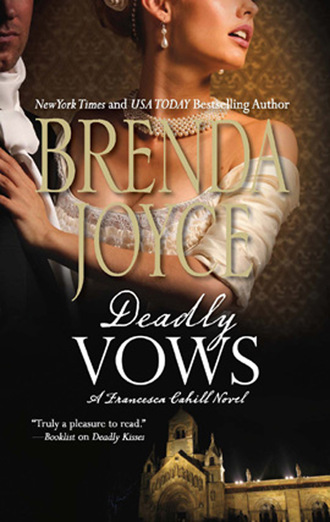

Полная версия

Deadly Vows

Francesca laughed, her worries vanishing. All she could think of was Hart watching her with that dark, intense gaze he had as she walked down the aisle. “God only knows how you convinced Father to agree to a wedding in two weeks.”

“I think Hart did that,” Connie said. “Neil saw them at Delmonico’s, having lunch. By the way, he said Father looked apoplectic.”

Francesca bit her lip. Hart hadn’t said a word about meeting with her father before he’d left town, but clearly he had done just that. She happened to know how adept Hart was at negotiation. Obviously Andrew Cahill, no slouch when it came to business affairs—he had begun his career as a butcher and now ran a meatpacking empire—had been vastly outmaneuvered.

“Have you seen your fiancé since he returned from Chicago?”

“We had a wonderful supper the night before last.” She blushed, thinking about it.

“I wish we had been able to organize an affair for last night, but it was difficult enough to prepare the wedding,” Connie said. A knock sounded on the closed salon doors and she turned to answer it.

Francesca murmured, “Hart was given a small bachelor’s party last night.”

Connie blushed and said, “I do not want to know.”

“Neither do I,” Francesca lied. She couldn’t wait to find out where he had been taken and what kind of entertainment he’d been given.

The doorman, Jonathon, was holding an envelope in his hand. “Miss Cahill? This just came. I was told to deliver it directly to you and no one else.”

Flowers wouldn’t have surprised her, but such a delivery did. Francesca couldn’t imagine what the envelope would contain, or why it had been hand delivered. As Jonathon walked past her, Connie glanced at the envelope. She lost some of her coloring.

Francesca saw her reaction and was bemused. She reached for the envelope and froze. It wasn’t addressed to her. Instead, a single word in heavy block letters was hand-written upon it: URGENT.

Francesca was assailed with unease. Connie cried sharply, “Fran, do not open it!”

Francesca took the envelope, thanking Jonathon. “That is all,” she said. She waited for him to leave and turned it over. The back was blank.

Connie came over to her. “I know you. That must be the beginning of an investigation. It is your wedding day, Fran. Do not open it!”

“I am not going to start an investigation today, Con,” Francesca said calmly. She walked away from her sister, ostensibly to stand in the light coming through a window. In fact, she did not want her sister to see the contents of the envelope until she had done so first.

A printed invitation was inside. It read:

A private preview of the works of Sarah Channing

On Saturday, June 28, 1902

Between the hours of 1:00-4:00 p.m.

At No. 69 Waverly Place

Francesca felt her heart drop as if to the floor. Her knees buckled. She could only stare at the invitation in horror.

“What is it?” Connie cried, rushing forward. “Has someone died?”

Francesca quickly held the card to her bosom so her sister could not see. She looked at Connie, but her mind spun and she did not see her sister at all. Instead, she saw the portrait Sarah had painted of her last April, at Hart’s request. In it, she was stark naked, seated on a settee.

Her stolen portrait had surfaced.

Someone had just invited her to view it.

She inhaled. Francesca had no doubt what this terrible in vitation was about.

“Fran? Let me get you a glass of water.”

Francesca sat down, hard, in the closest chair. Her sister knew that Hart had commissioned her portrait and that it had been stolen, but she did not know that it was a nude. Only a handful of people knew.

Her heart thundered. If that portrait were ever displayed in public, she was ruined. Her family would be more than horrified and shamed—they would be ruined by association with her.

Of all days for the thief to come forward. What did he or she want?

“Con, no, I am fine!” Francesca leaped to her feet. It was only half past eleven. She could be at 69 Waverly Place in an hour—maybe less, considering a great deal of the city was already gone for the summer. Surely she could be at the church by three, with plenty of time to dress for her wedding.

No one must ever see that portrait!

Connie faced her, her eyes wide. “What is it?”

Francesca managed a smile. “I need a favor, Con, a huge favor—”

“No. Whatever is in that note, it can wait.” Connie was frowning. Her mild-mannered sister was becoming angry.

She kept smiling. “I need you to bring my dress, my shoes and my jewelry to the church. I will meet you there at three.”

“Absolutely not,” Connie cried, horrified.

“Connie, if I do not take care of this—this matter now, I will be in terrible trouble!”

“Take care of this matter after you are married.”

“Connie, I am going downtown. I will be at the church by three, I swear. Nothing can keep me away!”

CHAPTER TWO

Saturday, June 28, 1902

12:00 p.m.

RICK BRAGG STARED at his Victorian home, the engine of the Daimler idling, but he did not really see the quaint brick house. Instead, the interview he’d just had with Francesca kept replaying in his mind. He was very afraid for her.

He knew Hart would eventually destroy her. His brother had a black, selfish soul. He was cruel and self-involved. From time to time he could rise to the occasion, briefly showing the honorable side of his nature, but in the end, he always reverted to serving only his own interests and ambitions. Francesca was selfless. Hart was selfish. No match could be worse.

But he was hardly an impartial observer. Bragg was afraid to recall the past he had shared with Francesca. He feared that too many old feelings would return. He knew he must not think of the time they had first met, when he had been smitten with her—and she had returned his passionate interest. He must not think about their debates, their discussions, their investigations—or the kisses and caresses they had shared. That was wrong. His wife had returned after leaving him four years ago, and as uneasy as it was, as angry as he had been, they had reconciled. Besides, before Francesca had become charmed by his brother, she had utterly rejected the notion of his ever divorcing. Although he never spoke openly about it, in the most elite political circles it was assumed that one day he would run for office, possibly even for the United States Senate. A divorce would ruin his political prospects.

He had made his own bed, which he now slept in. Leigh Anne had insisted on moving back in with him—and when she had, he had insisted on his marital rights. He had been furious with her for both leaving him and then returning to him. What had begun as an unfriendly reconciliation had turned into a passionate one, but his lust had been fed by his anger.

He had spent half of last night working, the other half thinking about the fact that Francesca was actually going to marry his heartless half brother on the morrow. He did not know where the past few weeks had gone. He had been overwhelmed at headquarters. There had been a series of civilian arrests in the Tenderloin—organized, of course, by the radical reformer Reverend Parkhurst, whose motives were political. Parkhurst vociferously claimed it was his duty as an American citizen to do what the police would not, which was to close the saloons on Sundays, while the press sensationalized every detail of every civilian raid, putting Bragg in the midst of the dispute. The mayor was furious with Parkhurst, but he was also displeased with Bragg. And Leigh Anne had begun to complain of pains in her leg.…

And then he had received the damn wedding invitation, only a week ago!

He was certain he could support Francesca’s marriage to someone else—someone worthy of her. Hart was not that man. But what could he do? He had tried to persuade her to delay, and she had refused. Now, he would have to stand aside and be ready to pick her up when Hart shattered her into tiny pieces. Bragg had not a doubt that was what his half brother would do.

He realized that the automobile was still running and he turned off the ignition. Reluctantly, he got out of the roadster, placing his goggles on the driver’s seat. The holiday weekend loomed. He would take his wife and the two girls fostering with them to the tiny village hamlet of Sag Harbor, on Long Island’s north shore. He had spent all of the prior night at his office at police headquarters, taking care of paperwork that only he could manage—the perfect excuse to stay overnight at the office. It wasn’t the first time; he had begun keeping a change of clothing there. He was astute enough to realize that he dreaded returning home. He wasn’t sure when he had begun to avoid his marriage.

The anger was long gone. It had been replaced by guilt. He had treated Leigh Anne terribly before she was injured. While she did not blame him for the accident, he blamed himself. His cruelty had put her in such a state of distraction that she had been run down.

As for the lust, every time he thought about reaching for her, she would turn away, or feign sleep, or make some excuse that one of the girls was awake, needing her.

He was hardly a fool. Leigh Anne was a passionate woman, but she was also vain and she couldn’t stand the changes the accident had wrought in her body.

She had even told him to take a mistress; she had even asked for a divorce. How ironic it was. He had been the one who had wanted a divorce when she suddenly reappeared in his life in February, while she had insisted on reconciliation! He wondered what was left for them, if they didn’t have conversation, understanding, affection or sex. He would never turn his back on her now. Even if he knew rationally that the accident wasn’t really his fault, she was his wife. If he didn’t take care of her, who would?

He walked grimly past a small black gig and gray horse parked in the driveway. He instantly recognized the vehicle, and his tension increased. Leigh Anne must have summoned Dr. Finney.

He focused on the fact that she must be in more pain—it was preferable to thinking about their volatile and unhappy relationship. He started up the brick path to the small house he had leased, hoping the girls were in the park with their nanny so they would not witness Leigh Anne’s distress. He stepped into the house, plastering a smile on his face. Instantly he heard a noise on the stairs. Katie came barreling down the staircase so swiftly he reached for her, afraid she would trip and fall. Her small face was taut with worry. His heart lurched with dismay.

He knelt. “What’s wrong?”

“Mrs. Bragg hurts so much,” she cried, looking at him as if he might be able to somehow save the day. She was dark haired and seven years old.

Katie was always anxious. When she came to them after her mother’s murder, she had refused to speak or eat. Now she spoke, although not frequently, and ate like a little horse. She even smiled from time to time, especially when Leigh Anne was at her best and mothering her. But she worried about her foster mother all the time and he knew it was not healthy for her. He clasped her thin shoulders. “Katie, Mrs. Bragg was badly hurt in that carriage accident. Now and then, she will have some old pain, left over from her injuries.”

“Why won’t it stop?” she whispered, her dark eyes huge and despairing.

“She has her good days, too. I am going to go upstairs to see what Dr. Finney has to say. Where is Dot?”

“She is having lunch.”

“Why don’t you join her. Aren’t you hungry? Mrs. Flowers is a wonderful cook.” He managed a smile.

Katie did not smile back, but she reluctantly turned. He hurried upstairs, his heart racing. Amazingly, he was anxious. He paused on the threshold of their bedroom, wondering how a man could live this way—in dread of going home, to a place without laughter and affection, without sex; in a state of constant apprehension. And then there was the guilt.

Leigh Anne wasn’t dressed yet. She wore a modest blue silk wrapper, her jet-black hair piled indifferently atop her head. She had the covers up and a wool throw over her lap, as if she was cold. Finney sat by the bed, speaking with her, patting her hand. His wife remained terribly beautiful, but she appeared as fragile as china.

Leigh Anne saw him and sat up straighter, as if stiffening her spine and squaring her shoulders. He slowly entered the room. “How are you?”

She said, “The pain is worse.”

Dr. Finney walked over. The two men shook hands. The doctor spoke softly. “I have given her some laudanum, to dose herself at night. She says she cannot sleep.”

“There is nothing wrong with her leg,” Bragg said tersely. “Those broken bones have healed.”

“Considering there was so much damage, I suspect she will always have some discomfort with her right leg. Try to make sure she does not rely on the laudanum to sleep. She should only dose herself if absolutely necessary.”

“I’ll see to it,” Bragg said. “Let me walk you out.”

“I can manage.” Finney gripped his shoulder. “See you later, eh? At Hart’s wedding?” He shook his head, as if in disbelief, and walked out.

Slowly, Bragg turned.

“I heard every word,” Leigh Anne said, her cheeks flushed.

“I am sorry you are in pain,” he returned.

“Where are the girls?”

He was aware of how much she had come to love Katie and Dot. He wondered if she was desperately clinging to them. “They are having lunch.” He approached, and her eyes widened. As he sat down on the bed by her hip, she tensed visibly, and he wondered if she thought he meant to try to make love to her. In that moment, there was no desire, just a fatigue that felt ancient.

But he knew himself. If she were to reach for him, he would lose himself in lust. He said carefully, “It’s after one. Shouldn’t you be getting dressed?”

She hesitated. “I do not feel up to the wedding.”

He was shocked. Leigh Anne loved society affairs, and although it was late June, this event would be in every single social column from Bar Harbor to Charleston. He thought about the fact that she hadn’t gone out in the past few days, not even to be pushed about the block or across the square in her wheelchair. When they had first met, she had been one of Boston’s reigning debutantes. Until recently, Leigh Anne had attended almost every luncheon to which she had been invited. She had been at his side at every supper party and charity she had deemed important to his career. He understood that she was melancholy, but it would only become worse if she did not get out.

She grimaced. “Of course I will come. And you’re right, I should begin getting dressed. Where is Nanette?”

He had had to hire a lady’s maid to help her bathe and dress. As his finances were precarious, he had let the male nurse go. “I will send her up,” he said as lightly as possible.

She forced a smile, avoiding his eyes. He went to the door. Then he halted. He hated seeing her so despondent. But how could he cheer her up? Maybe he should tell her that she did not have to go to the wedding if she truly did not feel well. Bragg turned.

Leigh Anne was pouring brandy from a pint-size bottle into her cup of tea.

FRANCESCA HAD BECOME very familiar with many of the unsavory, crime-ridden lower wards of Manhattan. Still, it was a large city, filled with slums and tenements, factories and saloons, with neighborhoods populated by Germans, Italians and Irish, not to mention Russians, Poles and Jews. In the course of her many adventures, she had even learned that there was a “Little Africa” on the Lower East Side. The various immigrant groups migrating to the city resided in distinct ethnic clusters.

She was proud that she knew the city well, but she did not know it like the back of her hand. In her very first investigation—into the abduction of a neighbor’s child—she had met a young, outspoken cutpurse, eleven-year-old Joel Kennedy. He had defended her from a thug, and she had taken him under her wing, not just because he knew so many tricks of the trade, but because she had a secret wish to help him improve his lot in life. When she did not have Joel with her—a rare circumstance indeed—she used a map to navigate Manhattan. Today, Joel was with his mother, Maggie, a wonderful seamstress who had become her friend—and possibly a romantic interest of her brother’s. She could imagine the chaos in the Kennedy home just then, as Maggie had been stunned to have been invited to her wedding. Undoubtedly Joel and his siblings were being groomed for the event.

But she did not need her maps. The cabbie she flagged down on the avenue instantly told her that No. 69 Waverly Place was on the north side of Washington Square.

Francesca was relieved. The previewing was but a few blocks from 300 Mulberry Street—which housed police headquarters.

She was on pins and needles. She had not a doubt in her mind that her portrait was at No. 69 Waverly Place. She had begun to wonder if someone wished to agitate her on her wedding day. If so, that someone had certainly succeeded!

Earlier, she had been relieved to find her father’s study empty; perhaps Andrew had been taking his weekend ambulatory in the park. She had made one quick telephone call before leaving the house, and it would have been quicker if the operator, Beatrice, hadn’t tried to converse with her about her wedding. But Hart hadn’t been home—she couldn’t imagine what he was doing on their wedding day—and she had spoken to his butler, Alfred. The butler had asked her if she wished to leave a message, but she had been too frenzied to get downtown to think of anything coherent to say. Before dashing out of the house, Connie had told her that she was a madwoman.

Francesca looked at the small pocket watch she had bought for herself recently; crime-solving was laborious, and she tended to run late. It was half past one. It had taken longer to get downtown than she had thought it would, but she had a good hour yet to explore.

They were on Fifth Avenue, traveling south. Ahead, she saw the green lawns and paved walkways of Washington Square. On both sides of Fifth Avenue she saw old brownstone buildings that were clearly residences, although she also saw a few ground-floor restaurants and taverns. Her hansom turned left onto Waverly Place, which faced the square. More dark brownstones lined the block, shaded by elm trees. Shops were on the lower floors.

She caught the bright sign hanging from one such establishment: Gallery Moore.

“Stop, driver, stop!” Her gaze sought the number above the sign. It was No. 69.

Frantically, Francesca dug into her purse.

“Do you want me to wait, miss?” the cabbie asked. He had a heavy Italian accent.

Francesca quickly looked around. Despite the holiday, the square was full. Women in pretty cotton dresses, some with parasols, were strolling with their children or their gentlemen escorts. Some of the men were in their shirtsleeves, while a few wore suit jackets and top hats. Two cyclists, one a woman in knickers, were on bicycles, weaving precariously along the paths. A few small dogs raced about, while a balloon drifted into the sky. It was a very pleasant, genteel scene.

She looked at the block facing her. Once, the buildings had been fashionable, single-family Georgian homes. There were daffodils growing about the elm trees on the sidewalks, and she saw more flowers in the window boxes. Washington Square was a tired and old neighborhood, but it remained middle-class. Another hansom was passing by and she decided it was safe to let the cabdriver go.

She was in such a rush that she stumbled from the cab. Slamming the door, she turned to face the gallery. Her heart thundered.

Everyone seemed to be in the square; the city block was deserted.

She paused to take her small pistol from her purse. It was loaded. Whoever had stolen her portrait, he or she was, at the least, a thief. And she would certainly not be surprised if that thief was also a blackmailer or an enemy, seeking revenge upon her. She would be a fool to deny her fear.

Her stolen portrait could be inside. She prayed that it was.

There were wide stone steps on her right, leading to the apartments above the gallery. The gallery itself was on the basement level, meaning she had to go down several steps to get to the front door. As she did, the first thing she saw was the white sign hanging on the door. Its bold black letters read Closed.

She paused, clutching the small gun. The door was glass, but set in iron and barred with it. She glanced at the windows on each side, which were similarly barred. Most galleries had large windows, to allow in natural light. She imagined that it was dark and gloomy inside this space.

A smaller sign was in the right-hand window. She went closer to read it.

Summer Hours: Monday-Friday, 12:00–5:00 p.m.

The gallery was closed to the public. Francesca felt her heart leap with relief, but that did not dim her anxiety. A small doorbell was beside the door, and there was a heavy iron knocker on it. Francesca reached for the doorknob.

It gave instantly as she turned it, and the front door swung open.

Clearly, someone was waiting for her.

In that moment, she wished that Hart had been at home, or that Bragg had still been present when she had gotten the invitation. She blinked, adjusting her eyes to the gloom inside. No lights were on, so the gallery was filled with shadow.

Francesca stepped in and closed the door behind her very, very quietly. To her satisfaction, she did not hear even the scrape of iron on the floor.

She could see well enough now and she turned, her skin beginning to prickle, certain she was not alone. She almost gasped.

Her portrait faced her.

She trembled. She had forgotten how stunning the painting was—and how provocative. In it, she wore nothing but a pearl choker. Her hair was up and perfectly coiffed. She sat with her back to the viewer, but she was partially turned. Not only were most of her buttocks visible, so was the entire profile of one of her breasts.

There was no mistaking her identity—and to make matters worse, she wore an expression of naked sensuality and raw hunger.

When she had posed for that painting, all she could think about was Hart.

Her instinct was to rush forward and yank the picture from the wall and destroy it. But there would be time for that later. She fought for composure. What did the thief want? Why surface now? Did he or she want money? Did he or she want to ruin her?

Was she being watched?

She felt as if eyes were upon her—and she did not like it, not one damn bit. She had her back to the door. She looked outside through the bars and glass, but the small concrete space beyond the front door was vacant.

Francesca started forward, gun in hand. If the thief was watching her, there was no point in remaining silent. Now she saw the other paintings on the walls. None were Sarah Channing’s work. Her style, somewhat classical yet impressionistic, too, was very distinct. “Where are you?” she called out loudly, turning the corner behind the center wall. The area there boasted nothing but blank gray walls. “Who are you? What do you want?”

Her words seemed to echo slightly in this smaller back chamber. She saw an open doorway, but hesitated. “Come out. I know you’re here.” She swallowed, straining to listen. All she could hear was her own thundering heartbeat and her rapid, shallow breathing.

She was afraid. Why wouldn’t she be? Someone had lured her to that gallery. She needed to take possession of that painting. “I will pay you handsomely for my portrait!” she cried.

There was no answer.

Standing in the back room, facing a dark, open doorway, she knew a moment of despair. What kind of game was this?

She hated releasing her gun, but she tucked it in the waistband of her skirt, only so she could remove matches and a candle from her purse. Months ago, she had learned to carry a large bag in order to keep the necessities of her trade with her. She lit the candle and realized the small doorway belonged to a single room, which consisted of a desk, a chair and file cabinets.