полная версия

полная версияLetters from Switzerland and Travels in Italy

It seemed strange to me that they carry on this exercise by an old lime-wall, without the slightest convenience for spectators; why is it not done in the amphitheatre, where there would be such ample room?

Verona, September 17.

What I have seen of pictures I will but briefly touch upon, and add some remarks. I do not make this extraordinary tour for the sake of deceiving myself, but to become acquainted with myself by means of these objects. I therefore honestly confess that of the painter's art – of his manipulation, I understand but little. My attention, and observation, can only be directed to the practical part, to the subject, and the general treatment of it.

Verona

S. Georgio is a gallery of good pictures, all altar-pieces, and all remarkable, if not of equal value. But what subjects were the hapless artists obliged to paint? And for whom? Perhaps a shower of manna thirty feet long, and twenty feet high, with the miracle of the loaves as a companion. What could be made of these subjects? Hungry men falling on little grains, and a countless multitude of others, to whom bread is handed. The artists have racked their invention in order to get something striking out of such wretched subjects. And yet, stimulated by the urgency of the case, genius has produced some beautiful things. An artist, who had to paint S. Ursula with the eleven thousand virgins, has got over the difficulty cleverly enough. The saint stands in the foreground, as if she had conquered the country. She is very noble, like an Amazonia's virgin, and without any enticing charms; on the other hand, her troop is shown descending from the ships, and moving in procession at a diminishing distance. The Assumption of the Virgin, by Titian, in the dome, has become much blackened, and it is a thought worthy of praise that, at the moment of her apotheosis, she looks not towards heaven, but towards her friends below.

In the Gherardini Gallery I found some very fine things by Orbitto, and for the first time became acquainted with this meritorious artist. At a distance we only hear of the first artists, and then we are often contented with names only; but when we draw nearer to this starry sky, and the luminaries of the second and third magnitude also begin to twinkle, each one coming forward and occupying his proper place in the whole constellation, then the world becomes wide, and art becomes rich. I must here commend the conception of one of the pictures. Sampson has gone to sleep in the lap of Dalilah, and she has softly stretched her hand over him to reach a pair of scissors, which lies near the lamp on the table. The execution is admirable. In the Canopa Palace I observed a Danäe.

The Bevilagua Palace contains the most valuable things. A picture by Tintoretto, which is called a "Paradise," but which, in fact, represents the Coronation of the Virgin Mary as Queen of Heaven, in the presence of all the patriarchs, prophets, apostles, saints, angels, &c., affords an opportunity for displaying all the riches of the most felicitous genius. To admire and enjoy all that care of manipulation, that spirit and variety of expression, it is necessary to possess the picture, and to have it before one all one's life. The painter's work is carried on ad infinitum,; even the farthest angels' heads, which are vanishing in the halo, preserve something of character. The largest figures may be about a foot high; Mary, and the Christ who is crowning her, about four inches. Eve is, however, the finest woman in the picture; a little voluptuous, as from time immemorial.

A couple of portraits by Paul Veronese have only increased my veneration for that artist. The collection of antiquities is very fine; there is a son of Niobe extended in death, which is highly valuable; and the busts, including an Augustus with the civic crown, a Caligula, and others, are mostly of great interest, notwithstanding the restoration of the noses.

It lies in my nature to admire, willingly and joyfully, all that is great and beautiful, and the cultivation of this talent, day after day, hour after hour, by the inspection of such beautiful objects, produces the happiest feelings.

Verona

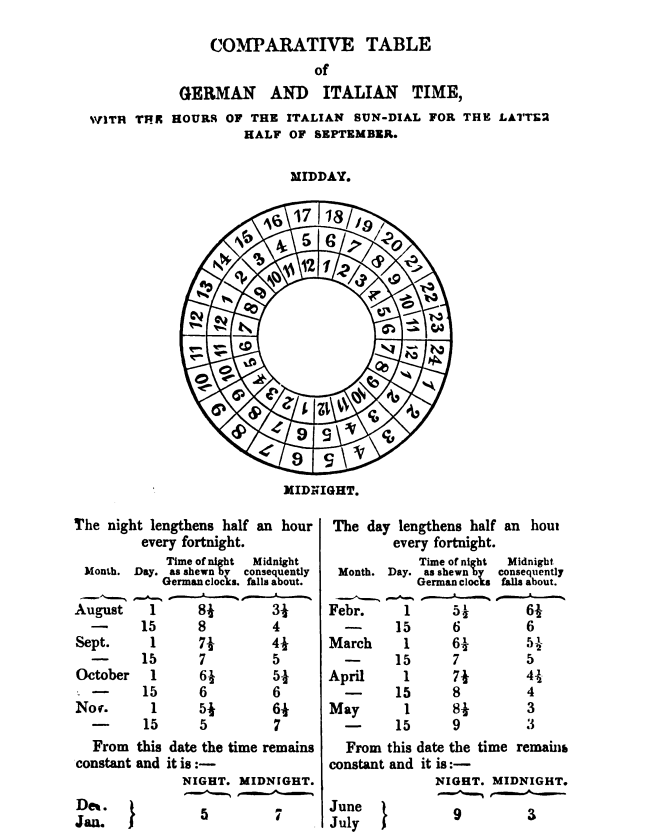

In a land, where we enjoy the days but take especial delight in the evenings, the time of nightfall is highly important. For now work ceases; those who have gone out walking turn back; the father wishes to have his daughter home again; the day has an end. What the day is we Cimmerians hardly know. In our eternal mist and fog it is the same thing to us, whether it be day or night, for how much time can we really pass and enjoy in the open air? Now, when night sets in, the day, which consisted of a morning and an evening, is decidedly past, four and twenty hours are gone, the bells ring, the rosary is taken in hand, and the maid, entering the chamber with the lighted lamp, says, "felicissima notte." This epoch varies with every season, and a man who lives here in actual life cannot go wrong, because all the enjoyments of his existence are regulated not by the nominal hour, but by the time of day. If the people were forced to use a German clock they would be perplexed, for their own is intimately connected with their nature. About an hour and a half, or an hour before midnight, the nobility begin to ride out. They proceed to the Piazza della Bra, along the long, broad street to the Porta Nuova out at the gate, and along the city, and when night sets in, they all return home. Sometimes they go to the churches to say their Ave Maria della sera: sometimes they keep on the Bra, where the cavaliers step up to the coaches and converse for a while with the ladies. The foot passengers remain till a late hour of night, but I have never stopped till the last. To-day just enough rain had fallen to lay the dust, and the spectacle was most cheerful and animated.

That I may accommodate myself the better to the custom of the country I have devised a plan for mastering more easily the Italian method of reckoning the hours. The accompanying diagram may give an idea of it. The inner circle denotes our four and twenty hours, from midnight to midnight, divided into twice twelve, as we reckon, and as our clocks indicate. The middle circle shows how the clocks strike at the present season, namely, as much as twelve twice in the twenty-four hours, but in such a way that it strikes one, when it strikes eight with us, and so on till the number twelve is complete. At eight o'clock in the morning according to our clock it again strikes one, and so on. Finally the outer circle shows how the four and twenty hours are reckoned in actual life. For example, I hear seven o'clock striking in the night, and know that midnight is at five o'clock; I therefore deduct the latter number from the former, and thus have two hours after midnight. If I hear seven o'clock strike in the day-time, and know that noon is at five, I proceed in the same way, and thus have two in the afternoon. But if I wish to express the hour according to the fashion of this country, I must know that noon is seventeen o'clock; I add the two, and get nineteen o'clock. When this method is heard and thought of for the first time, it seems extremely confused and difficult to manage, but we soon grow accustomed to it and find the occupation amusing. The people themselves take delight in this perpetual calculation, just as children are pleased with easily surmounted difficulties. Indeed they always have their fingers in the air, make any calculation in their heads, and like to occupy themselves with figures. Besides to the inhabitant of the country the matter is so much the easier, as he really does not trouble himself about noon and midnight, and does not, like the foreign resident, compare two clocks with each other. They only count from the evening the hours, as they strike, and in the day-time they add the number to the varying number of noon, with which they are acquainted. The rest is explained by the remarks appended to the diagram: —

Verona, Sept. 17.

The people here jostle one another actively enough; the narrow streets, where shops and workmen's stalls are thickly crowded together, have a particularly cheerful look. There is no such thing as a door in front of the shop or workroom; the whole breadth of the house is open, and one may see all that passes in the interior. Half-way out into the path, the tailors are sewing; and the cobblers are pulling and rapping; indeed the work-stalls make a part of the street. In the evening, when the lights are burning, the appearance is most lively.

The squares are very full on market days; there are fruit and vegetables without number, and garlic and onions to the heart's desire. Then again throughout the day there is a ceaseless screaming, bantering, singing, squalling, huzzaing, and laughing. The mildness of the air, and the cheapness of the food, make subsistence easy. Everything possible is done in the open air.

At night singing and all sorts of noises begin. The ballad of "Marlbrook" is heard in every street; – then comes a dulcimer, then a violin. They try to imitate all the birds with a pipe. The strangest sounds are heard on every side. A mild climate can give this exquisite enjoyment of mere existence, even to poverty, and the very shadow of the people seems respectable.

The want of cleanliness and convenience, which so much strikes us in the houses, arises from the following cause: – the inhabitants are always out of doors, and in their light-heartedness think of nothing. With the people all goes right, even the middle-class man just lives on from day to day, while the rich and genteel shut themselves up in their dwellings, which are not so habitable as in the north. Society is found in the open streets. Fore-courts and colonnades are all soiled with filth, for things are done in the most natural manner. The people always feel their way before them. The rich man may be rich, and build his palaces; and the nobile may rule, but if he makes a colonnade or a fore-court, the people will make use of it for their own occasions, and have no more urgent wish than to get rid as soon as possible, of that which they have taken as often as possible. If a person cannot bear this, he must not play the great gentleman, that is to say, he must act as if a part of his dwelling belonged to the public. He may shut his door, and all will be right. But in open buildings the people are not to be debarred of their privileges, and this, throughout Italy, is a nuisance to the foreigner.

To-day I remarked in several streets of the town, the customs and manners of the middle-classes especially, who appear very numerous and busy. They swing their arms as they walk. Persons of a high rank, who on certain occasions wear a sword, swing only one arm, being accustomed to hold the left arm still.

Although the people are careless enough with respect to their own wants and occupations, they have a keen eye for everything foreign. Thus in the very first days, I observed that every one took notice of my boots, because here they are too expensive an article of dress to wear even in winter. Now I wear shoes and stockings nobody looks at me. Particularly I noticed this morning, when all were running about with flowers, vegetables, garlic, and other market-stuff, that a twig of cypress, which I carried in my hand, did not escape them. Some green cones hung upon it, and I held in the same hand some blooming caper-twigs. Everybody, large and small, watched me closely, and seemed to entertain some whimsical thought.

Verona-Vicenza

I brought these twigs from the Giusti garden, which is finely situated, and in which there are monstrous cypresses, all pointed up like spikes into the air. The Taxus, which in northern gardening we find cut to a sharp point, is probably an imitation of this splendid natural product. A tree, the branches of which, the oldest as well as the youngest, are striving to reach heaven, – a tree which will last its three hundred years, is well worthy of veneration. Judging from the time when this garden was laid out, these trees have already attained that advanced age.

Vicenza, Sept. 19.

The way from Verona hither is very pleasant: we go north-eastwards along the mountains, always keeping to the left the foremost mountains, which consist of sand, lime, clay, and marl; the hills which they form, are dotted with villages, castles, and houses. To the right extends the broad plain, along which the road goes. The straight broad path, which is in good preservation, goes through a fertile field; we look into deep avenues of trees, up which the vines are trained to a considerable height, and then drop down, like pendant branches. Here we can get an admirable idea of festoons! The grapes are ripe, and are heavy on the tendrils, which hang down long and trembling. The road is filled with people of every class and occupation, and I was particularly pleased by some carts, with low solid wheels, which, with teams of fine oxen, carry the large vats, in which the grapes from the vineyards are put and pressed. The drivers rode in them when they were empty, and the whole was like a triumphal procession of Bacchanals. Between the ranks of vines the ground is used for all sorts of grain, especially Indian corn and millet (Sörgel).

As one goes towards Vicenza, the hills again rise from north to south and enclose the plain; they are, it is said, volcanic. Vicenza lies at their foot, or if you will, in a bosom which they form.

Vicenza, Sept. 19.

Though I have been here only a few hours, I have already run through the town, and seen the Olympian theatre, and the buildings of Palladio. A very pretty little book is published here, for the convenience of foreigners, with copper-plates and some letter-press, that shows knowledge of art. When once one stands in the presence of these works, one immediately perceives their great value, for they are calculated to fill the eye with their actual greatness and massiveness, and to satisfy the mind by the beautiful harmony of their dimensions, not only in abstract sketches, but with all the prominences and distances of perspective. Therefore I say of Palladio: he was a man really and intrinsically great, whose greatness was outwardly manifested. The chief difficulty with which this man, like all modern architects, had to struggle, was the suitable application of the orders of columns to buildings for domestic or public use; for there is always a contradiction in the combination of columns and walls. But with what success has he not worked them up together! What an imposing effect has the aspect of his edifices: at the sight of them one almost forgets that he is attempting to reconcile us to a violation of the rules of his art. There is, indeed, something divine about his designs, which may be exactly compared to the creations of the great poet, who, out of truth and falsehood elaborates something between both, and charms us with its borrowed existence.

Vicenza

The Olympic theatre is a theatre of the ancients, realized on a small scale, and indescribably beautiful. However, compared with our theatres, it reminds me of a genteel, rich, well-bred child, contrasted with a shrewd man of the world, who, though he is neither so rich, nor so genteel, and well-bred, knows better how to employ his resources.

If we contemplate, on the spot, the noble buildings which Palladio has erected, and see how they are disfigured by the mean filthy necessities of the people, how the plans of most of them exceeded the means of those who undertook them, and how little these precious monuments of one lofty mind are adapted to all else around, the thought occurs, that it is just the same with everything else; for we receive but little thanks from men, when we would elevate their internal aspirations, give them a great idea of themselves, and make them feel the grandeur of a really noble existence. But when one cajoles them, tells them tales, and helping them on from day to day, makes them worse, then one is just the man they like; and hence it is that modern times take delight in so many absurdities. I do not say this to lower my friends, I only say that they are so, and that people must not be astonished to find everything just as it is.

How the Basilica of Palladio looks by the side of an old castellated kind of a building, dotted all over with windows of different sizes (whose removal, tower and all, the artist evidently contemplated), – it is impossible to describe – and besides I must now, by a strange effort, compress my own feelings, for, I too, alas! find here side by side both what I seek and what I fly from.

Sept. 20.

Yesterday we had the opera, which lasted till midnight, and I was glad to get some rest. The three Sultanesses and the Rape of the Seraglio have afforded several tatters, out of which the piece has been patched up, with very little skill. The music is agreeable to the ear, but is probably by an amateur; for not a single thought struck me as being new. The ballets, on the other hand, were charming. The principle pair of dancers executed an Allemande to perfection.

The theatre is new, pleasant, beautiful, modestly magnificent, uniform throughout, just as it ought to be in a provincial town. Every box has hangings of the same color, and the one belonging to the Capitan Grande, is only distinguished from the rest, by the fact that the hangings are somewhat longer.

The prima donna, who is a great favorite of the whole people, is tremendously applauded, on her entrance, and the "gods" are quite obstreperous with their delight, when she does anything remarkably well, which very often happens. Her manners are natural, she has a pretty figure, a fine voice, a pleasing countenance, and, above all, a really modest demeanour, while there might be more grace in the arms. However, I am not what I was, I feel that I am spoiled, I am spoiled for a "god."

Sept. 21.

To-day I visited Dr. Tura. Five years ago he passionately devoted himself to the study of plants, formed a herbarium of the Italian flora, and laid out a botanical garden under the superintendence of the former bishop. However, all that has come to an end. Medical practice drove away natural history, the herbarium is eaten by worms, the bishop is dead, and the botanic garden is again rationally planted with cabbages and garlic.

Dr. Tura is a very refined and good man. He told me his history with frankness, purity of mind, and modesty, and altogether spoke in a very definite and affable manner. At the same time he did not like to open his cabinets, which perhaps were in no very presentable condition. Our conversation soon came to a stand-still.

Sept. 21. Evening.

I called upon the old architect Scamozzi, who has published an edition of Palladio's buildings, and is a diligent artist, passionately devoted to his art. He gave me some directions, being delighted with my sympathy. Among Palladio's buildings there is one, for which I always had an especial predilection, and which is said to have been his own residence When it is seen close, there is far more in it than appears in a picture. I should have liked to draw it, and to illuminate it with colors, to show the material and the age. It must not, however, be imagined that the architect has built himself a palace. The house is the most modest in the world, with only two windows, separated from each other by a broad space, which would admit a third. If it were imitated in a picture, which should exhibit the neighbouring houses at the same time, the spectator would be pleased to observe how it has been let in between them. Canaletto was the man who should have painted it.

Vicenza

To-day I visited the splendid building which stands on a pleasant elevation about half a league from the town, and is called the "Rotonda." It is a quadrangular building, enclosing a circular hall, lighted from the top. On all the four sides, you ascend a broad flight of steps, and always come to a vestibule, which is formed of six Corinthian columns. Probably the luxury of architecture was never carried to so high a point. The space occupied by the steps and vestibules is much larger than that occupied by the house itself; for every one of the sides is as grand and pleasing as the front of a temple. With respect to the inside it may be called habitable, but not comfortable. The hall is of the finest proportions, and so are the chambers; but they would hardly suffice for the actual wants of any genteel family in a summer-residence. On the other hand it presents a most beautiful appearance, as it is viewed on every side throughout the district. The variety which is produced by the principal mass, as, together with the projecting columns, it is gradually brought before the eyes of the spectator who walks round it, is very great; and the purpose of the owner, who wished to leave a large trust-estate, and at the same time a visible monument of his wealth, is completely obtained. And while the building appears in all its magnificence, when viewed from any spot in the district, it also forms the point of view for a most agreeable prospect. You may see the Bachiglione flowing along, and taking vessels down from Verona to the Brenta, while you overlook the extensive possessions which the Marquis Capra wished to preserve undivided in his family. The inscriptions on the four gable-ends, which together constitute one whole, are worthy to be noted down:

Marcus Capra Gabrielis filiusQui ædes has Arctissimoprimogenituræ gradui subjecitUna cum omnibusCensibus agrisvallibus et collibusCitra viam magnamMemorise perpetuæ mandans hæcDum sustinet ac abstinet.The conclusion in particular is strange enough. A man who has at command so much wealth and such a capacious will, still feels that he must bear and forbear. This can be learned at a less expense.

Sept. 22.

This evening I was at a meeting held by the academy of the "Olympians." It is mere play-work, but good in its way, and seems to keep up a little spice and life among the people. There is the great hall by Palladio's theatre, handsomely lighted up; the Capitan and a portion of the nobility are present, besides a public composed of educated persons, and several of the clergy; the whole assembly amounting to about five hundred.

The question proposed by the president for to-day's sitting was this: "Which has been most serviceable to the fine arts, invention or imitation?" This was a happy notion, for if the alternatives which are involved in the question are kept duly apart, one may go on debating for centuries. The academicians have gallantly availed themselves of the occasion, and have produced all sorts of things in prose and verse, – some very good.

Then there is the liveliest public. The audience cry bravo, and clap their hands and laugh. What a thing it is to stand thus before one's nation, and amuse them in person! We must set down our best productions in black and white; every one squats down with them in a corner, and scribbles at them as he can.

Vicenza

It may be imagined that even on this occasion Palladio would be continually appealed to, whether the discourse was in favour of invention or imitation. At the end, which is always the right place for a joke, one of the speakers hit on a happy thought, and said that the others had already taken Palladio away from him, so that he, for his part, would praise Franceschini, the great silk-manufacturer. He then began to show the advantages which this enterprising man, and through him the city of Vicenza, had derived from imitating the Lyonnese and Florentine stuffs, and thence came to the conclusion that imitation stands far above invention. This was done with so much humour, that uninterrupted laughter was excited. Generally those who spoke in favor of imitation obtained the most applause, for they said nothing but what was adapted to the thoughts and capacities of the multitude. Once the public, by a violent clapping of hands, gave its hearty approval to a most clumsy sophism, when it had not felt many good – nay, excellent things, that had been said in honour of invention. I am very glad I have witnessed this scene, for it is highly gratifying to see Palladio, after the lapse of so long a time, still honoured by his fellow-citizens, as their polar-star and model.