полная версия

полная версияThe Notting Hill Mystery

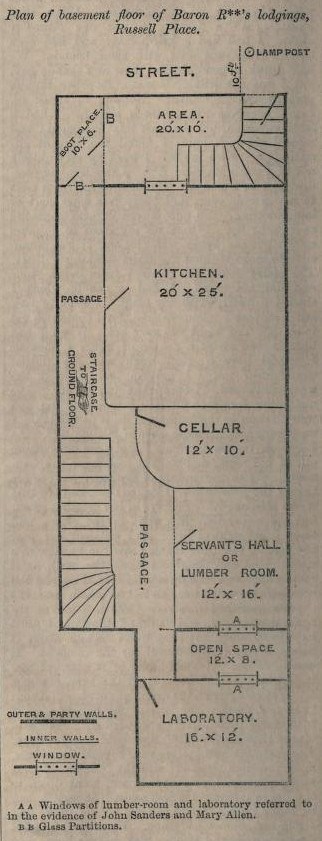

N.B. – The statement of the "young man" referred to fully corroborates the above statement. The accompanying plan will make this witness' evidence more clear.

Plan of basement floor of Baron R**'s lodgings, Russell Place.

Windows of lumber-room and laboratory referred to in the evidence of John Sanders and Mary Allen. B B Glass Partitions.

9. —Copy of a letter from a leading Mesmerist to the compiler, with reference to the power claimed by mesmeric operators over those subjected to their influence.

"Dorset Square."My DEAR SIR, —

"… Many times after throwing Sarah Parsons into the mesmeric state, I have willed her to go into a dark room and pick up a pin or other article equally minute, and however powerless she might be at the time out of the state was quite immaterial. My will and power being employed was sufficient. Then, Mr. L – , a paralytic, under my influence, without losing consciousness or undergoing any recognisable change, has many times, with the lame leg, stepped up on to and down again from an ordinary dining-room chair. This of course was a masterpiece of mesmeric manipulation. I wish I could write more and better, but my eyes forbid * * *

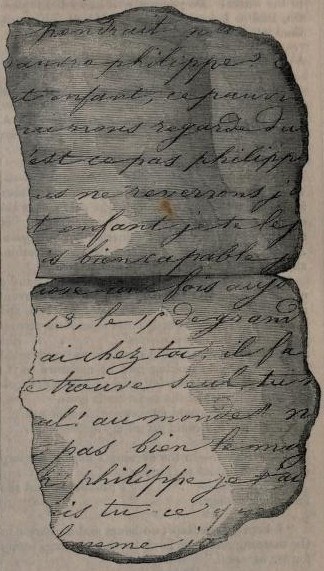

"With kindest regards,"Yours most truly,"D. HANDS."10. —Fragment of a Letter found in the Baron's room after the death of Madame R**.

COMPLETED.

…On (?)

te… pendrait n'e… st ce pas mon

p…auvre philippe? E…h bien par

ce…t enfant, ce pauvre … petit ange (?)

q… ui nous regarde du… haut du ciel,

n'…est ce pas philipp…e et que

no…us ne reverrons ja…mais, par

ce…t enfant je te le j…ure. Tu m'en

sa…is bien capable j…e crois.

En…core une fois, aujo…urd'hui c'est

le… 13, le 15, de grand…matin je

se…rai chez toi; il fa…ut que je

t…e trouve seul, tu … me comprends;

se…ul au monde! n'… en sais

tu … pas bien le moy…en?

O…h! philippe je t'ai…me (je t'aime?)

sa…is tu ce qu…e c'est qu'une

f…emme ja…louse?

Translation of above.

(They) would hang thee, would they not, my poor Philip? Well, by that child – that poor (little angel) who is now – is it not so, Philip? – looking down on us from heaven, and whom we shall never see again, by that child I swear it to you. Once more. To-day is the 13th. On the 15th very early in the morning I shall be at your house. I must find you alone – you understand me, alone in the world! Do you not well know the means? Oh, Philip, I love thee (I love thee). Knowest thou what a jealous woman is?

11. —Extracts from the "Zoist Magazine," No. XLVII., for October, 1854.

"MESMERIC CURE OF A LADY WHO HAD BEEN TWELVE YEARS IN THE HORIZONTAL POSITION, WITH EXTREME SUFFERING. By the Rev. R. A. F. Barrett, B.D., Senior Fellow of King's College, Cambridge.

* * * * *"In January, 1852, I was calling upon – , when she happened to tell me that she had been in considerable pain for a fortnight past; that the only thing that relieved her was mesmerism; but the friend who used to mesmerise her was gone.

"… I continued to mesmerise her occasionally for some months…

"April 21 st.– I kept her asleep an hour and a quarter in the morning and the same in the evening. She said31 her throat looked parched and feverish; at her request I ate some black currant paste, which she said moistened it… She said, 'Before you ate, my stomach was contracted and had a queer-looking sort of moisture in it; now the stomach is its full size and does not look shrunk, and part of the moisture is gone.'

"I. 'But you could not get nourishment so?' "A. 'Yes: I could get all my system wants.'

* * * * *"April 26th.– In the evening I kept her asleep one hour, and took tea for her.

"April 27th.– … I ate dinner and she felt much stronger.

* * * * *"I kept her asleep two hours and a quarter in the morning and one hour in the evening, eating for her as usual."

SECTION VIII. CONCLUSION

There now only remains for me, in conclusion, to sum up as briefly and succinctly as possible the evidence contained in the preceding statements. In so doing, it will be necessary to adopt an arrangement somewhat different from that which has been hitherto followed. Each step of the narrative will therefore be accompanied with a marginal reference to the particular deposition from which it may be taken.

First then, for what may be called the preliminary portions of the evidence. With these we need here deal but very briefly. They consist almost entirely of letters furnished by the courtesy of a near relation of the late Mrs. Anderton I., and read as follows:

Some six or seven and twenty years ago, the mother of Mrs. Anderton – Lady Boleton – after giving birth to twin daughters, under circumstances of a peculiarly exciting and agitating nature, died in child-bed. Both Sir Edward Boleton and herself appear to have been of a nervous temperament, and the effects of these combined influences is shown in the highly nervous and susceptible organisation of the orphan girls, and in a morbid sympathy of constitution, by which each appeared to suffer from any ailment of the other. This remarkable sympathy is very clearly shown in more than one of the letters I have submitted for your consideration, and I have numerous others in my possession which, should they be considered insufficient, will place the matter, irregular as it certainly is, beyond the reach of doubt. I must request you to bear it particularly and constantly in mind throughout the case.

Almost from the time of the mother's death, the children were placed in the care of a poor, but respectable woman, at Hastings. Here the younger, whose constitution appears to have been originally much stronger than that of her sister, seems to have improved rapidly in health, and in so doing to have mastered, in some degree, that morbid sympathy of temperament of which I have spoken, and which in the weaker organisation of her elder sister, still maintained its former ascendency. They were about six years old when, whether through the carelessness of the nurse or not, is immaterial to us now, the younger was lost during a pleasure excursion in the neighbourhood. Every inquiry was made, and it appeared pretty clear that she had fallen into the hands of a gang of gipsies, who at that time infested the country round, but no further trace of her was ever after discovered.

The elder sister, now left alone, seems to have been watched with redoubled solicitude. There is nothing, however, in the years immediately following Miss C. Boleton's disappearance having any direct bearing upon our case, and I have, therefore, confined my extracts from the correspondence entrusted to me, to two or three letters from a lady in whose charge she was placed at Hampstead, and one from an old friend of her mother, from which we gather the fact of her marriage. The latter is chiefly notable as pointing out the nervous and highly sensitive temperament of the young lady's husband, the late Mr. Anderton, to which I shall have occasion at a later period of the case, more particularly to direct your attention. The former give evidence of a very important fact; namely, that of the liability of Miss Boleton to attacks of illness equally unaccountable and unmanageable, bearing a perfect resemblance to those in which she suffered in her younger days sympathetically with the ailments of her sister; and, therefore, to be not improbably attributed to a similar cause.

Thus far for the preliminary portion of the evidence. The second division places before us II. certain peculiarities in the married life of Mrs. Anderton; its more especial object, however, being to elucidate the connection between the parties whose history we have hitherto been tracing, and the Baron R**, with whose proceedings we are properly concerned.

It appears then, that in all respects but one, the married life of Mr. and Mrs. Anderton was particularly happy. Notwithstanding their retired and often somewhat nomad life, and the limits necessarily imposed thereby to the formation of friendships, the evidence of their devoted attachment to each other is perfectly overwhelming. I have no less than thirty-seven letters from various quarters, all speaking more or less strongly upon this point, but I have thought it better to select from the mass a small but sufficient number, than to overload the case with unnecessary repetition. In one respect alone their happiness was incomplete. It was, as had been justly observed by Mrs. Ward, most unfortunate that the choice of Miss Boleton should have fallen upon a gentleman, who however eligible in every other respect, was, from his extreme constitutional nervousness, so peculiarly ill-adapted for union with a lady of such very similar organisation. The connection seems to have borne its natural fruit in the increased delicacy of both parties, their married life being spent in an almost continual search after health. Among the numerous experiments tried with this object, they at length appear to have had recourse to mesmerism, becoming finally patients of Baron R**, a well known professor of that and other kindred impositions.

Mrs. Anderton had not been long under his care when the remonstrances of several friends led to the cessation of the Baron's immediate manipulations, the mesmeric fluid being now conveyed to the patient through the intervention of a third party. Mademoiselle Rosalie, "the medium" thus employed, was a young person regularly retained by Baron R** for that purpose, and of her it is necessary here to say a few words.

She appears to have been about the age of Mrs. Anderton, though looking perhaps a little older than her years; slight in figure, with dark hair and eyes, and in all respects but one answering precisely to the description of that lady's lost sister. The single difference alluded to, that of wide and clumsy feet, is amply accounted for by the nature of her former avocation. She had been for several years a tight-rope dancer, &c., in the employ of a travelling-circus proprietor; who, by his own account, had purchased her for a trifling sum, of a gang of gipsies at Lewes, just at the very time when the younger Miss Boleton was stolen at Hastings by a gang whose course was tracked through Lewes to the westward. Of him she was again purchased by the Baron, who appears, even at the outset, to have exercised a singular power over her, the fascination of his glance falling on her whilst engaged upon the stage, having compelled her to stop short in the performance of her part. There can, I think, be little doubt that this girl Rosalie was in fact the lost sister of Mrs. Anderton, and of this we shall find that the Baron R** very shortly became cognisant.

It does not appear that on the first meeting of the sisters he had any idea of the relationship between them. He was, indeed, perfectly ignorant of the early history of both. The extraordinary sympathy therefore which immediately manifested itself between them was not improbably set down by him as a mere result of the mesmeric rapport, and it was not till he had been for some weeks in attendance on Mrs. Anderton that accident led him to divine its true origin. Nor, on the other hand, does this singular sympathy – a sympathy manifested in a precisely similar manner to that known to have existed years ago between the sisters – appear to have raised any suspicion of the truth in the mind of either Mrs. Anderton or her husband. From the former, indeed, all mention of her early life had been carefully kept till she had probably almost, if not entirely, forgotten the event, while the latter merely remembered it as a tale which had long since ceased to possess any present interest.

The two sisters were thus for several weeks in the closest contact, the effects of which may or may not have been heightened by the so-called mesmeric connection between them, before any suspicion of their relationship crossed the mind of any one. One evening, however, – and from certain peculiar circumstances we are enabled to fix the date precisely to the 13th of October, 1854, – the Baron appears beyond all doubt to have become cognisant of the fact. I must request your particular attention to the circumstances by which his discovery of it was attended.

On that evening the conversation appears to have very naturally turned upon a certain extraordinary case professed to be reported in a number of the "Zoist Mesmeric Magazine," published a few days before. The pretended case was that of a lady suffering from some internal disorder which forbade her to swallow any food, and receiving sustenance through mesmeric sympathy with the operator, who "ate for her." From this extraordinary tale the conversation turned naturally to other manifestations of constitutional sympathy, as an instance of which Mr. Anderton related the story of Mrs. Anderton's lost sister, and the singular bond which had existed between them. The conversation appears to have continued for some time II., 2., and in the course of it a jesting remark was made by one of the party in allusion to the story of eating by deputy, to which I am inclined to look as the key-note of this horrible affair.

"I said," deposes Mr. Morton, "I said it was lucky for the young woman that the fellow didn't eat anything unwholesome."

From the moment these words were spoken the Baron appears to have dropped out of the conversation altogether. More than this, he was clearly in a condition of great mental pre-occupation and disturbance. Mr. Morton goes on to describe the singularity of his manner, the letting his cigar expire between his teeth, and the tremulousness of his hands, so excessive, that in attempting to re-light it he only succeeded in destroying that of his friend. There can, I think, be no doubt whatever that from that moment he believed thoroughly in the identity of Rosalie with the lost sister of Mrs. Anderton. What other ideas the conversation had suggested to him we must endeavour to ascertain from the evidence that follows.

On the morning of the day succeeding that on the evening of which he had become convinced of Rosalie's identity, we find Baron R** at Doctors' Commons inquiring into the particulars II., 5. of a will by which the sum of 25,000l. had been bequeathed, under certain conditions, to the children of Lady Boleton. Under the provisions of this will, the girl Rosalie was, after her sister and Mr. Anderton, the heir to this legacy. We need, I think, have no difficulty in connecting the acquisition of this intelligence with the steps by which it was immediately followed. Mr. Anderton at once received an intimation of the Baron's approaching departure for the continent, and at the end of the third week from that time leave was taken, and he apparently started upon his journey. In point of fact, however, his plans were of a very different character. During the three weeks which intervened between his visit to Doctors' Commons and his farewell to Mr. Anderton, there had been advertised in the parish church of Kensington the banns of marriage between himself and his "medium," Rosalie, – not, indeed, in the names by which they were ordinarily known, and which would very probably have excited attention, but in the family name – if so it be – of the Baron and in that by which Rosalie was originally known when with the travelling circus. By what means he prevailed upon his victim to consent to such a step is not important to the matter in hand. The general tenour of the subsequent evidence shows clearly that it must have been under some form of compulsion, and, indeed, the unfortunate girl seems to have been made by some means altogether subservient to his will.

The marriage thus secretly effected, the Baron and his wife leave town, not for the continent, as stated to Mr. Anderton, but for Bognor, an out-of-the-way little watering-place on the Sussex coast, deserted save for the week of the Goodwood races, where, at that time of the year, he was not likely to meet with any one to whom he was known. Before endeavouring to investigate the motive of all this mystery, it is necessary to bear in mind one important fact: —

Between the wife of Baron R** and Mr. Wilson's legacy of 25,000l., the lives of Mr. and Mrs. Anderton now alone intervened.

The first few days of the Baron's stay in Bognor seem to have been devoted to the search for a servant, he having insisted on the unusual arrangement of himself providing one in the house where he lodged. It is worthy of note that the one finally selected was in a position, with respect to character, that placed her entirely in her master's power. It is unfortunate that this same defect of character necessarily lessens the value of evidence from such a source. We must, however, take it for what it is worth, remembering at the same time, that there is a total absence of any apparent motive, save that of telling the truth, for the statement she has made.

It appears, then, from her account, that after trying by every means to tempt her into some repetition of her former error, the Baron at last seized upon the pretext of her taking from the breakfast table a single taste of jam upon her finger, to threaten her with immediate and utter ruin. One only loop-hole was left by which she could escape. The alternative was, indeed, most ingeniously and delicately veiled under the pretext of seeking a plausible reason for her dismissal; but, in point of fact, it amounted to this, that as a condition of her alleged offence not being recorded against her, she would own to the commission of another with which she had nothing whatever to do.

The offence to which she was falsely to plead guilty was this. On the night succeeding the commission of the fault of which, such as it was, she was really guilty, Madame R** was taken suddenly ill. The symptoms were those of antimonial poisoning. The presence of antimony in the stomach was clearly shown. In the presence of the medical man who had been called in, the girl was taxed by the Baron with having administered, by way of a trick, a dose of tartar emetic; and she, in obedience to a strong hint from her master, confessed to the delinquency, and was thereupon dismissed with a good character in other respects. Freed from the dread of exposure, she now flatly denies the whole affair, both of the trick and of the quarrel which was supposed to have led to it, and I am bound to say, that looking both to external and internal evidence, her statement seems worthy of credit.

Nevertheless the poison was unquestionably administered. By whom?

Cui bono? Certainly, it will be said, not for that of the Baron; for until at least the death of Mr. and Mrs. Anderton his interest was clearly in the life of his wife. It is not, therefore, by any means to be supposed that he would before that event attempt to poison her. Of this mystery, then, it appears that we must seek the solution elsewhere.

Returning then for a time to Mr. and Mrs. Anderton, we find that the latter has also suffered from an attack of illness. Comparing her journal III. and the evidence of her doctor, with that given in the case of Madame R**, it appears that the symptoms were identical in every respect, with this single but important exception, that in this case there is no apparent cause for the attack, nor can any trace of poison be found. A little further inquiry, and we arrive at a yet more mysterious coincidence.

It is a matter of universal experience, that almost the most fatal enemy of crime is over-precaution. In this particular case the precautions of the Baron R** appear to have been dictated by a skill and forethought almost superhuman, and so admirably have they been taken, that, save in the concealment of the marriage, it is almost impossible to recognise in them any sinister motive whatever. His course with respect to the servant girl, though dictated, as we believe, by the most criminal designs, is perfectly consistent with motives of the very highest philanthropy. Even in the concealment of the marriage, once granting – as I think may very fairly be granted – that such a marriage might be concealed without any necessary imputation of evil, the means adopted were equally simple, effective, and unblameable. They consisted merely in the use of the real, instead of the stage names of the contracting parties, and in the very proper avoidance of all ground for scandal by hiring another lodging, in order that before marriage the address of both parties might not be the same. In the illness of Madame R**, too, at Bognor, nothing can, to all appearance, be more straightforward than the Baron's conduct. He at once proclaims his suspicion of poison, sends for an eminent physician, verifies his doubts, administers the proper remedies, and dismisses the servant by whose fault the attack has been occasioned. Viewed with an eye of suspicion, there is indeed something questionable in the selection of the medical attendant. Why should the Baron refuse to send for either of the local practitioners, both gentlemen of skill and reputation, and insist on calling in a stranger to the place, who in a very few days would leave it, and very probably return no more? Distrust of country doctors, and decided preference for London skill, furnishes us, as usual, with a prompt and plausible reply. It does not, however, exclude the possibility that the expediency of removing as far as possible all evidence of what had passed may have in some degree affected the choice. Be that as it may, this precaution, whether originally for good or for evil, has enabled us to fix with certainty a very important point.

Mrs. Anderton was taken ill, not only with the same symptoms, but at the same time, with Madame R**.

Before proceeding to consider the events which followed, there are one or two points in the history of this first illness of the sisters on which it is needful to remark. The action of these metallic poisons, among which we may undoubtedly rank antimony, is as yet but very little understood. We know, however, from the statements of Professor Taylor,32 certainly by far the first English authority upon the subject, that peculiarities of constitution, or, as they are termed, "idiosyncracies," frequently assist or impede to a very extraordinary extent the action of such drugs. The constitution of Madame R** appears to have been thus idiosyncratically disposed to favour the action of antimony. There can be no doubt that the action of the poison upon her system was very greatly in excess of that which under ordinary circumstances would have been expected from a similar dose. The poison, therefore, by whomsoever administered, was not intended to prove fatal, though from the peculiar idiosyncracy of Madame R** it was very nearly doing so.

The narrowness of Madame R**'s escape seems to have struck the Baron, and to have exercised a strong influence over his future proceedings. Whether or not he knew or believed her to be exposed to any peculiar influences which might tend to render her life less secure than that of her delicate and invalid sister, it is impossible positively to say. There was no question, however, that her death before that of Mrs. Anderton would destroy all prospect of his succession to the 25,000l., and with this view he proceeded to take as speedily as possible the necessary steps to secure himself against such an event. The obvious course, and indeed that suggested at once by Dr. Jones, was that of assurance, and this course he accordingly adopted, after having previously, by a tour of several months, restored his wife to a state of health in which her life would probably be accepted by the offices concerned. The insurances, therefore, with which we are concerned, were effected in consequence of a previous administration of poison to Madame R**, producing an illness far more serious than could have been anticipated, and accompanied by precisely similar symptoms on the part of her delicate sister, Mrs. Anderton, whose death, if preceding that of Madame R**, would more than double the Baron's prospect of succession.

Between him, therefore, and the sum of either 25,000l. or 50,000l. there now intervened three lives, those of Mr. and Mrs. Anderton, and of his own wife, Madame R**, and on the order in which they fell depended the amount of his gain by their demise. The death of Mr. Anderton before that of Mrs. Anderton, would open the possibility of a second marriage, from which might arise issue, whose claim would precede his; that of his own wife preceding that of either Mr. or Mrs. Anderton, would destroy altogether his own claim to the larger sum. It was only in the event of Mrs. Anderton's death being followed first by that of her husband, and afterwards by that of her sister, that the Baron's entire claim would be secured.