полная версия

полная версияWomen's Suffrage

Suffragists contend that a party which can do this cannot long maintain that women are by the mere fact of their sex unfit to be entrusted with a Parliamentary vote.

Even as long ago as his first Midlothian campaign, and before any definite political organisations for women existed, Mr. Gladstone had urged the women of his future constituency to come out and bear their part in the coming electoral struggle. Speaking to a meeting of women in Dalkeith in 1879 he said: —

"Therefore, I think in appealing to you ungrudgingly to open your own feelings and bear your own part in a political crisis like this, we are making no inappropriate demand, but are beseeching you to fulfil the duties which belong to you, which so far from involving any departure from your character as women, are associated with the fulfilment of that character and the performance of those duties, the neglect of which would in future years be a source of pain and mortification, and the accomplishment of which would serve to gild your future years with sweet remembrances and to warrant you in hoping that each in your own place and sphere has raised your voice for justice, and has striven to mitigate the sorrows and misfortunes of mankind."

In less ornate language Mr. Asquith, in January 1910, thanked the women of Fife for the aid they had given him and his cause during the election, and said that "their healthy influence on the masculine members of the community had had not a little to do with keeping things in a satisfactory condition."

The organised political work of women has grown since 1884, and has become so valuable that none of the parties can afford to do without it or to alienate it. Short of the vote itself this is one of the most important political weapons which can possibly have been put into our hands. At the outset, while the women's political societies were still young, and were hardly conscious of their power, the women's suffrage movement benefited greatly by their existence. If the Women's Liberal Federation had existed in 1884, the 104 Liberals who voted against Mr. Woodall's amendment would have probably decided that honesty was the best policy. In 1892 Sir Albert Rollit introduced a Women's Suffrage Bill, as nearly as possible on the lines of the Conciliation Bill of 1910-11. Before the second reading great efforts were made by the Liberal party machine to secure a crushing defeat for this Bill on its second reading: a confidential circular was sent out to all Liberal candidates in the Home Counties advising them not to allow Liberal women to speak on their platforms lest they should advocate "female suffrage." In addition to this, Mr. Gladstone was induced to write a letter addressed to Mr. Samuel Smith, M.P., against the Bill, in which he departed from his previous view that the political work done by women would be quite consistent with womanly character and duties, and would "gild their future years with sweet remembrances." He now said that voting would, he feared, "trespass upon their delicacy, their purity, their refinement, the elevation of their whole nature."

In addition to all this a whip was sent out signed by twenty members of Parliament, ten from each side of the House, earnestly beseeching members to be in their places when Sir Albert Rollit's Bill came on and to vote against the second reading. But when the division came, notwithstanding all the unusual efforts that had been made, it was only defeated by 23. A general election was known to be not very far off, and members who were expecting zealous and efficient support from women in their constituencies did not care to alienate it by denying to women the smallest and most elementary of political privileges. In surprising numbers (as compared with 1884) they stood to their guns, and though they did not save the Bill, the balance against it was so small that it was an earnest of future victory. This division in 1892 was the last time a Women's Suffrage Bill was defeated on a straight issue in the House of Commons. Mr. Faithfull Begg's Bill in 1897 was carried on second reading by 228 votes to 157. After this date direct frontal attacks on the principle of women's suffrage were avoided in the House of Commons. The anti-suffragists in Parliament used every possible trick and stratagem to prevent the subject being discussed and divided on in the House. In this they were greatly helped by Mr. Labouchere, to whom it was a congenial task to shelve the women's suffrage question. On one occasion he and his little group of supporters talked for hours about a Bill dealing with "verminous persons," because it stood before a Suffrage Bill, and he thus succeeded in preventing our Bill from coming before the House.

CHAPTER IV

WOMEN'S SUFFRAGE IN GREATER BRITAIN

"Wake up, Mother Country." – Speech by King George V. when Prince of Wales.

The debate on Sir Albert Rollit's Bill in 1892 brought out a full display of oratorical power from all quarters of the House, both for and against women's suffrage. Mr. James Bryce, Mr. Asquith, and Sir Henry James (afterwards Lord James) spoke against the Bill. Mr. Balfour, Mr. (now Lord) Courtney, and Mr. Wyndham supported it. When Mr. Bryce spoke he used the timid argument that women's suffrage was an untried experiment. "It is a very bold experiment," he said; "our colonies are democratic in the highest degree; why do they not try it?" and again, "This is an experiment so large and bold that it ought to be tried by some other country first." Mr. Asquith, in the course of his speech, said much the same thing: "We have no experience to guide us one way or the other." Mr. Goldwin Smith, an extra-Parliamentary opponent of women's suffrage, pointed, in an article, to its solitary example in the State of Wyoming, where it had been adopted in 1869, and asked why, if suffrage had been a success in Wyoming, its example had not been followed by other states immediately abutting on its borders.

Now it has frequently been noticed that when this line of argument is adopted it seems to be a sort of "mascot" for women's suffrage. When Mr. Bryce inquired in 1892 "why our great democratic colonies had not tried women's suffrage," his speech was followed in 1893 by the adoption of women's suffrage in New Zealand and in South Australia. When Mr. Goldwin Smith asked why the States which were in nearest neighbourhood to Wyoming had not followed her example, three States in this position, namely Colorado in 1893, Utah in 1895, and Idaho in 1896, very rapidly did so. When Sir F. S. Powell, in 1907, said in the House of Commons that no country in Europe had ever ventured on the dangerous experiment of enfranchising its women, women's suffrage was granted in Finland the same year, and in Norway the year following. When Mrs. Humphry Ward wrote in 1908 that our cause in the United States was "in process of defeat and extinction," this was followed by the most important suffrage victories ever won in America – the States of Washington in 1910, and California in 1911.

The question arises why so well informed and careful a political controversialist as Mr. James Bryce spoke as he did in 1892 of the fact that none of our great democratic colonies had adopted women's suffrage, in evident ignorance of the fact that two at any rate were on the point of doing so. The answer is probably to be found in the attitude of the anti-suffrage press. No body of political controversialists are so badly served by their own press as the anti-suffragists. The anti-suffrage press appears to act on the assumption that if they say nothing about a political event it is the same as if it had not happened. Therefore, while they give prominence to any circumstances which they imagine likely to be injurious to suffrage, they either say nothing about those facts which indicate its growing force and volume, or record them in such a manner that they escape the observation of the general reader. The result is that only the suffragists, who are in constant communication with their comrades in various parts of the world and also have their own papers, are kept duly informed, not only of what has happened, but of what is likely to happen. Mr. Bryce cannot have known of the imminence of the success of women's suffrage in New Zealand and South Australia in 1892. Mrs. Humphry Ward did not know in February 1909 that women's suffrage had actually been carried in Victoria, and had received the royal assent in 1908. She could have known very little of the real strength of the suffrage movement in the United States, when she said it was virtually dead, just at the moment when it was about to give the most unmistakable proofs of energy and vigour. For all this ignorance the anti-suffrage press of London is mainly responsible. "Things are what they are and their consequences will be what they will be," whether the newspapers print them or not, and to leave the controversialists on your own side in ignorance of facts of capital importance is a strange way of showing political allegiance.[19]

It is a mistake to represent that women's suffrage was brought about in New Zealand suddenly or, as it were, by accident. The women of New Zealand did not, as has sometimes been said, wake up one fine morning in 1893 and find themselves enfranchised. Sustained, self-sacrificing, painstaking, and well-organised work for women's suffrage had been going on in the Colony for many years.[20] The germ of it may be traced even as early as 1843, and many of the most distinguished men whose names are connected with New Zealand history as true empire-builders have been identified with the movement, including Mr. John Ballance, Sir Julius Vogel, Sir R. Stout, Sir John Hall, and Sir George Grey. It is curious that Mr. Richard Seddon, under whose Premiership women's suffrage was finally carried, was not at that time (1893) a believer in it. He was a Thomas who had to see before he could believe, but when he had once had experience of women's suffrage, he was unwearied in proclaiming his confidence in it. When he was in England in 1902 for King Edward's Coronation he hardly ever spoke in public without bearing his testimony to the success of women's suffrage. Much good seed had been sown in New Zealand by Mrs. Müller, an English lady, who landed in Nelson in 1850. One of her articles, signed "Femina" (she was obliged to preserve her anonymity for reasons of domestic tranquillity), won the attention of John Stuart Mill, and drew from him a most encouraging letter, and the gift of his book The Subjection of Women. Mrs. Müller died in 1902, and thus had the opportunity of seeing in operation for nearly ten years the successful operation of the reform for which she had been one of the earliest workers. An American lady, Mrs. Mary Clement Leavitt, visited New Zealand in 1885 on behalf of the Women's Christian Temperance Union. Mrs. Leavitt was a great organiser and arranged the whole of the work of the Temperance Union in definite "Departments," and a general superintendent was appointed to each. There was a Franchise Department, the general superintendent of which was Mrs. Sheppard, who, from 1887, became an indefatigable and, at the same time, a cautious and sensible worker for the extension of the Parliamentary franchise to women. She was in communication with Sir John Hall and other Parliamentary leaders, and kept in close touch with the whole movement until it was successful.

Just as it is now in England with us, differences arose among New Zealand suffragists as to how much suffrage women ought to have, or at any rate for how much would it be wise to ask, and the parties were called the "half loafers" and the "whole loafers." The "no bread" party watched these differences just as they do in England, and tried unsuccessfully to profit by them. In the debate on Sir John Hall's Women's Suffrage resolution in 1890, Mr. W. P. Reeves, so long known in England as the Agent-General for New Zealand, and later as the Director of the London School of Economics, and also as an excellent friend of women's suffrage, announced himself to be a "half loafer"; indeed he advocated the restriction of the franchise to such women, over twenty-one years of age, who had passed the matriculation examination of the university. There is an Arabic proverb to the effect that the world is divided into three classes – "the immovable, the movable, and those who actually move." It is unwise to despair of the conversion of any anti-suffragist unless he has proved himself to belong to the "immovables." In 1890 Mr. Reeves, now so good a suffragist, had only advanced to the point of advocating the enfranchisement of university women. His proposal for a high educational suffrage test for women did not meet with support. It was rejected by more robust suffragists as "not even half a loaf, only a ginger nut." The anti-suffragists used the same arguments which they use with us. They professed themselves to be intimately acquainted with the views of the Almighty on the question of women voting. "It was contrary to the ordinance of God"; women politicians were represented as driving a man from his home because it would be infested "with noisy and declamatory women." After the Bill had passed both Houses a solemn petition was presented by anti-suffragists, who were members of the Legislative Council, asking the Governor to withhold his assent on the ground that "it would seriously affect the rights of property and embarrass the finances of the colony, thereby injuriously affecting the public creditor." Others protested that it was self-evident, that women's suffrage must lead to domestic discord and the neglect of home life. Of course all the anti-suffragists were certain that women did not want the vote, and would not use it even if it were granted to them.

The French gentleman who called himself Max O'Rell was touring New Zealand at the time, and deplored that one of the fairest spots on God's earth was going to be turned into a howling wilderness by women's suffrage. Mr. Goldwin Smith wrote that he gave women's suffrage ten years in New Zealand, and by that time it would have wrought such havoc with the home and domestic life that the best minds in the country would be devising means of getting rid of it. A New Zealand gentleman, named Bakewell, wrote an article in The Nineteenth Century for February 1894, containing a terrible jeremiad about the melancholy results to be expected in the Dominion from women's suffrage. The last words of his article were, "We shall probably for some years to come be a dreadful object lesson to the rest of the British Empire." This was the prophecy. What have the facts been? New Zealand has become an object-lesson – an object-lesson of faithful membership of the Imperial group, a daughter State of which the mother country is intensely proud. Does not everybody know that New Zealand is prosperous and happy and loyal to the throne and race to which she owes her origin.[21] New Zealand was the first British Colony to enfranchise her women, and was also the first British Colony to send her sons to stand side by side with the sons of Great Britain in the battlefields of South Africa; she was also the first British Colony to cable the offer of a battleship to the mother country in the spring of 1909. She, with Australia, was the first part of the British Empire to devise and carry out a truly national system of defence, seeking the advice of the first military expert of the mother country, Lord Kitchener, to help them to do it on efficient lines. The women are demanding that they should do their share in the great national work of defence by undergoing universal ambulance training.[22]

New Zealand and Australia have, since they adopted women's suffrage, inaugurated many important social and economic reforms, among which may be mentioned wages boards – the principle of the minimum wage applied to women as well as to men – and the establishment of children's courts for juvenile offenders. They have also purged their laws of some of the worst of the enactments injurious to women. If it were needed to rebut the preposterous nonsense urged by anti-suffragists against women's suffrage in New Zealand eighteen years ago, it is sufficient to quote the unemotional terms of the cable which appeared from New Zealand in The Times of July 28, 1911: —

"Parliament was opened to-day. Lord Islington, the Governor, in his speech, congratulated the Dominion on its continued prosperity. The increase in the material well-being of the people, was, he said, encouraging, and there was every reason to expect a continuance and even an augmentation of the prosperity of the trade and industry of the Dominion… The results of registration under the universal defence training scheme were satisfactory. The spirit in which this call for patriotism had been met was highly commendable."

The testimony concerning the practical working of women's suffrage in Australia and New Zealand is all of one kind. It may be summarised in a single sentence, "Not one of the evils so confidently predicted of it has actually happened." The effect on home life is universally said to have been good. The birth-rate in New Zealand has steadily increased since 1899, and it has now, next to Australia, the lowest infantile mortality in the world. In South Australia, where women have been enfranchised since 1893, the infantile death-rate has also been reduced from 130 in the 1000 to half that number. Our own anti-suffragists are quite capable of representing that this argument means that we are so foolish as to suppose that if a mother drops a paper into a ballot-box every few years she thereby prolongs the life of her infant. Of course we do nothing of the kind; but we do say that to give full citizenship to women deepens in them the sense of responsibility, and they will be more likely to apply to their duties a quickened intelligence and a higher sense of the importance of the work entrusted to them as women. The free woman makes the best wife and the most careful mother.

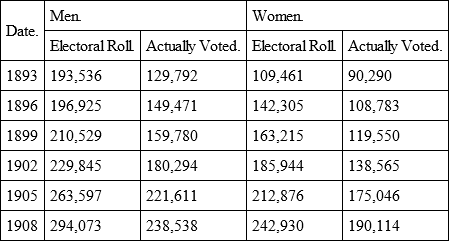

The confident prediction that women when enfranchised would not take the trouble to record their votes has been falsified. The figures given in the official publication, The New Zealand Year Book, are as follows: —

This table shows that men and women who are on the electoral roll vote in almost the same proportion. The number of votes actually polled compared with the number on the register is, of course, to some extent affected by the number of constituencies in which there is no contest, or in which the result is regarded as a foregone conclusion; but this consideration affects both sexes alike. It is impossible for reasons of space to enter in detail in this little book upon the history in each of the Australian States of the adoption of women's suffrage. But it is well known that every one of the States forming the Commonwealth of Australia has now enfranchised its women, and that one of the first acts of the Commonwealth Parliament in 1902 was to grant the suffrage to women. The complete list of dates of women's enfranchisement in New Zealand and Australia will be found in The Brief Review of the Women's Suffrage Movement, which concludes this little book.

When the Premiers and other political leaders from the overseas Dominions of Great Britain were in London for the Coronation and Imperial Conference of 1911, the representatives of Australia and New Zealand frequently expressed both in public and in private their entire satisfaction with the results of women's suffrage. Mr. Fisher, the Premier of the Commonwealth, constantly spoke in this sense: "There is no Australian politician who would nowadays dare to get up at a meeting and declare himself an enemy… It has had most beneficial results… He had not the slightest doubt that women's votes had had a good effect on social legislation… The Federal Parliament took a strong stand upon the remuneration of women, and the minimum wage which was laid down applied equally to women and men for the same work" (Manchester Guardian, June 3, 1911). On another occasion Mr. Fisher said that so far from women's suffrage causing any disunion between men and women, "the interest which men took in women's affairs when women had got the vote was wonderful" (Manchester Guardian, June 10, 1911). Sir William Lyne, Premier of New South Wales, said: "When the women were enfranchised in Australia they proceeded at each election to purify their Parliament, and they had gone on doing so, and now he was proud to say their Parliament was one of the model Parliaments of the world" (Manchester Guardian, August 1, 1911). The Hon. John Murray of Victoria and the Hon. A. A. Kirkpatrick spoke in the same sense. Indeed the evidence favourable to the working of women's suffrage is overwhelming, and is given not only by men who have always supported it, but by those who formerly opposed it, and have had the courage to acknowledge that as the result of experience they have changed their views. Among these may be mentioned Sir Edmund Barton, the first Premier of the Commonwealth, and the late Sir Thomas Bent, the Premier of Victoria, under whose administration women were enfranchised in that State. Why appeal to other witnesses when both Houses of the Commonwealth Parliament in November 1910 unanimously adopted the following resolution: —

"(i.) That this { House Senate} is of opinion that the extension of the Suffrage to the women of Australia for States and Commonwealth Parliaments, on the same terms as men, has had the most beneficial results. It has led to the more orderly conduct of Elections, and at the last Federal Elections the women's vote in the majority of the States showed a greater proportionate increase than that cast by men. It has given a greater prominence to legislation particularly affecting women and children, although the women have not taken up such questions to the exclusion of others of wider significance. In matters of Defence and Imperial concern, they have proved themselves as far-seeing and discriminating as men. Because the reform has brought nothing but good, though disaster was freely prophesied, we respectfully urge that all Nations enjoying Representative Government would be well advised in granting votes to women."

With all this wealth of testimony rebutting from practical experience almost every objection urged against women's suffrage, it is impossible to exaggerate the value to the movement here of the example of Australia and New Zealand. There are few families in the United Kingdom that have not ties of kindred or of friendship with Australasia. The men and women there are of our own race and traditions, starting from the same stock, owning the same allegiance, acknowledging the same laws, speaking the same language, nourished mentally, morally, and spiritually from the same sources. We visit them and they visit us; and when their women return to what they fondly term "home," although they may have been born and brought up under the Southern Cross, they naturally ask why they should be put into a lower political status in Great Britain than in the land of their birth? What have they done to lose one of the most elementary guarantees of liberty and citizenship? As the ties of a sane and healthy Imperialism draw us closer together the difference in the political status of women in Great Britain and her daughter States will become increasingly indefensible and cannot be long maintained.

CHAPTER V

THE ANTI-SUFFRAGISTS

"We enjoy every species of indulgence we can wish for; and as we are content, we pray that others who are not content may meet with no relief." – Burke in House of Commons in 1772 on the Dissenters who petitioned against Dissenters.

The first organised opposition by women to women's suffrage in England dates from 1889, when a number of ladies, led by Mrs. Humphry Ward, Miss Beatrice Potter (now Mrs. Sidney Webb), and Mrs. Creighton appealed in The Nineteenth Century against the proposed extension of the Parliamentary suffrage to women. Looking back now over the years that have passed since this protest was published, the first thing that strikes the reader is that some of the most distinguished ladies who then co-operated with Mrs. Humphry Ward have ceased to be anti-suffragists, and have become suffragists. Mrs. Creighton and Mrs. Webb have joined us; they are not only "movable," but they have moved, and have given their reasons for changing their views. Turning from the list of names to the line of argument adopted against women's suffrage, we find, on the contrary, no change, no development. The ladies who signed The Nineteenth Century protest in 1889 were then as now – and this is the essential characteristic of the anti-suffrage movement – completely in favour of every improvement in the personal, proprietary, and political status of women that had already been gained, but against any further extension of it. The Nineteenth Century ladies were in 1889 quite in favour of women taking part in all local government elections, for women's right to do this had been won in 1870. The protesting ladies said in so many words "we believe the emancipating process has now reached the limits fixed by the physical constitution of women." Less wise than Canute, they appeared to think they could order the tide of human progress to stop and that their command would be obeyed. Then, as now, they protested that the normal experience of women "does not, and never can, provide them with such material to form a sound judgment on great political affairs as men possess," or, as Mrs. Humphry Ward has more recently expressed it, "the political ignorance of women is irreparable and is imposed by nature"; then having proclaimed the inherent incapacity of women to form a sound judgment on important political affairs, they proceed to formulate a judgment on one of the most important issues of practical politics. Several of the ladies who signed The Nineteenth Century protest in 1889 were at that moment taking an active part in organising the political work and influence of women for or against the main political issue of the day, the granting of Home Rule to Ireland; and yet they were saying at the same time that women had not the material to form a sound judgment in politics. This is, of course, the inherent absurdity of the whole position of anti-suffrage women. If women are incapable of forming a sound judgment in grave political issues, why invite them and urge them to express an opinion at all? Besides this fundamental absurdity there is another, secondary to it, but none the less real. Anti-suffragists, especially anti-suffrage men, maintain that to take part in the strife and turmoil of practical politics is in its essence degrading to women, and calculated to sully their refinement and purity. If this, indeed, is so, why invite women into the turmoil? Why advertise, as the anti-suffragists do, the holding of classes to train young women to become anti-suffrage speakers, and thus be able to proclaim on public platforms that "woman's place is home?" This second absurdity appears to have occurred to the late editor of The Nineteenth Century, Sir James Knowles, for a note is added to the 1889 protest apologising, as it were, for the inconsistency of asking women to degrade themselves by taking part in a public political controversy: —