полная версия

полная версияReminiscences of a Liverpool Shipowner, 1850-1920

We managed to land our “contemptible” little army (as the Kaiser was pleased to term it) of 170,000 men, and place it in battle array on the Belgian soil without our enemy knowing when it arrived or where it was placed, and it was this ignorance of the whereabouts of our forces which we are now told enabled us to turn the defeat of the Marne into a victory.

On the seas our fleet was able to dispose of the German Pacific fleet by sinking it in the battle off the Falkland Islands. The raiders were, however, successful in destroying much shipping before they were run to earth by our navy, which in the end destroyed or captured them. The credit of destroying the “Cap Trafalgar” after a severe fight belongs to a Liverpool merchant ship, the “Carmania.”

The war, however, developed new engines of maritime warfare – the submarine, the mine, and the seaplane – and our enemies speedily let it be known that they intended to carry out the traditions of their Hun forbears, and pursue a ruthless war, in which they would slay every man, woman and child, however peaceful might be their occupations, if they stood in their way – a policy which they carried out with the greatest cruelty, outraging every dictate of humanity.

The U boats, whose legitimate sphere was only to attack warships or those carrying troops or munitions, broke the laws of nations, and attacked Hospital ships, sinking them with their freight of suffering humanity, passenger steamers, and merchantmen of every kind, not merely sinking them, leaving their people to drown or perish, but in many cases adding to their death struggles by firing upon them while in the water, or turning them adrift in their boats hundreds of miles away from the land.

Germany had realised at an early date in the war that she had no chance of defeating our Navy in regular warfare, and that the submarine was not a very effective weapon against a battleship; and therefore, after declaring a submarine blockade of British commerce, entered upon a submarine campaign against our merchant shipping, in which she met with varying success. Between the 24th February and the 13th October, 1916, she sank 183 ships and 144 fishing vessels, the highest number in one week being 35; and in the following year, between February 26th and November 18th (in nine months) the German submarine sank 661 vessels of over 1,600 tons, 247 under 1,600 tons, and 161 fishing craft; the number of ships unsuccessfully attacked being 550. During the war upwards of 8,000 British sailors lost their lives through submarine attacks.

Submarines which at first were limited in the range of their operations by the amount of fuel they could carry, and could only conduct their nefarious warfare within the waters immediately surrounding Great Britain, were eventually built of sufficient size to be able to destroy our shipping when two or three hundred miles to the west of Ireland, and two or three U boats were constructed large enough to cross the Atlantic and destroy some shipping on the American coast; they were also armed with guns, which they freely used. Various estimates were put out as to the number of submarines afloat. They seemed to ever increase in numbers, and in their boldness and unscrupulous mode of warfare. Sometimes their attacks slacked off, as we are now told, while the Kaiser had passing qualms of conscience. Their movements were directed by wireless, and there is little doubt that they had sympathizers on the British coast, from whom they received information. The sinking of our shipping became alarming, sometimes, at the week-ends, the total reaching twenty and more steamers for the two days.

This was the condition of things with which our merchant fleet had to contend. Traversing day by day and hour by hour waters reeking with death and destruction, they knew that a submarine attack probably meant death to a large number of the people on board, perhaps all; but the British sailors heeded it not, their country’s call sounded in their ears, and without hesitation they went to sea, not only in ships engaged in commerce, but also in vessels acting as armed cruisers and as patrol ships, sweeping the seas in search of the enemy’s raiders; or as transports, in which they conveyed nearly a million of British troops from the most distant parts of the world, and two millions of American troops across the Atlantic, with all their munitions of war and all their impedimenta. Such a brilliant performance must for all time stand forth as one of the greatest achievements in the world’s history. Nor was the great and heroic work of our sailors limited to merchant ships. Our fishing fleets, fitted as minesweepers, carried on without flinching, the highly dangerous task of sweeping the seas to find and destroy the mines which the enemy had strewn in all its pathways. Even their mines were diabolically constructed to destroy innocent life, for contrary to international law, they remained active even after they were detached from their moorings, and were floating about. They were also sown by night, in the busy channels frequented by cross channel steamers and our fishing fleets. That all this was carefully thought out and “according to plan,” is proved by the fact they could and did discriminate where and what their submarines attacked, for the Isle of Man boats were immune from attack, because it was known that they regularly carried large numbers of German prisoners of war. The patrol and mine-sweeping services conducted by our fishermen and many yachtsmen were most arduous, exposed not only to submarines and mines, but to the cruel, cold winter weather and heavy seas; yet they never faltered in their duty.

The sea along the east coast of England is sown with wreckage of steamers and fishing craft destroyed while pursuing their ordinary and innocent trades. The Irish Sea and the North Channel are also strewn with the remains of British shipping. For four years or more British ships followed their calling, passing through seas bristling with dangers, and the people of this country, which depends upon its overseas traffic for their daily bread, went about as usual, and suffered no actual privation from the shortage of food.

Such was the position of things – the dangers which our merchant ships had to encounter, and the problems which our Navy had to attack and to conquer. The versatility of our Navy is proverbial. It has been well said “A sailor is a jack of all trades.”

A distinguished officer recently stated that when he retired from the Navy, he bought a brewery, which he worked for some years, and brewed the best beer in the district. He then laid a submarine cable for the American Government, and ended up by managing a foreign coal-mine. Such is the remarkable adaptability of our naval men. It is not, therefore, surprising that when the submarine menace developed itself our navy was not slow in devising means of counter-attack, and of destroying the U boats. Destroyers and even submarines chased them, dropping depth charges containing high explosives, which were fatal if they struck the submarine, and even the concussion of the explosion at a considerable distance placed their electric batteries hors de combat. Wire netting protected our ships while at anchor, and was used to form a barrier across the Channel and to protect our ports.

It was found that U boats could be seen from an aeroplane when they were some depth under the water. Aeroplanes were, therefore, used to hunt the submarine, and indicate its position to an accompanying destroyer, or the aeroplane itself dropped a depth charge.

Underwater listening apparatus was invented, by which the thud of the propeller of a submarine could be distinctly heard, and the position of the submarine approximately ascertained.

Mystery-ships, fully armed, but having the appearance of an innocent coasting vessel, traversed the adjacent seas, but the most successful protection afforded to our transports and to our commerce was the adoption of the old system of “convoys.” Convoys were seldom very successfully attacked, and ships lost while being convoyed did not exceed 3 per cent. The convoy system required very careful organisation. Ships have different speeds and different destinations, so we had convoys for ships of varying swiftness. We had not sufficient war ships or destroyers to act as convoys from shore to shore in the Atlantic, therefore the convoys crossing the ocean were only under the protection of a ship of war, and only met their escort fleet of destroyers when they reached the danger zone. At a given point the convoy broke up, some ships going up the St. George’s Channel to Liverpool, the others proceeding to London and the Channel ports. The convoy system in the later stages of the war became very perfect, and although some enemy submarines boldly penetrated the protecting line of destroyers, and sank a few ships, they seldom got away again, and the knowledge of this had a very wholesome and a very deterrent effect. The valuable services performed by both English and American destroyers to our Mercantile Marine deserves the highest praise.

The appearance of the River Mersey upon the arrival of a convoy was something to be remembered. Sometimes a convoy would consist of twenty or thirty large merchantmen, all dazzle-painted, stretching out in a long line from New Brighton to the Sloyne, while their escort of British and American destroyers made their rendezvous at the Birkenhead floating stage.

Admiral Scheer, in his book, allows that the Germans lost half of their submarines, a considerable number he says were always under repair, and the difficulty of obtaining crews was an increasing one. Therefore, we think that it can be claimed that our navy had already mastered the U boat menace when the war ended.

To make it difficult for a submarine to find the range at which to fire their torpedos, our ships were carefully camouflaged or dazzle-painted, and presented a very grotesque and strange appearance, no two ships being alike. The painting was carefully designed, in many cases by an artist of eminence, the object being to confuse the eyes of a spectator at a distance. In some cases the ship was made to appear as if going the opposite way to that upon which she was actually proceeding. In others the ship gave the appearance of going at a much greater speed than that at which she was actually steaming. In others the ship at a distance had the appearance of being much shorter than she really was. In all these cases the submarine would have difficulty in ascertaining how far his quarry was away from him, which way she was proceeding, and how fast she was going. In order to render a submarine attack still more ineffective, our ships during the day time followed a zig-zag course, proceeding for a given period on a certain course, then suddenly changing it by several degrees, thus rendering it difficult for a submarine to get into a position to fire a torpedo.

Another device adopted by our ships when pursued by a submarine was to throw out a smoke screen, which for some minutes entirely hid them from the enemy, enabling them to alter their course and steal away from their pursuers.

The promiscuous mine-laying was a source of many disasters, but fortunately the invention of the “paravane” by a naval officer, proved an excellent protection. It consisted of two long steel bars, one on either side of the ship, attached at one end to the bows a few feet below the water, and at the other to an “otter,” which, as the ship proceeded, spread the bars out and kept them away from the ship’s side. When a mine was struck, the buoy-rope of the mine slid down and along the bar, and when it reached the “otter” the rope was caught and cut by a steel knife, and the mine was sunk.

Sufficient has been said to prove the very active and noble part taken by our Mercantile Marine during the war. Although we do not claim that they won the war, we can, at least, say that the war could not have been won without them.

We would also wish to bear testimony to the excellent spirit displayed by the Royal Navy to the Merchant Navy. They were in the highest and best sense “comrades-in-arms,” and we in Liverpool also gratefully recognize our debt to the United States. American destroyers were continually in the Mersey. We admired their seamanlike trim, and the smartness of the officers and crews, and we appreciate the excellent and arduous work they did in safeguarding our convoys, which not only demanded the exercise of great skill, but called forth courage and endurance.

Chapter VI

SHIPPING AND THE WAR

The following Chapter was published during the War, and fairly describes the attitude taken by shipowners towards the War, and the great work they successfully performed1. – Now and AfterIt is unfortunate that no adequate statement has been forthcoming setting before the public the important services shipowners are performing for the country, and the serious position of the shipping industry. Even in the House of Commons the voice of the shipowner has never been effectively raised.

It is no exaggeration to say that the shipping interest of Great Britain has sacrificed more than any other leading industry – and the country does not realise the serious difficulties which are in front of shipowners if they are to “carry on” after the war and maintain our maritime position. Indeed, so far from the true position of the shipowner being realised, there appears to be a general impression that he has made undue profits out of the war, and is still in a privileged position, and is gathering in exceptional riches.

It will scarcely be disputed that the material prosperity of the country depends upon the existence of a great mercantile marine, and that our shipping industry is vital to the existence of the nation. In times of peace we depend upon it to feed and clothe our people, and to bring us the necessary raw products, the manufacturing of which gives employment to our industrial population. We are apt to forget that we live upon an island, and with the exception of coal and iron, we depend almost entirely upon our shipping to supply the wants of our forty-five millions of people and to maintain our industries.

Were it not for our merchant ships the present war could not have been carried on. It would, ere now, have been lost, and the people of this country would be in the grip of famine. Nor have our shipowners merely supplied our commercial wants; our merchant ships have been turned into armed cruisers, patrol ships, hospital ships, and transports, and have thus rendered the most effective assistance in the conduct of the war.

Anyone who realises these facts will see how important it is that our shipping interest should be supported, so that it may be in a position to resume its activities; and that its individuality should not be crushed and extinguished by Government control and bureaucracy. As a proof of the successful enterprise of our shipowners in the twenty years prior to the war, our tonnage increased from 8,653,543 tons to 19,145,140 tons, and we owned 43 per cent. of the world’s shipping.

It may be well to deal at once with the allegation that shipowners have made excessive profits. There is no doubt that during the first two years of the war ships earned large freights, not, however, due to what is commonly called “profiteering,” but simply because the Government hesitated to check the imports of merchandise of a bulky character. After the Government had taken up the tonnage necessary for their transport purposes, what remained was not sufficient to convey the produce pressing for shipment. If imports had been regulated as they are now, the pressure for freight room would have been reduced and freights kept within moderate limits.

The urgent need for checking imports of a bulky character was, I know, urged upon the Government by shipowners who foresaw the scramble for freight space, but the Government failed to respond to these representations. Their hands were very full, the tonnage problem was a new and difficult one, opening up many embarrassing questions, viz., as to what imports should be checked, the effect of this upon our manufacturers, and what would be the result of checking trade in one direction, in causing its dislocation in another, and the consequent disturbance of our foreign exchanges. All these and others were points upon which we had little or no experience to guide us, and the position was aggravated by the loss of tonnage due to the ravages of the submarine.

Taking a calm view of the retrospect, and the gigantic and unique task with which the Government has been faced, they have accomplished their work with fewer blunders than might have been expected. After all, freights have not bulked largely in the increased cost of produce; a freight of £10 per ton is only 1d per pound. If we are to find the true cause of our high cost of living we must look at the inflation and consequent depreciation of our currency, the high rate of wages, and increased spending power of our working classes, and the indifferent harvests of last year in all parts of the world.

The high freights earned by our shipping in 1914, 1915, and part of 1916 naturally caused the value of shipping to rapidly advance. Very few new merchant ships were being constructed; ships were being destroyed, and shipowners possessing established lines were forced to buy to maintain their services, and thus the value of secondhand steamers advanced to two, three, and even four times their pre-war values. Many holders, especially of tramp steamers, sold out and realised great fortunes, and these unexpected and unprecedented profits unfortunately escaped taxation, on the ground that they represented a return of capital; and it is these profits that have appeared unduly large in the public eye.

The shipowners who remained in business, and this comprised the great majority, were deprived of 80 per cent. of all their profits above their pre-war datum, and afterwards this tax on their excess profits was relinquished, and the Government requisitioned all tonnage on what are known as Blue Book rates – which on the basis of the present value of shipping yield only a poor return.

It is difficult to understand why the Government should have placed shipping on a basis of taxation differing from all other industries – it is the industry which beyond all others is essential to the conduct of the war, and which is exceptionally subject to depreciation. The Chancellor of the Exchequer (The Right Hon. A. Bonar Law) was undoubtedly carried away by his own amateur experience as a shipowner, and thought there was no limit to the extent he might filch away the shipowner’s earnings, little recking that if the shipowner is unable to put on one side a reserve to replace the tonnage he loses, he is forced to go out of the trade; and also utterly disregarding the rapid headway being made by neutral countries, who are profiting by the high freights and using their profits to greatly extend their mercantile fleets.

In estimating the financial results of our shipowning industry during the early period of the war, allowance must be made for the increased cost of working a steamer. Coals, wages, insurance, port charges, and cost of repairs, and upkeep were all very high; indeed, it may be said that the nett results to the shipowner of the high freights which prevailed in 1915 and 1916 were not very excessive when all these things are considered, for in addition to the increased cost of working, there was heavy depreciation to provide for, the shipowner suffered a complete dislocation of his trade, and in many cases lost his entire fleet, the creation of long years of toil, and with this his means of making a livelihood.

2. – Difficulties of RestorationWe have considered the position of shipping as the paramount industry of the country – its great services in the conduct of the war, and what it is suffering in consequence of the diffusion of fairy tales of the excessive profits made by shipowners. We can now turn our attention to the extraordinary difficulties which stand in the way of the restoration of the shipping industry, which are fraught with considerable peril to the future of our Empire.

Shipping may be divided into two classes, both of which are of national importance. The liners, which comprise fixed services of passenger and cargo ships. These services must be maintained, and new tonnage built at whatever cost to replace lost ships. The other class is our cargo ships. Many of these conduct regular services; others are what are known as “tramps,” and go where the best freights offer. It is the owners of the tramp steamers who have realised large profits by selling their ships. The Government in their shipping policy have entirely failed to discriminate between these classes, not recognising that the liner services involve a complete and costly system of organisation both at home and abroad, which, once dislocated, is difficult to restore. The urgency for additional cargo ships prevents the building of liners, and there must be a considerable shortage of this description of vessel when the war ends.

Probably the cause which has been most detrimental and disastrous to shipping was the obstinacy of the Admiralty in declining to recognise the urgent necessity for building more merchant ships. They filled all the yards with Admiralty work, and when the violence of the submarine attack aroused the nation to a sense of the danger before it, and the cry went up throughout the land “Ships, ships, and still more ships,” the Government then – only then – responded, and decided that further merchant ships must be built at once. There was great delay in giving effect to their decision to build “standard” ships – plans had to be submitted and obtain the approval of so many officials that many months elapsed before the keel of the first standard ship was laid, and in the meanwhile the losses through the submarine attack continued.

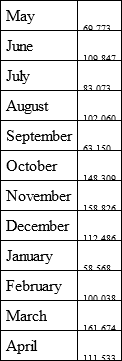

The destruction of tonnage by submarine attack in 1917 assumed very serious proportions, but latterly the number of vessels sunk has been gradually reduced, and we have the recent assurance of the Secretary to the Admiralty that our methods of dealing with submarines have improved, and that we are now achieving considerable success in destroying them. The following statement gives the position to-day in gross tonnage: —

The nett loss of British tonnage of 367,296 tons during the first three months of 1918 was still very serious, but we were told that we were making distinct progress in our rate of shipbuilding, and the following returns seem to bear this out.

The United Kingdom monthly output of new ships from May, 1917, was in tons: —

In the year ended April, 1917, new U.K. ships totalled 749,314 tons, and for the year ended April, 1918, 1,279,337 tons.

The growing scarcity of shipping, the urgent need of providing tonnage for the food supplies, not only for this country, but also for our Allies, forced the Government to consider in what way they could make the most economical use of the tonnage available. The position was rendered more acute by the entry of America into the war, and the adoption of the “convoy” system as a protection against submarine attack.

There were two policies open for adoption by the Government. One was to marshal and organise shipowners, and place in their hands the provision of the necessary tonnage, thus securing the co-operation and assistance of trained specialists. The other policy was to “control” the trade, requisition the whole of our shipping, and to work it themselves. They unfortunately adopted the latter policy, and by so doing they not only lost the individual enterprise and supervision of the trained shipowners, but practically placed shipowners out of business, and this at a time when “neutrals,” who continue to benefit by the high freights, are making rapid strides as shipowners.

The shipping control, under the able direction of Sir Alexander Maclay, is doing its work on the whole better than might have been expected – thanks to the voluntary assistance of many of our younger shipowners. Under the control, the shipowner is paid at rates laid down in the Blue Book, and without going into figures it may be roughly stated that on the pre-war values of steamers these rates leave him 6 per cent. or 7 per cent. on his capital, and 6 per cent. for depreciation, but on to-day’s values the return upon his capital is very poor. A steamer now costs to build at least three times its pre-war cost. Therefore, it is obvious a provision of 15 per cent. for interest and depreciation on pre-war cost is only 5 per cent. on to-day’s values. This affords no inducement to enterprise, and it is not surprising that many shipowners have gone out of business.