полная версия

полная версияThe Antiquities of Constantinople

Chap. XI.

A Description of Galata; of the Temples of Amphiaraus, Diana, and Venus; of the Theatre of Sycæ, and the Forum of Honorius

THE Sycene Ward, which is commonly called Galata, or Pera, ought more properly to be called the Peræan Ward. Thus it is that Josephus calls Judæa, because it lay on the other Side of the River Jordan: And thus it is, that Strabo calls that Part of the Countrey which lies on the other Side of Euphrates. The Reason alledg’d by the Inhabitants, why ’tis call’d Galata, is, as they tell you, (being impos’d upon by the Allusion of the Name) that Milk was formerly sold there: And I make no Question of it, did they but know, that Galata was formerly call’d Sycæ, they would derive its Name from the Word Fig; and pretend to justify their Mistake from the Authority of Dionysius their Countryman, who says, that it was originally call’d Sycæ, from the Fairness and Abundance of that Fruit which grew there. But their Conjectures had been grounded upon a better Foundation, if they had deriv’d the Name of Galata from the Galatæ, back’d by the Authority of Johannes Tzetzes (a Citizen of Constantinople, and a very industrious Grammarian) in his Var. Hist. written above four hundred Years ago. This Author tells us, that Brenus a Gaul, and Commander in Chief of the Gauls, whom the Greeks call Γαλάται, pass’d over the Sea from thence to a Place of Byzantium, and that this Place for this Reason was call’d Pera, which was after their Arrival call’d Galata. This Place is seated partly on a Hill, and partly on a Plain at the Foot of it. This Hill is enclosed on the East and West by two Valleys, each of which is about a Mile in length. The Ridge of the Hill shoots from North to South, and is in no Part of it less than two hundred Paces broad, and of equal Length with the Valleys that enclose it, and joins to the Plain upon the Continent. The South Side of this Hill, and the Plain below it, is bounded by the Bay of Ceras, which makes it almost a Peninsula of a semicircular Figure, in the Form of a drawn Bow, with this Difference only, that the Western Point of it is larger by half; and not quite so long as the Eastern. Galata, as ’tis enclos’d with a Wall, is four Thousand and four Hundred Paces in Compass. It varies, in many Places, as to its Breadth. In the middle of the Town ’tis six hundred Paces broad. The Bay and the Walls stand at twenty Paces Distance. The Plain that runs between the Bay and the Hill, is a hundred and eighty, and the Hill it self four hundred Paces broad. The Eastern Side of Galata, at the first Entrance of it, is four hundred Paces in breadth; after which it contracts it self into the Breadth of two hundred and sixty Paces only. The Western Side of it, which stands without Old Galata, rises upon a moderate Ascent, which winds Southward, and adjoyns to a small Descent, which terminates Westward near the Walls of Old Galata. The Town therefore of Galata stands upon a Treble Descent; one of which winds from North to South, another falls Easterly, and another at West. The Declivity which crosses the Breadth of it, stretches from North to South; and is so steep, that in many Places you are forced to climb it by Steps; so that you ascend the first Floor of the Houses, which stands upon a Level, by Ladders. The Eastern and Western Side of Galata have a double Declivity; one from North to South, the other to East and West; so that not only those Parts of it which lie in a strait Line, but those Ways also which are winding, or lie Cross-ways, have their Descents; but the Eastern Side of the Town is more upon the Declivity than the Western Side of it. To be short, Galata is of such a Steepness, that if all the Houses were of an equal Height, the upper Rooms would have a full View of the Sea, and of all the Ships sailing up and down in it. And not only Galata, but almost the whole City of Constantinople would have the same Privilege, if that Law, which was first made by Zeno, and afterwards ratify’d by Justinian, was in full Force. This Law expressly forbids any Man to hinder or obstruct an open and entire View of the Sea, or indeed a Side Prospect of it, and enjoyns the Inhabitants to build at least at a hundred Paces Distance from it. The Level Part of the Town, which runs between the Bottom of the Hill and Bay, is, in no Place of it, less than two hundred Paces broad. Towards the Ends of it ’tis much broader; and, in some Places, it widens to the Length of five hundred Paces. The Town is thrice as long as it is broad. It extends it self in Breadth from North to South, in Length from East to West. The Western Side of it is broader than the Eastern, and almost of an equal Breadth with the middle of the City. For in a Length of five hundred Paces, ’tis no less than five hundred Paces broad. The Eastern Side of Galata is more narrow, where it is no more than two hundred and sixty Paces broad. The Shore round the Town is full of Havens. Between the Walls and the Bay is a Piece of Ground, where are Abundance of Taverns, Shops, Victualing-houses, besides several Wharfs, where they unlade their Shipping. It has six Gates, at three of which there are Stairs, from whence you sail over to Constantinople. Galata is so situate to the North of Constantinople, that it faces the first, second, and third Hills, and the first and second Valley of that City; having in Front the Bay of Ceras, and Constantinople, and behind it some Buildings of the Suburbs. For many of these Buildings stand partly on the Top of the Hill, and partly on the Sides of it. The Town, it self does not rise to the Ridge of the Hill. Where Galata rises highest, there is yet standing a very lofty Tower, where there is an Ascent of about three hundred Paces, full of Buildings, and beyond that is the Ridge of the Hill upon a Level, about two hundred Paces broad, and two thousand Paces long. Thro’ the middle of it runs a broad Way full of Houses, Gardens, and Vineyards. This is the most pleasant Part of the Town; from hence, and from the Sides of the Hill, you have a full View of the Bay of Ceras, the Bosporus, the Propontis, the seven Hills of Constantinople, the Countrey of Bithynia, and the Mountain Olympus, always cover’d with Snow. And besides these, there are many other additional Buildings, which adorn the Hills, and Vales adjoining to this Town. It has the same Number of Hills and Vales as Constantinople it self; so that the Inhabitants, whenever they please, can make the Town one third larger than it is at present; and if the Grandeur of the Byzantian Empire continues a hundred Years longer, Galata, it is not improbable, may seem to rival Constantinople it self. They who write that Byzas, the Founder of Byzantium, built the Temple of Amphiaraus in Sycæ, are somewhat in the wrong, tho’ not grosly mistaken. For Dionysius a Byzantian tells us, that behind Sycæ stood the Temple of Amphiaraus, which was built by those who transplanted a Colony to Constantinople, under the Command of Byzas. Both the Grecians, and the Megarians, honour’d Amphiaraus as a God. But altho’ the Temple of Amphiaraus did not stand in the Place which Dionysius calls Sycæ; yet the Word Sycæ signified a larger Tract of Ground, after it was made a City; so that the Temples of Amphiaraus, of Diana Lucifera, and of Venus Placida, all stood within the Limits of it, as I have fully made it appear in my Treatise of the Bosporus. But there are no Remains of these Buildings at present, nor of those Edifices, which, the Antient Description of the City tells you, were in the Sycene Ward. The oldest Man now living cannot so much as tell where those Temples antiently stood, nor ever read or heard, whether there was ever such a Place as the Sycene Ward. Thus far only we can guess from the Rules and Usuage of Architecture, that the Theatre, and Forum of Honorius, stood at the Bottom of the Hill upon a Plain, where Theatres are generally built, as I frequently observ’d in my Travels thro’ Greece. There was standing a Forum, in a Level Ground, (near to the Haven, where is now built a Caravansera, in the Ruines of a Church dedicated to St. Michael) when first I came to Constantinople. This Forum was well supply’d with Water by an ancient subterraneous Aqueduct. In short, there is nothing to be seen at present of old Sycæ. Those antient Pillars we see in some Mosques at Galata, are said to have been imported by the Genoese: Some of them are of very antient Workmanship, and well finish’d. The Cistern of St. Benedict, now despoil’d of its Roof, and three hundred Pillars, which supported it, (now turn’d into a Cistern for watering the Priest’s Gardens) shews it to be a very antique and expensive Work.

From what has been wrote upon this Subject, the Reader may learn how renown’d Constantinople has been for its Monuments of Antiquity. It would take up another Volume, to enlarge upon the Publick Buildings of the Mahometans at present, and to explain for what Uses they were intended. I shall just touch upon a few Things, which are the most remarkable. The City, as it now stands, contains more than three hundred Mosques, the most magnificent of which were built by their Emperors and Basha’s, and are all cover’d at Top with Lead and Marble, adorn’d with Marble Columns, the Plunder and Sacrilege of Christian Churches, as these were before beautify’d with the Spoils of the Heathen Temples. It has above a hundred publick and private Bagnio’s, fifty of which are very spatious, and of two Lengths, much like those I have describ’d, built by their Emperour Mahomet. Their Caravansera’s, and publick Inns, are much above a Hundred; the most famous of which, in the Middle of their Court-yard, are furnish’d with Fountains of Water, brought from the Fields adjoyning to the City. Their Emperors have peculiarly distinguish’d themselves in this Respect. Thus does Eusebius enlarge in the Praise of Constantine: In the middle of their Fora, says he, you may see their Fountains adorn’d with the Emblems of a good Pastor, well known to those who understand the Sacred Writings; namely, the History of Daniel and the Lyons figur’d in Brass, and shining with Plates of Gold. Valens, and Andronicus, at a vast Expence made Rivers, at a remote Distance, tributary to the Town; partly by directing their Courses under Arches, at this Time appearing above Ground, and partly by Channels dug under it. Several other Emperors, with no less Cost, made themselves Fish-ponds, and subterraneous Lakes, by after Ages call’d Cisterns, in every Ward of the City, and that principally to supply them with Water in Case of a Siege. But the Enemies of Constantinople lie at present at such a Distance from them, that they have either entirely ruin’d their Cisterns, or converted them to another Use. I shall take no Notice of the stately Houses of their Noblemen and Basha’s, nor of the Grand Signor’s Palace, which spreading it self all over old Byzantium, is constantly supply’d with Rivers, which flow in upon it, from distant Parts of the Neighbouring Countrey. I pass by their Lakes and Conduits, seated in every Part of the City, which serve them not only with Water to drink, but likewise carry off the Filth of it into the Sea, and wash away those Impurities of the Town, which clog and encumber the Air, and for which great Cities are generally look’d upon as unwholsome. I shall not mention at present, that almost all the Buildings of Constantinople are low, and made out of the Ruines, which the Fire and Earthquakes had spar’d; that many of them are not two Story high, rebuilt with rough Stones, or with burnt, and sometimes unburnt Bricks. I omit also the Houses of Galata, built by the Genoese. The Greeks who profess Christianity, have lost their six hundred Churches, and have not one left, of any Note, except the Church belonging to the Monastery, where their Patriarch dwells. The rest are either entirely ruin’d, or prostituted to the Mahometan Worship. The Francks have about Ten, the Armenians only Seven. The Jews have upwards of Thirty Synagogues, which are scarce sufficient to hold the numerous Congregations of that populous Nation. The Reader will view in a better Light the antient Monuments of Constantinople, when he shall peruse the Antient Description of the Wards of the City, finished before the Time of Justinian, and annex’d at the End of this Book. When this Treatise was first wrote, Constantinople was so fully peopled, that those who inhabited the Fora, and the broad Ways were very straitly pent up; nay, their Buildings were so closely joyn’d to one another, that the Sky, at the Tops of them, was scarce discernible. And as to the Buildings in the Suburbs, they were very thickly crowded together, as far as Selymbria, and the Black Sea; and indeed some Part even of the neighbouring Sea, was cover’d with Houses supported by Props under them. For these, and many other Monuments, was Constantinople antiently renown’d; none of which are remaining at present, except the Porphyry Pillar of Constantine, the Pillar of Arcadius, the Church of St. Sophia, the Hippodrom now in Ruines, and a few Cisterns. No Historian has recorded the Antiquities of Old Byzantium, before it was destroy’d by Severus; altho’ it is reasonable to believe, there were very many of them, especially if it be consider’d, that it long flourish’d in those Times of Heroism, when Art and Ingenuity were in high Estimation, and when Rhodes, no ways preferable to Byzantium, was beautify’d with no less than three thousand Monuments. ’Tis easy to form a Judgment, from the Strength and Proportion of its outside Walls, what beauteous Scenes of Cost, and Workmanship were contain’d within. This we know however for a Certainty, that Darius, Philip of Macedon, and Severus, demolish’d many of their Antiquities, and when they had ravag’d the whole City, that the Byzantians made a noble Stand against the Forces of Severus, with Statues, and other Materials, which were Part of the Ruines of the City. I have already in Part accounted for the Ruines of these Curiosities; I shall at present briefly mention some other Causes which contributed thereto; the Principal of which was the Division of their Emperors amongst themselves; frequent Fires, sometimes accidentally, sometimes designedly occasion’d, not only by their Enemies from abroad, but by their own Factions, and civil Dissensions among themselves; some of which burnt with a constant Flame three or four Days together. These Fires were so raging and terrible, that they did not only consume what was purely combustible, but they wasted the Marble Statues and Images, and Buildings made of the most tough and solid Materials whatsoever; nay, so fierce were they, that they devour’d their own Ruines, and laid the most mountainous Heaps of Rubbish even with the Ground. Nor were the antient Monuments of Old Byzantium demolish’d only by their Enemies, but even by those Emperors who had the greatest Regard and Affection for the City; the Chief of whom was Constantine the Great, who, as Eusebius reports, spoil’d the Temples of the Heathen Gods, laid waste their fine Porches, entirely unroofed them, and took away their Statues of Brass, of Gold and Silver, in which they glory’d for many Ages. And to add to the Infamy, that he expos’d them by way of Mockery and Ridicule, in all the most publick Places of the City. To disgrace them the more, he tells us, that he fill’d it with his own Statues of Brass, exquisitely finish’d; and then concludes, that he was so far incensed against the Heathen Monuments, that he made a Law for the utter Abolishment of them, and the entire Destruction of their Temples. How far Eusebius himself, and other Christian Authors were provoked against them, is plainly discernible in their Writings; namely, that they inveigh’d with the same Severity against the Images of their Gods, as they do at present against our Statues. The Emperors Basilius and Gregorius, were bitterly enrag’d not only against the Images themselves, but against those who wrote too freely in Justification of them. I shall not mention many other Emperors, Successors of Constantine, who were so much exasperated even with the Images of the Christians, that they not only destroy’d them, but proceeded with such Rigour against those who devis’d, or painted, or engrav’d them, that they were entitled the Iconomachi, or Champions that fought against them. I shall say nothing of the Earthquakes, mention’d in History, which happen’d in the Reigns of Zeno, Justinian, Leo Conon, Alexius Comnenus, whereby not only the most considerable Buildings of Constantinople, but almost the whole City with its Walls were demolish’d, so that they could scarce discover its antient Foundation, had it not been for the Bosporus, and Propontis, the eternal Boundaries of Constantinople, which enclose it. I pass by the large Wards of the City, which through the Poverty of the Inhabitants, after frequent Fires, and the Ravage of War, lay a long Time in Ruins, but were at last rebuilt; tho’ the Streets are promiscuously huddled up without Regularity, or Order. These were the Causes, as Livy relates of Old Rome, after it was burnt down, that not only the antient common Shores, but the Aquæducts and Cisterns, formerly running in the open Streets, now have their Courses under private Houses, and the City looks rather like one solid Lump of Building, than divided into Streets and Lanes. I shall not mention how the large Palaces of their Emperors, seated in the middle of the City, nor the Seats of the Nobility enclosing great Tracts of Land, nor how the old Foundations still appearing above Ground, nor the Remains of Buildings, discover’d by the nicest Discernment under it, are almost entirely defac’d. Had I not seen, the Time I liv’d at Constantinople, so many ruinated Churches and Palaces, and their Foundations, since fill’d with Mahometan Buildings, so that I could hardly discover their former Situation, I had not so easily conjectured, what Destruction the Turks had made, since they took the City. And tho’ they are always contriving to beautify it with publick Buildings, yet at present it looks more obscurely in the Day, than it did formerly in the Night; when, as Marcellinus tells us, the Brightness of their Lights, resembling a Meridian Sun-shine, reflected a Lustre from their Houses. The Clearness of the Day now only serves to shew the Meanness and Poverty of their Buildings; so that was Constantine himself alive, who rebuilt and beautify’d it, or others who enlarg’d it, they could not discover the Situation of their antient Structures. The Difficulties I labour’d under in the Search of Antiquity here were very great. I was a Stranger in the Countrey, had very little Assistance from any Inscriptions, none from Coins, none from the People of the Place. They, as having a natural Aversion to any thing that’s valuable in Antiquity, did rather prevent me in my Enquiries, so that I scarce dar’d to take the Dimensions of any Thing, being menac’d, and curs’d if I did, by the Greeks themselves. A Foreigner has no way to allay the Heat and Fury of these People, but by a large Dose of Wine. If you don’t often invite them, and tell them you’ll be as drunk as a Greek, they’ll use you in a very coarse manner. Their whole Conversation is frothy and insipid, as retaining no Custom of the old Byzantians, but a Habit of fuddling. It is not the least, among these Inconveniencies, that I could not have Recourse to so many Authors in describing Constantinople, as a Writer may have in describing Old Rome. They are so fond of Change and Novelty, that any Thing may be called Antique among them, which is beyond the Memory of them, or was transacted in the first Stages of Humane Life. And not only the magnificent Structures of antient Times have been demolish’d by them, but the very Names of them are quite lost, and a more than Scythian Barbarity prevails among them. The Turks are so tenacious of their own Language, that they give a new Name to all Places, which are forc’d to submit to their Power, tho’ it be never so impertinent and improper. They have such an Abhorrence of Greek and Latin, that they look upon both these Tongues to be Sorcery and Witchcraft. All the Assistance I had was my own Observation, the Memory, and Recollection of others, and some Insight into antient History. By these Assistances principally I discovered the Situation of the fourteen Wards of the City. The Inhabitants are daily demolishing, effacing, and utterly destroying the small Remains of Antiquity; so that whosoever shall engage himself in the same Enquiries after me, though they may far exceed me in Industry and Application, yet they will not be able to make any farther Discoveries of the Monuments of the fourteen Wards. But it is not my Intention to prefer my self above other Writers; if I can any way be assistant to future Times, my End is answered. I hope I need make no Apology for recording in History such Monuments as are falling into Ruines; and if my Stay at Constantinople was somewhat longer than I intended, I hope it will not be any Imputation upon me, as it was occasioned by the Death of my Royal Master. It was by his Command that I travelled into Greece, not with any Design of staying long at Constantinople, but to make a Collection of the antient Greek MSS. Not with any Intention of describing only that City; but as a farther Improvement of Human Knowledge, that I might delineate the Situation of several other Places and Cities. Upon the Death of my King, (not having Remittances sufficient) I was forc’d, with a small Competency, to travel thro’ Asia, and Greece, to this Purpose; and I can assure the Reader, that I did not undertake this Voyage upon any Prospect of sensual Pleasure, any View of worldly Interest, or any Affectation of popular Applause; no, I could have liv’d in Ease, more to my own Advantage; and in a much better State of Health, as to all Appearance, in my own Countrey. Not all the Dangers and Inconveniencies of a long and a laborious Voyage could ever move me to a speedy Return. How I came to engage my self in such unfortunate Travels I know not. I was very apprehensive of the Troubles and Dangers, which I must necessarily undergo, and which indeed have befallen me, before I ventur’d upon such an Undertaking; yet I would willingly persuade my self, that my Resolutions herein were Good, and my Design Honourable; being confirm’d in the Opinion of the Platonists, That we ought to be indefatigable in the Search of Truth; and, That ’tis beneath a Man to give over, when his Enquiries are Useful, and Becoming.

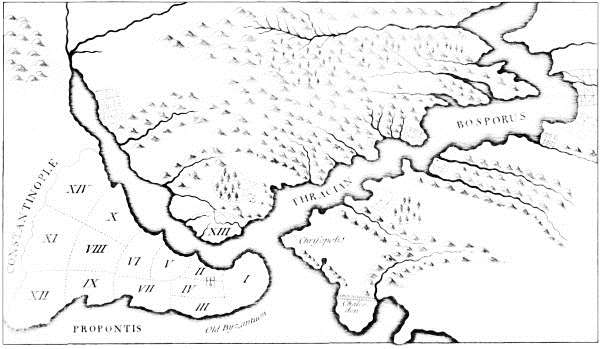

The Thracian Bosporus with Constantinople divided into Wards.

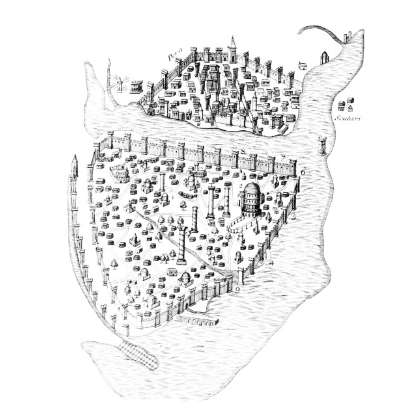

Constantinopolis