полная версия

полная версияPerseverance Island

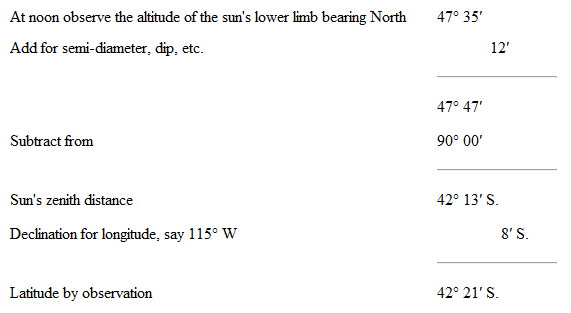

Thus I demonstrated the latitude of my island; but now for the longitude. To obtain that I knew that I must first ascertain the time at the island: I could do nothing without that; for longitude was, as I well knew, simply time changed into degrees. I thought of fifty different ways to obtain correct time, but believed none of them sufficiently accurate for my purpose. I could make a sundial for one thing, find out the length of the day by the Epitome and Nautical Almanac, make candles to burn such a length of time, sand to run down an inclined plane at such a rate, but none of these would do.

The difference of a minute, or one-sixtieth of a degree, in an observed altitude would only affect, as I have said, my latitude just one mile, whilst an error of time of one minute from true time would, as I was well aware, throw my longitude out just fifteen miles; hence it behoved me to have exact time if I desired to get exact longitude, and therefore I saw nothing for it but that I must construct a clock, and at it I went. It was not such an enormous undertaking after all. Of course I should make it of wood, and in my boyhood I knew many wooden clocks that kept excellent time; besides, if I could only construct something that would keep time for an hour or two without much error, it would answer my purpose. If I had a clock that I could set at noon by my observation, nearly correct, I could correct it perfectly by an afternoon observation, and have for an hour or so true time, even if it did gain or lose a few minutes in twenty-four hours. So to work I set, and soon turned out the few small wheels necessary, and the weight and pendulum for the same. I spent little time upon the non-essentials, but put it together inside my house on the wall, open so that I could get at it, and furnished it with wooden hands and a thin wooden face.

After I had arranged it and found that it would tick, and by observations at noon for a few days been able to regulate the pendulum, I went diving into the Epitome and the Nautical Almanac as to how I should utilize it so as to get my longitude, after all; when one evening, in turning over the Nautical Almanac, which was calculated for 1866, 1867, 1868, and 1869, my eye fell upon the following, and I felt that my task was done: —

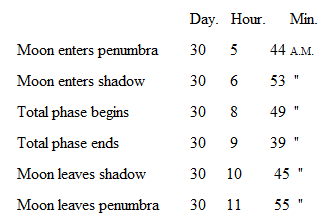

Total eclipse of the moon, September 30,1866, invisible at Greenwich, visible in South America, South Pacific Ocean, and parts of Africa, Asia, and Indian Ocean.

FORMULA (CIVIL ACCOUNT).

This was all I needed to verify my longitude past peradventure, and I went to work at once, calculating when the eclipse ought to take place, nearly, with me.

At a rough calculation I knew that my island was situated somewhere between the 110° and 120° of longitude west of Greenwich, that is to say, in the neighborhood of seven hours' difference of time later than Greenwich time. Therefore I knew that if the moon entered the penumbra at Greenwich (although invisible) on the 30d. 5h. 44 min. A.M. that I ought to look for it to occur visibly to my eyes somewhere from one to two o'clock in the afternoon of the same day, or seven hours later. The exact difference in the time between Greenwich and that to be observed on my island, changed into degrees and minutes, would, of course be the true longitude west of Greenwich.

It was with the utmost anxiety that I awaited the coming of the 30th of September, for it all depended upon pleasant weather whether or not I should be able to make my observation. I placed my astrolabe so as to be able to move it quickly in any needed direction, as I intended to use the tube to look at the sun through so as not to blind my eyes. I also prepared my birch bark in the house, and commenced practising myself in counting seconds, for I should have to leave my instrument and go to the house, counting all the time to note the time marked by my clock. I found upon practice that I could not make this work very successfully, and that according to the state of my feelings or excitement I counted long and short minutes. This would not do; I must invent something better; and I finally bethought myself of counting the beatings of my pulse with the finger of one hand upon the wrist of the other, and applying the proportion to the interval between the observed time by my clock.

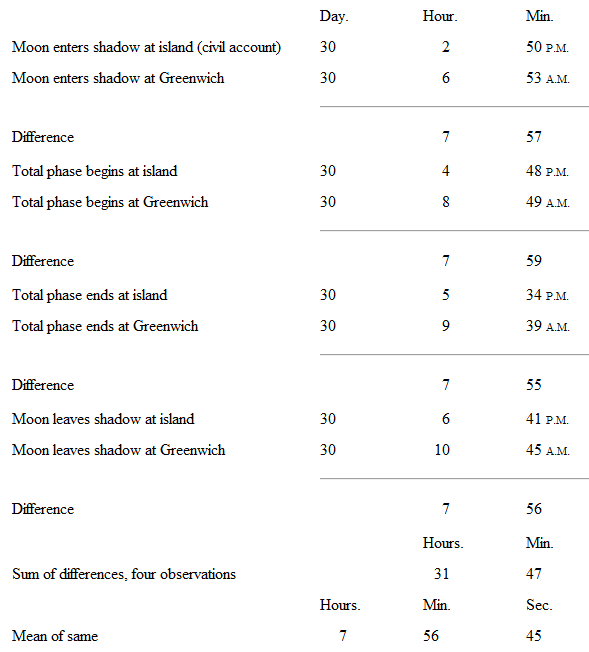

The morning at last came that I so much desired, and nothing could be more beautiful than the balmy, spring-like day that surrounded me. The sky was cloudless and the sun shone down in splendor through a clear and pure atmosphere. The morning passed slowly away, and it seemed as if the moon and sun would never approach each other; but finally, in the afternoon, the heavens showed me that the eclipse would soon take place, and I made my arrangements to take four observations, as follows: Time when moon entered shadow; time when total phase began; time when total phase ended; time when moon left shadow.

Nothing could have been better than the afternoon I experienced to make these observations, and in less than six hours the whole affair was over, with the following result, I having carefully regulated my clock as near as possible by an observation at noon: —

Which, reduced to time, gives the longitude of the island 119° 11′ 15″ west of Greenwich.

There, my problem was done and I was for the moment happy. Perhaps some will wonder why I cared to obtain the latitude and longitude of my island at all. Let me explain. My Bowditch's Epitome gave the latitude and longitude of all prominent capes, harbors, headlands, light-houses, etc., in the whole Pacific Ocean. In other words, knowing now the latitude and longitude of my own island, I had only to project a chart on Mercator's projection, pricking off the relative positions of the land on all sides of me, as well as the position of my island, to have a practical and useful chart. Of course I should not be able to draw the coast line or the circumference of any island, but my chart would show just what latitude and longitude Easter Island was in, for instance, and just how far and in exactly what direction my island lay from it. Also, how far I was from the American coast, and the exact distance and course from any of the principal ports such as Lima, Valparaiso, Pisco, etc. How far from New Zealand and the Society Islands, and in what direction from them.

Having marked the exact latitude and longitude of each of these places, which were fully given in the Epitome, on my chart, I could call upon my memory often to fill in the coast lines, and even if I should in the case of the islands, make them even imaginary, there would be no harm done, for the little black star on each would show me where the latitude and longitude met exactly, and I should be furnished with a practical chart as far as sea navigation was concerned, but not one that would be of much account in entering any harbors.

I cannot say that at this time I had any fixed plan of escaping from the island, but I very well knew that nothing in the world would aid me so much in the attempt as to know the position in latitude and longitude that the island occupied, and a chart of the surrounding seas, with its numerous islands and headlands on the main land. It can well be conceived that my first task after determining the position of my island was to turn to the Epitome to ascertain the nearest land to me there marked down, and after diligent search this is what I found: —

"Easter Island Peak," 27° 8′ south latitude and 109° 17′ west longitude.

"Island," 28° 6′ south latitude and 95° 12′ west longitude.

"Group of Islands," 31° 3′ south latitude and 129° 24′ west longitude.

"Massafuera," 33° 45′ south latitude and 80° 47′ west longitude, which I speedily worked out, by the principles of Mercator's sailing, to be in course and distance from my island, as follows: —

Of these four places only two ever had a name, and I did not know whether Easter Island was inhabited or not, and about Massafuera I was totally ignorant.

Easter Island, I knew, of course, was one of the so-called Society Islands, and was the nearest practical land to which I could escape. But how was I safely to pass over a thousand miles of water? This investigation only proved to me what I had so long feared, namely, that my island was out of the track of all trade, and that it would be a miracle should I be preserved by the arrival of any vessel. I knew now that I must really give up all hope in that direction, and set to work seriously to help myself.

I therefore applied myself with great vigor to my chart which I outlined upon nice goatskin parchment, which I glued together till I had a surface nearly four feet square, upon which I could lay out all the Pacific Ocean on a nice, large scale, by Mercator's projection. I went on with my daily work, and made this matter one for evening amusement, and as I pricked off the latitude and longitude of some well-known place, that I in former years had visited, my heart swelled within me with grief and mortification, and I had often to stop and wipe the tears from my eyes before I could proceed.

Release from my prison seemed farther from me than ever, as I advanced in my task, and although I had a sort of morbid pleasure in my work, and a fascination to linger over it, yet I saw plainly that I was indeed cast away; for what could I do alone in a boat, even supposing that I could build one strong enough to resist one thousand miles of water? Who was to steer when I was asleep? and then supposing I should be able to arrive at Easter Island, what guarantee had I that I should not be murdered at once by the natives?

No, here I was fixed beyond fate upon my own island, where, with the exception of companionship, I had everything that human heart could wish for. But on the other hand, without companionship I lacked everything that is worth living for in this world. I felt that the problem of all problems hereafter to me would be how can I escape to some civilized country in safety? And from what I now knew, it seemed as if it would remain a problem till my bones were left whitening in the Hermitage.

My discovery of the latitude and longitude of the island had brought me no comfort, and I felt much more uneasy now than I did before finishing my task. But as the summer weather came on, I regained to a degree my good spirits, keeping, however, the problem of escape continually working in my mind, for I knew that there must be some way to solve it, especially with the resources that I had gathered around about me.

CHAPTER XVIII

A resumé of three years on the island. Daily routine of life. Inventions, discoveries, etc. Fortification of the Hermitage. Manufacture of cannon and guns. Perfection and improvement of the machine shop. Implicit faith of ultimately overcoming all obstacles and escaping from the island. Desire to accumulate some kind of portable wealth to carry with me, and decide to explore the island for its hidden wealth and the surrounding ocean for pearl oysters.

I shall not become tedious by inflicting upon my readers the routine of each day, or even of each month or year that I have passed on this island, but shall pick out the most startling events of my life here, both as to the inventions that I have made and the accidents and adventures of which I have been the victim and hero.

Of course my discovery of iron gave me wonderful power to advance and preserve myself. After my first set of tools were made, as I have enumerated in detail, all other work, even if slow, was comparatively easy.

My next task, after making the common tools that I needed and various castings that were useful to me, was to erect a turning lathe, – one for wood, which was quite simple, and one for iron, which was a work of some magnitude, – and a whole year elapsed before I had it perfected to my taste. The castings were rough, but solid and useful, and the other parts were, with care and attention, at last made mathematically true, and this, with a drilling machine and some iron rollers to roll out my metal when coming from the furnace, completed my iron foundry, as I was now pleased to call it.

Having all these things about me it was a small matter to cast several small cannon, of some four or six pound calibre, and bore them out on my turning-lathe and table. These I mounted on wooden trucks, and placed one on East Signal Point, one on Eastern Cape, one on South Cape, which I transported there by water in the canoe Fairy, one on Penguin Point, and one on West Signal Point. It was fun for me to make these things, and therefore, to protect myself still more, I made a number, of smaller calibre even, which I placed pointing out through embrasures in a wall with which I had encircled the Hermitage, and surrounded with a strong picket fence, made of cast-iron, which I found no difficulty in casting in sections of nearly ten feet in length. At all the stations at the extremities of the island I hid a little amount of ammunition, near the cannon erected, and also a flint and steel and a limestock or slow-match, so that at any time, if needful, I could load one of these cannon at once and discharge it. The touchholes I covered nicely with a piece of goatskin, so as to protect the guns from the weather, and fitted all the muzzles with a wooden plug, so that the interior would be kept clear and dry.

In the wall that now surrounded my Hermitage I built a strong iron gate, that I could see through and yet too strong to be broken down by any savage hands. The iron fence or comb which ran round the summit of this wall, and of which I have spoken, crossed also above the gateway, and made my house impregnable to anything except artillery. My doorway facing this, in the Hermitage itself, had long been replaced by a nice hard-wood one, with iron hinges, with several loopholes left, through which I could poke a gun-barrel or discharge an arrow.

I had six cannon mounted on my wall, two in front, two on each side, and one in rear, which was, however, naturally protected by a thick and almost impenetrable grove of trees and undergrowth. These guns were mounted in a peculiar manner upon carriages that allowed the muzzles to be depressed at least thirty degrees, and I kept in store, to load them with, quantities of iron ball castings, from the size of an English walnut to a common musket bullet, which at close quarters would do fearful execution. I approached these guns, from the interior, by means of step ladders, made of wood, leading up to each from the enclosure, and an oval hole, like an inverted letter U, was left in the iron fencing to allow the muzzle to protrude over the wall. This opening, however, was small, and not large enough to admit even the head of a man, much less his body. The erection of the whole wall, which was some nine feet high, cost me infinite labor and patience.

The fencing on top of it was, as I have said, rapidly turned out from the casting mould, and gave me, comparatively speaking, little trouble. To further protect this my fortress from any assaults, I brought the water underground from Rapid River into the Hermitage, through a series of pipes made of pottery thoroughly baked, glazed, and made so as to fit one into the other, and controlled the flow by means of a stopcock fixed into a piece of cane. The signs of this underground connection with Rapid River I took care to thoroughly efface. And, furthermore, I made it a duty to always keep at least six months' salted provisions in store, ahead of all demands, – such as salted and smoked herring, salmon, and other fish, with corned and dried goat's flesh, and some few preserved vegetables such as I might have on hand.

In rear of my house, between the end of the house and the wall, I dug a subterranean passage, leading under my wall, and coming again to the surface in the midst of a seemingly impenetrable thicket of undergrowth, some thirty yards away from the wall. This outlet was carefully closed by a trapdoor, and soil even strewed on top and grass allowed to grow over it. I did not know but what there might come a time when I should have to use this passage, as the last recourse, to save my life; and although now in security I built it carefully, to be prepared for what might happen in the future.

After all these tasks for my defence were finished I commenced upon a set of guns and pistols, or rather rifles, – for I had not the slightest use for a shotgun, being able, in a hundred ways, by means of steel-traps and similar devices, to capture all the birds and animals I needed, – which I desired to protect myself against any human enemies, should such ever appear. To this end I easily bored myself out some four nice rifle barrels, and some half dozen of a smaller size for pistols; these I had to stock, and mount with the old-fashioned flint and steel, for I had no means of making any percussion-powder. I worked at these for a long time, but at last I had them all in good order, and used to amuse myself by practising with ball at the pigeons on the trees, and the ducks on the river. I did not make the best shooting in the world, for, not being able to procure lead, I was forced to make my bullets of steel, and to revolve them in a cylinder for a long time with sand, to make them globular and regular. The barrels of my guns and pistols also had to be smooth bored to use these projectiles; as a rifled barrel, if I could have made one, would have been ruined by cast-steel bullets; still at a hundred yards, with a nice greased patch, I was able to make good execution, and the pistols shot with strength at a distance of at least twenty yards. Both weapons suited me practically, and with my guns I had no difficulty in shooting several of the wild goats, and also seals, whenever I needed their meat or skins.

My flock of tame goats all this while had grown and increased, and I added to my home comforts cheese and butter; but I made the wheel on the further side of the river do all the churning by a simple application of the machinery to a revolving clapper in an upright churn.

The parchment windows in the Hermitage had long since been reinforced by iron shutters on the outside, that, if needed, could be bolted securely on the inside, and the roof had been refitted and made of timber and boards, and the whole covered with tiles, so as to be fireproof. Up through this roof I had also built a tower, of brick, not very large but quite high, some feet above the ridge-pole, which I mounted to by a flight of stairs from the attic; for the upper part of the house was floored off and completed when I erected the new roof, having no want now of either boards or timber.

Up to this tower I trotted every morning before unbarring the door of the Hermitage or the gate of the enclosure. From this lookout I could see quite well in several directions, and notice if anything had been touched or changed from the evening before. I missed, I think, at this time, books more than anything, but then, again, from the very want of them, I was forced to study with my Epitome and Book of Useful Arts and Sciences, which possibly I might have thrown to one side for less useful but more entertaining ones if I had had them. Wanting them, I was becoming versed in many things which when I came upon the island I knew nothing about, and I was pleased to think that, although alone, I was improving, and the usefulness of a really good book was brought forcibly before me each day, for I could not open either of mine without finding food for reflection and study. I had always had my head full of vagaries of different kinds that I should like some time to try and experiment upon, and here seemed my opportunity; and it will be observed, in its proper place, further on, that I attempted many things.

It was, I think, in my third year that I felt that my daily routine was fixed for life, as far as concerned comforts and food; for by that time I had wheat for my bread, and all kinds of vegetables and fruits that I have before enumerated, in profusion. My apple and pear trees would soon begin to bear, and in a year or two more I should have them to add to my comforts. I had already commenced to preserve blackberries, strawberries, etc., and found that my maple trees, in the spring, were just as prolific as those in my Vermont home, and that I had no difficulty in obtaining all the sugar I needed. Roasted wheat had, however, to stand me instead of Java coffee, but this made me quite a pleasant drink.

All these comforts were enhanced by a climate so uniform in temperature that it was a pleasure to even exist, the winters bringing scarcely an inch of snow or ice with them, and the summers even and mild; warm, to be sure, but still far from being hot or oppressive. As I have said so often in this narrative before, what in the world could one want in excess of all this but companionship? Ah! it is little known how many bitter hours of solitude I passed in gathering all these comforts about me, and how, with a tenderness almost womanly, I made friends with every kid, duck, young bird, seal, and living animal that I gathered around me, and made pets of them all. My hardest duties were to destroy these animals for my own consumption, and I latterly destroyed what I could with the gun rather than touch one of those that were domesticated. Some of these I could not bear to lay my hand upon, especially my young kids and team of goats; but thank God there was no need of it. I could easily destroy one of their species, when I needed the flesh, with my rifle, for I veritably believe that I should have gone without animal food rather than touch one of these pets. Two of the kids, especially, followed me about all the time, and even into my canoe when I took short trips abroad.

I had by this time, by means of snares, captured seven species of birds which resembled our blackbirds and bobolinks of the north, and I took great delight in feeding them in the cages I had made for them, and listening to their music in the morning and evening hours. Long search had taught me to feel sure that the island had no venomous insects or reptiles, and it was also wholly free from that nuisance the horse-fly, which is said to follow civilization, and that other pest, the mosquito, was wholly unknown. In their stead there were a few sand-fleas, a sort of wood-tick, which troubled the goats somewhat, and a small black wood-fly, that was not troublesome except in some seasons, in the woods, and on the coast. In December and January, green-headed flies were apt to take hold of me once in a while, but not so as to incommode me.

The air was so pure that meat would keep a long while without putrefaction, even in the warm weather, and having nothing better to do to take up my mind, I had, during the past winter, collected quite an amount of thin ice from Rapid River, which, in a small subterranean ice-house, roofed over with planks, and covered with sawdust, I had stored for summer use, and on very warm days luxuriated in.

This life of solitude had made me tender to even inanimate things, and it was wonderful to myself how the passion, self-importance, and arbitrary manner of one accustomed to command at sea was dying out in me. I began to almost have a reverence for flowers and all beautiful inanimate things, and many hours of my life were passed in my garden and on my farm, but especially the former, in examining and cultivating some beautiful wild flower or trailing vine that I had transported hence from the forest. I felt even that the bearing of my body was changed from what it used to be when in days gone by I trod the quarter-deck in all the pride and majesty of power.

I cannot say that I was at this time contented, but I can say that I was much more patient, and the impetuosity of my temperament was greatly subdued, and many things, both animate and inanimate, were becoming, in spite of myself, very dear to my eyes. I even at times began to feel homesick when I was absent over a day, in my canoe, from the Hermitage, and came back to its comforts with an exclamation of gratification and a swelling of the heart with joy when it came in view, and showed itself intact during my temporary absence; and the welcome given me by my goats, tame pigeons, ducks, and birds was very touching, and, as I have said, endeared them to me greatly. Still for no moment did the problem of escape leave my mind. Although without relatives or children, I often dreamed of escaping from the island and returning with friends to enjoy it with me and end my days here in peace. I often thought how happy I could be here, far from the cares of the world and all its vain excitements, could I see around about me smiling faces of my fellow-men, who would look up to me as their benefactor and ruler, for I had yet left some of the seaman's instinct of desire to rule.