полная версия

полная версияThe Master of Mrs. Chilvers: An Improbable Comedy

Jerome K. Jerome

The Master of Mrs. Chilvers: An Improbable Comedy

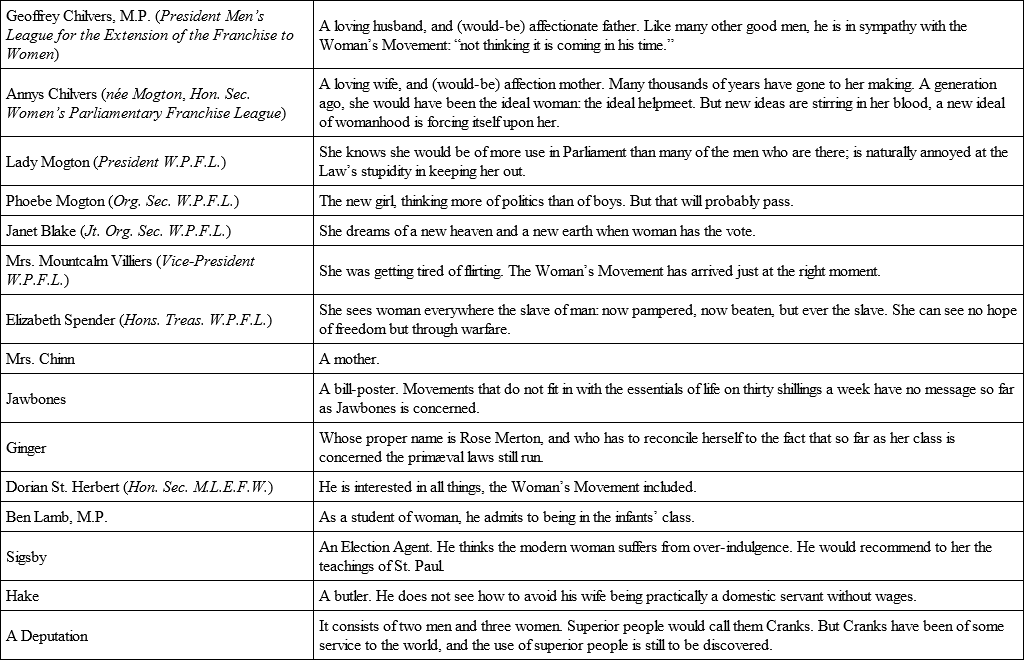

CHARACTERS IN THE PLAY

THE FIRST ACT

Scene: —Drawing-room, 91, Russell Square.

Time: —Afternoon(Mrs. Elizabeth Spender sits near the fire, reading a book. She is a tall, thin woman, with passionate eyes, set in an oval face of olive complexion; the features are regular and severe; her massive dark hair is almost primly arranged. She wears a tailor-made costume, surmounted by a plain black hat. The door opens and Phoebe enters, shown in by Hake, the butler, a thin, ascetic-looking man of about thirty, with prematurely grey hair. Phoebe Mogton is of the Fluffy Ruffles type, petite, with a retroussé nose, remarkably bright eyes, and a quantity of fluffy light hair, somewhat untidily arranged. She is fashionably dressed in the fussy, flyaway style. Elizabeth looks up; the two young women shake hands.)

Phoebe. Good woman. ’Tisn’t three o’clock yet, is it?

Elizabeth. About five minutes to.

Phoebe. Annys is on her way. I just caught her in time. (To Hake.) Put a table and six chairs. Give mamma a hammer and a cushion at her back.

Hake. A hammer, miss?

Phoebe. A chairman’s hammer. Haven’t you got one?

Hake. I’m afraid not, miss. Would a gravy spoon do?

Phoebe (To Elizabeth, after expression of disgust.) Fancy a house without a chairman’s hammer! (To Hake.) See that there’s something. Did your wife go to the meeting last night?

Hake (He is arranging furniture according to instructions.) I’m not quite sure, miss. I gave her the evening out.

Phoebe. “Gave her the evening out”!

Elizabeth. We are speaking of your wife, man, not your servant.

Hake. Yes, miss. You see, we don’t keep servants in our class. Somebody’s got to put the children to bed.

Elizabeth. Why not the man – occasionally?

Hake. Well, you see, miss, in my case, I rarely getting home much before midnight, it would make it so late. Yesterday being my night off, things fitted in, so to speak. Will there be any writing, miss?

Phoebe. Yes. See that there’s plenty of blotting-paper. (To Elizabeth.) Mamma always splashes so.

Hake. Yes, miss.

(He goes out.)Elizabeth. Did you ever hear anything more delightfully naïve? He “gave” her the evening out. That’s how they think of us – as their servants. The gentleman hasn’t the courage to be straightforward about it. The butler blurts out the truth. Why are we meeting here instead of at our own place?

Phoebe. For secrecy, I expect. Too many gasbags always about the office. I fancy – I’m not quite sure – that mamma’s got a new idea.

Elizabeth. Leading to Holloway?

Phoebe. Well, most roads lead there.

Elizabeth. And end there – so far as I can see.

Phoebe. You’re too impatient.

Elizabeth. It’s what our friends have been telling us – for the last fifty years.

Phoebe. Look here, if it was only the usual sort of thing mamma wouldn’t want it kept secret. I’m inclined to think it’s a new departure altogether.

(The door opens. There enters Janet Blake, followed by Hake, who proceeds with his work. Janet Blake is a slight, fragile-looking creature, her great dark eyes – the eyes of a fanatic – emphasise the pallor of her childish face. She is shabbily dressed; a plain, uninteresting girl until she smiles, and then her face becomes quite beautiful. Phoebe darts to meet her.) Good girl. Was afraid – I say, you’re wet through.

Janet. It was only a shower. The ’buses were all full. I had to ride outside.

Phoebe. Silly kid, why didn’t you take a cab?

Janet. I’ve been reckoning it up. I’ve been half over London chasing Mrs. Mountcalm-Villiers. Cabs would have come, at the very least, to twelve-and-six.

Phoebe. Well —

Janet (To Elizabeth.) Well – I want you to put me down as a contributor for twelve-and-six. (She smiles.) It’s the only way I can give.

Phoebe. (She is taking off Janet’s cloak; throws it to Hake.) Have this put somewhere to dry. (She pushes Janet to the fire.) Get near the fire. You’re as cold as ice.

Elizabeth. All the seats inside, I suppose, occupied by the chivalrous sex.

Janet. Oh, there was one young fellow offered to give me up his place, but I wouldn’t let him. You see, we’re claiming equality. (Smiles.)

Elizabeth. And are being granted it – in every direction where it works to the convenience of man.

Phoebe. (Laughs.) Is she coming – the Villiers woman?

Janet. Yes. I ran her down at last – at her dress-maker’s. She made an awful fuss about it, but I wouldn’t leave till she’d promised. Tell me, it’s something quite important, isn’t it?

Phoebe. I don’t know anything, except that I had an urgent telegram from mamma this morning to call a meeting of the entire Council here at three o’clock. She’s coming up from Manchester on purpose. (To Hake.) Mrs. Chilvers hasn’t returned yet, has she?

Hake. Not yet, miss. Shall I telephone —

Phoebe. (Shakes her head.) No; it’s all right. I have seen her. Let her know we are here the moment she comes in.

Hake. Yes, miss.

(He has finished the arrangements. The table has been placed in the centre of the room, six chairs round it, one of them being a large armchair. He has placed writing materials and a large silver gravy spoon. He is going.)

Phoebe. Why aren’t you sure your wife wasn’t at the meeting last night? Didn’t she say anything?

Hake. Well, miss, unfortunately, just as she was starting, Mrs. Comerford – that’s the wife of the party that keeps the shop downstairs – looked in with an order for the theatre.

Phoebe. Oh!

Hake. So I thought it best to ask no questions.

Phoebe. Thank you.

Hake. Thank you, miss.

(He goes out.)Elizabeth. Can nothing be done to rouse the working-class woman out of her apathy?

Phoebe. Well, if you ask me, I think a good deal has been done.

Elizabeth. Oh, what’s the use of our deceiving ourselves? The great mass are utterly indifferent.

Janet (She is seated in an easy-chair near the fire.) I was talking to a woman only yesterday – in Bethnal Green. She keeps a husband and three children by taking in washing. “Lord, miss,” she laughed, “what would we do with the vote if we did have it? Only one thing more to give to the men.”

Phoebe. That’s rather good.

Elizabeth. The curse of it is that it’s true. Why should they put themselves out merely that one man instead of another should dictate their laws to them?

Phoebe. My dear girl, precisely the same argument was used against the Second Reform Bill. What earthly difference could it make to the working men whether Tory Squire or Liberal capitalist ruled over them? That was in 1868. To-day, fifty-four Labour Members sit in Parliament. At the next election they will hold the balance.

Elizabeth. Ah, if we could only hold out that sort of hope to them!

(Annys enters. She is in outdoor costume. She kisses Phoebe, shakes hands with the other two. Annys’s age is about twenty-five. She is a beautiful, spiritual-looking creature, tall and graceful, with a manner that is at the same time appealing and commanding. Her voice is soft and caressing, but capable of expressing all the emotions. Her likeness to her younger sister Phoebe is of the slightest: the colouring is the same, and the eyes that can flash, but there the similarity ends. She is simply but well dressed. Her soft hair makes a quiet but wonderfully effective frame to her face.)

Annys. (She is taking off her outdoor things.) Hope I’m not late. I had to look in at Caxton House. Why are we holding it here?

Phoebe. Mamma’s instructions. Can’t tell you anything more except that I gather the matter’s important, and is to be kept secret.

Annys. Mamma isn’t here, is she?

Phoebe. (Shakes her head.) Reaches St. Pancras at two-forty. (Looks at her watch.) Train’s late, I expect.

(Hake has entered.)Annys. (She hands Hake her hat and coat.) Have something ready in case Lady Mogton hasn’t lunched. Is your master in?

Hake. A messenger came for him soon after you left, ma’am. I was to tell you he would most likely be dining at the House.

Annys. Thank you.

(Hake goes out.)Annys. (To Elizabeth.) I so want you to meet Geoffrey. He’ll alter your opinion of men.

Elizabeth. My opinion of men has been altered once or twice – each time for the worse.

Annys. Why do you dislike men?

Elizabeth. (With a short laugh.) Why does the slave dislike the slave-owner?

Phoebe. Oh, come off the perch. You spend five thousand a year provided for you by a husband that you only see on Sundays. We’d all be slaves at that price.

Elizabeth. The chains have always been stretched for the few. My sympathies are with my class.

Annys. But men like Geoffrey – men who are devoting their whole time and energy to furthering our cause; what can you have to say against them?

Elizabeth. Simply that they don’t know what they’re doing. The French Revolution was nursed in the salons of the French nobility. When the true meaning of the woman’s movement is understood we shall have to get on without the male sympathiser.

(A pause.)Annys. What do you understand is the true meaning of the woman’s movement?

Elizabeth. The dragging down of man from his position of supremacy. What else can it mean?

Annys. Something much better. The lifting up of woman to be his partner.

Elizabeth. My dear Annys, the men who to-day are advocating votes for women are doing so in the hope of securing obedient supporters for their own political schemes. In New Zealand the working man brings his female relations in a van to the poll, and sees to it that they vote in accordance with his orders. When man once grasps the fact that woman is not going to be his henchman, but his rival, men and women will face one another as enemies.

(The door opens. Hake announces Lady Mogton and Dorian St. Herbert. Lady Mogton is a large, strong-featured woman, with a naturally loud voice. She is dressed with studied carelessness. Dorian St. Herbert, K.C., is a tall, thin man, about thirty. He is elegantly, almost dandily dressed.)

Annys. (Kissing her mother.) Have you had lunch?

Lady Mogton. In the train.

Phoebe. (Who has also kissed her mother and shaken hands with St. Herbert.) We are all here except Villiers. She’s coming. Did you have a good meeting?

Lady Mogton. Fairly. Some young fool had chained himself to a pillar and thrown the key out of window.

Phoebe. What did you do?

Lady Mogton. Tied a sack over his head and left him there.

(She turns aside for a moment to talk to St. Herbert, who has taken some papers from his despatch-box.)

Annys. (To Elizabeth.) We must finish out our talk some other time. You are quite wrong.

Elizabeth. Perhaps.

Lady Mogton. We had better begin. I have only got half an hour.

Janet. I saw Mrs. Villiers. She promised she’d come.

Lady Mogton. You should have told her we were going to be photographed. Then she’d have been punctual. (She has taken her seat at the table. St. Herbert at her right.) Better put another chair in case she does turn up.

Janet. (Does so.) Shall I take any notes?

Lady Mogton. No. (To Annys.) Give instructions that we are not to be interrupted for anything.

(Annys rings bell.)St. Herbert. (He turns to Phoebe, on his right.) Have you heard the latest?

There was an old man of Hong Kong,Whose language was terribly strong.(Enter Hake. He brings a bottle and glass, which he places.)

Annys. Oh, Hake, please, don’t let us be interrupted for anything. If Mrs. Mountcalm-Villiers comes, show her up. But nobody else.

Hake. Yes, ma’am.

(Hake goes out.)St. Herbert. (Continuing.)

It wasn’t the wordsThat frightened the birds,’Twas the ’orrible double-entendre.Lady Mogton. (Who has sat waiting in grim silence.) Have you finished?

St. Herbert. Quite finished.

Lady Mogton. Thank you. (She raps for silence.) You will understand, please, all, that this is a private meeting of the Council. Nothing that transpires is to be allowed to leak out. (There is a murmur.) Silence, please, for Mr. St. Herbert.

St. Herbert. Before we begin, I should like to remind you, ladies, that you are, all of you, persons mentally deficient —

(The door opens. Mrs. Mountcalm-Villiers enters, announced by Hake. She is a showily-dressed, flamboyant lady.)

Mrs. Mountcalm-Villiers. I am so sorry. I have only just this minute – (She catches sight of St. Herbert.) You naughty creature, why weren’t you at my meeting last night? The Rajah came with both his wives. We’ve elected them, all three, honorary members.

Lady Mogton. Do you mind sitting down?

Mrs. Mountcalm-Villiers. Here, dear? (She takes the vacant chair.) So nice of you. I read about your meeting. What a clever idea!

Lady Mogton. (Cuts her short.) Yes. We are here to consider a very important matter. By way of commencement Mr. St. Herbert has just reminded us that in the eye of the law all women are imbeciles.

Mrs. Mountcalm-Villiers. I know, dear. Isn’t it shocking?

St. Herbert. Deplorable; but of course not your fault. I mention it because of its importance to the present matter. Under Clause A of the Act for the Better Regulation, &c., &c., all persons “mentally deficient” are debarred from becoming members of Parliament. The classification has been held to include idiots, infants, and women.

(An interruption. Lady Mogton hammers.)Bearing this carefully in mind, we proceed. (He refers to his notes.) Two years ago a bye-election took place for the South-west division of Belfast.

Mrs. Mountcalm-Villiers. My dear, may I? It has just occurred to me. Why do we never go to Ireland?

Lady Mogton. For various sufficient reasons.

Mrs. Mountcalm-Villiers. So many of the Irish members have expressed themselves quite sympathetically.

Lady Mogton. We wish them to continue to do so. (Turns to St. Herbert.) I’m sorry.

St. Herbert. A leader of the Orange Party was opposed by a Nationalist, and the proceedings promised to be lively. They promised for a while to be still livelier, owing to the nomination at the last moment of the local lunatic.

Phoebe. (To Annys.) This is where we come in.

St. Herbert. There is always a local lunatic, who, if harmless, is generally a popular character. James Washington McCaw appears to have been a particularly cheerful specimen. One of his eccentricities was to always have a skipping-rope in his pocket; wherever the traffic allowed it, he would go through the streets skipping. He said it kept him warm. Another of his tricks was to let off fireworks from the roof of his house whenever he heard of the death of anybody of importance. The Returning Officer refused his nomination – which, so far as his nominators were concerned, was intended only as a joke – on the grounds of his being by common report a person of unsound mind. And there, so far as South-west Belfast was concerned, the matter ended.

Phoebe. Pity.

St. Herbert. But not so far as the Returning Officer was concerned. McCaw appears to have been a lunatic possessed of means, imbued with all an Irishman’s love of litigation. He at once brought an action against the Returning Officer, his contention being that his mental state was a private matter, of which the Returning Officer was not the person to judge.

Phoebe. He wasn’t a lunatic all over.

St. Herbert. We none of us are. The case went from court to court. In every instance the decision was in favour of the Returning Officer. Until it reached the House of Lords. The decision was given yesterday afternoon – in favour of the man McCaw.

Elizabeth. Then lunatics, at all events, are not debarred from going to the poll.

St. Herbert. The “mentally deficient” are no longer debarred from going to the poll.

Elizabeth. What grounds were given for the decision?

St. Herbert. (He refers again to his notes.) A Returning Officer can only deal with objections arising out of the nomination paper. He has no jurisdiction to go behind a nomination paper and constitute himself a court of inquiry as to the fitness or unfitness of a candidate.

Phoebe. Good old House of Lords!

(Lady Mogton hammers.)Elizabeth. But I thought it was part of the Returning Officer’s duty to inquire into objections, that a special time was appointed to deal with them.

St. Herbert. He will still be required to take cognisance of any informality in the nomination paper or papers. Beyond that, this decision relieves him of all further responsibility.

Janet. But this gives us everything.

St. Herbert. It depends upon what you call everything. It gives a woman the right to go to the poll – a right which, as a matter of fact, she has always possessed.

Phoebe. Then why did the Returning Officer for Camberwell in 1885 —

St. Herbert. Because he did not know the law. And Miss Helen Taylor had not the means possessed by our friend McCaw to teach it to him.

Annys. (Rises. She goes to the centre of the room.)

Lady Mogton. Where are you going?

Annys. (She turns; there are tears in her eyes. The question seems to recall her to herself.) Nowhere. I am so sorry. I can’t help it. It seems to me to mean so much. It gives us the right to go before the people – to plead to them, not for ourselves, for them. (Again she seems to lose consciousness of those at the table, of the room.) To the men we will say: “Will you not trust us? Is it harm we have ever done you? Have we not suffered for you and with you? Were we not sent into the world to be your helpmeet? Are not the children ours as well as yours? Shall we not work together to shape the world where they must dwell? Is it only the mother-voice that shall not be heard in your councils? Is it only the mother-hand that shall not help to guide?” To the women we will say: “Tell them – tell them it is from no love of ourselves that we come from our sheltered homes into the street. It is to give, not to get – to mingle with the sterner judgments of men the deeper truths that God, through pain, has taught to women – to mingle with man’s justice woman’s pity, till there shall arise the perfect law – not made of man nor woman, but of both, each bringing what the other lacks.” And they will listen to us. Till now it has seemed to them that we were clamouring only for selfish ends. They have not understood. We shall speak to them of common purposes, use the language of fellow-citizens. They will see that we are worthy of the place we claim. They will welcome us as helpers in a common cause. They —

(She turns—the present comes back to her.)Lady Mogton. (After a pause.) The business (she dwells severely on the word) before the meeting —

Annys. (She resents herself meekly. Apologising generally.) I must learn to control myself.

Lady Mogton. (Who has waited.) – is McCaw versus Potts. Its bearing upon the movement for the extension of the franchise to women. My own view I venture to submit in the form of a resolution. (She takes up a paper on which she has been writing.) As follows: That the Council of the Woman’s Parliamentary Franchise League, having regard to the decision of the House of Lords in McCaw v. Potts —

St. Herbert. (Looking over.) Two t’s.

Lady Mogton. – resolves to bring forward a woman candidate to contest the next bye-election. (Suddenly to Mrs. Mountcalm-Villiers, who is chattering.) Do you agree or disagree?

Mrs. Mountcalm-Villiers. My dear! How can you ask? Of course we all agree. (To Elizabeth.) You agree, don’t you?

Elizabeth. Of course, even if elected, she would not be allowed to take her seat.

Phoebe. How do you know? Nothing more full of surprises than English law.

Lady Mogton. At the present stage I regard that point as immaterial. What I am thinking of is the advertisement. A female candidate upon the platform will concentrate the whole attention of the country on our movement.

St. Herbert. It might even be prudent – until you have got the vote – to keep it dark that you will soon be proceeding to the next inevitable step.

Elizabeth. You think even man could be so easily deceived!

St. Herbert. Man has had so much practice in being deceived. It comes naturally to him.

Elizabeth. Poor devil!

Lady Mogton. The only question remaining to be discussed is the candidate.

Annys. Is there not danger that between now and the next bye-election the Government may, having regard to this case, bring in a bill to stop women candidates from going to the poll?

St. Herbert. I have thought of that. Fortunately, the case seems to have attracted very little attention. If a bye-election occurred soon there would hardly be time.

Lady Mogton. It must be the very next one that does occur – wherever it is.

Janet. I am sure that in the East End we should have a chance.

Phoebe. Great Scott! Just think. If we were to win it!

St. Herbert. If you could get a straight fight against a Liberal I believe you would.

Annys. Why is the Government so unpopular?

St. Herbert. Well, take the weather alone – twelve degrees of frost again last night.

Janet. In St. George’s Road the sewer has burst. The water is in the rooms where the children are sleeping. (She clenches her hands.)

Mrs. Mountcalm-Villiers. (She shakes her head.) Something ought really to be done.

Lady Mogton. Has anybody any suggestion to make? – as regards the candidate. There’s no advantage in going outside. It will have to be one of ourselves.

Mrs. Mountcalm-Villiers. Won’t you, dear?

Lady Mogton. I shall be better employed organising. My own feeling is that it ought to be Annys. (To St. Herbert.) What do you think?

St. Herbert. Undoubtedly.

Annys. I’d rather not.

Lady Mogton. It’s not a question of liking. It’s a question of duty. For this occasion we shall be appealing to the male voter. Our candidate must be a woman popular with men. The choice is somewhat limited.

Elizabeth. No one will put up so good a fight as you.

Annys. Will you give me till this evening?

Lady Mogton. What for?

Annys. I should like to consult Geoffrey.

Lady Mogton. You think he would object?

Annys. (A little doubtfully.) No. But we have always talked everything over together.

Lady Mogton. Absurd! He’s one of our staunchest supporters. Of course he’ll be delighted.

Elizabeth. I think the thing ought to be settled at once.

Lady Mogton. It must be. I have to return to Manchester to-night. We shall have to get to work immediately.

St. Herbert. Geoffrey will surely take it as a compliment.

Janet. Don’t you feel that woman, all over the world, is calling to you?

Annys. It isn’t that. I’m not trying to shirk it. I merely thought that if there had been time – of course, if you really think —