полная версия

полная версияA General Introduction to Psychoanalysis

The difference of these two destinies, arising from the same experience, is due to the fact that one ego has experienced development while the other has not. The janitor's daughter in later years looks upon sexual intercourse as the same natural and harmless thing it had seemed in her childhood. The owner's daughter had experienced the influence of education and had recognized its claims. Thus stimulated, her ego had forged its ideals of womanly purity and lack of desire which, however, could not agree with any sexual activity; her intellectual development had made unworthy her interest in the woman's part she was to play. This higher moral and intellectual evolution of her ego was in conflict with the claims of her sexuality.

I should like to consider today one more point in the development of the ego, partly because it opens wide vistas, partly because it will justify the sharp, perhaps unnatural line of division we are wont to draw between sexual and ego impulses. In estimating the several developments of ego and of libido, we must emphasize an aspect which has not frequently been appreciated heretofore. Both the ego and the libido are fundamentally heritages, abbreviated repetitions of an evolution which mankind has, in the course of long periods of time, traversed from primeval ages. The libido shows its phylogenetic origin most readily, I should say. Recall, if you please, that in one class of animals the genital apparatus is closely connected with the mouth, that in another it cannot be separated from the excretory apparatus, and in others it is attached to organs of locomotion. Of all these things you will find a most fascinating description in the valuable book of W. Bölsche. Animals portray, so to speak, all kinds of perversions which have become set as their permanent sexual organizations. In man this phylogenetic aspect is partly clouded by the circumstance that these activities, although fundamentally inherited, are achieved anew in individual development, presumably because the same conditions still prevail and still continue to exert their influence on each personality. I should say that originally they served to call forth an activity, where they now serve only as a stimulus for recollection. There is no doubt that in addition the course of development in each individual, which has been innately determined, may be disturbed or altered from without by recent influences. That power which has forced this development upon mankind, and which today maintains the identical pressure, is indeed known to us: it is the same self-denial enforced by the realities – or, given its big and actual name, Necessity, the struggle for existence, the ’Ανἁγχη. This has been a severe teacher, but under him we have become potent. The neurotics are those children upon whom this severity has had a bad effect – but there is risk in all education. This appreciation of the struggle of life as the moving force of development need not prejudice us against the importance of "innate tendencies in evolution" if their existence can be proved.

It is worth noting that sexual instincts and instincts of self-preservation do not behave similarly when they are confronted with the necessities of actuality. It is easier to educate the instincts of self-preservation and everything that is connected with them; they speedily learn to adapt themselves to necessity and to arrange their development in accordance with the mandates of fact. That is easy to understand, for they cannot procure the objects they require in any other way; without these objects the individual must perish. The sex instincts are more difficult to educate because at the outset they do not suffer from the need of an object. As they are related almost parasitically to the other functions of the body and gratify themselves auto-erotically by way of their own body, they are at first withdrawn from the educational influence of real necessity. In most people, they maintain themselves in some way or other during the entire course of life as those characteristics of obstinacy and inaccessibility to influence which are generally collectively called unreasonableness. The education of youth generally comes to an end when the sexual demands are aroused to their full strength. Educators know this and act accordingly; but perhaps the results of psychoanalysis will influence them to transfer the greatest emphasis to the education of the early years, of childhood, beginning with the suckling. The little human being is frequently a finished product in his fourth or fifth year, and only reveals gradually in later years what has long been ready within him.

To appreciate the full significance of the aforementioned difference between the two groups of instincts, we must digress considerably and introduce a consideration which we must needs call economic. Thereby we enter upon one of the most important but unfortunately one of the most obscure domains of psychoanalysis. We ask ourselves whether a fundamental purpose is recognizable in the workings of our psychological apparatus, and answer immediately that this purpose is the pursuit of pleasurable excitement. It seems as if our entire psychological activity were directed toward gaining pleasurable stimulation, toward avoiding painful ones; that it is regulated automatically by the principle of pleasure. Now we should like to know, above all, what conditions cause the creation of pleasure and pain, but here we fall short. We may only venture to say that pleasurable excitation in some way involves lessening, lowering or obliterating the amount of stimuli present in the psychic apparatus. This amount, on the other hand, is increased by pain. Examination of the most intense pleasurable excitement accessible to man, the pleasure which accompanies the performance of the sexual act, leaves small doubt on this point. Since such processes of pleasure are concerned with the destinies of quantities of psychic excitation or energy, we call considerations of this sort economic. It thus appears that we can describe the tasks and performances of the psychic apparatus in different and more generalized terms than by the emphasis of the pursuit of pleasure. We may say that the psychic apparatus serves the purpose of mastering and bringing to rest the mass of stimuli and the stimulating forces which approach it. The sexual instincts obviously show their aim of pleasurable excitement from the beginning to the end of their development; they retain this original function without much change. The ego instincts strive at first for the same thing. But through the influence of their teacher, necessity, the ego instincts soon learn to adduce some qualification to the principle of pleasure. The task of avoiding pain becomes an objective almost comparable to the gain of pleasure; the ego learns that its direct gratification is unavoidably withheld, the gain of pleasurable excitement postponed, that always a certain amount of pain must be borne and certain sources of pleasure entirely relinquished. This educated ego has become "reasonable." It is no longer controlled by the principle of pleasure, but by the principle of fact, which at bottom also aims at pleasure, but pleasure which is postponed and lessened by considerations of fact.

The transition from the pleasure principle to that of fact is the most important advance in the development of the ego. We already know that the sexual instincts pass through this stage unwillingly and late. We shall presently learn the consequence to man of the fact that his sexuality admits of such a loose relation to the external realities of his life. Yet one more observation belongs here. Since the ego of man has, like the libido, its history of evolution, you will not be surprised to hear that there are "ego-regressions," and you will want to know what role this return of the ego to former phases of development plays in neurotic disease.

TWENTY-THIRD LECTURE

GENERAL THEORY OF THE NEUROSES

The Development of the SymptomsIN the layman's eyes the symptom shows the nature of the disease, and cure means removal of symptoms. The physician, however, finds it important to distinguish the symptoms from the disease and recognizes that doing away with the symptoms is not necessarily curing the disease. Of course, the only tangible thing left over after the removal of the symptoms is the capacity to build new symptoms. Accordingly, for the time being, let us accept the layman's viewpoint and consider the understanding of the symptoms as equivalent to the understanding of the sickness.

The symptoms, – of course, we are dealing here with psychic (or psychogenic) symptoms, and psychic illness – are acts which are detrimental to life as a whole, or which are at least useless; frequently they are obnoxious to the individual who performs them and are accompanied by distaste and suffering. The principal injury lies in the psychic exertion which they cost, and in the further exertion needed to combat them. The price these efforts exact may, when there is an extensive development of the symptoms, bring about an extraordinary impoverishment of the personality of the patient with respect to his available psychic energy, and consequently cripple him in all the important tasks of life. Since such an outcome is dependent on the amount of energy so utilized, you will readily understand that "being sick" is essentially a practical concept. But if you take a theoretical standpoint and disregard these quantitative relations, you can readily say that we are all sick, or rather neurotic, since the conditions favorable to the development of symptoms are demonstrable also among normal persons.

As to the neurotic symptoms, we already know that they are the result of a conflict aroused by a new form of gratifying the libido. The two forces that have contended against each other meet once more in the symptom; they become reconciled through the compromise of a symptom development. That is why the symptom is capable of such resistance; it is sustained from both sides. We also know that one of the two partners to the conflict is the unsatisfied libido, frustrated by reality, which must now seek other means for its satisfaction. If reality remains inflexible even where the libido is prepared to take another object in place of the one denied it, the libido will then finally be compelled to resort to regression and to seek gratification in one of the earlier stages in its organizations already out-lived, or by means of one of the objects given up in the past. Along the path of regression the libido is enticed by fixations which it has left behind at these stages in its development.

Here the development toward perversion branches off sharply from that of the neuroses. If the regressions do not awaken the resistance of the ego, then a neurosis does not follow and the libido arrives at some actual, even if abnormal, satisfaction. The ego, however, controls not alone consciousness, but also the approaches to motor innervation, and hence the realization of psychic impulses. If the ego then does not approve this regression, the conflict takes place. The libido is locked out, as it were, and must seek refuge in some place where it can find an outlet for its fund of energy, in accordance with the controlling demands for pleasurable gratification. It must withdraw from the ego. Such an evasion is offered by the fixations established in the course of its evolution and now traversed regressively, against which the ego had, at the time, protected itself by suppressions. The libido, streaming back, occupies these suppressed positions and thus withdraws from before the ego and its laws. At the same time, however, it throws off all the influences acquired under its tutelage. The libido could be guided so long as there was a possibility of its being satisfied; under the double pressure of external and internal denial it becomes unruly and harks back to former and more happy times. Such is its character, fundamentally unchangeable. The ideas which the libido now takes over in order to hold its energy belong to the system of the unconscious, and are therefore subject to its peculiar processes, especially elaboration and displacement. Conditions are set up here which are entirely comparable to those of dream formation. Just as the latent dream, the fulfillment of a wish-phantasy, is first built up in the unconsciousness, but must then pass through conscious processes before, censored and approved, it can enter into the compromise construction of the manifest dream, so the ideas representing the libido in the unconscious must still contend against the power of the fore-conscious ego. The opposition that has arisen against it in the ego follows it down by a "counter-siege" and forces it to choose such an expression as will serve at the same time to express itself. Thus, then, the symptom comes into being as a much distorted offshoot from the unconscious libidinous wish-fulfillment, an artificially selected ambiguity – with two entirely contradictory meanings. In this last point alone do we realize a difference between dream and symptom development, for the only fore-conscious purpose in dream formation is the maintenance of sleep, the exclusion from consciousness of anything which may disturb sleep; but it does not necessarily oppose the unconscious wish impulse with an insistent "No." Quite the contrary; the purpose of the dream may be more tolerant, because the situation of the sleeper is a less dangerous one. The exit to reality is closed only through the condition of sleep.

You see, this evasion which the libido finds under the conditions of the conflict is possible only by virtue of the existing fixations. When these fixations are taken in hand by the regression, the suppression is side-tracked and the libido, which must maintain itself under the conditions of the compromise, is led off or gratified. By means of such a detour by way of the unconscious and the old fixations, the libido has at last succeeded in breaking its way through to some sort of gratification, however extraordinarily limited this may seem and however unrecognizable any longer as a genuine satisfaction. Now allow me to add two further remarks concerning this final result. In the first place, I should like you to take note of the intimate connection between the libido and the unconscious on the one hand, and on the other of the ego, consciousness, and reality. The connection that is evidenced here, however, does not indicate that originally they in any way belong together. I should like you to bear continually in mind that everything I have said here, and all that will follow, pertains only to the symptom development of hysterical neurosis.

Where, now, can the libido find the fixations which it must have in order to force its way through the suppressions? In the activities and experiences of infantile sexuality, in its abandoned component-impulses, its childish objects which have been given up. The libido again returns to them. The significance of this period of childhood is a double one; on the one hand, the instinctive tendencies which were congenital in the child first showed themselves at this time; secondly, at the same time, environmental influences and chance experiences were first awakening his other instincts. I believe our right to establish this bipartite division cannot be questioned. The assertion that the innate disposition plays a part is hardly open to criticism, but analytic experience actually makes it necessary for us to assume that purely accidental experiences of childhood are capable of leaving fixations of the libido. I do not see any theoretical difficulties here. Congenital tendencies undoubtedly represent the after-effects of the experiences of an earlier ancestry; they must also have once been acquired; without such acquired characters there could be no heredity. And is it conceivable that the inheritance of such acquired characters comes to a standstill in the very generation that we have under observation? The significance of infantile experience, however, should not, as is so often done, be completely ignored as compared with ancestral experiences or those of our adult years; on the contrary, they should meet with an especial appreciation. They have such important results because they occur in the period of uncompleted development, and because of this very fact are in a position to cause a traumatic effect. The researches on the mechanics of development by Roux and others have shown us that a needle prick into an embryonic cell mass which is undergoing division results in most serious developmental disturbances. The same injury to a larva or a completed animal can be borne without injury.

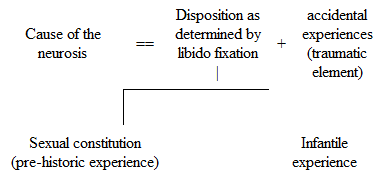

The libido fixation of adults, which we have referred to as representative of the constitutional factor in the etiological comparison of the neuroses, can be thought of, so far as we are concerned, as divisible into two separate factors, the inherited disposition and the tendency acquired in early childhood. We know that a schematic representation is most acceptable to the student. Let us combine these relations as follows:

The hereditary sexual constitution provides us with manifold tendencies, varying with the special emphasis given one or the other component of the instinct, either individually or in combination. With the factor of infantile experience, there is again built up a complementary series within the sexual constitution which is perfectly comparable with our first series, namely, the gradations between disposition and the chance experiences of the adult. Here again we find the same extreme cases and similar relations in the matter of substitution. At this point the question becomes pertinent as to whether the most striking regressions of the libido, those which hark back to very early stages in sexual organization, are not essentially conditioned by the hereditary constitutional factor. The answer to this question, however, may best be put off until we are in a position to consider a wider range in the forms of neurotic disease.

Let us devote a little time to the consideration of the fact that analytic investigation of neurotics shows the libido to be bound up with the infantile sexual experiences of these persons. In this light they seem of enormous importance for both the life and health of mankind. With respect to therapeutic work their importance remains undiminished. But when we do not take this into account we can herein readily recognize the danger of being misled by the situation as it exists in neurotics into adopting a mistaken and one-sided orientation toward life. In figuring the importance of the infantile experiences we must also subtract the influences arising from the fact that the libido has returned to them by regression, after having been forced out of its later positions. Thus we approach the opposite conclusion, that experiences of the libido had no importance whatever in their own time, but rather acquired it at the time of regression. You will remember that we were led to a similar alternative in the discussion of the Oedipus-complex.

A decision on this matter will hardly be difficult for us. The statement is undoubtedly correct that the hold which the infantile experiences have on the libido – with the pathogenic influences this involves – is greatly augmented by the regression; still, to allow them to become definitive would nevertheless be misleading. Other considerations must be taken into account as well. In the first place, observation shows, in a way that leaves no room for doubt, that infantile experiences have their particular significance which is evidenced already during childhood. There are, furthermore, neuroses in children in which the factor of displacement in time is necessarily greatly minimized or is entirely lacking, since the illness follows as an immediate consequence of the traumatic experience. The study of these infantile neuroses keeps us from many dangerous misunderstandings of adult neuroses, just as the dreams of children similarly serve as the key to the understanding of the dreams of adults. As a matter of fact, the neuroses of children are very frequent, far more frequent than is generally believed. They are often overlooked, dismissed as signs of badness or naughtiness, and often suppressed by the authority of the nursery; in retrospect, however, they may be easily recognized later. They occur most frequently in the form of anxiety hysteria. What this implies we shall learn upon another occasion. When a neurosis breaks out in later life, analysis regularly shows that it is a direct continuation of that infantile malady which had perhaps developed only obscurely and incipiently. However, there are cases, as already stated, in which this childish nervousness continues, without any interruption, as a lifelong affliction. We have been able to analyze a very few examples of such neuroses during childhood, while they were actually going on; much more often we had to be satisfied with obtaining our insight into the childhood neurosis subsequently, when the patient is already well along in life, under conditions in which we are forced to work with certain corrections and under definite precautions.

Secondly, we must admit that the universal regression of the libido to the period of childhood would be inexplicable if there were nothing there which could exert an attraction for it. The fixation which we assume to exist towards specific developmental phases, conveys a meaning only if we think of it as stabilizing a definite amount of libidinous energy. Finally, I am able to remind you that here there exists a complementary relationship between the intensity and the pathogenic significance of the infantile experiences to the later ones which is similar to that studied in previous series. There are cases in which the entire causal emphasis falls upon the sexual experiences of childhood, in which these impressions take on an effect which is unmistakably traumatic and in which no other basis exists for them beyond what the average sexual constitution and its immaturity can offer. Side by side with these there are others in which the whole stress is brought to bear by the later conflicts, and the emphasis the analysis places on childhood impressions appears entirely as the work of regression. There are also extremes of "retarded development" and "regression," and between them every combination in the interaction of the two factors.

These relations have a certain interest for that pedagogy which assumes as its object the prevention of neuroses by an early interference in the sexual development of the child. So long as we keep our attention fixed essentially on the infantile sexual experiences, we readily come to believe we have done everything for the prophylaxis of nervous afflictions when we have seen to it that this development is retarded, and that the child is spared this type of experience. Yet we already know that the conditions for the causation of neuroses are more complicated and cannot in general be influenced through one single factor. The strict protection in childhood loses its value because it is powerless against the constitutional factor; furthermore, it is more difficult to carry out than the educators imagine, and it brings with it two new dangers that cannot be lightly dismissed. It accomplishes too much, for it favors a degree of sexual suppression which is harmful for later years, and it sends the child into life without the power to resist the violent onset of sexual demands that must be expected during puberty. The profit, therefore, which childhood prophylaxis can yield is most dubious; it seems, indeed, that better success in the prevention of neuroses can be gained by attacking the problem through a changed attitude toward facts.

Let us return to the consideration of the symptoms. They serve as substitutes for the gratification which has been forborne, by a regression of the libido to earlier days, with a return to former development phases in their choice of object and in their organization. We learned some time ago that the neurotic is held fast somewhere in his past; we now know that it is a period of his past in which his libido did not miss the satisfaction which made him happy. He looks for such a time in his life until he has found it, even though he must hark back to his suckling days as he retains them in his memory or as he reconstructs them in the light of later influences. The symptom in some way again yields the old infantile form of satisfaction, distorted by the censoring work of the conflict. As a rule it is converted into a sensation of suffering and fused with other causal elements of the disease. The form of gratification which the symptom yields has much about it that alienates one's sympathy. In this we omit to take into account, however, the fact that the patients do not recognize the gratification as such and experience the apparent satisfaction rather as suffering, and complain of it. This transformation is part of the psychic conflict under the pressure of which the symptom must be developed. What was at one time a satisfaction for the individual must now awaken his antipathy or disgust. We know a simple but instructive example for such a change of feeling. The same child that sucked the milk with such voracity from its mother's breast is apt to show a strong antipathy for milk a few years later, which is often difficult to overcome. This antipathy increases to the point of disgust when the milk, or any substituted drink, has a little skin over it. It is rather hard to throw out the suggestion that this skin calls up the memory of the mother's breast, which was once so intensely coveted. In the meantime, to be sure, the traumatic experience of weaning has intervened.