полная версия

полная версияLife's Handicap: Being Stories of Mine Own People

‘He’s holding himself as tightly as ever he can,’ thought Spurstow. ‘What in the world is the matter with him? – Hummil!’

‘Yes,’ in a thick constrained voice.

‘Can’t you get to sleep?’

‘No.’

‘Head hot? ‘Throat feeling bulgy? or how?’

‘Neither, thanks. I don’t sleep much, you know.’

‘Feel pretty bad?’

‘Pretty bad, thanks. There is a tomtom outside, isn’t there? I thought it was my head at first… Oh, Spurstow, for pity’s sake give me something that will put me asleep, – sound asleep, – if it’s only for six hours!’ He sprang up, trembling from head to foot. ‘I haven’t been able to sleep naturally for days, and I can’t stand it! – I can’t stand it!’

‘Poor old chap!’

‘That’s no use. Give me something to make me sleep. I tell you I’m nearly mad. I don’t know what I say half my time. For three weeks I’ve had to think and spell out every word that has come through my lips before I dared say it. Isn’t that enough to drive a man mad? I can’t see things correctly now, and I’ve lost my sense of touch. My skin aches – my skin aches! Make me sleep. Oh, Spurstow, for the love of God make me sleep sound. It isn’t enough merely to let me dream. Let me sleep!’

‘All right, old man, all right. Go slow; you aren’t half as bad as you think.’

The flood-gates of reserve once broken, Hummil was clinging to him like a frightened child. ‘You’re pinching my arm to pieces.’

‘I’ll break your neck if you don’t do something for me. No, I didn’t mean that. Don’t be angry, old fellow.’ He wiped the sweat off himself as he fought to regain composure. ‘I’m a bit restless and off my oats, and perhaps you could recommend some sort of sleeping mixture, – bromide of potassium.’

‘Bromide of skittles! Why didn’t you tell me this before? Let go of my arm, and I’ll see if there’s anything in my cigarette-case to suit your complaint.’ Spurstow hunted among his day-clothes, turned up the lamp, opened a little silver cigarette-case, and advanced on the expectant Hummil with the daintiest of fairy squirts.

‘The last appeal of civilisation,’ said he, ‘and a thing I hate to use. Hold out your arm. Well, your sleeplessness hasn’t ruined your muscle; and what a thick hide it is! Might as well inject a buffalo subcutaneously. Now in a few minutes the morphia will begin working. Lie down and wait.’

A smile of unalloyed and idiotic delight began to creep over Hummil’s face. ‘I think,’ he whispered, – ‘I think I’m going off now. Gad! it’s positively heavenly! Spurstow, you must give me that case to keep; you – ’ The voice ceased as the head fell back.

‘Not for a good deal,’ said Spurstow to the unconscious form. ‘And now, my friend, sleeplessness of your kind being very apt to relax the moral fibre in little matters of life and death, I’ll just take the liberty of spiking your guns.’

He paddled into Hummil’s saddle-room in his bare feet and uncased a twelve-bore rifle, an express, and a revolver. Of the first he unscrewed the nipples and hid them in the bottom of a saddlery-case; of the second he abstracted the lever, kicking it behind a big wardrobe. The third he merely opened, and knocked the doll-head bolt of the grip up with the heel of a riding-boot.

‘That’s settled,’ he said, as he shook the sweat off his hands. ‘These little precautions will at least give you time to turn. You have too much sympathy with gun-room accidents.’

And as he rose from his knees, the thick muffled voice of Hummil cried in the doorway, ‘You fool!’

Such tones they use who speak in the lucid intervals of delirium to their friends a little before they die.

Spurstow started, dropping the pistol. Hummil stood in the doorway, rocking with helpless laughter.

‘That was awf’ly good of you, I’m sure,’ he said, very slowly, feeling for his words. ‘I don’t intend to go out by my own hand at present. I say, Spurstow, that stuff won’t work. What shall I do? What shall I do?’ And panic terror stood in his eyes.

‘Lie down and give it a chance. Lie down at once.’

‘I daren’t. It will only take me half-way again, and I shan’t be able to get away this time. Do you know it was all I could do to come out just now? Generally I am as quick as lightning; but you had clogged my feet. I was nearly caught.’

‘Oh yes, I understand. Go and lie down.’

‘No, it isn’t delirium; but it was an awfully mean trick to play on me. Do you know I might have died?’

As a sponge rubs a slate clean, so some power unknown to Spurstow had wiped out of Hummil’s face all that stamped it for the face of a man, and he stood at the doorway in the expression of his lost innocence. He had slept back into terrified childhood.

‘Is he going to die on the spot?’ thought Spurstow. Then, aloud, ‘All right, my son. Come back to bed, and tell me all about it. You couldn’t sleep; but what was all the rest of the nonsense?’

‘A place, – a place down there,’ said Hummil, with simple sincerity. The drug was acting on him by waves, and he was flung from the fear of a strong man to the fright of a child as his nerves gathered sense or were dulled.

‘Good God! I’ve been afraid of it for months past, Spurstow. It has made every night hell to me; and yet I’m not conscious of having done anything wrong.’

‘Be still, and I’ll give you another dose. We’ll stop your nightmares, you unutterable idiot!’

‘Yes, but you must give me so much that I can’t get away. You must make me quite sleepy, – not just a little sleepy. It’s so hard to run then.’

‘I know it; I know it. I’ve felt it myself. The symptoms are exactly as you describe.’

‘Oh, don’t laugh at me, confound you! Before this awful sleeplessness came to me I’ve tried to rest on my elbow and put a spur in the bed to sting me when I fell back. Look!’

‘By Jove! the man has been rowelled like a horse! Ridden by the nightmare with a vengeance! And we all thought him sensible enough. Heaven send us understanding! You like to talk, don’t you?’

‘Yes, sometimes. Not when I’m frightened. THEN I want to run. Don’t you?’

‘Always. Before I give you your second dose try to tell me exactly what your trouble is.’

Hummil spoke in broken whispers for nearly ten minutes, whilst Spurstow looked into the pupils of his eyes and passed his hand before them once or twice.

At the end of the narrative the silver cigarette-case was produced, and the last words that Hummil said as he fell back for the second time were, ‘Put me quite to sleep; for if I’m caught I die, – I die!’

‘Yes, yes; we all do that sooner or later, – thank Heaven who has set a term to our miseries,’ said Spurstow, settling the cushions under the head. ‘It occurs to me that unless I drink something I shall go out before my time. I’ve stopped sweating, and – I wear a seventeen-inch collar.’ He brewed himself scalding hot tea, which is an excellent remedy against heat-apoplexy if you take three or four cups of it in time. Then he watched the sleeper.

‘A blind face that cries and can’t wipe its eyes, a blind face that chases him down corridors! H’m! Decidedly, Hummil ought to go on leave as soon as possible; and, sane or otherwise, he undoubtedly did rowel himself most cruelly. Well, Heaven send us understanding!’

At mid-day Hummil rose, with an evil taste in his mouth, but an unclouded eye and a joyful heart.

‘I was pretty bad last night, wasn’t I?’ said he.

‘I have seen healthier men. You must have had a touch of the sun. Look here: if I write you a swingeing medical certificate, will you apply for leave on the spot?’

‘No.’

‘Why not? You want it.’

‘Yes, but I can hold on till the weather’s a little cooler.’

‘Why should you, if you can get relieved on the spot?’

‘Burkett is the only man who could be sent; and he’s a born fool.’

‘Oh, never mind about the line. You aren’t so important as all that. Wire for leave, if necessary.’

Hummil looked very uncomfortable.

‘I can hold on till the Rains,’ he said evasively.

‘You can’t. Wire to headquarters for Burkett.’

‘I won’t. If you want to know why, particularly, Burkett is married, and his wife’s just had a kid, and she’s up at Simla, in the cool, and Burkett has a very nice billet that takes him into Simla from Saturday to Monday. That little woman isn’t at all well. If Burkett was transferred she’d try to follow him. If she left the baby behind she’d fret herself to death. If she came, – and Burkett’s one of those selfish little beasts who are always talking about a wife’s place being with her husband, – she’d die. It’s murder to bring a woman here just now. Burkett hasn’t the physique of a rat. If he came here he’d go out; and I know she hasn’t any money, and I’m pretty sure she’d go out too. I’m salted in a sort of way, and I’m not married. Wait till the Rains, and then Burkett can get thin down here. It’ll do him heaps of good.’

‘Do you mean to say that you intend to face – what you have faced, till the Rains break?’

‘Oh, it won’t be so bad, now you’ve shown me a way out of it. I can always wire to you. Besides, now I’ve once got into the way of sleeping, it’ll be all right. Anyhow, I shan’t put in for leave. That’s the long and the short of it.’

‘My great Scott! I thought all that sort of thing was dead and done with.’

‘Bosh! You’d do the same yourself. I feel a new man, thanks to that cigarette-case. You’re going over to camp now, aren’t you?’

‘Yes; but I’ll try to look you up every other day, if I can.’

‘I’m not bad enough for that. I don’t want you to bother. Give the coolies gin and ketchup.’

‘Then you feel all right?’

‘Fit to fight for my life, but not to stand out in the sun talking to you. Go along, old man, and bless you!’

Hummil turned on his heel to face the echoing desolation of his bungalow, and the first thing he saw standing in the verandah was the figure of himself. He had met a similar apparition once before, when he was suffering from overwork and the strain of the hot weather.

‘This is bad, – already,’ he said, rubbing his eyes. ‘If the thing slides away from me all in one piece, like a ghost, I shall know it is only my eyes and stomach that are out of order. If it walks – my head is going.’

He approached the figure, which naturally kept at an unvarying distance from him, as is the use of all spectres that are born of overwork. It slid through the house and dissolved into swimming specks within the eyeball as soon as it reached the burning light of the garden. Hummil went about his business till even. When he came in to dinner he found himself sitting at the table. The vision rose and walked out hastily. Except that it cast no shadow it was in all respects real.

No living man knows what that week held for Hummil. An increase of the epidemic kept Spurstow in camp among the coolies, and all he could do was to telegraph to Mottram, bidding him go to the bungalow and sleep there. But Mottram was forty miles away from the nearest telegraph, and knew nothing of anything save the needs of the survey till he met, early on Sunday morning, Lowndes and Spurstow heading towards Hummil’s for the weekly gathering.

‘Hope the poor chap’s in a better temper,’ said the former, swinging himself off his horse at the door. ‘I suppose he isn’t up yet.’

‘I’ll just have a look at him,’ said the doctor. ‘If he’s asleep there’s no need to wake him.’

And an instant later, by the tone of Spurstow’s voice calling upon them to enter, the men knew what had happened. There was no need to wake him.

The punkah was still being pulled over the bed, but Hummil had departed this life at least three hours.

The body lay on its back, hands clinched by the side, as Spurstow had seen it lying seven nights previously. In the staring eyes was written terror beyond the expression of any pen.

Mottram, who had entered behind Lowndes, bent over the dead and touched the forehead lightly with his lips. ‘Oh, you lucky, lucky devil!’ he whispered.

But Lowndes had seen the eyes, and withdrew shuddering to the other side of the room.

‘Poor chap! poor old chap! And the last time I met him I was angry. Spurstow, we should have watched him. Has he – ?’

Deftly Spurstow continued his investigations, ending by a search round the room.

‘No, he hasn’t,’ he snapped. ‘There’s no trace of anything. Call the servants.’

They came, eight or ten of them, whispering and peering over each other’s shoulders.

‘When did your Sahib go to bed?’ said Spurstow.

‘At eleven or ten, we think,’ said Hummil’s personal servant.

‘He was well then? But how should you know?’

‘He was not ill, as far as our comprehension extended. But he had slept very little for three nights. This I know, because I saw him walking much, and specially in the heart of the night.’

As Spurstow was arranging the sheet, a big straight-necked hunting-spur tumbled on the ground. The doctor groaned. The personal servant peeped at the body.

‘What do you think, Chuma?’ said Spurstow, catching the look on the dark face.

‘Heaven-born, in my poor opinion, this that was my master has descended into the Dark Places, and there has been caught because he was not able to escape with sufficient speed. We have the spur for evidence that he fought with Fear. Thus have I seen men of my race do with thorns when a spell was laid upon them to overtake them in their sleeping hours and they dared not sleep.’

‘Chuma, you’re a mud-head. Go out and prepare seals to be set on the Sahib’s property.’

‘God has made the Heaven-born. God has made me. Who are we, to inquire into the dispensations of God? I will bid the other servants hold aloof while you are reckoning the tale of the Sahib’s property. They are all thieves, and would steal.’

‘As far as I can make out, he died from – oh, anything; stoppage of the heart’s action, heat-apoplexy, or some other visitation,’ said Spurstow to his companions. ‘We must make an inventory of his effects, and so on.’

‘He was scared to death,’ insisted Lowndes. ‘Look at those eyes! For pity’s sake don’t let him be buried with them open!’

‘Whatever it was, he’s clear of all the trouble now,’ said Mottram softly.

Spurstow was peering into the open eyes.

‘Come here,’ said he. ‘Can you see anything there?’

‘I can’t face it!’ whimpered Lowndes. ‘Cover up the face! Is there any fear on earth that can turn a man into that likeness? It’s ghastly. Oh, Spurstow, cover it up!’

‘No fear – on earth,’ said Spurstow. Mottram leaned over his shoulder and looked intently.

‘I see nothing except some gray blurs in the pupil. There can be nothing there, you know.’

‘Even so. Well, let’s think. It’ll take half a day to knock up any sort of coffin; and he must have died at midnight. Lowndes, old man, go out and tell the coolies to break ground next to Jevins’s grave. Mottram, go round the house with Chuma and see that the seals are put on things. Send a couple of men to me here, and I’ll arrange.’

The strong-armed servants when they returned to their own kind told a strange story of the doctor Sahib vainly trying to call their master back to life by magic arts, – to wit, the holding of a little green box that clicked to each of the dead man’s eyes, and of a bewildered muttering on the part of the doctor Sahib, who took the little green box away with him.

The resonant hammering of a coffin-lid is no pleasant thing to hear, but those who have experience maintain that much more terrible is the soft swish of the bed-linen, the reeving and unreeving of the bed-tapes, when he who has fallen by the roadside is apparelled for burial, sinking gradually as the tapes are tied over, till the swaddled shape touches the floor and there is no protest against the indignity of hasty disposal.

At the last moment Lowndes was seized with scruples of conscience. ‘Ought you to read the service, – from beginning to end?’ said he to Spurstow.

‘I intend to. You’re my senior as a civilian. You can take it if you like.’

‘I didn’t mean that for a moment. I only thought if we could get a chaplain from somewhere, – I’m willing to ride anywhere, – and give poor Hummil a better chance. That’s all.’

‘Bosh!’ said Spurstow, as he framed his lips to the tremendous words that stand at the head of the burial service.

After breakfast they smoked a pipe in silence to the memory of the dead. Then Spurstow said absently —

‘’Tisn’t in medical science.’

‘What?’

‘Things in a dead man’s eye.’

‘For goodness’ sake leave that horror alone!’ said Lowndes. ‘I’ve seen a native die of pure fright when a tiger chivied him. I know what killed Hummil.’

‘The deuce you do! I’m going to try to see.’ And the doctor retreated into the bath-room with a Kodak camera. After a few minutes there was the sound of something being hammered to pieces, and he emerged, very white indeed.

‘Have you got a picture?’ said Mottram. ‘What does the thing look like?’

‘It was impossible, of course. You needn’t look, Mottram. I’ve torn up the films. There was nothing there. It was impossible.’

‘That,’ said Lowndes, very distinctly, watching the shaking hand striving to relight the pipe, ‘is a damned lie.’

Mottram laughed uneasily. ‘Spurstow’s right,’ he said. ‘We’re all in such a state now that we’d believe anything. For pity’s sake let’s try to be rational.’

There was no further speech for a long time. The hot wind whistled without, and the dry trees sobbed. Presently the daily train, winking brass, burnished steel, and spouting steam, pulled up panting in the intense glare. ‘We’d better go on on that,’ said Spurstow. ‘Go back to work. I’ve written my certificate. We can’t do any more good here, and work’ll keep our wits together. Come on.’

No one moved. It is not pleasant to face railway journeys at mid-day in June. Spurstow gathered up his hat and whip, and, turning in the doorway, said —

‘There may be Heaven, – there must be Hell. Meantime, there is our life here. We-ell?’

Neither Mottram nor Lowndes had any answer to the question.

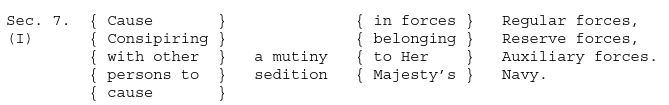

THE MUTINY OF THE MAVERICKS

When three obscure gentlemen in San Francisco argued on insufficient premises they condemned a fellow-creature to a most unpleasant death in a far country, which had nothing whatever to do with the United States. They foregathered at the top of a tenement-house in Tehama Street, an unsavoury quarter of the city, and, there calling for certain drinks, they conspired because they were conspirators by trade, officially known as the Third Three of the I.A.A. – an institution for the propagation of pure light, not to be confounded with any others, though it is affiliated to many. The Second Three live in Montreal, and work among the poor there; the First Three have their home in New York, not far from Castle Garden, and write regularly once a week to a small house near one of the big hotels at Boulogne. What happens after that, a particular section of Scotland Yard knows too well, and laughs at. A conspirator detests ridicule. More men have been stabbed with Lucrezia Borgia daggers and dropped into the Thames for laughing at Head Centres and Triangles than for betraying secrets; for this is human nature.

The Third Three conspired over whisky cocktails and a clean sheet of notepaper against the British Empire and all that lay therein. This work is very like what men without discernment call politics before a general election. You pick out and discuss, in the company of congenial friends, all the weak points in your opponents’ organisation, and unconsciously dwell upon and exaggerate all their mishaps, till it seems to you a miracle that the hated party holds together for an hour.

‘Our principle is not so much active demonstration – that we leave to others – as passive embarrassment, to weaken and unnerve,’ said the first man. ‘Wherever an organisation is crippled, wherever a confusion is thrown into any branch of any department, we gain a step for those who take on the work; we are but the forerunners.’ He was a German enthusiast, and editor of a newspaper, from whose leading articles he quoted frequently.

‘That cursed Empire makes so many blunders of her own that unless we doubled the year’s average I guess it wouldn’t strike her anything special had occurred,’ said the second man. ‘Are you prepared to say that all our resources are equal to blowing off the muzzle of a hundred-ton gun or spiking a ten-thousand-ton ship on a plain rock in clear daylight? They can beat us at our own game. ‘Better join hands with the practical branches; we’re in funds now. Try a direct scare in a crowded street. They value their greasy hides.’ He was the drag upon the wheel, and an Americanised Irishman of the second generation, despising his own race and hating the other. He had learned caution.

The third man drank his cocktail and spoke no word. He was the strategist, but unfortunately his knowledge of life was limited. He picked a letter from his breast-pocket and threw it across the table. That epistle to the heathen contained some very concise directions from the First Three in New York. It said —

‘The boom in black iron has already affected the eastern markets, where our agents have been forcing down the English-held stock among the smaller buyers who watch the turn of shares. Any immediate operations, such as western bears, would increase their willingness to unload. This, however, cannot be expected till they see clearly that foreign iron-masters are witting to co-operate. Mulcahy should be dispatched to feel the pulse of the market, and act accordingly. Mavericks are at present the best for our purpose. – P.D.Q.’

As a message referring to an iron crisis in Pennsylvania, it was interesting, if not lucid. As a new departure in organised attack on an outlying English dependency, it was more than interesting.

The second man read it through and murmured —

‘Already? Surely they are in too great a hurry. All that Dhulip Singh could do in India he has done, down to the distribution of his photographs among the peasantry. Ho! Ho! The Paris firm arranged that, and he has no substantial money backing from the Other Power. Even our agents in India know he hasn’t. What is the use of our organisation wasting men on work that is already done? Of course the Irish regiments in India are half mutinous as they stand.’

This shows how near a lie may come to the truth. An Irish regiment, for just so long as it stands still, is generally a hard handful to control, being reckless and rough. When, however, it is moved in the direction of musketry-firing, it becomes strangely and unpatriotically content with its lot. It has even been heard to cheer the Queen with enthusiasm on these occasions.

But the notion of tampering with the army was, from the point of view of Tehama Street, an altogether sound one. There is no shadow of stability in the policy of an English Government, and the most sacred oaths of England would, even if engrossed on vellum, find very few buyers among colonies and dependencies that have suffered from vain beliefs. But there remains to England always her army. That cannot change except in the matter of uniform and equipment. The officers may write to the papers demanding the heads of the Horse Guards in default of cleaner redress for grievances; the men may break loose across a country town and seriously startle the publicans; but neither officers nor men have it in their composition to mutiny after the continental manner. The English people, when they trouble to think about the army at all, are, and with justice, absolutely assured that it is absolutely trustworthy. Imagine for a moment their emotions on realising that such and such a regiment was in open revolt from causes directly due to England’s management of Ireland. They would probably send the regiment to the polls forthwith and examine their own consciences as to their duty to Erin; but they would never be easy any more. And it was this vague, unhappy mistrust that the I. A. A. were labouring to produce.

‘Sheer waste of breath,’ said the second man after a pause in the council, ‘I don’t see the use of tampering with their fool-army, but it has been tried before and we must try it again. It looks well in the reports. If we send one man from here you may bet your life that other men are going too. Order up Mulcahy.’

They ordered him up – a slim, slight, dark-haired young man, devoured with that blind rancorous hatred of England that only reaches its full growth across the Atlantic. He had sucked it from his mother’s breast in the little cabin at the back of the northern avenues of New York; he had been taught his rights and his wrongs, in German and Irish, on the canal fronts of Chicago; and San Francisco held men who told him strange and awful things of the great blind power over the seas. Once, when business took him across the Atlantic, he had served in an English regiment, and being insubordinate had suffered extremely. He drew all his ideas of England that were not bred by the cheaper patriotic prints from one iron-fisted colonel and an unbending adjutant. He would go to the mines if need be to teach his gospel. And he went as his instructions advised p.d.q. – which means ‘with speed’ – to introduce embarrassment into an Irish regiment, ‘already half-mutinous, quartered among Sikh peasantry, all wearing miniatures of His Highness Dhulip Singh, Maharaja of the Punjab, next their hearts, and all eagerly expecting his arrival.’ Other information equally valuable was given him by his masters. He was to be cautious, but never to grudge expense in winning the hearts of the men in the regiment. His mother in New York would supply funds, and he was to write to her once a month. Life is pleasant for a man who has a mother in New York to send him two hundred pounds a year over and above his regimental pay.