полная версия

полная версияA True Account of the Battle of Jutland, May 31, 1916

Thus disposed the German Battle Fleet moved through the dark hours, on a straight course for Horn Reef, without meeting the expected attacks, which the strong Squadron I in the van was prepared to ward off. There really was no chance of engaging the British battleships, as the Grand Fleet had moved to the south before the German fleet crossed Lord Jellicoe’s course. The Nassau got out of station, when she struck a stray British destroyer in the darkness, and made for a morning rendezvous. The rest of the dreadnoughts of the High Seas Fleet met no delay nor mishap through the dark hours. Of the predreadnoughts, the battleship Pommern was sunk by a mine or torpedo, with loss of all hands.

Many of the destroyers had fired all their torpedoes, and these craft were used for emergencies. They were very necessary, as the disabled cruisers Rostock and Elbing were abandoned and blown up, and these destroyers did good service in taking off the crews. They also rescued the crew of the disabled Lützow, which was towed through the darkness until she was so down by the head that her screws spun in the air. She was abandoned and destroyed by a torpedo at 1.45 A.M. Admiral Scheer cites the fact that these events could happen, without disturbance by the enemy, as “proving that the English Naval forces made no attempt to occupy the waters between the scene of battle and Horn Reef.” (S)

As a matter of fact this did not need any proof, because the British fleet held steadily on its southerly course, without regard to the direction taken by the Germans. In the wake of the Grand Fleet were left scattered cruisers and destroyers – and there were many clashes between these and the Germans, but all were isolated fights and adventures of lame ducks. Some of these encounters were reported to Lord Jellicoe and there was much shooting, with explosions and fire lighting up the darkness.

Admiral Scheer thought that all this must have indicated his position, and, even after not encountering the expected night attacks, the German Admiral expected the British to renew the battle promptly at dawn. But in consequence of the British Admiral’s dispositions for the night, it is evident that the position of the German fleet was not developed, as Admiral Jellicoe himself says, until “the information obtained from our wireless directional stations during the early morning.” (J)

As dawn was breaking, “at about 2.47 A.M.” (J) June 1, Admiral Jellicoe altered course of his fleet to the north to retrace his path of the night before. His Sixth Division of battleships had dropped astern, out of sight. His cruisers and destroyers were badly scattered, and the British Admiral abandoned his intention of seeking a new battle on the first of June.

The straggling of portions of his fleet during the move through the darkness is explained by Lord Jellicoe, and this caused him to delay his search for the German fleet until he could pick up the missing craft. His return to find these was the reason for retracing the course of the night manœuvre. The following is quoted from Lord Jellicoe’s book: “The difficulty experienced in collecting the fleet (particularly the destroyers), due to the above causes, rendered it undesirable for the Battle Fleet to close the Horn Reef at daylight, as had been my intention when deciding to steer to the southward during the night. It was obviously necessary to concentrate the Battle Fleet and the destroyers before renewing action. By the time this concentration was effected it had become apparent that the High Seas Fleet, steering for the Horn Reef, had passed behind the shelter of the German mine fields in the early morning on their way to their ports.”

Admiral Scheer’s fleet had arrived off Horn Reef at 3 A.M., where he waited for the disabled Lützow. At 3.30 he learned that she had been abandoned. Up to that time the German Admiral had expected a new battle of fleets, but he soon divined that he was to be free from pressure on the part of his enemy. This was confirmed when Admiral Scheer learned through a German aircraft scout of the straggling of Lord Jellicoe’s ships. (L 11 was the airship reported by the British “shortly after 3.30.”) Admiral Scheer’s comment is: “It is obvious that this scattering of the forces – which can only be explained by the fact that after the day-battle Admiral Jellicoe had lost the general command – induced the Admiral to avoid a fresh battle.” Both commanders are consequently on record in agreement as to the reason for no new battle of fleets.

The Germans were thus enabled to proceed to their bases undisturbed. Admiral Scheer’s account of the return of the German fleet to its home ports, and of the condition of his ships, is convincing – and there is no longer any question as to the German losses. On the way home the Ostfriesland struck a mine, but was not seriously injured, making port without difficulty. Outside of the destruction of the Lützow, the German battle cruiser squadron was badly battered. The Seydlitz had great difficulty in making her berth, and the Derfflinger was also seriously damaged. To sum up the damage done to the battle cruisers of both fleets makes a sorry showing for this type of warship, which had so great a vogue before The World War.

Admiral Scheer states that, with the exception of his two battle cruisers, the German fleet was repaired and ready to go to sea again by the middle of August, and the Bayern (the first German warship to mount 38 c.m. – guns) had been added to the fleet. He also gives an account of another sortie (August 18 to 20, 1916). Later in the year the German fleet was reinforced by the Baden (38 c.m. – guns) and the battle cruiser Hindenburg, but at the end of 1916 the function of the High Seas Fleet was to keep the gates for the U-boats in the great German submarine campaign.

In this rôle of covering the operations of the submarines the German Battle Fleet had a very important influence upon the ensuing stages of the War. It was altogether a delusion to think that the career of the German fleet had been ended at Jutland – and that it “never came out.” On the contrary, Admiral Scheer’s fleet kept a wide area cleared for the egress and entrance of the German U-boats in their destructive campaign. If the German fleet had been destroyed in the Jutland action, it would have been possible for the Allies to put in place and maintain mine barrages close to the German bases. There is no need to add anything to this statement to show the great results that would have been gained, if the British had been able to win a decision in the Battle of Jutland.

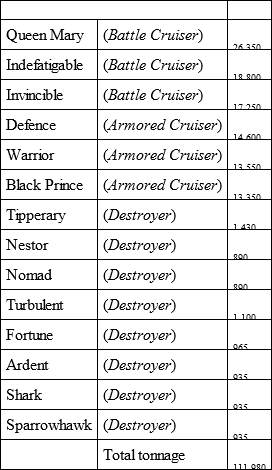

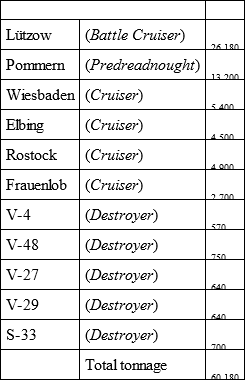

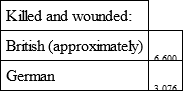

* * * * *The losses in the battle were as follows:

BRITISH

GERMAN

In the early British accounts of the battle there were fanciful tales of pursuit of the German ships, through the night, and even after Admiral Jellicoe’s Report the British public did not at first realize the situation at the end of the action. But after a time, when this was better understood, there arose one of the greatest naval controversies that have ever agitated Great Britain, centered around the alleged “defensive” naval policy for maintaining the supremacy of Great Britain on the seas, – the pros and cons as to closing the Germans while there was light, and keeping in touch through the dark hours.

This controversy as to the Battle of Jutland has been carried on with bitterness in Great Britain, and volumes of matter have been written that will be utterly useless, so far as a true story of the action is concerned. Partisans have made the mistake of putting on record arguments that have been founded on phases of the British operations – with imaginary corresponding situations of the enemy, which never existed in actual fact. The preceding account may be relied upon as tracing the main events of the battle – and the real course of the action shows that many briefs must be thrown out of court.

Putting aside these contentions, and seeking only to visualize the truth, one is forced to the conclusion that the chief cause of failure on the part of the British fleet was the obvious handicap that methods had not been devised in advance for decisive operations under the existing conditions.

The problem for the British was to unite two parts of a superior force, and to impose this united superior force with destructive effect upon the enemy. This problem was simplified by the fact that the weaker enemy voluntarily came into contact in a position where escape by flight was out of the question. On the other hand, the solution was made difficult by unusual conditions of mist and smoke.

The decision was missed through the lack of rehearsed methods, not only for effectively joining the British forces, but for bringing into contact the superior British strength, against an enemy who actually possessed the great advantage of rehearsed methods adapted to the existing conditions. These conditions must be realized in order to arrive at a fair verdict.

When considering the Battle of Jutland, we must not think in the old terms of small dimensions, but we must picture the long miles of battle lines wreathed in mist and smoke, the great areas of manœuvre – and the complicated difficulties that must beset anyone who was called to command in this first great battle of dreadnoughts. These widely extended manœuvres of ships, only intermittently visible, must not be thought of as merely positions on a chart or game-board.

Reviewing the course of the action, the conclusion cannot be avoided that, on the day of the battle and under its conditions, the Germans were better prepared in advance for a battle of fleets. In his book Lord Jellicoe states many advantages possessed by the German fleet in construction, armament, and equipment – but, as has been said, his revelation of the British lack of methods is more significant.

All these deficiencies cannot be charged against Admiral Jellicoe, and the persistent efforts to give him all the blame are unjust. Is there any real evidence that another man would have done better under the circumstances? The tendency of certain writers to laud Vice Admiral Beatty at the expense of Admiral Jellicoe does not seem justified. As has been noted, when contact was established with the German advance force, Beatty failed to bring his full strength into action against this isolated weaker enemy force. In the ensuing stages it cannot be denied that haphazard methods were in evidence.

The idea must be put aside that the German ships were a huddled, helpless prey “delivered” to the British Commander-in-Chief. On the contrary, as stated, the German battle cruisers had already closed up with the German battleships and the High Seas Fleet had been slowed down to correct its formations. Consequently at this stage the German fleet was in hand and ready to sheer off, by use of their well rehearsed elusive manœuvre of ships-right-about, with baffling concealment in smoke screens. It has been shown that after the Grand Fleet had completed deployment, the unsuspected situation existed in which Admiral Scheer’s fleet was again in close contact with the British fleet. It has also been explained that Vice Admiral Beatty made his much discussed signal, to “cut off” the German fleet, long after Admiral Scheer had put his fleet into safety by his third swing-around of the German ships. With these situations totally uncomprehended, it cannot be said that Vice Admiral Beatty had a firmer grasp upon the actual conditions than anyone else. The simple truth is, the British Command was always compelled to grope for the German ships, while his enemies were executing carefully rehearsed elusive manœuvres concealed in smoke – and the British were not prepared in advance to counter these tactics.

In the matter of signaling, the Germans were far ahead – in that they had their manœuvres carefully prepared in advance, to be executed with the minimum number of signals. The result was that, while the British Commander-in-Chief was obliged to keep up a constant succession of instructions by signals, the German Admiral was able to perform his surprising manœuvres with comparatively few master signals.8 Lord Jellicoe also emphasizes the great advantage possessed by the Germans in their recognition signals at night.

Sir Percy Scott, as already quoted, bluntly states: “The British Fleet was not properly equipped for fighting an action at night. The German Fleet was.” To this should be added the statement that the British fleet was not prepared in methods in advance to cope with the conditions of the afternoon of May 31. The German fleet was. Herein lay the chief cause for failure to gain a decision, when the one great opportunity of the war was offered to the British fleet.

In the three decades before The World War great strides had been made in naval development, with only the unequal fighting in the American War with Spain and in the East to give the tests of warfare. In this period it is probable that at different times first one navy would be in the lead and then another. It was the misfortune of the British in the Battle of Jutland that the Germans, at that time, were better prepared in equipment and rehearsed methods for an action under the existing conditions. This should be recognized as an important factor – and the failure to win a decision should not be wholly charged against the men who fought the battle.

The destroyer came to its own in the Battle of Jutland as an auxiliary of the battle fleet, both for offense and defense. The whole course of the action proved that a screen of destroyers was absolutely necessary. For offense, it might be argued truthfully that, of the great number of torpedoes used, very few hit anything. The Marlborough was the only capital ship reported struck in the real action,9 and she was able afterward to take some part in the battle, and then get back to her base. But above all things stands out the fact that it was the threat of night torpedo attacks by German destroyers, and the desire to safeguard the British capital ships from these torpedo attacks, which made the British fleet withdraw from the battlefield, and break off touch with the German fleet. Lord Jellicoe states that he “rejected at once the idea of a night action” on account of “first the presence of torpedo craft in such large numbers.” (J)

There is no question of the fact that this withdrawal of the British fleet had a great moral effect on Germany. Morale was all-important in The World War, and the announcement to the people and to the Reichstag had a heartening effect on the Germans at just the time they needed some such stimulant, with an unfavorable military situation for the Central Powers. It also smoothed over the irritation of the German people against the German Navy, at this time when Germany had been obliged to modify her use of the U-boats upon the demand of the United States. For months after the battle the esteem of the German people for the German Navy remained high, and this helped to strengthen the German Government. But the actual tactical result of the battle was indecisive. It may be said that the Germans had so manœuvred their fleet that a detached part of the superior British force was cut up, but the damage was not enough to impair the established superiority of the British fleet.

As a matter of fact the Battle of Jutland did not have any actual effect upon the situation on the seas. The British fleet still controlled the North Sea. The Entente Allies were still able to move their troops and supplies over water-ways which were barred to the Germans. Not a German ship was released from port, and there was no effect upon the blockade. After Jutland, as before, the German fleet could not impose its power upon the seas, and it could not make any effort to end the blockade. The Jutland action had cheered the German people but it had not given to Germany even a fragment of sea power.

From A Guide to the Military History of The World War, 1914–1918.

CHART NO. 2THE BATTLE OF JUTLAND(This chart is diagrammatic only)

Most of the published narratives have used many charts to trace the events of the action. It has been found possible to indicate all the essentials upon this one chart, which has been so placed that it can be opened outside the pages for use as the text is being read. It should be noted that superimposed indications have been avoided, where ships passed over the same areas (especially in the three German ships-right-about manœuvres). Consequently this chart is diagrammatic only.

I. BATTLE CRUISER ACTION(1) 3.30 P.M. Beatty sights Hipper.

(2) 3.48 P.M. Battle cruisers engage at 18,500 yds., “both forces opening fire practically simultaneously.”

(3) 4.06 P.M. Indefatigable sunk.

(4) 4.42 P.M. Beatty sights High Seas Fleet, and turns north (column right about).

(5) 4.57 P.M. Evan-Thomas turns north, covering Beatty.

(6) 5.35 P.M. Beatty’s force, pursued by German battle cruisers and High Seas Fleet, on northerly course at long range.

II. MAIN ENGAGEMENT(7) 5.56 P.M. Beatty sights Jellicoe and shifts to easterly course at utmost speed.

(8) 6.20–7.00 P.M. Jellicoe deploys on port wing column (deployment “complete” at 6.38). Beatty takes position ahead of Grand Fleet. Hood takes station ahead of Beatty. Evan-Thomas falls in astern of Grand Fleet.

Scheer turns whole German Fleet to west (ships right about) at 6.35, covered by smoke screens. Scheer repeats the turn of the whole fleet (ships right about) to east at 6.55.

(9) 7.17 P.M. Scheer for the third time makes “swing-around” of whole German Fleet (ships right about) to southwest, under cover of smoke screens and destroyer attacks. Jellicoe turns away to avoid torpedoes (7.23).

(10) 8.00 P.M.

(11) 8.30–9.00 P.M. Jellicoe disposes for the night.

1

“In accordance with instructions contained in their Lordship’s telegram, No. 434, of 30th May, code time 1740, the Grand Fleet proceeded to sea on 30th May, 1916.” (J)

2

See Table II.

3

It was nearly two hours before Vice Admiral Hipper could get on board the Moltke.

4

Lord Jellicoe had sent to the Admiralty a formal dispatch (October 30, 1914) stating his conviction that the Germans would “rely to a great extent on submarines, mines and torpedoes,” (J) and defining his own “tactical methods in relation to these forms of attack.” (J) On November 7, 1914, the Admiralty approved the “views stated therein.” Lord Jellicoe in his book cites this Admiralty approval of 1914 as applying to the Battle of Jutland.

5

“The German organization at night is very good. Their system of recognition signals is excellent. Ours are practically nil. Their searchlights are superior to ours, and they use them with great effect. Finally, their method of firing at night gives excellent results. I am reluctantly of the opinion that under night conditions we have a good deal to learn from them.” (J)

6

“The British Fleet was not properly equipped for fighting an action at night. The German fleet was. Consequently to fight them at night would only have been to court disaster. Lord Jellicoe’s business was to preserve the Grand Fleet, the main defense of the Empire as well as of the Allied cause, not to risk its existence.” Sir Percy Scott, Fifty Years in the Royal Navy.

7

See A Guide to the Military History of The World War, pp. 320–22.

8

“Jellicoe was sending out radio instructions at the rate of two a minute – while von Scheer made only nine such signals during the whole battle. This I learn on credible testimony.” Rear Admiral Caspar F. Goodrich, U.S.N.

9

The Pommern was sunk in the night after the action of fleets had been broken off.