полная версия

полная версияA Woman's Hardy Garden

Helena Rutherfurd Ely

A Woman's Hardy Garden

Dedication

TO THE BEST FRIEND OF MY GARDEN,WHO, WITH HEART AND HANDS,HAS HELPED TO MAKE ITWHAT IT ISPREFACE

This little book is only meant to tell briefly of a few shrubs, hardy perennials, biennials and annuals of simple culture. I send it forth, hoping that my readers may find within its pages some help to plant and make their gardens grow.

Meadowburn FarmOctober, 1902

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTIONLove of flowers and all things green and growing is with many men and women a passion so strong that it often seems to be a sort of primal instinct, coming down through generation after generation, from the first man who was put into a garden “to dress it and to keep it.” People whose lives, and those of their parents before them, have been spent in dingy tenements, and whose only garden is a rickety soap-box high up on a fire-escape, share this love, which must have a plant to tend, with those whose gardens cover acres and whose plants have been gathered from all the countries of the world. How often in summer, when called to town, and when driving through the squalid streets to the ferries or riding on the elevated road, one sees these gardens of the poor. Sometimes they are only a Geranium or two, or the gay Petunia. Often a tall Sunflower, or a Tomato plant red with fruit. These efforts tell of the love for the growing things, and of the care that makes them live and blossom against all odds. One feels a thrill of sympathy with the owners of the plants, and wishes that some day their lot may be cast in happier places, where they too may have gardens to tend.

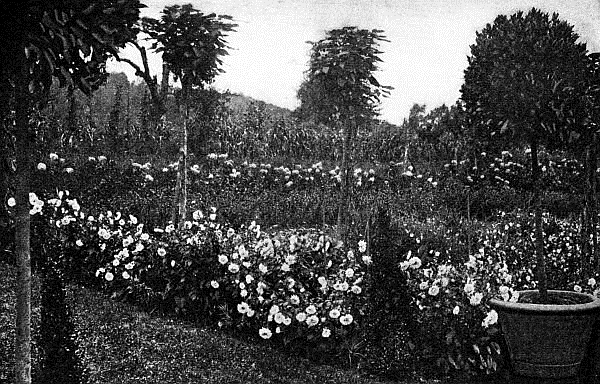

Broad grass walk

August twenty-fifth

It has always seemed to me that the punishment of the first gardener and his wife was the bitterest of all. To have lived always in a garden “where grew every tree pleasant to the sight and good for food,” to have known no other place, and then to have been driven forth into the great world without hope of returning! Oh! Eve, had you not desired wisdom, your happy children might still be tilling the soil of that blessed Eden. The first woman longed for knowledge, as do her daughters of to-day. When the serpent said that eating of the forbidden fruit would make them “as gods,” what wonder that Eve forgot the threatening command to leave untouched the Tree of Life, and, burning to be “wise,” ate of the fateful apple and gave it to her Adam? And then, to leave the lovely place at the loveliest of all times in a garden, the cool of the day! Faint sunset hues tinting the sky, the night breeze gently stirring the trees, Lilies and Roses giving their sweetest perfume, brilliant Venus mounting her accustomed path, while the sleepy twitter of the birds alone breaks the silence. Then the voice of wrath, the Cherubim, the turning flaming sword!

Through trials and tribulations and hardly learned patience, I have gained some of the secrets of many of our best hardy flowering plants and shrubs. Many friends have asked me to tell them when to plant or transplant, when to sow this or that seed, and how to prepare the beds and borders; in fact, this has occurred so often that it has long been in my mind to write down what I know of hardy gardening, that other women might be helped to avoid the experiments and mistakes I have made, which only served to cause delay.

But just this “please write it down,” while sounding so easy and presenting to the mind such a fascinating picture of a well-printed, well-illustrated and prettily bound book on the garden, is quite a different matter to one who has never written. When you diffidently try to explain the chaos in your brain, family and friends say, “Oh! never mind; just begin.” That often-quoted “premier pas!”

To-day is the first snow-storm of the winter, and, while sitting by the fireside, my thoughts are so upon my garden, wondering if this or that will survive, and whether the plants remember me, that it seems as though to-day I could try that first dreaded step.

Living all my life, six months and sometimes more of each year, in the country, – real country on a large farm, – I have from childhood been more than ordinarily interested in gardening. Surrounded from babyhood with horses and dogs, my time as a little girl was spent out of doors, and whenever I could escape from a patient governess, whose eyes early became sad because of the difficulties of her task, I was either riding a black pony of wicked temper, or was to be found in a lovely garden with tall Arborvitæ hedges and Box-edged walks, in the company of an old gardener, one of my very best friends, who for twenty years ruled master and mistress, as well as garden and graperies. Under this old gardener, I learned, even as a child, to bud Roses and fruit trees, and watched the transplanting of seedlings and making of slips; watched, too, the trimming of grape-vines, fruit trees and shrubs; so that while still very young I knew more than many an older person of practical garden work. Then, as I grew older, the interests of a gay girl, and, later, the claims of early married life and the care of two fat and fascinating babies, absorbed my time and thoughts to the exclusion of the garden. But as the babies grew into a big boy and girl, the garden came to the front again, and, for more than a dozen years now, it has been my joy, – joy in summer when watching the growth and bloom, and joy in winter when planning for the spring and summer’s work. There is pleasure even in making lists, reading catalogues of plants and seeds, and wondering whether this year my flowers will be like the pictured ones, and always, in imagination, seeing how the sleeping plants will look when robed in fullest beauty.

HARDY GARDENING AND THE PREPARATION OF THE SOIL

CHAPTER II

HARDY GARDENING AND THE PREPARATION OF THE SOILIt has not been all success. I have had to learn the soil and the location best suited to each plant; to know when each bloomed and which lived best together. Mine is a garden of bulbs, annuals, biennials and hardy perennials; in addition to which there are Cannas, Dahlias and Gladioli, whose roots can be stored, through the winter, in a cellar. All the rest of the garden goes gently to sleep in the autumn, is well covered up about Thanksgiving time, and slumbers quietly through the winter; until, with the first spring rains and sunny days, the plants seem fairly to bound into life again, and the never-ceasing miracle of nature is repeated before our wondering eyes.

I have no glass on my place, not even a cold-frame or hot-bed. Everything is raised in the open ground, except the few bedding plants mentioned whose roots are stored through the winter. Therefore, mine can truly be called a hardy garden, and is the only one I know at all approaching it in size and quantity of flowers raised, where similar conditions exist.

A shady garden walk

May thirty-first

I have observed that, with few exceptions, the least success with hardy perennials is found in the gardens of those of my friends whose gardeners are supposed to be the best, because paid the most. These men will grow wonderful Roses, Orchids, Carnations, Grapes, etc., under glass, and will often have fine displays of Rhododendrons. But to most of them the perennial or biennial plant, the old friend blossoming in the same place year after year, is an object unworthy of cultivation. Their souls rejoice in the bedding-out plant, which must be yearly renewed, and which is beautiful for so short a time, dying with the early frost, I was astounded last summer on visiting several fine places, where the gardeners were considered masters of their art, to see the poor planting of perennials and annuals. I recall particularly two Italian gardens, perfectly laid out by landscape gardeners, but which amounted to nothing because the planting was insufficient, – here a Phlox, there a Lily, then a Rose, with perhaps a Larkspur or a Marigold, all rigidly set out in single plants far apart, with nothing in masses, and no colour effects.

To attain success in growth, as well as in effect, plants must be so closely set that when they are developed no ground is to be seen. If so placed, their foliage shades the earth, and moisture is retained. In a border planted in this way, individual plants are far finer than those which, when grown, are six inches or a foot apart.

First of all in gardening, comes the preparation of the soil. Give the plants the food they need and plenty of water, and the blessed sunlight will do the rest. It is wonderful what can be done with a small space, and how from April to November there can always be a mass of bloom. I knew of one woman’s garden, in a small country town, – house and ground only covering a lot hardly fifty by one hundred feet, – where, with the help of a man to work for her one day in the week and perhaps for a week each spring and fall, she raises immense quantities of flowers, both perennials and annuals. For six months of the year she has always a dozen vases full in the house, and plenty to give away. More than half the time her little garden supplies flowers for the church, while others in the same village owning large places and employing several men “have really no flowers.”

I remember returning once from a two weeks’ trip, to find that my entire crop of Asters had been destroyed by a beetle. It was a horrid black creature about an inch long, which appeared in swarms, devoured all the plants and then disappeared, touching nothing else. Such a thing had never before happened in my garden. One of the men had sprayed them with both slug-shot and kerosene emulsion to no effect, – and so no Asters. My friend with the little garden heard me bemoaning my loss, and the next day sent me, over the five intervening miles, a hamper – almost a small clothes-basket – full of the beautiful things. It quite took my breath away. I wondered how she could do it, and thought she must have given me every one she had. Yet, upon driving over in hot haste to pour out thanks and regrets, lo! there were Asters all a-blow in such quantities in her garden that it seemed as if none had been gathered.

Except by the sea-coast, our dry summers, with burning sun and, in many places, frequent absence of dew, are terribly hard on a garden; but with deep, rich soil, and plenty of water and proper care, it will yield an almost tropical growth. Therefore, whenever a bed or border is to be made, make it right. Unless one is willing to take the trouble properly to prepare the ground, there is no use in expecting success in gardening. I have but one rule: stake out the bed, and then dig out the entire space two feet in depth. Often stones will be found requiring the strength and labor of several men, with crowbars and levers, to remove them; often there will be rocks that require blasting. Stones and earth being all removed, put a foot of well-rotted manure in the bottom; then fill up with alternate layers, about four inches each, of the top soil, taken out of the first foot dug up, and of manure. Fill the bed or border very full, as it will sink with the disintegration of the manure. Finish off the top with three inches of soil. Then it is ready for planting. If the natural soil is stiff or clayey, put it in a heap and mix with one-fourth sand, to lighten it, before returning to the bed. Thus prepared, it will retain moisture, and not pack and become hard.

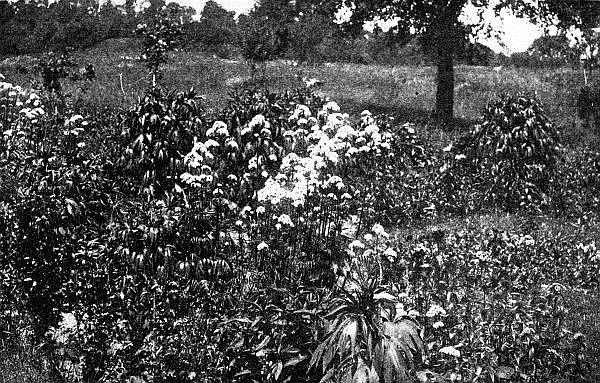

Asters blooming in a border

September fifteenth

LAYING OUT A GARDEN AND BORDERS AROUND THE HOUSE

A clump of Valerian

June sixth

CHAPTER III

LAYING OUT A GARDEN AND BORDERS AROUND THE HOUSEPerplexities assail a would-be gardener on every side, from the day it is decided to start a garden. The most attractive books on the subject are English; and yet, beyond the suggestions for planting, and the designs given in the illustrations, not much help is to be derived in this latitude from following their directions. In England the climate, which is without great extremes of heat and cold, and the frequent rains, with the soft moist atmosphere, not only enable the English gardener to accomplish what would be impossible for us, but permit him to grow certain flowers out of doors that here must be housed in the winter. Daffodils and Narcissi bloom in England, near the coast, at the end of February and early in March, – Lilies-of-the-Valley in March. Many Roses live out of doors that would perish here during our winters. Gardening operations are begun there much earlier than in this part, at least, of the United States, and many of the methods for culture differ from those employed here. In England there is excess of moisture; therefore, care in securing good drainage is essential, while here, except in low places near streams, special provision for drainage is rarely necessary. It is more important to have a deep, rich preparation of the soil, so that plants may not be dried out. A serious part of the gardener’s work during the average summer consists in judicious watering of the garden.

One writer will say that this or that plant should have sun, another that it does best in the shade. One advocates a rich soil, another a light sandy soil; so that after all, in gardening, as in all else in life, experience is the best teacher, either your own or that of others who have already been successful under similar conditions.

A garden is almost sure to be gradually increased in size, and its capacity limited only by the grounds of the owner and his pocket-book. The possibilities and capabilities of a couple of acres are great, and will give the owner unlimited pleasure and occupation.

Individuality is one of the most marked of American characteristics; hence, in making a place, whether it is big or little, the tastes and individuality of the owner will generally direct his efforts, and no hard and fast rules can be given.

In starting a garden, the first question, of course, is where to plant. If you are a beginner in the art, and the place is new and large, go to a good landscape gardener and let him give advice and make you a plan. But don’t follow it; at least not at once, nor all at one time. Live there for a while, until you yourself begin to feel what you want, and where you want it. See all the gardens and places you can, and then, when you know what you want, or think you do, start in.

The relation of house to grounds must always be borne in mind, and simplicity in grounds should correspond with that of the house. A craze for Italian gardens is seizing upon people generally, regardless of the architecture of their houses. To my mind, an Italian garden, with its balustrades, terraces, fountains and statues, is as inappropriate for surrounding a colonial or an ordinary country house as would be a Louis XV drawing-room in a farm-house.

Rhododendron maximum and Ferns along north side of house, with Ampelopsis Veitchii

July fourth

What is beautiful in one place becomes incongruous and ridiculous in another. Not long ago, a woman making an afternoon visit asked me to show her the gardens. Daintily balancing herself upon slippers with the highest possible heels, clad in a costume appropriate only for a fête at Newport, she strolled about. She thought it all “quite lovely” and “really, very nice,” but, at least ten times, while making the tour, wondered “Why in the world don’t you have an Italian garden?” No explanation of the lack of taste that such a garden would indicate in connection with the house, had any effect. The simple, formal gardens of a hundred years ago, with Box-edged paths, borders and regular Box-edged beds, are always beautiful, never become tiresome, and have the additional merit of being appropriate either to the fine country-place or the simple cottage.

Plan for a Small Plot

For a small plot of ground, like the one before mentioned, the plan of which is on page 24, the matter is simple, because of the natural limitations. I love to see a house bedded, as it were, in flowers. This is particularly suitable for the usual American country house, colonial in style, or low and rambling. Make a bed perhaps four feet wide along three sides of the house, – south, east and west. Close against the house plant the vines. Every one has an individual taste in vines, – more so, perhaps, than in any other ornamental growth. If the house be of stone, and the climate not too severe, nothing is more beautiful than the English Ivy. It flourishes as far north as Princeton, New Jersey. I have never grown it, fearing it would be winter-killed.

Ampelopsis Veitchii, sometimes called Boston Ivy, grows rapidly, clinging closely to the wall and turning a dark red in the autumn, and is most satisfactory.

The Virginia Creeper, and the Trumpet Creeper, with its scarlet flowers, are both beautiful, perfectly hardy, and of rapid growth. All of these vines cling to stone and wood, and, beyond a little help for the first two or three feet, need not be fastened to the house. Care must be taken to prevent the vines growing too thickly to admit sun and air to the house.

If the house be of wood, the question of repainting must be considered. Both the White and the Purple Wistaria, which can be twined about heavy wire and fastened at the eaves, Rambler Roses and Honeysuckles may be grown. They can be laid down, to permit painting. But, if the house be of wood and well covered with vines, put off the evil day of painting until it can be deferred no longer, and then have it done early in November. Never, never permit it to be done in the spring, or before November, unless you would take the risk of killing the vines or of losing at least a season’s growth. The house surrounded by my gardens is colonial, something over a hundred and fifty years old, stern and very simple. Tall locusts, towering above the roof, and vines that cover it from ground to eaves, have taken away its otherwise puritanical and somewhat uncompromising aspect. These vines are mostly the ordinary Virginia Creeper, which I had dug from the woods and planted when the first fat baby was two months old. Now their main trunks are, in places, as large as my arm. They have never been laid down. Whenever the house has been repainted, I have been constantly by, and admonished the men to gently lift the heavy branches while painting under them, and not to paint the light tendrils. When the master-painter has remonstrated, that it was not a “good job” and took three times as long as if the vines were laid down, my reply has been, that “three times” was nothing in comparison with the years it had taken to grow them, and that stunting or killing the vines could never be a “good job.”

Arch over rose-walk, covered with Golden Honeysuckle and Clematis paniculata

September fifteenth

Among the creepers are the Crimson Rambler Rose and the Honeysuckle. In three years the Roses have grown above the second-story windows.

Clematis paniculata, with its delicate foliage and mass of starry bloom in early autumn, is particularly good to plant by veranda posts in connection with other vines. It grows luxuriantly and is absolutely hardy. The large white-flowered Henryi and purple-flowered Jackmani Clematis, though of slow growth, should always have a place, either about a veranda, a summer-house or a trellis, for the sake of their beautiful flowers.

While waiting for the hardy vines to make their first year’s growth, the seeds of the Japanese Morning-Glory, the Japanese Moonflower and Cobœa scandens may be planted. All of these will grow at least ten feet in a summer, and cover the bare places. But I would not advise sowing them among the hardy vines, except the first summer. In their luxuriance they may suffocate the Roses and Clematis. The seeds of the Moonflower must be soaked in hot water, and left over night, before sowing. So much for the vines about a house.

In front of the vines, and on the south side in the same bed, plant masses of Hollyhocks, from eight to twelve in a bunch, and Rudbeckia in bunches of not more than five, as they grow so large. Hollyhocks and Rudbeckias plant two feet apart; they will grow to a solid mass. In front of these, again, put a clump of Phloxes, seven in a bunch, and Larkspur, Delphinium formosum being the best. On either side of the Delphinium have clumps of about a dozen Lilium candidum, which bloom at the same time. Edge the border with Sweet Williams, three kinds only, – white, pink and dark scarlet.

I should not advise making all the borders around a house alike. The easterly one will be most lovely if planted with tall ferns or brakes, taken from near some stream in early April, before they begin to grow. These will become about four feet high if you get good roots and keep them wet. Plant in among them everywhere Auratum Lilies, and you will have a border that will fill your heart with joy. On the north side of the house it is not possible to have much success with vines, as they need the sun. They will grow, but not with great luxuriance. Here plant two rows of the common Rhododendron maximum, which grows in our woods. I crave pardon for calling it “common,” since none that grows is more beautiful.

In front of these plant ferns of all kinds from the woods, and edge the border with Columbines. If these Rhododendrons do not grow in your vicinity, they can be ordered from a florist. In the hills, about five miles from us, acres of them grow wild, and twice a year I send my men with wagons to dig them up. They stand transplanting perfectly if care is taken to get all the roots, which is not difficult, as they do not grow deep. Keep them quite wet for a week after planting, and never let them get very dry. A good plan is to mulch them in early June to the depth of six inches or more with the clippings of the lawn grass, or with old manure. When once well rooted, the Rhododendrons will last a lifetime. They seem to bear transplanting at any season. Some think they do best if taken when in full bloom. I have always done this in April or late October, and, of a wagon-load transplanted last October, all have lived. Many of these were like trees, quite eight feet tall and too large to be satisfactory about the house, so they were set among the evergreens in a shrubbery.

Rhododendron maximum under a Cherry tree

July fourth

In cold localities, where the thermometer in winter falls below zero, Rhododendrons should be mulched with stable litter or leaves to the depth of one foot, after the ground has frozen. They should also have some protection from the winter sun, which can be easily given them by setting evergreen boughs of any kind into the ground here and there among them. Rhododendrons are as likely to be killed by alternate freezing and thawing of the ground in winter as by summer drought.

The lovely Azalea mollis, and many beautiful varieties of imported Rhododendrons, are usually described as “hardy,” but I cannot recommend them to those who live where the winters are severe. In such places their growth is very slow, and many perish.

Maidenhair, the most beautiful of the hardy ferns, is to be found in quantities in many of our woods, particularly those covering hillsides. Their favorite spot is along the edges of mountain brooks. I know such a hillside, where Maidenhair Ferns are superb. But nothing would induce me to venture there again, since I have been told it was infested with rattlesnakes, and that the woodchoppers kill a number of them every year. This fact, too, gives me scruples about sending the men to dig them up, although it is an awful temptation.