полная версия

полная версияSt. Paul's Epistle to the Ephesians: A Practical Exposition

It is then in view of unseen but personal spiritual adversaries organized against us as armies, under leaders who have at their control wide-reaching social forces of evil, and who intrude themselves into the highest spiritual regions 'the heavenly places' to which in their own nature they belong, that St. Paul would have us equip ourselves for fighting in 'the armour of light[213].'

If there is a spiritual battle, armour defensive and offensive becomes a natural metaphor which St. Paul frequently uses[214]. But in his imprisonment he must have become specially habituated to the armour of Roman soldiers, and here, as it were, he makes a spiritual meditation on the pieces of the 'panoply' which were continually under his observation.

We are, then, to 'take up' or 'put on' the panoply or whole armour of God. This means more than the armour which God supplies. It is probably like 'the righteousness of God,' something which is not only a gift of God, but a gift of His own self. Our righteousness is Christ, and He is our armour. Christ, the 'stronger man,' who overthrew 'the strong man armed' in His own person[215], and 'took away from him his panoply in which he trusted,' is to be our defence. And by no external protection; we are to clothe ourselves in His nature, to put Him on as our armour. His is the strength in which we are, like Him, to come triumphant through the hour of darkness.

Now the parts of the armour, the elements of Christ's unconquerable moral strength, what are they?

The belt which keeps all else in its place is for the Christian, truth – that is, singleness of eye or perfect sincerity – the pure and simple desire of the light. 'Unless the vessel be clean (or sincere)' said the old Roman proverb, 'whatever you put into it turns sour.' A lack of sincerity at the heart of the spiritual life will destroy it all. Then the breastplate which covers vital organs is, for the Christian, righteousness – the specific righteousness of Christ, St. Paul seems to imply[216], in which in its indivisible unity he is to enwrap himself. And, as the feet of the soldier must be well shod not only for protection but also to facilitate free movement on all sorts of ground, the Christian too is to be so possessed with the good tidings of peace that he is 'prepared' to move and act under all circumstances – all hesitations, and delays, and uncertainties which hinder movement gone – his feet shod with the preparedness which belongs to those who have peace at the heart. ('How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of him that bringeth glad tidings, that publisheth peace.') In these three fundamental dispositions – single-mindedness, whole-hearted following of Christ, readiness such as belongs to a believer in the good tidings – lies the Christian's strength. But the armour is not yet complete. The attacks of the enemy upon the thoughts will be frequent and fiery. A constant and rapid action of the will will be necessary to protect ourselves from evil suggestions lest they obtain a lodgement. And the method of self-protection is to look continually and deliberately out of ourselves up to Christ – to appeal to Him, to invoke His name, to draw upon His strength by acts of our will. Thus faith, continually at every fresh assault looking instinctively to Christ and drawing upon His help, is to be our shield, off which the enemy's darts will glance harmless, their hurtful fire quenched. And in thus defending ourselves we must have continually in mind that God has delivered man by a great redemption[217]. It is the sense of this great salvation, the conviction of each Christian that he is among those who have been saved and are tasting this salvation, which is to cover his head from attack like a helmet[218]. And God's word – God's specific and particular utterances, through inspired prophets and psalmists – is to equip his mouth with a sword of power; as in His temptation and on the cross, Christ 'put off from Himself the principalities and powers, and made a show of them, triumphing over them openly' by the words of Holy Scripture; as Bunyan's Christian, when 'Apollyon was fetching him his last blow, nimbly stretched out his hand and caught' for his 'sword' the word of Micah, 'when I fall I shall arise.' This is one fruit of constant meditation on the words of Holy Scripture, that they recur to our minds when we most need them. And then St. Paul passes from metaphor to simple speech, and for the last weapon bids the Christians use 'always' that most powerful of all spiritual weapons for themselves and others, 'prayer and supplication' of all kinds and 'in all seasons.' But it is not to be ignorant and blind prayer; it is to be prayer 'in the spirit,' 'who helpeth our infirmities, for we know not of ourselves how to pray as we ought.' 'The things of God none knoweth, save the Spirit of God'[219]; and it is to be the sort of prayer about which trouble is taken, and which is persevering; and it is to be prayer for others as well as for themselves, 'for all the saints.' And St. Paul uses the pastor's privilege, and asks for himself the support of his converts' prayers, that he may have both power of speech and courage to proclaim the good tidings of the divine secret disclosed, for which he is already suffering as a prisoner.

Finally, be strong in the Lord, and in the strength of his might. Put on the whole armour of God, that ye may be able to stand against the wiles of the devil. For our wrestling is not against flesh and blood, but against the principalities, against the powers, against the world-rulers of this darkness, against the spiritual hosts of wickedness in the heavenly places. Wherefore take up the whole armour of God, that ye may be able to withstand in the evil day, and, having done all, to stand. Stand therefore, having girded your loins with truth, and having put on the breastplate of righteousness, and having shod your feet with the preparation of the gospel of peace; withal taking up the shield of faith, wherewith ye shall be able to quench all the fiery darts of the evil one. And take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God: with all prayer and supplication praying at all seasons in the Spirit, and watching thereunto in all perseverance and supplication for all the saints, and on my behalf, that utterance may be given unto me in opening my mouth, to make known with boldness the mystery of the gospel, for which I am an ambassador in chains; that in it I may speak boldly, as I ought to speak.

St. Paul does not only exhort Christians to pray, but he gives them abundant examples. In this epistle there are two specimens[220] of prayer for the spiritual progress of his converts, mingled with thanksgivings and praise. We habitually pray for others that they may be delivered from temporal evils, or that they may be converted from flagrant sin or unbelief. But surely we very seldom pray rich prayers, like those of St. Paul's, for others' progress in spiritual apprehension.

CONCLUSION. CHAPTER VI. 21-24

Conclusion

But that ye also may know my affairs, how I do, Tychicus, the beloved brother and faithful minister in the Lord, shall make known to you all things: whom I have sent unto you for this very purpose, that ye may know our state, and that he may comfort your hearts. Peace be to the brethren, and love with faith, from God the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. Grace be with all them that love our Lord Jesus Christ in uncorruptness.

Tychicus was a native of Asia Minor[221], a companion and delegate of St. Paul, like Timothy and others[222]. He was entrusted with the task presumably of conveying this letter to the churches of Asia Minor, and certainly of informing them as to the apostle's state in his Roman imprisonment – information which could not fail to comfort and encourage them.

St. Paul brings this wonderful letter to a conclusion with a brief benediction to the brethren – an invocation upon them of divine peace, and love with faith – an invocation of divine favour upon all that 'love our Lord Jesus Christ in uncorruptness.' Corruption is the fruit of sin, the condition of the 'old man[223].' Incorruption is the state of the risen Christ, and in Him the members of His body are to be preserved, and at last raised 'incorruptible[224]' in body. But there is a prior 'incorruptibleness' of spirit in which all Christians are to live from the first[225], a freedom from all such doublemindedness or uncleanness as can corrupt the central life of the man. And to love Christ with this incorruptibility is the condition of the permanent enjoyment of all that His good favour would bestow upon us.

APPENDED NOTES

NOTE A. See p. 26

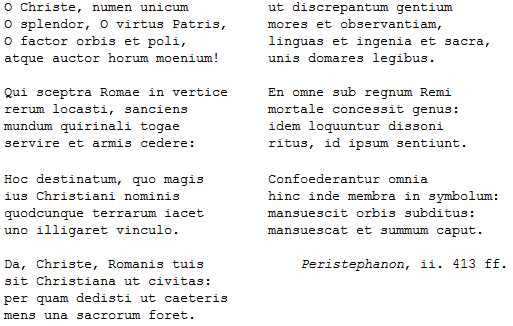

THE ROMAN EMPIRE RECOGNIZED BY CHRISTIANWRITERS AS A DIVINE PREPARATION FORTHE SPREAD OF THE GOSPEL(1) The Spanish poet Prudentius (c. A.D. 400) fully appreciates the influence of the Roman Empire in welding together the world into a unity of government, laws, language, customs, and religious rites, to prepare the way for the universal Church. The stanzas are remarkable and worth quoting. They are put as a prayer into the mouth of the Roman deacon Laurence during his martyrdom. He recognizes what the Roman Empire has done, and prays that Rome may follow the example of the rest of the world in becoming Christian.

(2) The Pope, Leo the Great (c. A.D. 450), speaks thus (Serm. lxxxii. 2): 'That the result of this unspeakable grace (the Incarnation) might be spread abroad throughout the world, God's providence made ready the Roman Empire, whose growth has reached so far that the whole multitude of nations have been brought into neighbourhood and connexion. For it particularly suited the divinely planned work that many kingdoms should be leagued together in one empire, so that the universal preaching might make its way quickly through nations already united under the government of one state. And yet that state, in ignorance of the author of its aggrandisement, though it ruled almost all races, was enthralled by the errors of them all; and seemed to itself to have received a great religion, because it had rejected no falsehood. And for this very reason its emancipation through Christ was the more wondrous that it had been so fast bound by Satan.' Leo further recognizes that the Popes are entering into the position of the Caesars (c. 1), that Rome, 'made the head of the world by being the holy see of blessed Peter, should rule more widely by means of the divine religion than of earthly sovereignty.' But his statement of the relation of Peter to Paul in the evangelization of the world (c. 5) is remarkably unhistorical.

NOTE B. See p. 29

THE (SO-CALLED) 'LETTERS OF HERACLEITUS.'Nine letters under the name of the great philosopher of Ephesus remain to us. In one of them (iv) Heracleitus is represented as saying to some Ephesian adversaries, 'If you had been able to live again by a new birth 500 years hence, you would have discovered Heracleitus yet alive [i.e. in the memory of men] but not so much as a trace of your name.' This probably indicates that the author is writing 500 years after Heracleitus' supposed age. His age was differently estimated. But '500 years after Heracleitus' would mean, according to all reckonings, about the first half of the first century A.D. All the other indications of age in the letters agree with this. (See Jacob Bernays' Heraclitischen Briefe, Berlin, 1869, p. 112.) They were written presumably at Ephesus, and all or most of them by a Stoic philosopher. I do not think that it is necessary to assume traces of Jewish influence in these letters, any more than in the writings of Seneca. And the bulk of the letters is so thoroughly Stoic and contrary to Jewish feeling, that a Jew is hardly likely to have interpolated them. They illustrate therefore the current philosophic ideas which were at work in the world in which St. Paul lived and taught, when he was outside Judaea. That St. Paul was familiar with these ideas, however his familiarity may have been gained, is shown beyond possibility of mistake by his speeches – supposing them substantially genuine – at Lystra and Athens.

The following passages in these letters are interesting:

(1) (From Heracleitus' defence of himself against a charge of impiety in letter iv) 'Where is God? Is he shut up in the temples? You forsooth are pious who set up the God in a dark place. A man takes it for an insult if he is said to be "made of stone": and is God truly described as "born of the rocks"? Ignorant men, do ye not know that God is not fashioned with hands, nor can you make him a sufficient pedestal, nor shut him into one enclosure, but the whole world is his temple, decorated with animals and planets and stars? I inscribed my altar "to Heracles the Ephesian" [Greek: ERAKLEI TOI EPHESIOI] making the God your citizen, not – he continues – to myself "Heracleitus an Ephesian" [the same letters differently divided], as I am accused of doing by you in your ignorance. Yet Heracles was a man deified by his goodness and noble deeds; and were his virtues and labours greater than mine? I have conquered money and ambition: I have mastered fear and flattery,' &c. Then after a passage about the certainty of his own immortal renown, he returns to ridicule idolatry. 'If an altar of a god be not set up, is there no god? or if an altar be set up to what is not a god, is it a god – so that stones become the evidences (witnesses) of Gods? Nay it is his works which shall bear witness to God, as the sun, the day and night, the seasons, the whole fruitful earth, and the circle of the moon, his work and witness in the heavens.' The whole of this letter (iv), which can be paralleled in all its ideas from Stoic and Platonic sources, may compare and contrast with Acts xiv. 15-18; xvii. 22-29.

(2) Letter v is written by Heracleitus in sickness. He gives a theory of disease as an excess of some element in the body; and describes his soul as a divine thing reproducing in his body the healing activity of God in the world as a whole, – 'imitating God' by knowledge of the method of nature. Even if his body prove unmanageable and succumb to fate, yet his soul will rise to heaven and 'I shall have my citizenship (Greek: politeúsouai) not among men but among Gods.' 'Perhaps my soul is giving prophetic intimation of its release even now from its prison house' so short lived and worthless. Letter vi is a continuation of v, containing a denunciation of contemporary medicine on the ground of its lack of science, and a further explanation of the Stoic doctrine of the immanence of God in all nature – forming, ordering, dissolving, transforming, healing everywhere. 'Him will I imitate in myself and dismiss all others.' We should compare and (even more) contrast St. Paul's assertions of independence of bodily circumstances; his belief in the higher sense of 'nature' (Rom. ii. 14), and such phrases as Phil. ii. 20, 'our citizenship is in heaven,' Eph. v. 1, 'Be ye imitators of God.'

(3) Letter vii is addressed to Hermodorus in exile. Heracleitus is to be exiled also 'for misanthropy and refusal to smile' by a law directed against him alone. After an interesting condemnation of privilegia, the letter explains his misanthropy. He does not hate men, but their vices. The law should run 'If any man hates vice let him leave the city.' Then he will go willingly. In fact he is already an exile while in the city, for he cannot share its vices. Then he describes Ephesian life in terms of fierce contempt, their lusts natural and unnatural, their frauds, their wars of words, their legal contentiousness, their faithlessness and perjuries, their robberies of temples. He denounces their vices in connexion with the worship of Cybele (beating the kettle-drum) and Dionysus (the eating of live flesh), and with religious vigils and banquets, and alludes to details of sensuality associated with these meetings. He condemns the submission of great principles to the verdicts of the crowd at their theatres, and passes to a further vivid onslaught on their quarrels and murders (they are no longer men but beasts), on their use of music to excite their bloodthirsty passions, and on war altogether as contrary to 'the law of nature,' and involving the pursuit of all sorts of vice. All this impeachment may be compared with St. Paul, who speaks however by comparison with marked reserve, in Rom. i. 24-31, Eph. iv. 17-19, and elsewhere.

(4) The eighth letter is again written to Hermodorus now on his way to Italy to assist the Decemvirs with the Ten Tables. It contains a somewhat remarkable 'judgement on wealthy Ephesus' and statement of the judicial function of wealth. 'God does not punish by taking wealth away, but rather gives it to the wicked, that through having opportunity to sin they may be convicted, and by the very abundance of their resources may exhibit their corruption on a wider stage.' Cf. 1 Tim. vi. 9.

(5) The banishment of Hermodorus had been on account of a proposed law to grant equal citizenship to freed men, and the right of public office to their children. This instance of Ephesian intolerance gives occasion for an enunciation of the Stoic doctrine that the only real freedom is moral freedom, and moral freedom constitutes a man a citizen of the world. 'The good Ephesian is a citizen of the world. For this is the common home of all, and its law is no written document but God (Greek: ou grámma alla theós), and he who transgresses his duty shall be impious; or rather he will not dare to transgress, for he will not escape justice.' 'Let the Ephesians cease to be the sort of men they are, and they will love all men in an equality of virtue.' 'Virtue, not the chance of birth, makes men equal.' 'Only vice enslaves, only virtue liberates.' For men to enslave their fellow men is to fall below the beasts; so also to mutilate them as the Ephesians do their Megabyzi – the eunuch-priests of the wooden image of Artemis. There must be inequality of function in the world, but not refusal of fellowship, as the higher parts of nature do not despise the lower, or the soul think scorn to dwell with the body, or the head despise the entrails, or God refuse to give the gifts of nature, such as the light of the sun, to all equally. Here again we have what is both like and unlike St. Paul's doctrine of true human liberty and 'fellowship in the body.'

On the whole I think these letters are worth more notice than they have received, both in themselves and as a good example of the sort of religious and moral doctrine current in the better heathen circles of the Asiatic cities, while St. Paul was teaching. It presents many points of connexion with St. Paul's teaching, and co-operated with the influence of the Jewish synagogue to prepare men's minds for it. But perhaps what chiefly strikes us is the contrast which the fierce and arrogant contempt of the Stoic presents to the loving hopefulness of the Christian messenger of the gospel.

NOTE C. See p. 74

THE JEWISH DOCTRINE OF WORKS IN THE APOCALYPSE OF BARUCHMr. R. H. Charles gives us the following statement[226]: —

'The Talmudic doctrine of works may be shortly summarized as follows: Every good work – whether the fulfilment of a command or an act of mercy – established a certain degree of merit with God, while every evil work entailed a corresponding demerit. A man's position with God depended on the relation existing between his merits and demerits, and his salvation on the preponderance of the former over the latter. The relation between his merits and demerits was determined daily by the weighing of his deeds. But as the results of such judgements were necessarily unknown, there could not fail to be much uneasiness; and, to allay this, the doctrine of the vicarious righteousness of the patriarchs and saints of Israel was developed not later than the beginning of the Christian era (cf. Matt. iii. 9). A man could thereby summon to his aid the merits of the fathers, and so counterbalance his demerits.

'It is obvious that such a system does not admit of forgiveness in any spiritual sense of the term. It can only mean in such a connexion a remission of penalty to the offender, on the ground that compensation is furnished, either through his own merit or through that of the righteous fathers. Thus, as Weber vigorously puts it: "Vergebung ohne Bezahlung gibt es nicht." Thus, according to popular Pharisaism, God never remitted a debt until He was paid in full, and so long as it was paid it mattered not by whom.

'It will be observed that with the Pharisees forgiveness was an external thing; it was concerned not with the man himself but with his works – with these indeed as affecting him, but yet as existing independently without him. This was not the view taken by the best thought in the Old Testament. There forgiveness dealt first and chiefly with the direct relation between man's spirit and God; it was essentially a restoration of man to communion with God. When, therefore, Christianity had to deal with these problems, it could not accept the Pharisaic solutions, but had in some measure to return to the Old Testament to authenticate and develope the highest therein taught, and in the person and life of Christ to give it a world-wide power and comprehensiveness.'

The doctrine called Talmudic in the above extract receives remarkable illustration in a Jewish work, The Apocalypse of Baruch, which dates from the same period as the writings of the New Testament (A.D. 50-100; or if the work be regarded as composite, we should say that its component elements are of that date), and represents to us in a very vivid and touching form the hopes and beliefs of a pious orthodox Jew. Thus —

1. The doctrine of the merit of good works, ii. 2 [words spoken to Jeremiah by God], 'Your works are to this city as a firm pillar.' xiv. 5: 'What have they profited who confessed before Thee, and have not walked in vanity as the rest of the nations … but always feared Thee, and have not left Thy ways? And, lo, they have been carried off, nor on their account hast Thou had mercy on Zion. And if others did evil, it was due to Zion that on account of the works of those who wrought good works she should be forgiven, and should not be overwhelmed on account of the works of those who wrought unrighteousness.' lxiii. 3: 'Hezekiah trusted in his works, and had hope in his righteousness, and spake with the Mighty One … and the Mighty One heard him.' lxxxv. 1: 'In the generations of old those our fathers had helpers, righteous men and holy prophets … and they helped us when we sinned, and they prayed for us to Him who made us, because they trusted in their works, and the Mighty One heard their prayer and was gracious unto us.' li. 7: 'But those who have been saved by their works, and to whom the law has been now a hope, and understanding an expectation, and wisdom a confidence, to them wonders will appear in their time.'

It is very noticeable in the above quotations that it is the works of the righteous rather than their persons (as in Genesis xviii. 23-33) that are put forward as the grounds of confidence with God. The claim of righteousness in the second quotation (xiv. 5) may be paralleled in the somewhat earlier work called The Assumption of Moses[227]: 'Observe and know that neither did our fathers nor their forefathers tempt God so as to transgress His commandments.'

2. The doctrine of the treasury of merits. The good works of the righteous are laid up as in a treasury to avail for themselves and for others. Thus (xiv. 12): 'The righteous justly hope for the end, and without fear depart from this habitation, because they have with Thee a store of works preserved in treasuries.' xxiv. 1: 'Behold the days come when the books will be opened in which are written the sins of all those that have sinned, and again also the treasuries in which the righteousness of all those who have been righteous in creation is gathered.'

The connexion of the mediaeval doctrine of the treasury of merits with the similar Jewish doctrine needs to be traced out.

3. Righteousness identified with the keeping of the law. For the Pharisaic Jew righteousness meant simply the keeping of the law. Thus xv. 5: 'Man would not have rightly understood My judgement if he had not accepted the law.' Again, lxvii. 6: 'So far as Zion is delivered up and Jerusalem laid waste … the vapour of the smoke of the incense of righteousness which is by the law is extinguished in Zion.' Thus the merits of Abraham are attributed to his having kept the law before it was written. lvii. 2: 'At that time the unwritten law was named among them, and the works of the commandments were then fulfilled.'