in its truth to life, and convincing in its incident. The cloth merchants are seated about a table, perhaps figuring up their year’s balance, when someone opens the door to enter and they all look up to see the incomer. Nothing could be simpler, more direct, or truer. Rembrandt never painted anything better. For here he completely fulfilled expectations. Many of his later canvases he could not complete. The “Blessing of Jacob,” at Cassel, for instance, he probably gave up in despair, or was working upon at the time of his death. He had reached a pitch in his career when he saw and strove for things that his hand or brush could not realize or pin down to canvas. That is the great stone wall that even genius encounters and cannot surmount.

The Master’s Life

PORTRAIT OF AN OLD LADY

In the National Gallery, London

The story of Rembrandt’s career is recited elsewhere in this number of The Mentor, but it may be said here that it was not different from that of many other painters. He came up to Amsterdam from the outlying country, and achieved celebrity at an early age. Praise and pay and pupils poured in upon him. He married the beautiful Saskia and was happy. But as he expanded in vision and methods he went beyond the understanding and the appreciation of his public. His pupils, such as Bol and Flinck, who had a more commonplace point of view, and a smoother, prettier style of painting, outdid him in public favor. The public began to desert him, the fair Saskia died, the great master fell upon evil days, and finally passed out in penury and want – evidently neglected and possibly forgotten by the age and people he had done so much to glorify. The record of his death in the Burial Book of the Wester Kirk, Amsterdam, is pathetic in its meagerness. “Tuesday, 8th Oct., 1669. Rembrandt van Rijn, painter on the Roozegraft, opposite the Doolhof. Leaves two children.” It almost looks as though he were identified only by the squalid quarters in which he died. And this was Rembrandt, the greatest master north of the Alps, and a genius of almost Shakespearian quality!

Many Pictures Attributed to Him

SASKIA VAN ULENBURGH

In the Gallery at Cassel, Germany

A fine gravure reproduction of this painting appears in The Mentor, Number 28.

It seems that not only was Rembrandt and his art misunderstood in his own time, but that he is still misunderstood at the present time. This is in measure due to many pictures which are mistakenly attributed to him. One need not be an expert to find it strange that of twenty pupils of Rembrandt, who painted more or less in his style, there remain hardly twenty pictures apiece, and of some of them not even one. What paralyzed their hands or destroyed their works? What became of their pictures? You begin to get a glimmer of light when you understand that to Rembrandt there are assigned a thousand or fifteen hundred examples; that these are painted in fifteen or twenty different styles, though all superficially resembling Rembrandt’s style. Almost everything that is Rembrandtesque, or even casually resembles Rembrandt, has been signed up and sold as his since the master came back to popular favor. The name is one that now brings thousands of dollars in the auction room, and what wonder that it is often misused!

These Rembrandtesque pictures were done by other hands than his, are pupils’ works, or school work or copies, or, in a few cases, forgeries. Rembrandt’s work has never been critically studied as that of Leonardo or Giorgione (jore-joe´-nee). Strange, again, is it not, that Leonardo and Giorgione in the final analysis should have less than a dozen pictures apiece left to them, while Rembrandt should still be given his thousand? Northern art has not had a critical searchlight turned upon it, as had Italian art thirty years ago. When it does, the present catalogue of Rembrandts will crumble. In the meantime, the art student would better accept Rembrandt only in his best authenticated works, such, for instance, as are reproduced in this number of The Mentor. Half of the so-called Rembrandts in the European galleries are now to be taken with a grain of salt. They may be, and often are, exceedingly good pictures, but they are not by Rembrandt.

SUPPLEMENTARY READING

GREAT MASTERS OF DUTCH AND FLEMISH PAINTING Bode London, 1909.

OLD MASTERS OF BELGIUM AND HOLLAND Fromentin Boston, 1882.

THE DUTCH SCHOOL OF PAINTING Havard London, 1885.

REMBRANDT Michel New York, 1894.