полная версия

полная версияThe Story of Florence

Also beyond the Porta al Prato (about an hour and a half by the tramway from behind Santa Maria Novella), is the Villa Reale of Poggio a Caiano, superbly situated where the Pistoian Apennines begin to rise up from the plain. The villa was built by Giuliano da San Gallo for Lorenzo, and the Magnifico loved it best of all his country houses. It was here that he wrote his Ambra and his Caccia col Falcone; in both of these poems the beautiful scenery round plays its part. When Pope Clement VII. sent the two boys, Ippolito and Alessandro, to represent the Medici in Florence, Alessandro generally stayed here, while Ippolito resided within the city in the palace in the Via Larga. When Charles V. came to Florence in 1536 to confirm Alessandro upon the throne, he declared that this villa "was not the building for a private citizen." Here, too, the Grand Duke Francesco and Bianca Cappello died, on October 19th and 20th, 1587, after entertaining the Cardinal Ferdinando, who thus became Grand Duke; it was said that Bianca had attempted to poison the Cardinal, and that she and her husband had themselves eaten of the pasty that she had prepared for him. It appears, however, that there is no reason for supposing that their deaths were other than natural. At present the villa is a royal country house, in which reminiscences of the Re Galantuomo clash rather oddly with those of the Medicean Princes. All round runs a loggia with fine views, and there are an uninteresting park and garden. The classical portico is noteworthy, all the rest being of the utmost simplicity.

Within the palace a large room, with a remarkably fine ceiling by Giuliano da San Gallo, is decorated with a series of frescoes from Roman history intended to be typical of events in the lives of Cosimo the Elder and Lorenzo the Magnificent. Vasari says that, for a villa, this is la più bella sala del mondo. The frescoes, ordered by Pope Leo X. and the Cardinal Giulio, under the direction of Ottaviano dei Medici, were begun by Andrea dei Sarto, Francia Bigio and Jacopo da Pontormo, left unfinished for more than fifty years, and then completed by Alessandro Allori for the Grand Duke Francesco. The Triumph of Cicero, by Francia Bigio, is supposed to typify the return of Cosimo from exile in 1434; Caesar receiving tribute from Egypt, by Andrea del Sarto, refers to the coming of an embassy from the Soldan to Lorenzo in 1487, with magnificent gifts and treasures. Andrea's fresco is full of curious beasts and birds, including the long-eared sheep which Lorenzo naturalised in the grounds of the villa, and the famous giraffe which the Soldan sent on this occasion and which, as Mr Armstrong writes, "became the most popular character in Florence," until its death at the beginning of 1489. The Regent of France, Anne of Beaujeu, made ineffectual overtures to Lorenzo to get him to make her a present of the strange beast. This fresco was left unfinished on the death of Pope Leo in 1521, and finished by Alessandro Allori in 1582. The charming mythological decorations between the windows are by Jacopo da Pontormo. The two later frescoes by Alessandro Allori, painted about 1580, represent Scipio in the house of Syphax and Flamininus in Greece, which typify Lorenzo's visit to Ferrante of Naples, in 1480, and his presence at the Diet of Cremona in 1483, on which latter occasion, as Mr Armstrong puts it, "his good sense and powers of expression and persuasion gave him an importance which the military weakness of Florence denied to him in the field"–but the result was little more than a not very honourable league of the Italian powers against Venice. The Apples of the Hesperides, and the rest of the mythological decorations in continuation of Pontormo's lunette, are also Allori's. The whole has an air of regal triumph without needless parade.

The road should be followed beyond the villa, in order to ascend to the left to the little church among the hills. A superb view is obtained over the plain to Florence beyond the Villa Reale lying below us. Behind, we are already among the Apennines. A beautiful glimpse of Prato can be seen to the left, four miles away.

Prato itself is about twelve miles from Florence. It was a gay little town in the fifteenth century, when it witnessed "brother Lippo's doings, up and down," and heard Messer Angelo Poliziano's musical sighings for the love of Madonna Ippolita Leoncina. A few years later it listened to the voice of Fra Girolamo Savonarola, and at last its bright day of prosperity ended in the horrible sack and carnage from the Spanish soldiery under Raimondo da Cardona in 1512. Its Duomo–dedicated to St. Stephen and the Baptist–a Tuscan Romanesque church completed in the Gothic style by Giovanni Pisano, with a fine campanile built at the beginning of the fourteenth century, claims to possess a strange and wondrous relic: nothing less than the Cintola or Girdle of the Blessed Virgin, delivered by her–according to a pious and poetical legend–to St. Thomas at her Assumption, and then won back for Christendom by a native of Prato, Michele Dagonari, in the Crusades. Be that as it may, what purports to be this relic is exhibited on occasions in the Pulpito della Cintola on the exterior of the Duomo, a magnificent work by Donatello and Michelozzo, in which the former master has carved a wonderful series of dancing genii hardly, if at all, inferior to those more famous bas-reliefs executed a little later for the cantoria of Santa Maria del Fiore. Within, over the entrance wall, is a picture by Ridolfo Ghirlandaio of the Madonna giving the girdle to the Thomas who had doubted. And in the chapel on the left (with a most beautifully worked bronze screen, with a lovely frieze of cupids, birds and beasts–the work of Bruno Lapi and Pasquino di Matteo, 1444-1461), the Cintola is preserved amid frescoes by Agnolo Gaddi setting forth the life of Madonna, her granting of Prato's treasure to St Thomas at the Assumption, and its discovery by Michele Dagonari.

The church is rich in works of Florentine art–a pulpit by Mino da Fiesole and Antonio Rossellino; the Madonna dell' Ulivo by Giuliano da Maiano; frescoes said to be in part by Masolino's reputed master Starnina in the chapel to the right of the choir. But Prato's great artistic glory must be sought in Fra Lippo Lippi's frescoes in the choir, painted between 1452 and 1464. These are the great achievements of the Friar's life. On the left is the life of St. Stephen, on the right that of the Baptist. They show very strongly the influence of Masaccio, and make us understand why the Florentines said that the spirit of Masaccio had entered into the body of Fra Filippo. Inferior to Masaccio in most respects, Filippo had a feeling for facial beauty and spiritual expression, and for a certain type of feminine grace which we hardly find in his prototype. The wonderful figure of the dancing girl in Herod's banquet, and again her naïve bearing when she kneels before her mother with the martyr's head, oblivious of the horror of the spectators and merely bent upon showing us her own sweet face, are characteristic of Lippo, as also, in another way, his feeling for boyhood shown in the little St. John's farewell to his parents. The Burial of St. Stephen is full of fine Florentine portraits in the manner of the Carmine frescoes. The dignified ecclesiastic at the head of the clergy is Carlo dei Medici, the illegitimate son of Cosimo. On the extreme right is Lippo himself. Carlo looks rather like a younger, more refined edition of Leo X.

It was while engaged upon these frescoes that Lippo Lippi was commissioned by the nuns of Santa Margherita to paint a Madonna for them, and took the opportunity of carrying off Lucrezia Buti, a beautiful girl staying in the convent who had sat to him as the Madonna, during one of the Cintola festivities. Lippo appears to have been practically unfrocked at this time, but he refused the dispensation of the Pope who wished him to marry her legally, as he preferred to live a loose life. Between the station and the Duomo you can see the house where they lived and where Filippino Lippi was born. Opposite the convent of Santa Margherita is a tabernacle containing a wonderfully beautiful fresco by Filippino, a Madonna and Child with Angels, adored by St. Margaret and St. Catherine, St. Antony and St. Stephen. All the faces are of the utmost loveliness, and the Catherine especially is like a foretaste of Luini's famous fresco at Milan. In the town picture gallery there are four pictures ascribed to Lippo Lippi–all four of rather questionable authenticity–and one by Filippino, a Madonna and Child with St. Stephen and the Baptist, which, although utterly ruined, appears to be genuine. The Protomartyr and the Precursor seem always inseparable throughout the faithful little city of the Cintola.

Prato can likewise boast some excellent terracotta works by Andrea della Robbia, both outside the Duomo and in the churches of Our Lady of Good Counsel and Our Lady of the Prisons. This latter church, the Madonna delle Carceri, reared by Giuliano da San Gallo between 1485 and 1491, is perhaps the most beautiful and most truly classical of all Early Renaissance buildings in Tuscany.

Ten miles beyond Prato lies Pistoia, at the very foot of the Apennines, the city of Dante's friend and correspondent, Messer Cino, the poet of the golden haired Selvaggia, he who sang the dirge of Caesar Henry; the centre of the fiercest faction struggles of Italian history. It was the Florentine traditional policy to keep Pisa by fortresses and Pistoia by factions. It lies, however, beyond the scope of the present book, with the other Tuscan cities that owned the sway of the great Republic. San Gemignano, that most wonderful of all the smaller towns of Tuscany, the city of "the fair towers," of Santa Fina and of the gayest of mediæval poets, Messer Folgore, comes into another volume of this series.

But it is impossible to conclude even the briefest study of Florence without a word upon that Tuscan Earthly Paradise, the Casentino and upper valley of the Arno, although it lies for the most part not in the province of Florence but in that of Arezzo. It is best reached by the diligence which runs from Pontassieve over the Consuma Pass–where Arnaldo of Brescia, who lies in the last horrible round of Dante's Malebolge, was burned alive for counterfeiting the golden florins of Florence–to Stia.56 A whole chapter of Florentine history may be read among the mountains of the Casentino, writ large upon its castles and monasteries. If the towers of San Gemignano give us still the clearest extant picture of the life led by the nobles and magnates when forced to enter the cities, we can see best in the Casentino how they exercised their feudal sway and maintained for a while their independence of the burgher Commune. The Casentino was ruled by the Conti Guidi, that great clan whose four branches–the Counts of Romena, the Counts of Porciano, the Counts of Battifolle and Poppi, the Counts of Dovadola (to whom Bagno in Romagna and Pratovecchio here appear to have belonged)–sprang from the four sons of Gualdrada, Bellincion Berti's daughter. Poppi remains a superb monument of the power and taste of these "Counts Palatine of Tuscany"; its palace on a small scale resembles the Palazzo Vecchio of Florence. Romena and Porciano, higher up stream, overhanging Pratovecchio and Stia, have been immortalised by the verse and hallowed by the footsteps of Dante Alighieri. Beneath the hill upon which Poppi stands, an old bridge still spans the Arno, upon which the last of the Conti Guidi, the Count Francesco, surrendered in 1440 to the Florentine commissary, Neri Capponi. After the second expulsion of the Medici from Florence, Piero and Giuliano for some time lurked in the Casentino, with Bernardo Dovizi at Bibbiena.

Throughout the Casentino Dante himself should be our guide. There is hardly another district in Italy so intimately connected with the divine poet; save only Florence and Ravenna, there is, perhaps, none where we more frequently need to have recourse to the pages of the Divina Commedia. With the Inferno in our hands, we seek out Count Alessandro's castle of Romena and what purports to be the Fonte Branda, below the castle to the left, for whose waters–even to cool the thirst of Hell–Maestro Adamo would not have given the sight of his seducer sharing his agony. With the Purgatorio we trace the course of the Arno from where, a mere fiumicello, it takes its rise in Falterona, and runs down past Porciano and Poppi to sweep away from the Aretines, "turning aside its muzzle in disdain." There is a tradition that Dante was imprisoned in the castle of Porciano. We know that he was the guest of various members of the Conti Guidi at different times during his exile; it was from one of their castles, probably Poppi, that on March 31st and April 16th, 1311, he directed his two terrible letters to the Florentine government and to the Emperor Henry. It was in the Casentino, too, that he composed the Canzone Amor, dacchè convien pur ch'io mi doglia, "Love, since I needs must make complaint," one of the latest and most perplexing of his lyrics.

The battlefield of Campaldino lies beyond Poppi, on the eastern side of the river, near the old convent and church of Certomondo, founded some twenty or thirty years before by two of the Conti Guidi to commemorate the great Ghibelline victory of Montaperti, but now to witness the triumph of the Guelfs. The Aretines, under their Bishop and Buonconte da Montefeltro, had marched up the valley along the direction of the present railway to Bibbiena, to check the ravages of the Florentines who, with their French allies, had made their way through the mountains above Pratovecchio and were laying waste the country of the Conti Guidi. It was on the Feast of St. Barnabas, 1289, that the two armies stood face to face, and Dante riding in the Florentine light cavalry, if the fragment of a letter preserved to us by Leonardo Bruni be authentic, "had much dread and at the end the greatest gladness, by reason of the varying chances of that battle." There are no relics of the struggle to be found in Certomondo; only a very small portion of the cloisters remains, and the church itself contains nothing of note save an Annunciation by Neri di Bicci. But about an hour's walk from the battlefield, perhaps a mile from the foot of the hill on which Bibbiena stands, is a spot most sacred to all lovers of Dante. Here the stream of the Archiano, banked with poplars and willows, flows into the Arno; and here, at the close of that same terrible and glorious day, Buonconte da Montefeltro died of his wounds, gasping out the name of Mary. At evening the nightingales are loud around the spot, but their song is less sweet then the ineffable stanzas in the fifth canto of the Purgatorio in which Dante has raised an imperishable monument to the young Ghibelline warrior.

But, more famous than its castles or even its Dantesque memories, the Casentino is hallowed by its noble sanctuaries of Vallombrosa, Camaldoli, La Verna. Less noted but still very interesting is the Dominican church and convent of the Madonna del Sasso, just below Bibbiena on the way towards La Verna, hallowed with memories of Savonarola and the Piagnoni, and still a place of devout pilgrimage to Our Lady of the Rock. There is a fine Assumption in its church, painted by Fra Paolino from Bartolommeo's cartoon. Vallombrosa and Camaldoli, founded respectively by Giovanni Gualberto and Romualdus, have shared the fate of all such institutions in modern Italy.

La Verna remains undisturbed, that "harsh rock between Tiber and Arno," as Dante calls it, where Francis "received from Christ the final seal;" the sacred mountain from which, on that September morning before the dawn, so bright a light of Divine Love shone forth to rekindle the mediæval world, that all the country seemed aflame, as the crucified Seraph uttered the words of mystery–Tu sei il mio Gonfaloniere: "Thou art my standard-bearer." To enter the precincts of this sacred place, under the arch hewn out from between the rocks, is like a first introduction to the spirit of the Divina Commedia.

"Non est in toto sanctior orbe mons."

For here, at least, is one spot left in the world, where, although Renaissance and Reformation, Revolution and Risorgimento, have swept round it, the Middle Ages still reign a living reality, in their noblest aspect, with the poverelli of the Seraphic Father; and the mystical light, that shone out on the day of the Stigmata, still burns: "while the eternal ages watch and wait."

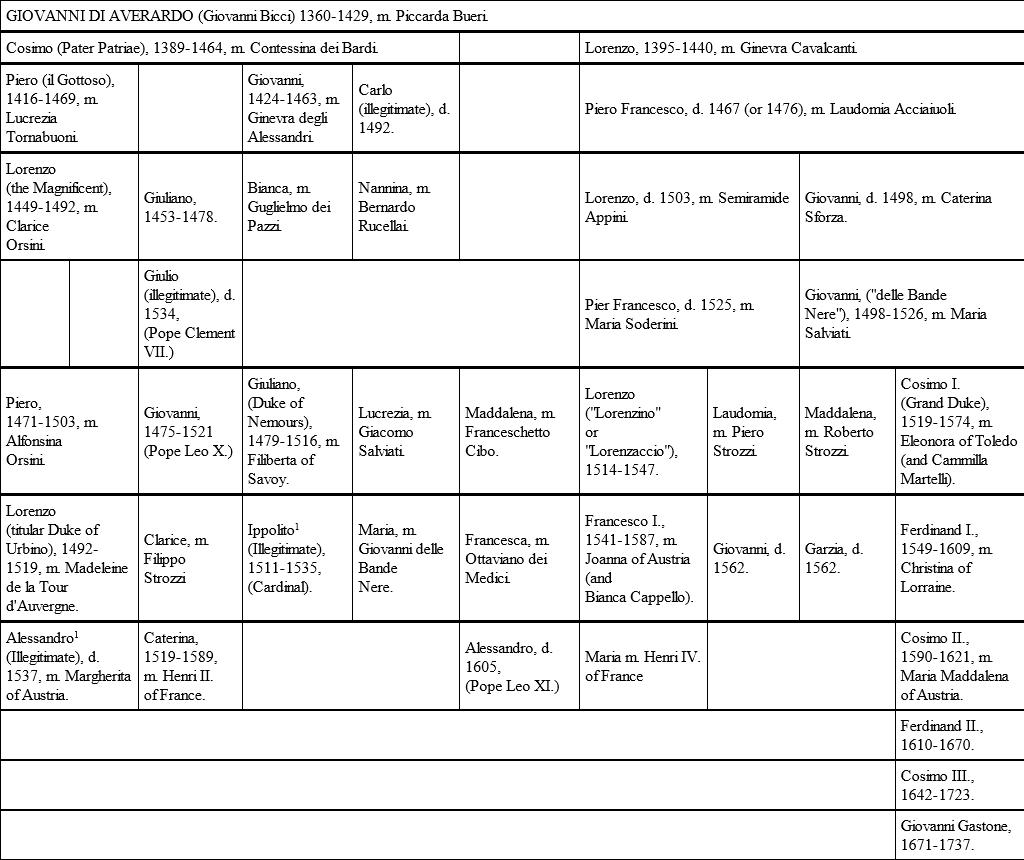

TABLE OF THE MEDICI

1The parentage of Ippolito and Alessandro is somewhat uncertain. The former was probably Giuliano's son by a lady of Pesaro, the latter probably the son of Lorenzo by a mulatto woman.

1

"Love, I demand to have my lady in fee,Fine balm let Arno be,The walls of Florence all of silver rear'd,And crystal pavements in the public way;With castles make me fear'd,Till every Latin soul have owned my sway."– Lapo Gianni (Rossetti).2

"For amongst the tart sorbs, it befits not the sweet fig to fructify."

3

"Let the beasts of Fiesole make litter of themselves, and not touch the plant, if any yet springs up amid their rankness, in which the holy seed revives of those Romans who remained there when it became the nest of so much malice."

4

"With these folk, and with others with them, did I see Florence in such full repose, she had not cause for wailing;

With these folk I saw her people so glorious and so just, ne'er was the lily on the shaft reversed, nor yet by faction dyed vermilion."

– Wicksteed's translation.5

"The house from which your wailing sprang, because of the just anger which hath slain you and placed a term upon your joyous life,

"was honoured, it and its associates. Oh Buondelmonte, how ill didst thou flee its nuptials at the prompting of another!

"Joyous had many been who now are sad, had God committed thee unto the Ema the first time that thou camest to the city.

"But to that mutilated stone which guardeth the bridge 'twas meet that Florence should give a victim in her last time of peace."

6

"And one who had both hands cut off, raising the stumps through the dim air so that their blood defiled his face, cried: 'Thou wilt recollect the Mosca too, ah me! who said, "A thing done has an end!" which was the seed of evil to the Tuscan people.'" (Inf. xxviii.)

7

The Arte di Calimala, or of the Mercatanti di Calimala, the dressers of foreign cloth; the Arte della Lana, or wool; the Arte dei Giudici e Notai, judges and notaries, also called the Arte del Proconsolo; the Arte del Cambio or dei Cambiatori, money-changers; the Arte dei Medici e Speziali, physicians and apothecaries; the Arte della Seta, or silk, also called the Arte di Por Santa Maria; and the Arte dei Vaiai e Pellicciai, the furriers. The Minor Arts were organised later.

8

Some years later a new officer, the Executor of Justice, was instituted to carry out these ordinances instead of leaving them to the Gonfaloniere. This Executor of Justice was associated with the Captain, but was usually a foreign Guelf burgher; later he developed into the Bargello, head of police and governor of the gaol. It will, of course, be seen that while Podestà, Captain, Executore (the Rettori), were aliens, the Gonfaloniere and Priors (the Signori) were necessarily Florentines and popolani.

9

Rossetti's translation of the ripresa and second stanza of the Ballata Perch'i' no spero di tornar giammai.

10

"Thou shall abandon everything beloved most dearly; this is the arrow which the bow of exile shall first shoot.

"Thou shalt make trial of how salt doth taste another's bread, and how hard the path to descend and mount upon another's stair."

– Wicksteed's translation.11

"On that great seat where thou dost fix thine eyes, for the crown's sake already placed above it, ere at this wedding feast thyself do sup,

"Shall sit the soul (on earth 'twill be imperial) of the lofty Henry, who shall come to straighten Italy ere she be ready for it."

12

i. e. The Nativity of the Blessed Virgin.

13

Purg. VI.–

"Athens and Lacedæmon, they who madeThe ancient laws, and were so civilised,Made towards living well a little signCompared with thee, who makest such fine-spunProvisions, that to middle of NovemberReaches not what thou in October spinnest.How oft, within the time of thy remembrance,Laws, money, offices and usagesHast thou remodelled, and renewed thy members?And if thou mind thee well, and see the light,Thou shalt behold thyself like a sick woman,Who cannot find repose upon her down,But by her tossing wardeth off her pain."– Longfellow.14

"In painting Cimabue thought that heShould hold the field, now Giotto has the cry,So that the other's fame is growing dim."15

The "Colleges" were the twelve Buonuomini and the sixteen Gonfaloniers of the Companies. Measures proposed by the Signoria had to be carried in the Colleges before being submitted to the Council of the People, and afterwards to the Council of the Commune.

16

From Mr Armstrong's Lorenzo de' Medici.

17

The Palle, it will be remembered, were the golden balls on the Medicean arms, and hence the rallying cry of their adherents.

18

The familiar legend that Lorenzo told Savonarola that the three sins which lay heaviest on his conscience were the sack of Volterra, the robbery of the Monte delle Doti, and the vengeance he had taken for the Pazzi conspiracy, is only valuable as showing what were popularly supposed by the Florentines to be his greatest crimes.

19

This Compendium of Revelations was, like the Triumph of the Cross, published both in Latin and in Italian simultaneously. I have rendered the above from the Italian version.

20

When Savonarola entered upon the political arena, his spiritual sight was often terribly dimmed. The cause of Pisa against Florence was every bit as righteous as that of the Florentines themselves against the Medici.

21

This Luca Landucci, whose diary we shall have occasion to quote more than once, kept an apothecary's shop near the Strozzi Palace at the Canto de' Tornaquinci. He was an ardent Piagnone, though he wavered at times. He died in 1516, and was buried in Santa Maria Novella.

22

"He who usurpeth upon earth my place, my place, my place, which in the presence of the Son of God is vacant,

"hath made my burial-ground a conduit for that blood and filth, whereby the apostate one who fell from here above, is soothed down there below."–Paradiso xxvii.

– Wicksteed's Translation.23

Sermon on May 29th, 1496. In Villari and Casanova, Scelte di prediche e scritti di Fra Girolamo Savonarola.

24

Professor Villari justly remarks that "Savonarola's attacks were never directed in the slightest degree against the dogmas of the Roman Church, but solely against those who corrupted them." The Triumph of the Cross was intended to do for the Renaissance what St Thomas Aquinas had accomplished for the Middle Ages in his Summa contra Gentiles. As this book is the fullest expression of Savonarola's creed, it is much to be regretted that more than one of its English translators have omitted some of its most characteristic and important passages bearing upon Catholic practice and doctrine, without the slightest indication that any such process of "expurgation" has been carried out.

25

See the Genealogical Table of the Medici.

26