полная версия

полная версияTrilbyana: The Rise and Progress of a Popular Novel

Philadelphia. John Patterson.

* * *To the Editors of The Critic: —

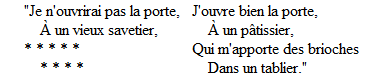

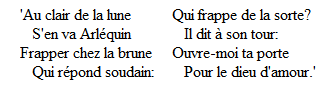

Du Maurier says that there is but one verse of the little French song, which Trilby sings with so much effect – "Au clair de la lune." He mistakes; there is another, running thus: —

The two missing lines have escaped the memory of the writer.

Auburn, N. Y. S. M. Cox.

—Your correspondent, S. M. Cox, offers some more verses of "Mon Ami Pierrot." They do not quite agree with those taught me, shortly after the Revolution of 1848, by an old French gentleman. You will notice that the French of the last verse is quite "eighteenth-century" in style and diction.

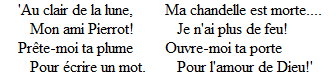

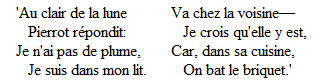

Mr. du Maurier was correct in saying that there is only one verse of "Au Clair de la Lune"; yet there are possibly, and probably, a thousand made in imitation of it, which go to the same air. We quote from the San Francisco Argonaut: —

"It is to be observed that these amateurs de Trilby do not go the length of singing 'Au Clair de la Lune,' even repeating the first stanza twice, as Trilby did. But perhaps they are as ignorant concerning the song as is Mr. du Maurier, who declares there is but one verse. There are four. The first is given in 'Trilby' thus: —

The second runs: —

The third stanza contains the point of the song: —

The fourth stanza continues in the same strain, and it goes farther."

—"Malbrouck s'en va't en Guerre"Malbrouck s'en va-t'en guerre —

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine!

Malbrouck s'en va-t'en guerre…

Ne sais quand reviendra!

Ne sais quand reviendra!

Ne sais quand reviendra!

Il reviendra-z-à Pâques —

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine!

Il reviendra-z-à Pâques…

Ou … à la Trinit!

La Trinité se passe —

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine!

La Trinité se passe…

Malbrouck ne revient pas!

Madame à sa tour monte —

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine!

Madame à sa tour monte,

Si haut qu'elle peut monter!

Elle voit de loin son page —

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine!

Elle voit de loin son page,

Tout de noire habillé!

"Mon page – mon beau page! —

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine!

Mon page – mon beau page!

Quelles nouvelles apportez?"

"Aux nouvelles que j'apporte —

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine!

Aux nouvelles que j'apporte,

Vos beaux yeux vont pleurer!"

"Quittez vos habits roses —

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine!

Quittez vos habits roses,

Et vos satins brochés!"

"Le Sieur Malbrouck est mort —

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine!

Le Sieur – Malbrouck – est – mort!

Est mort – et enterré!"

—There is no more eloquent description of the effect of music on an impressionable nature than du Maurier gives of the impression made upon Little Billee by the singing of Adam's "Cantique de Noël" at the Madeleine on Christmas Eve.

Cantique de NoëlMinuit, Chrétiens, c'est l'heure solennelle,Où l'homme Dieu descendit jusqu'à nous,Pour effacer la tache originelleEt de son Père arrêter le courroux.Le monde entier tressaille d'espéranceA cette nuit qui lui donne un sauveur.Peuple à genoux! attends la délivrance!Noël, Noël, voici le Rédempteur!A Search for Sources

To the Editors of The Critic: —

The liquid name, "Trilby," of du Maurier's heroine having been duly run down to its source, will a slight excursus be amiss as to the origin of the affectionate title applied by the novelist on his charming little hero – "Little Billee"? Evidently the name, together with certain descriptive touches, has been taken from Thackeray's ballad, "Little Billee." This racy skit, as many doubtless know, is in the best vein of the great humorist's inimitable burlesque. It narrates the tragic cruise of

"Three sailors of Bristol cityWho took a boat and went to sea,"the second stanza running thus: —

"There was gorging Jack, and guzzling JimmyAnd the youngest, he was Little Billee.Now when they got as far as the EquatorThey'd nothing left, but one split pea."And the unpleasant ultimatum being arrived at, that "We've nothing left, us must eat we," the poem continues: —

"Says gorging Jack to guzzling Jimmy,With one another we shouldn't agree,There's little Bill, he's young and tender,We're old and tough, so let's eat he."Here, I say, we have the origin of the novelist's "Little Billee," while, in the italicized phrases, we have also du Maurier's, "the third, he was little Billee" (page 6), and "he was young and tender, was little Billee."

It would be sheer nonsense, of course, to urge against the famous novelist any charge of unacknowledged borrowing in matters so entirely trivial. The point is merely a curious one of origins; a little siccatine botanizing, so to speak, on the folia disjecta that have been wonderfully spun by du Maurier's genius into a fabric of grace and beauty so rare as is this "Trilby." Nor, indeed, should the further fact be a detraction from the gifted author of "Trilby," that his indebtedness to Thackeray is obviously greater than in the minutiæ under consideration – that, in fact, he has caught from the great immortal the note of much that is best in his book. In his limpid, graceful simplicity of words, and their easy, natural flow – in his delicate, playful humor, and tender but not overwrought pathos, we discover a careful study of found only a few general remarks about fairies, their habits and habitations, nothing in the least resembling the story of Jeannie's lover. Perhaps Nodier was mistaken about his source. As he travelled in the Highlands, he may possibly have "collected" the tale at first hand, and, there being no folk-lore societies in those early days of romanticism, he was not aware of the honor that thus accrued to him. It cannot have evolved itself from a mere hint. We appeal to Mr. Lang to take up and follow the chase farther. He might be worse occupied than in tracing out the original John Trilby MacFarlane, and whence he got his English-sounding name, his fairy powers and his connection with Saint Columba – the last probably from Nodier himself, who may have been reading Montalembert's "Monks of the West" before setting out upon his pilgrimage. Mr. Dole, by the way, irreverently converts the Dove of the Churches into a "Saint Columbine," unknown to any respectable hagiographer. Think, Mr. Lang, what a delightful coil this romancing Frenchman, let loose among your Hielan' men, fairies, monks and Scotch novels, has made for you to straighten out, and how many strange discoveries may be made while you are about the job!

Miss Smith (2) has prepared another translation of Nodier's story, and, though there is little choice between her version and Mr. Dole's, we prefer it. It seems a trifle less exact, but it is more idiomatic; and, if anything, she perhaps intensifies the local color a little, which does not do the tale any harm. Her book is got up in tartan cover; Mr. Dole's has a design adapted from Paul Konewka.

* * *Mr. Richard Mansfield has secured from Estes & Lauriat the right to dramatize and produce Mr. Dole's translation of Nodier's "Trilby, le Lutin d'Argail."

Nodier's "Trilby, le Lutin d'Argail"

It was not long after the appearance of "Trilby" that our readers detected the French origin of the name of Mr. du Maurier's heroine. The story of the unearthing of this delightful French fairy-tale may be followed in this series of communications to The Critic:

—On looking over Roche's "Prosateurs Français," I find that one of the "plus jolis" contes of Charles Nodier (1788-1844) is entitled "Trilby"; therefore the title of du Maurier's much-bought novel is not original with him. I should be pleased if any reader of The Critic would inform me as to the plot of Nodier's story.

St. Francis of Assisi Rectory, Wm. J. McClure,

Mt. Kisco, N. Y., 29th Oct., 1894* * *The following lines occur in the "Réponse à M. Charles Nodier" of Alfred de Musset: —

"Non pas cette belle insomnieDu génieOù Trilby vient, prêt à chanter,T'écouter."This would seem to offer some clue to the origin of the name chosen by Mr. du Maurier for his heroine. Can you enlighten me as to the identity of the "Trilby" referred to by Musset?

Ridgefield, Conn., 19 Nov., 1894. Roswell Bacon.

* * *In answer to the request of your correspondent in The Critic of Nov. 17, I find the tale of "Trilby" in my copy of the "Contes de Charles Nodier, illustrés par Tony Johannot." "Trilby" is the story of a household fairy of Scotland (a "Lutin familier de la Chaumière"). It is fantastic and touching, but it has nothing in common with du Maurier's "Trilby."

Leesburgh, Virginia, 20 Nov., 1894. I. L. P.

* * *From the recent contributions to "Trilbyana" in your columns, it would appear as if the name of Trilby (originally Scotch or Irish?) were not uncommon in the writings of French authors. Charles Nodier, in his conte, says that M. de Latouche – a contemporary – wrote on the same subject, "où cette charmante tradition était racontée en vers enchanteurs" – which gives one to suppose that "Trilby" was the name of his enchantress; though, perhaps, he refers to the old story of "Le Diable Amoureux." I find, moreover, that Balzac takes the name for a type in his "Histoire des Treize: Ferragus: Vol. I. Scènes de la Vie Parisienne" (page 48 of edition of 1843): – "Pour développer cette histoire dans toute la vérité de ses détails, pour en suivre le cours dans toutes ses sinuosités, il faut ici divulguer quelques secrets de l'amour, se glisser sous les lambris d'une chambre à coucher, non pas effrontément, mais à la manière de Trilby [the opposite to du Maurier's Trilby], n'effaroucher ni Dougal, ni Jeannie, n'effaroucher personne," etc.

Tuxedo Park, 26 Nov., 1894. E. L. B.

* * *(Boston Evening Transcript, 1 Dec. 1894.)"The Listener was asked the other day where du Maurier got the name of Trilby – a sweet and pleasant word, neither English nor French, which seemed to suit so perfectly the adorable young person of his creation. He was able to answer, more by accident certainly than as the result of erudition, that the name was not invented by du Maurier but belongs to the French classics – possibly to Scottish folk-lore. In the year 1822 there was first published in Paris a nouvelle, by Charles Nodier, afterward a member of the French Academy, entitled, "Trilby, or the Fay of Argyle"; it was a sort of fairy-story, in which a fay is in love with a mortal woman, and the woman is very far from being indifferent to his sentiment. This 'Trilby' attained a considerable degree of popularity; it became, indeed, a French classic; Sainte-Beuve has particularly praised the charm of its style. * * * In his preface to the story, Nodier says: 'The subject of this story is derived from a preface or a note to one of the romances of Sir Walter Scott, I do not know which one.' This is a very indefinite acknowledgment While Nodier may have got his subject from Scott, the Listener doubts if he got the name 'Trilby' from him. It is just the sort of name that a French writer would give to a Scotch fay. Nevertheless, Trilby may be a real Scotch elfin. The Listener would hardly claim personal acquaintance with them all.

"Du Maurier's 'Trilby' is curiously prefigured, in part at least, in Nodier's; and yet there is not the smallest thing that the most jealous critic could call a plagiarism; it is a legitimate parentage. As you go on with Nodier's story, you love his Trilby more and more, as you do du Maurier's, until you think that there was never so bewitching a fairy; and your love for Trilby is interwoven with your love for Jeannie, his mortal sweetheart, just as your love for du Manner's Trilby is forever mixed up with your tender sentiment for Little Billee. You feel a sort of enchantment over you like the hypnotism that you are under in du Maurier's strange book. And both stories, while abounding in wit and pretty things, are deeply tragical. It has been said of Nodier's 'Trilby' that it belongs to the realm of the supra-sensible, and so, in large measure, certainly does du Maurier's. Du Maurier has confessed his obligation flatly in giving his story the very name that Nodier's bore. It is conceivable that the image of the Frenchman's haunting fairy dwelt with him until he resolved to reincarnate the adorable elf in the body of a girl as adorable. He gave his Trilby a Scotch ancestry to connect her the more naturally with the lutin d'Argail; and her fairy ancestry will easily account not only for her early prankishness, but for her later unreality. But it is a prefiguring merely, and not a direct suggestion. Whatever du Maurier's 'Trilby' lacks, it isn't originality!"

* * *(From Mr. C. E. L. Wingate's Boston Letter in The Critic of 20 April, 1893.)It appears that the first mention of the French book appeared in The Critic, last November. It was in the same month that Mr. Bradford Torrey * * * happened to find a copy of Nodier's "Trilby" in the Boston Athenæum. He took the book to his friend, Mr. J. E. Chamberlin of The Youth's Companion, who began its translation at once. A few days later appeared a note in The Critic from a correspondent in Virginia. Thinking that secrecy was no longer worth while, Mr. Chamberlin wrote his paragraphs for the Transcript "Listener" column, incorporating a bit of translation. This was printed on Dec. 1. Miss Minna C. Smith went to Roberts Bros. at once, to ask them if they would consider the publication of a translation of the romance by her Transcript confrère, and Mr. F. Alcott Pratt replied that they would like very much to see that gentleman's work. Circumstances made Mr. Chamberlin decide not to finish the translation, and he gave Miss Smith his idea and a few pages of the manuscript for a Christmas present. During several weeks following she was engaged upon her careful translation. The Scotch words and names of localities in her manuscript were corrected by Mr. J. Murray Kay of Houghton, Mifflin & Co., an accomplished Scot, who walked through Argyle with his daughters last summer. On March 19, an article on Charles Nodier's story, foreshadowing Miss Smith's translation, appeared in the Transcript. On the morning of March 20, Mr. Dana Estes sent for Mr. Nathan Haskell Dole and asked him to make a translation, which was done with remarkable rapidity, and put out on March 29. Learning of this, Lamson, Wolffe & Co. hurried on Miss Smith's book, which had been in the hands of their printer at the Collins press for days, advertised it on Thursday and brought it out on Saturday, in Scotch plaid covers.

This firm of Lamson, Wolffe & Co., by the way, has just been dissolved for a novel reason. Mr. Wolffe is a member of the class of '95 at Harvard. The publication of "Trilby, the Fairy of Argyle" called the attention of the faculty to his publishing business, and he was asked to give it up, or else forfeit his degree. He chose the former alternative, and although the firm name will remain Lamson, Wolffe & Co., a new and, for the present, silent member of the firm has added capital and scholarship to the house.

* * *"Trilby, the Fairy of Argyle"By Charles Noder. 1. Translated from the French, with introduction, by Nathan Haskell Dole. Estes & Lauriat. 2. From the French by Minna Caroline Smith. Boston: Lamson, Wolffe & Co.

Nodier's "Trilby," who now revisits the book-stores owing to Mr. du Maurier's having taken his name for his heroine's, is one of the few latter-day fairies that have fairy blood (or ichor) in their veins. He belongs on the same shelf with Fouqué's "Undine," but, though he was only joking when he personated a father who "had not seen him since the days of King Fergus," he is certainly of the breed of Una and Maer, Caoilte and Mananan. That he made a sensation on his first appearance in the world of letters is shown by Victor Hugo's ode, warning the Fairy of Argyle to beware of ink-slinging penny-a-liners: —

"Car on en veut aux Trilbys* * * * * * * *Ils souilleraient d'encre noire,Hélas! ton manteau de moire,Ton aigrette de rubis" —advice which might be repeated apropos of Mr. du Maurier's creation.

Mr. Dole, who has made a translation (1) of Nodier's "Trilby," has looked through all of Scott's novels, he says, to discover, if possible, the "preface or note" from which the French author claimed to have drawn his story, and has the deft art of "Pendennis" and "The Newcomes." And the "Cave of Harmony," with its songs and its bumpers and long whiffs, the gay nights and rollicking days of F. B. and Clive and Pendennis – the glamor of all which has enticed full many a youngster towards the easy descent, or the shining slopes (as the case may be) of art and letters – all these scenes have doubtless served as the studies of the pictures, almost as delightful and masterly as their prototypes, that du Maurier gives us of the joyous Bohemian life of the three jolly Musketeers of the Brush in the Quartier Latin in "Trilby."

Auburn, Ala., 26 Dec., 1894. Charles C. Thach.

* * *As a small contribution to "Trilbyana," I would call attention to the fact, unnoted so far, that Trilby was the name of Eugénie de Guérin's pet dog, mentioned several times in the journal she kept for her brother Maurice. Was the dog, perhaps, named for the fairy?

Louisville, Ky. A. C. B.

* * *As there seems to be a mania for hunting up the sources of the inspiration of certain authors, I will engage in the game also. In Saintine's "Picciola," Book I., Chap XII., after the first paragraph, you will find the germ of "Peter Ibbetson."

Grand Rapids, Mich. C. C.

1

See frontispiece.

2

Unless in amended form.