полная версия

полная версияBuxton and its Medicinal Waters

Robert Ottiwell Gifford-Bennet

Buxton and its Medicinal Waters

PREFACE

Knowing from long experience the powerful action exerted upon the human system by the Buxton Medicinal Thermal Water, and the unsatisfactory results arising from its indiscriminate and incautious use, either in the form of baths or by taking it internally, I have in the following pages, as briefly and succinctly as possible, endeavoured to make some practical suggestions for the guidance of those of my professional brethren who have had no opportunity of becoming personally acquainted with the Buxton Spa, with the hope that they may prove of service.

R. O. G. B.Tankerville House,

Buxton, May, 1892.

CHAPTER I.

TOPOGRAPHICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE

Situation – Altitude – Geology – Roman Baths – Climate and Temperature – Death Rate – Water-Supply – Rainfall – Drainage – Railway Communication – Public Buildings – Devonshire Hospital and Buxton Bath Charity – Visitors’ Accommodation – Antiquarian.

The ancient town of Buxton, which is situated upon the extreme western boundary of the county of Derby, at an elevation of 1,000ft. above the sea level, lies in a deep basin, having a subsoil of limestone and millstone grit, and is environed on every side by some of the most romantic and picturesque scenery in the High Peak, hill rising above hill in wild confusion, some attaining an altitude of from 1,900ft. to 2,000ft.

Buxton, or, as originally called, Bawkestanes, was occupied as a military station by the Romans, who, during their occupancy, constructed baths over the tepid water springs which issue through fissures in the limestone rock, where it comes in contact with the millstone grit, as was proved beyond doubt by the finding of Roman tiles (used in the construction of their baths) some years ago, when the present baths were under repair.

Although Buxton is situated at so great an altitude, the mean temperature for years past (owing, no doubt, in a great measure, to the taste displayed and forethought shown by the late Mr. Heacock, agent for many years to his Grace the Duke of Devonshire, in causing the surrounding hills to be well planted) has averaged about 44° Fahr., only a few degrees below that of some of the most frequented winter resorts in Great Britain. Such a temperature, however, may appear to some to militate against Buxton as a health resort except during the summer months, but it must be borne in mind that although the temperature may be said to be somewhat low (a necessity of its altitude), yet the atmosphere is especially pure and dry, and, like that of Davos Platz, plays no inconsiderable part in conducing to the highly-sanitary condition of the neighbourhood.

The healthiness of the Buxton district is borne out by the fact that the death-rate from zymotic disease is lower than that of most other localities in Great Britain, and that the average annual death-rate from all forms of disease is only (among the resident population) 10 in 1,000.

The air being so pure and dry exerts a most bracing and tonic effect, especially in cases where the system has become debilitated from any cause – anæmia, chlorosis, chronic liver and splenic disease, many forms of bronchial asthma, the first stage of tuberculosis of the lungs, and tubercular degeneration of the mesenteric glands in childhood, I have seen much benefitted by a short residence in the district. To the closely-confined and overworked residents in towns the crispness and buoyancy of the atmosphere impart a feeling of lightness and exhilaration rarely experienced except in a highland district, making mental and physical labour less irksome and life more enjoyable.

The water supply of Buxton is abundant, soft, and free from impurities, doubtless owing to its percolating through the great filter bed of sandstone to the north of the town, and issues in numerous springs far above any source of contamination from the inhabitants in the valley below.

It has been stated (and I think much to the prejudice of Buxton) that the rainfall of the High Peak, and especially of the Buxton district, is generally in excess of that of most of the other parts of Great Britain. Such an assertion is quite incorrect, as may be ascertained by a careful examination of the rainfall of other localities; although, as in all hilly districts, we must, on account of the attraction of the hills, expect a somewhat larger rainfall than on the plains. The annual average fall in the neighbourhood of Buxton amounts to about forty-nine inches, which is much less than that of many localities both in the Northern and Midland Counties. Even when there is an exceptionally heavy fall of rain the porous nature of the subsoil precludes the possibility of an accumulation of surface water to any great extent.

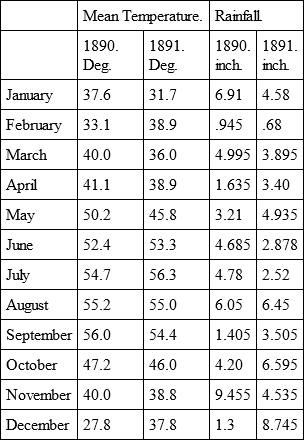

The following table shows the mean temperature and rainfall for 1890 and 1891, two years in which we have experienced a lower temperature and a greater rainfall than for some years past, which, I believe, has been the experience of most other parts of Britain during the same period: —

Mean temperature for 1890 = 44°.6; mean temperature for 1891 = 44°.4.

Rainfall for 1890 = 49.77in.; rainfall for 1891 = 52.718in.

Buxton being built in a valley inclining to the east, and upon the slopes of the adjoining hills to the south, west, and north, necessitates the convergence of its system of drainage into a main sewer, which is carried through the heart of the town to its outskirts, where the contents are discharged into tanks, and purified by a chemical process submitted to the town authorities by Dr. Thresh.

The natural incline upon which the town is built greatly facilitated the sewerage arrangements so ably planned and successfully carried out by the late Sir Robert Rawlinson.

Two lines of railway, the London and North-Western and Midland, whose stations are situated adjoining each other to the east end of the town, and between Buxton and Fairfield, afford every facility of communication with all parts of Great Britain and Ireland. The station of the East to West Railway now in process of formation will be in Higher Buxton, and will doubtless prove of much convenience to residents in that neighbourhood.

Visitors to Buxton, of all classes, will find ample and suitable accommodation in the numerous hotels, hydros, boarding-houses, and private apartments.

The Buxton Gardens’ Company’s Pavilion, Music Hall, and Theatre (where during the season the first artistes are engaged), lawn tennis, skating rink, golf, cricket, and football clubs, fishing, shooting, and hunting, provide varied amusements for all tastes.

Mail coaches and charabancs run daily (Sundays excepted) to either Bakewell, Haddon, Chatsworth, Matlock, Castleton, or Dove Dale, during the season. Private conveyances, riding and driving horses, are procurable by those wishing to visit the numerous places of interest in the neighbourhood or ride to hounds.

Buxton possesses some very handsome public and private buildings. The Crescent, perhaps one of the finest structures of its kind in Europe, has a frontage of 400ft. and a height of nearly 70ft., and is massive and bold in design. Above it is surmounted by an open battlement, which runs the whole of its length. In its centre the Devonshire coat of arms stands out in bold relief. Along the base of the building a wide open colonnade extends from one end to the other, and is a great convenience in going to and from the Baths and drinking fountain in wet weather, or as a promenade. It was originally intended for one hotel, but is now divided into two. In front is an open semicircular space, extending to the foot of St. Ann’s Cliff, an extensive piece of ground, tastefully laid out in terraces and public walks, some of which lead from terrace to terrace to the public drinking fountain at the base of the slope, and others to the plateau above, upon which stands the Town Hall, a handsome and substantially-built structure, recently erected, containing public and private offices, magisterial and assembly rooms, museum, free library, reading-room, &c.

The Devonshire Hospital is a large octagonal building surmounted by a lofty dome, and is situated at the foot of Corbar Hill, being a conspicuous object from all parts of the town. It was originally built for stabling in connection with the Crescent Hotel. Some years since the committee of the Buxton Bath Charity, being desirous of providing better accommodation for those seeking its aid, succeeded, mainly through the exertions of the late Mr. Wilmot, agent to his Grace the Duke of Devonshire, in obtaining the duke’s sanction to its conversion to its present use.

The structural alterations necessitated an outlay of between £30,000 and £40,000, towards which the committee of the Lancashire Cotton Fund contributed 24,000, in consideration of a first claim to the occupancy of 150 beds, the entire hospital accommodation being 300 beds.

The dome covers an area of nearly half an acre, and is said to be one of the largest in the world. Under its vast expanse between 5,000 and 6,000 people can assemble without overcrowding. A perfect echo, like that in the Baptistry at Pisa, is heard slightly away from beneath its centre.

The hospital is open to the inspection of visitors from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. at a small charge, which is appropriated for the purpose of purchasing books for the library, a great boon to the crippled patients.

The Palace Hotel, a large and imposing building, stands within its own grounds, beautifully situated and laid out, close to the London and North-Western and Midland Railway stations. Being elevated considerably above the town, a panoramic view of Higher and Lower Buxton, St. Ann’s Cliff, Broad Walk, the Crescent, and Buxton Gardens is obtained from its windows, and in the distance Axe Edge, 1,950ft., Harpur Hill, Diamond Hill (so-called from the Derbyshire diamond being found there), Solomon’s Temple, and Hindlow are in full view.

There are many other buildings worthy of notice, amongst which I may mention the churches of St. John and St. James, Pavilion Music Hall, Theatre, Union Club, the Buxton, Peak, and Haddon Grove Hydropathic Establishments. As the town is rapidly extending, many very pretty villas have recently sprung up in the park and neighbourhood, from whence are obtained the finest views of Buxton and the surrounding hills.

Buxton is well supplied with places of public worship, St. John’s, St. James’s, St. Anne’s, and Trinity, belonging to the Church of England; Hardwick Street Chapel, Congregationalists; the Park and Market Place Chapels, Wesleyan Methodists; London Road Chapel, Primitive Methodists; St. Ann’s Chapel, Terrace Road, Roman Catholic; and Harrington Road Chapel, Unitarian. The Presbyterians hold services every Sunday (during the season) in the Town Hall, morning and evening.

The staple industry of Buxton and the neighbourhood consists in the burning of limestone, and the manufacture of inlaid marble vases, tables, &c, some of which are tastefully designed, and form very elegant and beautiful ornamental decorations for the drawing-room, &c.

The naturalist, the botanist, and the geologist will find Nature’s hand-book, spread wide open over the hills and dales of the Peak, for their inspection. The archæologist and the antiquarian may wander to the top of Cowlow, Ladylow, Hindlow, Hucklow, or Grindlow, and picture in imagination the savage and warlike aborigines of the High Peak, wending their way up the precipitous sides of the hill, carrying their dead chieftain to his last resting-place on the mountain summit, where, placing him in a cyst, made of rough unhewn stones, they cover him up with earth, leaving his spirit to find its way to the happy hunting-grounds of the unseen; or watch the wild and barbarous rites performed by the Druidical priest within the precincts of Arbor Low Circle; or contemplate the savage hordes of Danes, as they lie encamped on the slopes of Priestcliff; or follow the footsteps of a hardy cohort of Rome’s picked soldiers, as it moves with steady precision through the High Peak Forest, and ascends the rugged side of Coomb’s Moss, to pitch a camp on the spur of Castle Naze.

The antiquarian may take his stand upon Mam-Tor, the mother rock, when the moon sheds her silvery light o’er Loosehill Mount, and, carrying his mind back into the past some 230 years, hear the bugle’s note as it sweeps through the Wynnats Pass, and is taken up by the Peverel Castle and transmitted onwards through the Vale of Hope, calling the hardy dalesmen to their midnight rendezvous, there to be instructed in the science of war, so as to enable them to protect their homes and families against the marauding myrmidons of a cruel, heartless, and unreliable king; or if the antiquarian seeketh a knowledge of the High Peak folk-lore, and feareth neither pixie or graymarie, he can, on a spring night, just as the moon has entered her last quarter, and the first note from the belfry of the chapel in the frith has proclaimed the arrival of midnight, take his stand upon Blentford’s Bluff and peer into the dark and sombre depths of Kinder, when he will hear the hooting of the barn owl on Anna rocks, the unearthly screech of the landrail as he ploughs his way through the unmown grass in search of his mate, the scream of the curlew and chatter of the red grouse as they take their flight from peak to peak, and see the fairy queen come forth from the mermaid’s cave in a shimmering light, followed by her maids, who dance a quadrille to the music of the spheres, and hear the wild blast of the hunter’s horn heralding the approach of the Gabriel hounds as they take their rapid course across the murky sky, and become lost in the unfathomable depths beyond the Scout.

CHAPTER II.

THE MEDICINAL WATERS AND THEIR ACTION

Physiological Functions in Healthy Individuals – Performance of the Physiological Functions in Health and Disease – Action of Oxygen upon the Nitrogenous and Non-nitrogenous Compounds – Origin of Calculi, Nodosities, and Tophi – Action of the Thermal Water upon the Great Emunctories – Chalybeate Water when used as a Douche, or Taken Internally – Analyses of the Waters – Selection of Buxton by the Romans – First Treatise upon the Buxton Spa, written by Dr. Jones in 1572 – Source and Nature of the Waters.

In a healthy individual, where the physiological functions are performed with exactitude and regularity, the elimination of the various effete matters, the result of waste of tissue, is uniform, and easily carried off out of the system by the skin, the kidneys, lungs, and bowels. The nitrogenous components become oxidised, and urea ultimately formed, which being very soluble is freely excreted by the sudorific glands in the perspiration, and by the kidneys in the urine. The non-nitrogenous compounds are also changed by the action of oxygen into carbonic acid, which is expelled from the system by the lungs. If the natural functions are not perfectly and with regularity performed, the balance of power must of necessity be lost, and disease engendered. The system then becomes charged with uric acid, which has a strong affinity for certain bases in the human organism, and forms salts either insoluble or only slightly so, which are with difficulty eliminated either by the skin or kidneys, and hence we have the formation of calculi in the bladder, nodosities on the joints, and tophi in the ears, indicating the uric acid diathesis.

The action of the Buxton nitrogenous thermal waters being solvent, stimulant, antacid, chologoge, diuretic, diaphoretic, and slightly purgative, restores the balance of power, not only by stimulating the gastric and hepatic organs to a correct performance of their normal functions, thus in conjunction with a strictly regulated diet (essential in all cases) cutting off the very source of the materies morbi, but also (when there) by eliminating it from the system by the great emunctories, viz., the skin, kidneys, lungs, and bowels. As the large proportion of invalid visitors to Buxton consist of those suffering from the uric acid or gouty diathesis, and rheumatism, and seek relief from the excruciating pains and cripplement incident to such diseases, the great attraction must of necessity be the medicinal waters, of which there are two kinds – the cold chalybeate or iron spring, and the natural thermal water. Of the former there are numerous springs in the neighbourhood of Buxton, but the only one now resorted to has been conveyed through pipes from a distance to a room adjoining the natural baths, and is used with much benefit in many forms of uterine disease as a douche. As such also it is prescribed in cases where the conjunctivæ are in a relaxed condition, consequent either upon rheumatic inflammation or local injuries. It should on no account be applied to the eyes until the inflammatory action has entirely subsided.

When drunk, one tumbler (twice or thrice daily after meals) may be taken by an adult with much advantage when suffering from anæmia, chlorosis, amenorrhœa, dysmenorrhœa, diabetes connected with the gouty diathesis, chronic cystitis, or general debility.

Although it may be classed as a mild chalybeate, I have frequently seen great benefit derived from its internal use (partly, no doubt, owing to the presence of sulphate of lime), especially in children of an undoubtedly strumous habit, where glandular swellings presented themselves in the neck, and the mesenteric glands were enlarged. In such cases, when taken regularly for some weeks (half a tumbler thrice daily after meals), the appetite returns, the digestive functions are improved, the glandular swellings subside, and the whole system becomes reinvigorated, so as to restore bloom to the cheek, brilliancy to the eyes, vigour to the limbs, and the natural buoyancy of spirit to childhood.

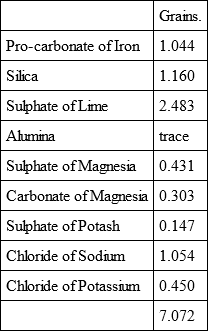

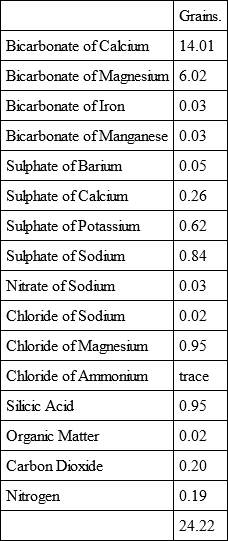

According to Dr. L. Playfair’s analysis in 1852, one gallon of the water was found to contain the following solid constituents: —

The thermal water, as before stated, arises from various fissures in the limestone rock, upon which formation the greater part of the town of Buxton is built. The flow is uniform (during the heat and drought of summer, and the cold and frost of winter) in volume, about 140 gallons per minute, in temperature 82 deg. Fahrenheit, and in solid constituents.

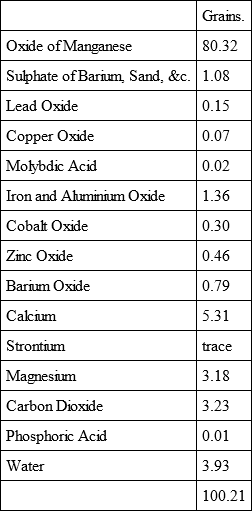

According to the latest analysis, made by Dr. Thresh in 1881, the following results were obtained. The mud which had settled around the mouths of the springs and floors of the tanks into which the water is conveyed consisted of —

The following is the result of his analysis of the water: —

There were also traces of lead, strontium, lithium, and phosphoric acid.

As the gas issued from the fissures in the limestone rock, it was found to consist of 99.22 grains of nitrogen, 0.88 grain of carbonic acid, and that held in solution in the water, 6.1 cubic inches nitrogen, 4.1 carbonic acid.

In comparing Dr. Thresh’s analysis with those previously made by Drs. Pearson, Muspratt, Sir Charles Scudamore, and Sir Lyon Playfair, it will be seen that a new constituent appears in the form of molybdinum, which, as mentioned above, was detected in the mud deposit at the bottom of the tanks into which the water is conveyed, as it issues directly from the springs. In other respects the analyses differ but slightly, nor does the efficacy of the water appear to have become less potent in alleviating or curing those diseases for which it is so deservedly celebrated.

The Romans, ever luxurious in their use of hot and tepid baths, doubtless selected the Buxton basin as a station, not merely from a military point of view, but on account of the thermal springs, the curative effects of which they would readily discover by receiving fresh energy to their wearied bodies, from the stimulating action of the water immediately upon taking a bath, as well as relief from many diseases, especially of a rheumatic character, to which their life of hardship and exposure rendered them so liable.

From the Roman period until about the year 1572 there is little or no recorded history of Buxton. About that time, however, a Dr. Jones wrote a treatise on the Buxton Spa, advocating its claims so forcibly to those afflicted with gout or rheumatism that ere long it became the resort of the elite in the fashionable world as well as the poor.

Dr. Jones mentions in his very interesting treatise that in his time Buxton was resorted to by large numbers of the poor and afflicted people from the surrounding districts. The indigence and deplorable condition of some of these people were so extreme and their numbers so great that to supply their necessities the whole of the “treasury of the bath fund was consumed, part of which the people of the adjoining chapelry of Fairfield claimed for the purpose of paying the stipend of their chaplain.” So great indeed became the grievance that they by petition sought the protection of Queen Elizabeth in the matter.

Dr. Jones, in his quaint and forcible way, writes in reference to the “treasury of the bath” fund: “If any think this magisterial imposing on people’s pockets let them consider their abilities and the sick poor’s necessities, and think whether they do not in idle pastimes throw away in vain twice as much yearly. It may entail the blessings of them who are ready to perish upon you, and will afford a pleasant after-reflection. God has given you physic for nothing; let the poor and afflicted (it may be members of Christ) have a little of your money, it may be better for your own health. Heaven might have put them in your room, and you in theirs, then a supply would have been acceptable to you.”

As the thermal water issues from the various fissures in the limestone rock, it is slightly alkaline, bright, sparkling, of a blueish tint, especially when collected in bulk, and soft and rather insipid in taste.

CHAPTER III.

THE BATHS AND MODE OF APPLICATION

Kinds of Baths – Natural and Hot – Action of Thermal Water upon the Skin – Natural Baths – Swimming and Plunge for Males and Females – Necessity of Caution in their Use – Importance of Time and Frequency in Taking the Baths – Directions During and After Bathing – Most Favourable Time for Taking Warm or Hot Baths – Directions for the Use of Half, Three-quarters, and Full Baths – Drowsiness after Bathing – Massage, When and How Used – When Baths Inadmissible – Hours for Drinking the Medicinal Waters – Diseases in which the Thermal Water should Not be Drunk.

There are two kinds of baths, viz., the natural and hot. The natural bath is so called because the water used in its formation is at the natural temperature, as it issues from the perforations in the floor of the baths. The stream being continuous and large in volume, an overflow is provided at the top of each bath, which not only secures constant change of water for the bathers, with corresponding purity, but much greater medicinal action upon the system.

The water renders the skin smooth and pliant, probably on account of its alkaline character and the large amount of free nitrogen suspended in it. Its alkalinity also saponifies the fatty acids on the surface of the body, cleanses and opens up the sudorific glands, and thus assists the free absorption of the nitrogen into the system. Brisk rubbing of the skin (whilst in the water) with the hands promotes a similar result.

Under the head of natural baths are included large swimming, plunge, or public baths for males and females, also private ones fitted up with every modern comfort and convenience, which are situated at the west-end of the Crescent, adjoining the pump-room or drinking fountain.

As the medicinal thermal water of Buxton is admitted to be very powerful in its action upon the human system, it is absolutely necessary that it should be used with the greatest care. I have known many accidents and even deaths take place from the incautious use of the natural baths by persons wilfully or negligently taking it in a totally unfit state of health, or by remaining in the water too long. When used as a bath at the natural temperature, the water is buoyant and emollient to the skin, and produces a sense of exhilaration both to the body and mind of the bather. But if indulged in too frequently or too long at one time, this beneficial effect is entirely lost, and instead of the glow of heat which ordinarily takes place directly after immersion, the surface of the body becomes chilled and covered with what is commonly called “goose” skin, a sense of oppression and discomfort ensues, erratic pains are developed, and the mind becomes greatly depressed. The bath, therefore, should not be taken more than two or at most three days consecutively, nor should the immersion extend beyond seven or eight minutes. It is well for the bather to take gentle exercise prior to entering the bath, in order that the surface of the body may not be chilled, but rather in a glow upon immersion. If after being in the water a few minutes a feeling of persistent chilliness ensues, the bather should leave the bath, get rubbed down with a hot rough towel, dress as quickly as possible, and then return home, where he should remain until reaction is perfectly established. When the natural bath is prescribed during the summer months, viz., from the commencement of June until the end of September or the first week in October, to those capable of locomotion the best time for bathing is from 6 to 8 o’clock a.m., but when incapable of walking from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. The bather should invariably (when taking a natural bath) lave the water over the face, neck, and chest, prior to plunging into it, and should not remain more than seven or eight minutes immersed, the two last minutes being occupied in applying the douche to the parts specially indicated in the doctor’s prescription. When a longer time is indulged in, frequently reaction does not take place, but chilliness and discomfort ensue, and the rheumatic pains are increased in severity rather than diminished. Energetic friction of the joints and surface of the body generally, with the hands beneath the water, should be resorted to, and gentle rubbing through a hot towel immediately upon leaving the bath, after which the bather should at once go to the drinking fountain and take the prescribed quantity of the thermal water. Instead, however, of at once returning home, if possible, a sharp brisk walk should be taken, so as to secure a full action upon the skin and kidneys. The bath may be taken between ten and one o’clock, or four and six, observing the same rules as to meals as given when speaking of the hot baths. The latter hours would apply to all cases except the very mildest during the winter months.