полная версия

полная версияHorses Past and Present

“… Gentlemen went on breeding their horses so fine for the sake of shape and speed only. Those animals which were only second, third or fourth rates in speed were considered to be quite useless. This custom continued until the reign of Queen Anne, when a public spirited gentleman (observing inconvenience arising from this exclusiveness) left thirteen plates or purses to be run for at such places as the Crown should appoint. Hence they are called the King’s or Queen’s Plates or Guineas. They were given upon the condition that each horse, mare or gelding should carry twelve stone weight, the best of three heats over a four-mile course. By this method a stronger and more useful breed was soon raised; and if the horse did not win the guineas, he was yet strong enough to make a good hunter. By these crossings – as the jockeys term it – we have horses of full blood, three-quarters blood, or half bred, suitable to carry burthens; by which means the English breed of horses is allowed to be the best and is greatly esteemed by foreigners.”

Whether the money for the royal plates was provided, as Berenger states, from the Queen’s own purse, at the instance of her consort, or whether it came from the estate of the public spirited gentleman referred to by the contributor to the Sporting Magazine, the fact remains that these plates were established in Anne’s reign, and that they did something to encourage the production of a better stamp of horse. An animal able to carry twelve stone three four-mile heats must be one of substance, and not merely a racing machine.

Much attention would seem to have been given to the mounting of our cavalry and the general efficiency of that arm by Anne’s generals. Col. Geo. Denison, in his History of Cavalry (London, 1877), says that the battle of Blenheim in 1704 was almost altogether decided by the judicious use of cavalry, while at Ramillies in 1706, and Malplaquet, the cavalry played a very important part in the operations.

In the later years of her reign the Queen’s interest in racing became still more apparent; she gave her first Royal gold cup, value 60 guineas, in 1710; and yet more plates: further, she ran horses in her own name at York and elsewhere.

There was little change on the “Road” during Anne’s time; springs of steel had replaced the leather straps used in England until about 1700, but the coaches, improved in minor details, were still ponderous and required powerful teams to draw them. The Queen’s own state coach was drawn by six mares of the Great Horse, or as it should be called in connection with the period under survey, the Shire Horse breed. Oxen were used in the slow stage waggons, as appears from the laws passed by William III. and Anne. The law of the latter sovereign (6 Anne, cap. 56) enacted that not more than six horses or oxen might be harnessed to any vehicle plying on the public roads except to drag them up hills; and this latter indulgence was withdrawn three years later (1710), leaving the team of six to negotiate hills as they might. Hackney coachmen evidently displayed a tendency to evade their legal obligations in the matter of size in their horses; for in 1710 another Act (9 Anne, c. 16) was passed to the same effect as a former law, requiring hackney-coach horses to be not less than 14 hands in height.

GEORGE I. (1714-1727)

During the first seventy years of the eighteenth century Eastern horses were imported in large numbers; there is in existence a list of 200 stallions which were sent to this country, but that number does not represent a tithe of the whole. The event of George I.’s reign, from a Turf point of view, was, of course, the arrival, in 1724, of the Godolphin Arabian, the sire to which our racers of to-day owe so much. George I. appears to have taken little personal interest in the Turf, though at least one visit paid by him to Newmarket, in October 1717, is recorded; nor does the parliamentary history of his brief reign show that much attention was given to the work of improving our horses.

The science of travel had gone back rather than forward, for in 1715 the post from London to Edinburgh took six days, whereas in 1635 it took three. At this time, and until 1784, the mails were carried by boys on horseback; and between the badness of the roads, the untrustworthiness of the boys, and the wretched quality of the horses supplied them, the postal service was both slow and uncertain. The Post Office still held the monopoly (first granted in 1603) of furnishing post-horses at a rate of threepence a mile, and its control over its subordinates was of the slightest.

The only Act of George I.’s reign relating to horses was that of 1714 (1 George I., c. 11), which forbade waggoners, carriers, and others, from drawing any vehicle “with more than four horses in length.”

The omission of reference to oxen in this connection may indicate that for draught purposes on the highways they were going out of use.

GEORGE II. (1727-1760)

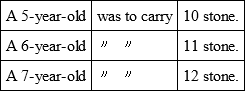

An important step was taken in regard to the Turf by George II. in 1740; some of its provisions will be found in Ponies Past and Present (pp. 8 and 9), but it contained other clauses of a far-reaching character. This law (13 Geo. II., c. 19) provided that every horse entered for a race must be bonâ fide the property of the person entering it, and that one person might enter only one horse for a race on pain of forfeiture. The weights to be carried were prescribed:

Any horse carrying less was to be forfeited and his owner fined £200. Every race was to be finished on the day it began, that is to say, all heats were to be run off in one day. The Act went even further. It declared that matches might be run for a stake of under £50, only at Newmarket and Black Hambleton in Yorkshire, under a penalty of £200 for disobedience. Prizes elsewhere were to be of an intrinsic value of at least £50, and entrance money was to go to the second horse.

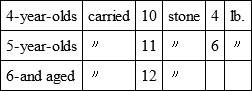

So drastic a measure as this could not long be upheld in a free and sport-loving country; and it is without surprise we find the Government, five years later, withdrawing from a position which must have made it excessively unpopular. The next law (18 Geo. II., c. 34, sec. xi.) opens with the announcement that, whereas the thirteen Royal Plates of 100 guineas value each, annually run for, as also the high prices that are continually given for horses of strength and size are sufficient to encourage breeders to raise their cattle (sic) to the utmost size and strength possible, “Therefore it shall be lawful to run any match for a stake of not less than £50 value at any weights whatsoever and at any place or places whatsoever.”

The effect of this “climbing down” measure was naturally to introduce lighter weights. Thus in 1754, to take an example that presents itself, Mr. Fenwick’s Match’em won the Ladies’ Plate of 126 guineas at York carrying nine stone, as a five-year-old; six-year-olds carrying 10 stone, four-mile heats; and in 1755 Match’em beat Trajan at Newmarket carrying 8 stone 7 lbs. Perhaps it is not too much to say that the Act of 1745 was the first step towards modern light-weight racing. It must be added that the scale of weights prescribed for the Royal Plates was as follows: —

Races decided in 4-mile heats.

The King himself lent a somewhat perfunctory support to the Turf, keeping at Hampton Court a grey Arab stallion, whose services were available for mares at a stated fee.

A most important event in the history of the Turf marks George II.’s reign. The Jockey Club was founded, and its existence first received public recognition in Mr. John Pond’s Sporting Kalendar, published at the end of 1751 or the beginning of 1752. It is probable, however, that the club was actually in existence in the year 1750; but it was started without any attempt at publicity, and, so far as can be ascertained, with no idea whatever of acquiring the despotic power which eventually came into its hands. As Mr. Robert Black, in The Jockey Club and its Founders, remarks:

“What more natural than that the noblemen and gentlemen who frequented Newmarket, where ruffians and blacklegs were wont to congregate, should conceive the notion of forming themselves into a body apart, so that they might have at Newmarket as well as in London and elsewhere a place of their own, to which not every blackguard who could pay a certain sum of money would have as much right as they to claim entrance.”

The conjecture is a most plausible one; but it was not long before the Club showed that it intended to support racing in practical fashion, for at the Newmarket meeting in May, 1753, two Jockey Club Plates were given for horses belonging to members of the Club.

It is stated that, in the year 1752, sixty thoroughbred stallions, of which only eight were reputed imported Arabs, were standing for service in various parts of England; fees, as may be supposed, were low. A horse named Oronooka headed the list at a fee of 20 guineas; another, Bolton Starling, covered at 8½ guineas; but the usual charge was one, two or three guineas. Flying Childers in the earlier part of the century stood at 50 guineas, then at 100 guineas, and one season at 200 guineas.

There is little to note concerning the “Road” or other spheres of equine work during this reign. The roads were as bad as ever, and travel was so slow that in 1740 Metcalf, the blind road-maker, walked the 200 miles from London to Harrogate more quickly than Colonel Liddell could cover the distance in his coach with post-horses. The barbarous methods of training cavalry recruits at this period was attracting notice, as we learn from a little work on Military Equitation, by Henry Earl of Pembroke, which was published in 1761. The writer refers to the “wretched system of horsemanship at present prevailing in the army,” and refers to the common method of putting a man on a rough trotting horse, “to which he is obliged to stick with all his might of arms and legs.” Most of the officers, he says, when on horseback are a disgrace to themselves and the animals they ride; and he proceeds to urge the adoption of methods based on practical common sense.

GEORGE III. (1760-1820.)

The laws concerning horses made by the Parliaments of George III. have bearing on the subject of breeding and improvement, inasmuch as they deal with the horse as taxable property. The turf, road, and hunting history of the reign is important, the first particularly so, though the King himself took little personal interest in racing. “Give and Take” plates for horses from 12 to 15 hands were in fashion during the latter part of the last century, George II.’s Act directed against small racehorses notwithstanding. A 12-hand pony carried 5 stone, and the scale of weight for inches prescribed 14 oz. for each additional quarter of an inch; whereby 13 hands carried 7 stone, 14 hands 9 stone, 15 hands 11 stone. Hunter races were run at Ascot in 1722, and after that date the Calendar of 1762, however, is the first of the series that contains the form of “Qualification for a Hunter.”

The Royal Plates were still among the most important events of the Turf; in 1760 there were 18 of these in England and Scotland, and 6 in Ireland, 5 of the latter in Kildare. The “King’s Plate Articles,” which appear in every annual issue of the Racing Calendars for very many years, were retained in their original form. “Six-year-olds shall carry 12 stone, 14 lbs. to the stone; three heats”; but in the Calendar of 1773 a footnote occurs, “By a late order altered to one heat.” Nevertheless, very cursory inspection of the books shows that much latitude was allowed in weights, distances, and numbers of heats both before 1773 and after. In 1799 another footnote appears under the “King’s Plate Articles,” to effect that the conditions “By a late order are altered to one heat and different weights are appointed.” In spite of this order races for the plates were on occasion still run in two or three heats, apparently by permission of the Master of the Horse. We are not informed what weight the new scale required, but the pages of the Calendar show they were reduced; authoritative information on the point appears with the Articles at a later date. In 1807 the number of Royal Plates had been increased to 23 in Great Britain.

On the 4th May, 1780, the first Derby was run; the value of the stake was 50 guineas, and the race, open to three-year-old colts at 8 stone, and fillies at 7 stone 11 lbs., distance one mile, was won by Diomed. In 1801, 1803, 1807, and 1862, the weights for the Derby were altered, always increasing by a few pounds, till they reached their present level. By 1793, the Derby had grown into great popularity. The establishment of the St. Leger, in 1776, and the Oaks in 1779, are events which also aid to make King George III.’s reign memorable. Races for Arab produce occur on the Newmarket “cards” about the time our classic races were founded; sweepstakes of 100 guineas being run for in 1775, 1776, and 1777. Races for Arabs, however, have never been continued for many years in succession.

The accompanying portrait of Grey Diomed, a son of Diomed, the winner of the first Derby, in 1780, gives a good idea of the racehorse of this period. Grey Diomed was foaled in 1785, and won many important races between the years 1788 and 1792. He was bred at Great Barton, Bury St. Edmunds, by Sir Charles Bunbury.

It was in 1780 that Mr. William Childe, of Kinlet, “Flying Childe,” introduced the modern method of riding fast to hounds. Prior to Mr. Childe’s time, men rode to hounds in a fashion we should consider slow and over-cautious, timber being taken at a stand; but once the superior excitement of fast riding across country was realised, the old, slow method soon disappeared.

Though the Norfolk Hackney achieved its fame through Blaze (foaled 1733), who begat the original Shales, foaled in 1755, and the foundations of this invaluable breed were thus laid in George II.’s time, we must have regard to the period during which the breed achieved its celebrity both at home and abroad, and that period is the long reign of George III.

The old system of conveying mails on horseback, with its innumerable faults and drawbacks, came to an end in George III.’s time, a mail coach making its first trip in August, 1784, when the journey from Bristol to London, about 119 miles, was performed in 17 hours, or at a rate of 7 miles per hour. The era of macadamised roads, which was followed by the short “golden age” of fast coaching, can hardly be said to belong to this reign, Mr. Macadam’s system of road-making having been generally adopted only in 1819.

The founding of the Royal Veterinary College at Camden Town in 1791 was by no means the least important event of this reign; it is not too much to say that it marked an epoch in the history of the Horse; for the establishment of this institution made an end of the quackery, often exceedingly cruel, which for centuries had passed for medical treatment of animals. Until the end of the eighteenth century English veterinary practitioners had been content to follow in the footsteps of such teachers as Gervaise Markham, who was the great authority on equine diseases two hundred years before; and the principles and practice of Gervaise Markham were hardly free from the taint of witchcraft and sorcery. Some of the more drastic and obviously useless remedies had been discredited and abandoned, but at the period of which we write, English veterinarians appear to have been following their own way regardless of the more enlightened methods which were beginning to gain acceptance among the advanced practitioners of France. For to the French is due the credit of laying the first foundations on which scientific veterinary surgery was built.

The helplessness of the old school is proved by the ravages of epizootics. The loss of horses and other live stock when contagious disease gained footing was enormous, such diseases being entirely beyond the understanding of veterinarians. The last half of the eighteenth century saw the establishment of veterinary colleges in Europe. Lyons led the way in 1761; the next to be founded was that of Alfort near Paris in 1765; the next, Copenhagen, in 1773; Vienna, 1775; Berlin, 1790, and London, as already mentioned, in 1791.

Study of animal diseases was stimulated by the invasion of deadly plagues, which wrought such havoc that stock-raising in some countries threatened to disappear as an industry. Knowledge of these plagues and efficient remedies had become essential to the existence of horse and cattle breeding, and the collection of facts and correct views concerning such diseases was the greatest task of the veterinary colleges: the progress made was necessarily slow; but the foundation of veterinary surgery as a science dates from the establishment of the colleges named. For many years the new school of veterinarians were groping in the dark; but if they made no striking advance they did valuable work in collecting facts and correct views concerning animal diseases, which were of great value to a later generation.

The Royal Veterinary College was founded by a Frenchman named Charles Vial de St. Bel, or Sainbel. Sainbel was born at Lyons in 1753. His talents developed early in life, and after a brief but brilliantly successful career in France he came over to England in 1788. He published proposals for founding a Veterinary School in this country, but his suggestions were not favourably received, and he returned home. Perhaps the fact that he had married an Englishwoman during his short residence on this side of the Channel influenced Sainbel in his choice of refuge when the Revolution threatened; but however that may be, it was to London that he repaired when political unrest in Paris bade him seek a new sphere of activity.

By a stroke of good fortune Mr. Dennis O’Kelly selected the young French veterinary surgeon to dissect the carcase of the great race-horse Eclipse in February, 1789. Sainbel did the work, and wrote an “Essay on the Geometrical Proportions of Eclipse,” which attracted immediate notice and established his reputation as a veterinary anatomist.

He still cherished his scheme for founding a Veterinary School, and his abilities now being recognised, it was taken up by the Odiham Agricultural Society. In 1791 Sainbel had the satisfaction of seeing the school established, in the shape of a farriery with stabling for fifty horses. He did not live to see the success that was destined to attend his enterprise, as he died in 1793 in his fortieth year. During the two years of his work as principal, however, he had laid down the lines on which scientific veterinary practice should be conducted; in the words of his biographer, “Sainbel may justly be looked upon as the founder of scientific veterinary practice in England” (Dictionary of National Biography).

GEORGE IV. (1820-1830)

In George IV. the Turf had, perhaps, the most ardent supporter it ever boasted among our sovereigns, though the unfortunate Escape affair caused him to renounce the sport altogether for many years (1791-1810): The King was passionately fond of horses, and never wearied of trying hacks and hunters; he got together a splendid breeding stud at Hampton Court. In the last year of his reign he increased the number of Royal Plates to 43, of which 27 were run for in England, Scotland and Wales, and 16 in Ireland: he was also instrumental in bringing about vast improvements in the royal buckhounds. The legislative measures of George IV. were a bill to entirely relieve agricultural horses from taxation, the duties thereon having been reduced by George III. in the last year of his reign; and a bill to relieve horses let for travelling of the duties that had been imposed upon them by his father.

WILLIAM IV. (1830-1837)

William IV. had no great love of racing, and his personal attitude towards the sport is well reflected in his oft-quoted order to “start the whole fleet” for the Goodwood Cup of 1830. He was, however, fully alive to the national importance of racing, and did something to encourage it, presenting the Jockey Club in 1832 with one of the hoofs of Eclipse set in gold, which, with £200 given by himself, was to be run for annually by horses the property of members. “The Eclipse Foot” appears to have brought fields for only four years, and then remained an ornament of the Jockey Club rooms at Newmarket.

In the same year, 1832, a new schedule of weights was appended to the Articles for the King’s Plates; this shows that the weights to be carried varied somewhat according to the places where the races were run. No scale was prescribed for Newmarket, the conditions being left for settlement by the Jockey Club. In 1837, the last year of William’s reign, the number of Royal Plates had again increased and stood at 48, 34 in England and Scotland, 14 in Ireland.

The king continued the breeding stud at Hampton Court which his brother had bequeathed to him; if his affection for the Turf was slight, he deserves the greater credit for having maintained it.

The reign of William IV. saw the coaching age at its best, for rapid travel by road was raised to a science only a few years before its extinction by the introduction of railways. Good roads, good horses and improved coaches in combination rendered it possible to cover long distances at a uniformly high speed, from 10 to 10½ miles per hour being the rate at which the mails ran between London and Exeter, London and York, and other important centres.

HER MAJESTY QUEEN VICTORIA. Acc. June 20, 1837

The sale of the Hampton Court Stud is the first noteworthy event of Her Majesty’s reign. The step taken by the Queen’s advisers, with Lord Melbourne, the Prime Minister, at their head, was deeply regretted by all interested in horse breeding, as one seeming to imply that the national sport would no longer receive the patronage of the Throne. A respectful but strong memorial against the sale was presented by the Jockey Club, but without avail, and on October 25, 1837, Messrs. Tattersall disposed of the stud before a crowded audience, which included buyers from France, Germany, Russia, and other foreign countries. The catalogue included 43 brood mares, which brought 9,568 guineas; 13 colt foals, 1,471 guineas; 18 filly foals, 1,109 guineas; and 5 stallions, including The Colonel and Actæon and two imported Arabs, 3,556 guineas.

Actuated by patriotic motives and unwilling that so fine a horse should go abroad, Mr. Richard Tattersall bought The Colonel for 1,600 guineas; a price which was then considered a very large one. The total realised by sale of the stud, including a couple of geldings, was 15,692 guineas. Thirteen years later, in 1850, the clear-sightedness of H.R.H. the Prince Consort, saw that the dispersal had been a mistake, and that year saw the foundation of a new stud which flourished until 1894, when it was sent to the hammer. Regarding this second dispersal, it was urged that the stud did not pay its expenses; and although it produced The Earl, Springfield and La Flèche, good judges, including the late General Peel, were of opinion that the ground, on which for so many years Thoroughbreds had been reared, was tainted and therefore needed rest.

In 1840 the fifth Duke of Richmond brought in a bill to repeal those clauses of 13 George II. which still remained on the Statute Book limiting the value of stakes, and this measure passed into law, not without opposition (3 and 4 Vic. 5). Some interesting evidence bearing on our subject was given before the Select Committee on Gaming which was appointed in 1844. Mr. John Day gave it as his opinion that the breed of horses had much improved during the twenty to twenty-five years preceding, the improvement being apparent in riding and draught horses. Mr. Richard Tattersall shared Mr. Day’s opinion as regarded improvement, but thought fewer horses were bred. About 1836 or 1837 farmers were in such a state that they could not, or did not think it worth while to breed; by consequence the industry had fallen off and there was a scarcity. Railways, in Mr. Tattersall’s opinion, had affected the market. “The middling sort does not sell in consequence of railways; horses that used to fetch £40 now bring £17 or £18.” Riding horses sold better than the middling class, but hunters did not fetch half the price they did in former years.