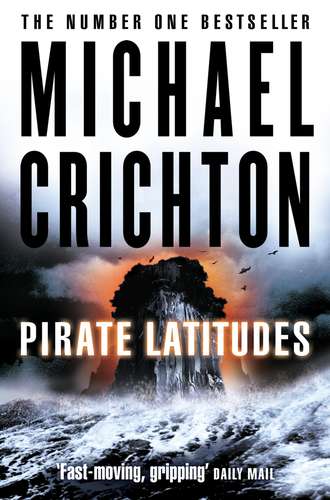

Pirate Latitudes

Полная версия

Pirate Latitudes

Жанр: приключениязарубежные приключениякниги о войнеисторическая литературасовременная зарубежная литературакниги о приключенияхсерьезное чтениеоб истории серьезно

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2018

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу