полная версия

полная версияMichael Faraday

It was soon inspected by Faraday inside and outside, by land and by sea. His notes terminate in this way: – "Went to the hills round, about a mile off, or perhaps more, so as to see both upper and lower light at once. The effect was very fine. The lower light does not come near the upper in its power, and, as to colour, looks red whilst the upper is white. The visible rays proceed from both horizontally, but those from the low light are not half so long as those from the electric light. The radiation from the upper light was beautifully horizontal, going out right and left with intenseness like a horizontal flood of light, with blackness above and blackness below, yet the sky was clear and the stars shining brightly. It seemed as if the lanthorn28 only were above the earth, so dark was the path immediately below the lanthorn, yet the whole tower was visible from the place. As to the shadows of the uprights, one could walk into one and across, and see the diminution of the light, and could easily see when the edge of the shadow was passed. They varied in width according to the distance from the lanthorn. With upright bars their effect is considerable at a distance, as seen last night; but inclining these bars would help in the distance, though not so much as with a light having considerable upright dimension, as is the case with an oil-lamp.

"The shadows on a white card are very clear on the edge – a watch very distinct and legible. On lowering the head near certain valleys, the feeble shadow of the distant grass and leaves was evident. The light was beautifully steady and bright, with no signs of variation – the appearance was such as to give confidence to the mind – no doubt about its continuance.

"As a light it is unexceptionable – as a magneto-electric light wonderful – and seems to have all the adjustments of quality and more than can be applied to a voltaic electric light or a Ruhmkorff coil."

The Royal Commissioners and others saw with gratification this beautiful light, and arrangements were made for getting systematic observations of it by the keepers of all the lighthouses within view, the masters of the light-vessels that guard the Goodwin Sands, and the crews of pilot cutters; after which Faraday wrote a very favourable report, saying, among other things: "I beg to state that in my opinion Professor Holmes has practically established the fitness and sufficiency of the magneto-electric light for lighthouse purposes, so far as its nature and management are concerned. The light produced is powerful beyond any other that I have yet seen so applied, and in principle may be accumulated to any degree; its regularity in the lanthorn is great, its management easy, and its care there may be confided to attentive keepers of the ordinary degree of intellect and knowledge."29

The Elder Brethren then wished a further trial of six months, during which time the light was to be entirely under their own control. It was therefore again kindled on August 22, and the experiment happened soon to be exposed to a severe test, as one of the light-keepers, who had been accustomed to the arrangement of the lamps in the lantern, was suddenly removed, and another took his place without any previous instruction. This man thought the light sufficiently strong if he allowed the carbon points to touch, as the lamp then required no attendance whatever, and he could leave it in that way for hours together. On being remonstrated with, he said, "It is quite good enough." Notwithstanding such difficulties as these, the experiment was considered satisfactory, but it was discontinued at the South Foreland, for the cliffs there are marked by a double light, and the electric spark was so much brighter than the oil flames in the other house, that there was no small danger of its being seen alone in thick weather, and thus fatally misleading some unfortunate vessel.

After this Faraday made further observations, estimates of the expense, and experiments on the divergence of the beam, while Mr. Holmes worked away at Northfleet perfecting his apparatus, and the authorities debated whether it was to be exhibited again at the Start, which is a revolving light, or at Dungeness, which is fixed. The scientific adviser was in favour of the Start, but after an interview with Mr. Milner Gibson, then President of the Board of Trade, Dungeness was determined on; a beautiful small combination of lenses and prisms was made expressly for it by Messrs. Chance, and at last, after two years' delay, the light again shone on our southern coast.

It may be well to describe the apparatus. There are 120 permanent magnets, weighing about 50 lbs. each, ranged on the periphery of two large wheels. A steam-engine of about three-horse power causes a series of 180 soft iron cores, surrounded by coils of wire, to rotate past the magnets. This calls the power into action, and the small streams of electricity are all collected together, and by what is called a "commutator" the alternative positive and negative currents are brought into one direction. The whole power is then conveyed by a thick wire from the engine-house to the lighthouse tower, and up into the centre of the glass apparatus. There it passes between two charcoal points, and produces an intensely brilliant continuous spark. At sunset the machine is started, making about 100 revolutions per minute; and the attendant has only to draw two bolts in the lamp, when the power thus spun in the engine-room bursts into light of full intensity. The "lamp" regulates itself, so as to keep the points always at a proper distance apart, and continues to burn, needing little or no attention for three hours and a half, when, the charcoals being consumed, the lamp must be changed, but this is done without extinguishing the light.

Again there were inspections, and reports from pilots and other observers, and Faraday propounded lists of questions to the engineer about bolts and screws and donkey-engines, while he estimated that at the Varne light-ship, about equidistant from Cape Grisnez and Dungeness, the maximum effect of the revolving French light was equalled by the constant gleam from the English tower. But delays again ensued till intelligent keepers could be found and properly instructed; but on the 6th June, 1862, Faraday's own light, the baby grown into a giant, shone permanently on the coast of Britain.

France, too, was alert. Berlioz's machine, which was displayed at the International Exhibition in London, and which was also examined by Faraday, was approved by the French Government, and was soon illuminating the double lighthouse near Havre. These magneto-electric lights on either side of the Channel have stood the test of years; and during the last two years there has shone another still more beautiful one at Souter Point, near Tynemouth; while the narrow strait between England and France is now guarded by these "sentinels of peaceful progress," for the revolving light at Grisnez has been lately illuminated on this principle, and on the 1st of January, 1872, the two lights of the South Foreland flashed forth with the electric flame.30

In describing thus the valuable applications of Faraday's discoveries of benzol, of specific inductive capacity, and of magneto-electricity, it is not intended to exalt these above other discoveries which as yet have paid no tribute to the material wants of man. The good fruit borne by other researches may not be sufficiently mature, but it doubtless contains the seeds of many useful inventions. Yet, after all, we must not measure the worth of Faraday's discoveries by any standard of practical utility in the present or in the future. His chief merit is that he enlarged so much the boundaries of our knowledge of the physical forces, opened up so many new realms of thought, and won so many heights which have become the starting-points for other explorers.

SUPPLEMENTARY PORTRAITS

It has been said that there is no photograph or painting of Faraday which is a satisfactory likeness; not because good portraits have never been published, but because they cannot give the varied and ever-shifting expression of his features. Similarly, I fear that the mental portraiture which I have attempted will fail to satisfy his intimate acquaintance. Yet, as one who never saw him in the flesh may gain a good idea of his personal appearance by comparing several pictures, so the reader may learn more of his intellectual and moral features by combining the several estimates which have been made by different minds. Earlier biographies have been already referred to, but my sketch may well be supplemented by an anonymous poem that appeared immediately after his death, and by the words of two of the most distinguished foreign philosophers – Messrs. De la Rive and Dumas.

"Statesmen and soldiers, authors, artists, – stillThe topmost leaves fall off our English oak:Some in green summer's prime, some in the chillOf autumn-tide, some by late winter's stroke."Another leaf has dropped on that sere heap —One that hung highest; earliest to inviteThe golden kiss of morn, and last to keepThe fire of eve – but still turned to the light."No soldier's, statesman's, poet's, painter's nameWas this, thro' which is drawn Death's last black line;But one of rarer, if not loftier fame —A priest of Truth, who lived within her shrine."A priest of Truth: his office to expoundEarth's mysteries to all who willed to hear —Who in the book of Science sought and found,With love, that knew all reverence, but no fear."A priest, who prayed as well as ministered:Who grasped the faith he preached; and held it fast:Knowing the light he followed never stirred,Howe'er might drive the clouds thro' which it past."And if Truth's priest, servant of Science too,Whose work was wrought for love and not for gain:Not one of those who serve but to ensueTheir private profit: lordship to attain"Over their lord, and bind him in green withes,For grinding at the mill 'neath rod and cord;Of the large grist that they may take their tithes —So some serve Science that call Science lord."One rule his life was fashioned to fulfil:That he who tends Truth's shrine, and does the hestOf Science, with a humble, faithful will,The God of Truth and Knowledge serveth best."And from his humbleness what heights he won!By slow march of induction, pace on pace,Scaling the peaks that seemed to strike the sun,Whence few can look, unblinded, in his face."Until he reached the stand which they that winA bird's-eye glance o'er Nature's realm may throw;Whence the mind's ken by larger sweeps takes inWhat seems confusion, looked at from below."Till out of seeming chaos order grows,In ever-widening orbs of Law restrained,And the Creation's mighty music flowsIn perfect harmony, serene, sustained;"And from varieties of force and power,A larger unity, and larger still,Broadens to view, till in some breathless hourAll force is known, grasped in a central Will,"Thunder and light revealed as one same strength —Modes of the force that works at Nature's heart —And through the Universe's veinèd lengthBids, wave on wave, mysterious pulses dart."That cosmic heart-beat it was his to list,To trace those pulses in their ebb and flowTowards the fountain-head, where they subsistIn form as yet not given e'en him to know."Yet, living face to face with these great laws,Great truths, great myst'ries, all who saw him nearKnew him for child-like, simple, free from flawsOf temper, full of love that casts out fear:"Untired in charity, of cheer serene;Not caring world's wealth or good word to earn;Childhood's or manhood's ear content to win;And still as glad to teach as meek to learn."Such lives are precious: not so much for allOf wider insight won where they have striven,As for the still small voice with which they callAlong the beamy way from earth to heaven." Punch, September 7, 1867.The estimate of M. A. de la Rive is from a letter he addressed to Faraday himself: —

"I am grieved to hear that your brain is weary; this has sometimes happened on former occasions, in consequence of your numerous and persevering labours, and you will bear in mind that a little rest is necessary to restore you. You possess that which best contributes to peace of mind and serenity of spirit – a full and perfect faith, a pure and tranquil conscience, filling your heart with the glorious hopes which the Gospel imparts. You have also the advantage of having always led a smooth and well-regulated life, free from ambition, and therefore exempt from all the anxieties and drawbacks which are inseparable from it. Honour has sought you in spite of yourself; you have known, without despising it, how to value it at its true worth. You have known how to gain the high esteem, and at the same time the affection, of all those acquainted with you.

"Moreover, thanks to the goodness of God, you have not suffered any of those family misfortunes which crush one's life. You should, therefore, watch the approach of old age without fear and without bitterness, having the comforting feeling that the wonders which you have been able to decipher in the book of nature must contribute to the greater reverence and adoration of their Supreme Author.

"Such, my dear friend, is the impression that your beautiful life always leaves upon me; and when I compare it with our troubled and ill-fulfilled life-course, with all that accumulation of drawbacks and griefs by which mine in particular has been attended, I put you down as very happy, especially as you are worthy of your good fortune. This leads me to reflect on the miserable state of those who are without that religious faith which you possess in so great a degree."

In M. Dumas' Eloge at the Académie des Sciences, occur the following sentences: —

"I do not know whether there is a savant who would not feel happy in leaving behind him such works as those with which Faraday has gladdened his contemporaries, and which he has left as a legacy to posterity: but I am certain that all those who have known him would wish to approach that moral perfection which he attained to without effort. In him it appeared to be a natural grace, which made him a professor full of ardour for the diffusion of truth, an indefatigable worker, full of enthusiasm and sprightliness in his laboratory, the best and most amiable of men in the bosom of his family, and the most enlightened preacher amongst the humble flock whose faith he followed.

"The simplicity of his heart, his candour, his ardent love of the truth, his fellow-interest in all the successes, and ingenuous admiration of all the discoveries of others, his natural modesty in regard to what he himself discovered, his noble soul – independent and bold, – all these combined gave an incomparable charm to the features of the illustrious physicist.

"I have never known a man more worthy of being loved, of being admired, of being mourned.

"Fidelity to his religious faith, and the constant observance of the moral law, constitute the ruling characteristics of his life. Doubtless his firm belief in that justice on high which weighs all our merits, in that sovereign goodness which weighs all our sufferings, did not inspire Faraday with his great discoveries, but it gave him the straightforwardness, the self-respect, the self-control, and the spirit of justice, which enabled him to combat evil fortune with boldness, and to accept prosperity without being puffed up…

"There was nothing dramatic in the life of Faraday. It should be presented under that simplicity of aspect which is the grandeur of it. There is, however, more than one useful lesson to be learnt from the proper study of this illustrious man, whose youth endured poverty with dignity, whose mature age bore honours with moderation, and whose last years have just passed gently away surrounded by marks of respect and tender affection."

APPENDIX

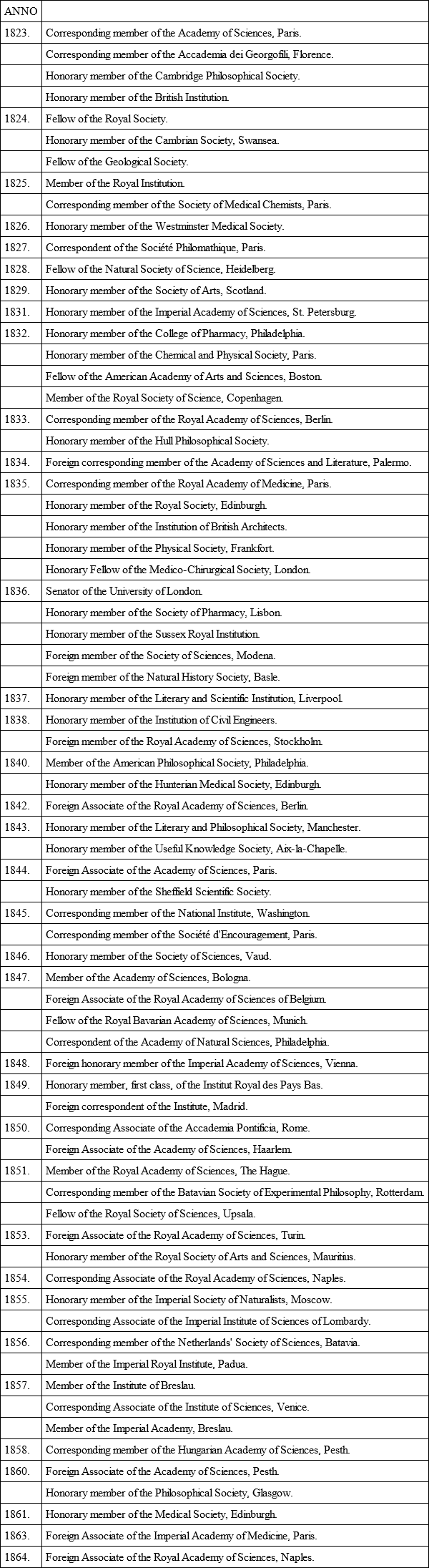

LIST OF LEARNED SOCIETIES TO WHICH MICHAEL FARADAY BELONGED

1

These books, with others bound by Faraday, are preserved in a special cabinet at the Royal Institution, together with more valuable documents, – the laboratory notes of Davy and those of Faraday, his notes of Tatum's and Davy's lectures, copies of his published papers with annotations and indices, notes for lectures and Friday evening discourses, account books, and various memoranda, together with letters from Wollaston, Young, Herschel, Whewell, Mitscherlich, and many others of his fellow-workers in science. These were the gift of his widow, in accordance with his own desire.

2

This idea was suggested by some remarks of Faraday to the Baroness Burdett Coutts.

3

Sir Roderick Murchison used to tell how he was attending Brande's lectures, when one day, the Professor being absent, his assistant took his place, and lectured with so much ease that he won the complete approval of the audience. This, he said, was Faraday's first lecture at the Royal Institution.

4

The laboratory note-book shows that at this very time he was making a long series of commercial analyses of saltpetre for Mr. Brande.

5

The following anecdote has been sent me on the authority of Mr. Benjamin Abbott: – "Sergeant Anderson was engaged to attend to the furnaces in Mr. Faraday's researches on optical glass in 1828, and was chosen simply because of the habits of strict obedience his military training had given him. His duty was to keep the furnaces always at the same heat, and the water in the ashpit always at the same level. In the evening he was released, but one night Faraday forgot to tell Anderson he could go home, and early next morning he found his faithful servant still stoking the glowing furnace, as he had been doing all night long." A more probable and better authenticated version of this story is that after nightfall Anderson went upstairs to Faraday, who was already in bed, to inquire if he was to remain still on duty.

6

One evening, when the Rev. A. J. D'Orsey was lecturing "On the Study of the English Language," he mentioned as a common vulgarism that of using "don't" in the third person singular, as "He don't pay his debts." Faraday exclaimed aloud, "That's very wrong."

7

The St. Paul's Magazine, June 1870.

8

British Quarterly Review, April 1868.

9

See Appendix.

10

No wonder the celebrated electrician P. Riess, of Berlin, once addressed a long letter to him as "Professor Michael Faraday, Member of all Academies of Science, London."

11

Bacon's "Novum Organum," i. 1.

12

Bence Jones has used the Greek ἀγάπη; and it was just this ideal of Christian love which Faraday set before himself.

13

For this anecdote, and some others in inverted commas, I am indebted to Mr. Frank Barnard.

14

In another letter that Lady Burdett Coutts has kindly sent me, Faraday says: "We had your box once before, I remember, for a pantomime, which is always interesting to me because of the immense concentration of means which it requires." In a third he makes admiring comments on Fechter.

15

I myself once heard this advanced by an infidel lecturer on Paddington Green.

16

"Electrical Researches," Series XV.

17

"Analogies in the Progress of Nature and Grace," p. 121.

18

"Mittheilungen aus dem Reisetagebuche eines deutschen Naturforschers," p. 275.

19

Since the publication of the first edition I have been struck with how precisely his practice corresponded with his precept in the introduction to his book on "Chemical Manipulation: " – "When an experiment has been devised, its general nature and principles arranged in the mind, and the causes to be brought into action, with the effect to be expected, properly considered, then it has to be performed. The ultimate objects of an experiment, and also the particular contrivance or mode by which the results are to be produced, being mental, there remains the mere performance of it, which may properly enough be expressed by the term manipulation.

"Notwithstanding this subordinate character of manipulation, it is yet of high importance in an experimental science, and particularly in chemistry. The person who could devise only, without knowing how to perform, would not be able to extend his knowledge far, or make it useful; and where every doubt or question that arises in the mind is best answered by the result of an experiment, whatever enables the philosopher to perform the experiment in the simplest, quickest, and most direct manner, cannot but be esteemed by him as of the utmost value."

20

Punch's cartoon next week represented Professor Faraday holding his nose, and presenting his card to Father Thames, who rises out of the unsavoury ooze.

21

Since writing the above I have come across a letter written by Faraday in answer to one by Captain Welier as far back as 13th Sept. 1839, in which he pointed out the mal-adjustment of the dioptric apparatus at Orfordness. In July of the following year he made lengthy suggestions to the Trinity House, in which he proposed using a flat white circle or square, half an inch across, on a piece of black paper or card, as a "focal object." This was to be looked at from outside, in order to test the regularity of the glass apparatus. He also suggested observations on the divergence by looking at this white circle at a distance of twenty feet at most. Another plan he proposed was that of lighting the lamp and putting up a white screen outside. These methods of examining he carried out very shortly afterwards at Blackwall, on French and English refractors, but it seems never to have occurred to him to place his eye in the focus, or in any other manner to observe the course of the rays from inside the apparatus.

22

Dr. Scoffern, Belgravia, October 1867.

23

Mr. Barrett, Nature, Sept. 19, 1872.

24

A good instance of his caution in drawing conclusions is contained in one of his letters to me: —

"Royal Institution of Great Britain,

"2 July, 1859.

"My dear Gladstone,

"Although I have frequently observed lights from the sea, the only thing I have learnt in relation to their relative brilliancy is that the average of a very great number of observations would be required for the attainment of a moderate approximation to truth. One has to be some miles off at sea, or else the observation is not made in the chief ray, and then one does not know the state of the atmosphere about a given lighthouse. Strong lights like that of Cape Grisnez have been invisible when they should have been strong; feeble lights by comparison have risen up in force when one might have expected them to be relatively weak; and after inquiry has not shown a state of the air at the lighthouse explaining such differences. It is probable that the cause of difference often exists at sea.

"Besides these difficulties there is that other great one of not seeing the two lights to be compared in the field of view at the same time and same distance. If the eye has to turn 90° from one to the other, I have no confidence in the comparison; and if both be in the field of sight at once, still unexpected and unexplained causes of difference occur. The two lights at the South Foreland are beautifully situated for comparison, and yet sometimes the upper did not equal the lower when it ought to have surpassed it. This I referred at the time to an upper stratum of haze; but on shore they knew nothing of the kind, nor had any such or other reason to expect particular effects.

"Ever truly yours,

"M. Faraday."

As an instance of his unwillingness to commit himself to an opinion unless he was sure about it, may be cited a letter he wrote to Sir G. B. Airy, the Astronomer Royal, who asked for his advice in regard to the material of which the national standard of length should be made: – "I do not see any reason why a pure metal should be particularly free from internal change of its particles, and on the whole should rather incline to the hard alloy than to soft copper, and yet I hardly know why. I suppose the labour would be too great to lay down the standard on different metals and substances; and yet the comparison of them might be very important hereafter, for twenty years seem to do or tell a great deal in relation to standard measures." Bronze was finally chosen.