полная версия

полная версияA. D. 2000

“Berlin, 19, 8 D. – A great fire is raging at this hour in die Strasse unter den Linden. At 2 D. smoke was seen issuing from the rear windows of the Berlin Art Gallery, and at this hour the building is doomed to destruction. The Berlin Art Gallery was one of the finest buildings in the city, and was, before the institution of the United States of Germany, the palace of the German monarchs. The last Emperor to occupy this palace was William II. grandson of that great and beloved Emperor, William I. By the dethronement of William II., in 1903, all the States which had formed the confederation united under the title of the United States of Germany.”

“St. Petersburg, 19, 9 D. – An imperial ukase has been promulgated granting self-government to all Siberia. By this ukase the Russian Empire loses nearly one-half of its territories. The separation is the outcome of the bitter internal war between the mother country and the distant colonies. Since the discontinuance of exiling to Siberia, which was abolished in 1895, soon after the exposé to the world of the pernicious system and the atrocities practiced by the officials, and after the general amnesty ukase of that year, Siberia has grown in wealth and population to such an extent that self-government comes as a matter of right. Mutual offensive and defensive alliance only is stipulated.”

“Paris, 19, 4 D. – Le Roi est mort. Vive le Roi! The King, Louis XX. is dead. Louis Charles Philippe, great-grandson of Louis Philippe Robert, Duc d’Orleans, and afterward King Louis XVIII., expired at 23 dial of yesterday, after a prolonged and severe sickness. Louis Auguste Stanislaus, Dauphin of France, takes the throne as Louis XXI. Louis Philippe Robert, great-grandfather of Louis XX., ascended the throne in 1894, and reigned until 1917, when the republic was again declared, and Louis XVIII. fled to Naples. After thirteen years the monarchy was reëstablished, and continued until 1951. For twenty-three years did poor France struggle along without the pomp and glitter of an imperial rule; but the strain was too much, and in 1974 the deceased Emperor was summoned to the throne of his forefathers. He proved himself a good sovereign, giving France peace and prosperity.”

“Rome, 19, 5 D. – The Republic of Italy has sent a telegram of condolence upon the death of the French King.”

“Madrid, 19, 5 D. – The Republic of Granada [Spain and Portugal] has sent telegrams of sympathy to the new King of the French.”

“FROM ASIA“Peking, 18, 22 D. – By a royal edict, Li Hung Tsoi, the Emperor, has decreed that, ‘in view of the fact that the good subjects of Tien-tze have for ages worn the emblem of a once distasteful slavery under the Hiong-un, it is now decreed that the ban-ma shall at once be cut from the head of every one of our male subjects, and the chang-mor no longer worn.’ [Ban-ma is the long braided hair worn by all Chinese, and called by us ‘the queue.’ Chang-mor is long hair. – Editor.]”

And then Cobb read on and pondered upon the changes which had taken place, and which he here saw recorded as newspaper items. England, once so proud as a kingdom, now a republic; Germany following in the wake; Spain and Portugal and Italy numbered in the fold. And France! alas! poor France! up and down, changeable as a weather-vane; who could expect a stable government? La belle France! to-day a republic; to-morrow a monarchy!

Turning over the pages of the paper, his eyes lighted up with renewed interest. Though his interest was great as he read of kingdoms falling and new ones building up, here was the page that aroused his old-time enthusiasm. Yes; he was a crank – a crank of the veriest pronounced type, and he knew it as he folded out the paper in his eagerness to read:

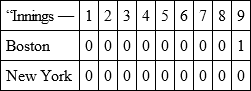

“Boston, 18, 18 D. – The game to-day was a fine exhibition of pitching and fielding. Neither side could score until in the last innings ‘Michael,’ that descendant of the only Mike of the nineteenth century, got his wagon-tongue square against the sphere, and sent it skyward outside of the field.

“The score:

“Errors: none. 2 b. hits: none. 3 b. hits: none. Home run: Michael Kelley. Batteries: for Boston, Clarkson and ‘Ginty’ Carroll; for New York: Keefe and Ewing. Double plays: Boston, 5; New York, 4. Umpire: Sheridan. Time of game: 1:20.”

“The same grand game,” he murmured, “is still the national sport. It could never die! No, never!”

He read on and on. Everything was of interest to him in his new life. He read of himself, of his arrival in Washington, and of his every act during the previous day.

Letting the paper fall from his hand, he aroused Hugh from the perusal of the society columns of the “Washington Reporter” by exclaiming:

“This paper is a great affair, is it not?” nodding toward the paper which had fallen to the floor by his chair.

“A very newsy paper indeed, Junius,” Hugh answered; “in fact, it is the only paper of general news in the United States.”

“How is that? Are there not other newspapers besides this?”

“Oh, plenty. But all others are published for local interests, and rarely circulate outside of their city or township.”

“And you mean to tell me that this paper is the newspaper of the whole country? It must be quite stale ere it reaches many portions of this nation.”

“Not at all. It is simultaneously printed in over five hundred different cities, and no copy has to be sent far to reach its subscriber. For instance: this copy is printed in this city; the copies for New York, in New York; and those for San Francisco, in that town.”

“But the heading reads: ‘America, September 19, 2000?’”

“That is the original paper. At America, the type is set and form made from which copies are taken and reprinted throughout the nation.”

“You astonish me; pray explain yourself.”

“America,” and Hugh wheeled his chair closer to Cobb, “is a small town on the Central Sea, in the old State of Kentucky. All the news of the world is telegraphed to this place, and set in form for printing. Copies of this form are then transmitted by telegraph to every city which is to reproduce the paper – a very simple operation.”

“Yes,” dubiously; “very simple, indeed!”

“But let us not discuss the subject now; I will take you to America, and show you the whole system.”

And the subject of the “Daily American” rested.

At this moment Captain Hathaway entered the room, bowing to both of the gentlemen.

“Good evening, Hugh,” he exclaimed, extending his hand. Then to Cobb: “Good evening, Mr. Cobb.”

“Colonel, sir; Colonel Cobb. You forget you are addressing your superior officer.”

As Hugh spoke, he gave the other a severe look, as if to say, “How do you like it?”

The story of young Hathaway’s discourtesy toward Cobb that morning had been told him.

Captain Hathaway blushed, and turning toward Cobb, said, apologetically:

“I am cognizant of your good fortune and new rank. I congratulate you. You will pardon my rudeness to you this morning, will you not, Colonel Cobb? Some time I will explain why I so far forgot myself,” and he dropped his eyes to the floor.

“Captain Hathaway, let it be forgotten,” frankly extending his hand. “Let us be friends, not enemies.”

Hathaway grasped the hand and wrung it with a sincere grasp of friendship. Then, saluting Cobb, he reported to him for orders.

“You are under orders to join your regiment, are you not?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Do you wish to go?”

“Well, to tell you the truth, there is every reason for wishing to remain; but they will not allow me to do so,” sadly.

“Who will not?”

“The President; for I have applied to him personally.”

“It is rather early for me to go against the wishes of the President,” and he looked at Hugh; “but you are directed to report to me for orders, and I must give them to you.”

“And I must join.” Hathaway spoke in a resigned manner.

“And you will stay in Washington until further orders,” looking at him kindly.

“Colonel, I thank you.”

Cobb had made one more friend.

After an hour at the club, the trio parted; Hathaway to his hotel, and Cobb and Hugh to their rooms.

That night, as he lay upon his bed, Cobb dreamed of Mollie Craft and her radiant beauty, and of Marie Colchis, his child love. The faces of both came in visions before him. He seemed translated to a dark and dreary region, and wandered about sad and alone. No human soul greeted his approach. Alone and desolate of heart, he pursued his way. At last, after ages of misery, he came upon a solitary grave in the desolate waste. Stunted and gnarled, a solitary oak grew at its foot. A headboard, worn and battered by the elements, lay, torn up from its setting upon the ground. A rivulet of water, small and silent in its course, flowed away and sank into the sand.

Moving forward, he read the inscription on the moldy board:

“Junius Cobb and the heart of Marie Colchis.”

With a flood of tears, he threw himself upon the mound, and cried aloud in his anguish:

“O, Marie! Marie! my own, my darling! Oh! come; come to me ere I die!”

A bright light overspread the earth; the desolation seemed to vanish, and all nature assumed its grandest garb. Rising from the grave, he beheld an angel approaching, and leading by the hand a woman in robes of white. Nearer and nearer they drew to his wondering gaze. In the angel’s face he recognized the fair and lovely countenance of Mollie Craft.

“Look up! Behold!” cried the angelic form.

Its companion’s face was raised, and forth she stretched her hands.

With a wild cry of joy, he sprang forward, and was clasped in the arms of Marie Colchis. He saw her ecstatic beauty, her heavenly eyes, her form divine, and felt that she was his once more. Then the voice of the angel, in sweet, harmonious tones, spoke forth the words:

“A bride I bring thee, O sorrowing soul! Those whom God hath made as man and wife, no chance of fate can set apart. Though years and years have fled and passed, yet life shall once again renew her heart!”

CHAPTER XIII

Weeks passed, and Junius Cobb still remained the guest of the President. He investigated the many marvelous subjects which presented themselves to his view. He studied and learned, and became familiar with his new life. He visited New York and other large cities in his vicinity, and noted their growth and progress. He was astonished to find New York a city of over four millions of people, and covering nearly two hundred square miles of territory.

He visited the great tunnels which connect East and West New York to the city proper, Brooklyn and Jersey City having become a corporate part of New York City. The double streets of the city were a wonderful realization of what the needs of a great commercial center will demand of its people. From One Hundredth street south, and over the whole island from the East to the North River, was a double street – a city on top of a city. The lower streets were the originals, and were paved with roughened glass. On one side, covered, and just below the street level, were the great sewers of the city. The height from lower to upper street was twenty feet. In the center of Lower Broadway, Lower Fourth, Sixth, and Ninth Avenues (for such the under streets were designated), and below the level of the pavement, was a double tunnel carrying the rapid-transit electric trains. These trains were composed of light, cylindrical cars, about ten feet in diameter; they had no windows, light being obtained from electricity. The air was received through ventilators, a steady stream of pure, fresh air being kept circulating through the tunnels by immense fans. Automatic indices gave warning of the different stations. The normal speed of these trains was forty miles per hour, and stops were made at every half-mile between Three Hundred and Fifty-third street and the Battery, East New York (Brooklyn); and West New York (Jersey City). Handsome stations along the line, connected by hydraulic lifts with the upper-street stations, enabled the passengers to quickly take the surface lines to all parts of the city. All vehicles devoted to business purposes were confined to the lower streets, and all merchandise, also, was here received and shipped. In the roof of the street were the water-pipes, electric light, telephone, power, and other wires – all easy of access. Like the lower, the upper streets and sidewalks were of glass, which was molded into huge blocks, these resting on steel girders running across and down the streets. The sidewalks were light gray, and the street light steel-color. The thickness of these blocks of glass was four inches, and the light transmitted to the under-street had nearly its natural intensity. On the upper streets, light electric cars ran in every direction, stopping whenever desired. These surface trains were peculiar in that they sat two feet above the pavement, held aloft and in position by two wide but thin rods of steel passing through a slot in the street, the trucks for the cars running upon a roadbed just under the center of the street, or in the roof of the lower street. Upon inquiry, he was informed that the reasons for the elevation of the cars and the subterranean roadway were to avoid accidents; as a person who was so unfortunate as to be struck by a train would be knocked down but passed over by the elevated car without much injury, the steel bars having rounded guards in front to push any object aside. Cobb observed that the entrances to all of the houses, stores, theatres, churches, hotels, etc., were on the upper streets; and also, that access to the lower streets was obtained at every street-corner by flights of broad steps. He noticed that the streets and sidewalks were perfectly clean, and that an air of care, attention, and good order seemed to prevail. Light carriages to horses, electric drags, and such lighter vehicles as are used for transportation of persons only, were alone permitted upon the upper streets. At short distances upon either side of the street were electric lamps, while at one of the corners of each cross-street was a combination post of fine and handsome make. At the base it was about two feet square, decreasing in size to about eight inches at a height of six feet, the whole surmounted by a white glass shaft, twenty-five feet in length. These posts were for a variety of purposes. The lower part contained the carbons, materials, etc., for the electric lights which were placed upon the top; the next compartment was for the reception of mail matter; above these two were the fire-alarm and police boxes, while on either side were the hydrant nozzles. Just under the lamp were the names of the two streets and the ward of the city. The street name was also set into the sidewalk under foot, in different colors – two names on each corner. Red names indicated a north direction; white, east; blue, south; and green, west.

Asking Hugh, who was with him, if they had any improved method of removing the snow during the winter – for he remembered with what difficulty the streets of New York had been cleared of their snow in his time – he was informed that very little snow fell in New York, or, in fact, along the coast as far north as Maine.

“How is that?” exclaimed Cobb, in surprise. “You haven’t changed the seasons, have you?”

“Yes,” nonchalantly.

“What!”

“We have changed the possibility of a frightful winter into the reality of a very even and uniform temperature,” he continued.

“What haven’t you done?”

“Well, we haven’t made a California climate by our work, but we have vastly decreased the severity of our Eastern winters,” he laughingly replied.

“And how have you accomplished this great change?” Cobb asked.

“Here is the Metropolitan Club,” as they came to a grand edifice near Union Square; “let us go in, have a bottle of wine, and I will explain the methods pursued to work this beneficial change of climate.”

“Do you know,” asked Hugh, as he filled two glasses with champagne, after they had become seated in one of the reception-rooms of the club; “do you know why New York and the coast to Nova Scotia is so much colder than the Pacific coast of equal latitude?”

“Certainly. On the Pacific, we have the Kuro Sivo, or Japanese current, touching the coast; while on the Atlantic the Gulf Stream is driven off the coast from about the mouth of the James River, by an arctic current coming around Newfoundland and flowing close to the coast.”

“Exactly. And if this arctic current could be checked, or driven off, then what?”

“Why, the Gulf Stream would bring its waters close to the shore, and the temperature would be raised.”

“That’s it, precisely. And that is just what we have done.”

“How have you done this, pray?”

“The waters of the arctic current,” said Hugh, as he lighted a fresh cigar, and settled himself back in his chair, “come down Davis Strait with icy chillness and sweep around Newfoundland, over the banks and along the eastern coast. This is the main current. By the northerly point of Newfoundland projecting, as it does, into the Atlantic, a second or minor current is evolved which passes through the Straits of Belle Isle. This current, three miles wide by twenty-five fathoms deep, flows at a rapid pace through the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and turns sharp around Cape Breton and flows south. Its icy waters, as they reach the Gulf Stream, chill the latter for miles along the coast, finally disappearing under the stream about the mouth of the James River. If it was not for this minor current, the Gulf Stream would touch our eastern shores to the banks of Newfoundland; of course, more or less chilled by the arctic current, which would impinge upon and sink under the Gulf Stream off the southwest extremity of the banks. Knowing this, we have closed up Belle Isle Strait, save a ship passage.”

“That must have been a huge undertaking,” remarked Cobb.

“Yes, it was. But it was done, nevertheless.”

“How?”

“By very hard and costly work, and very little science. On the southern coast of Labrador, near the straits, are large and vast quarries of granite. Thousands upon thousands of tons of this were quarried out, and when winter came and Belle Isle Straits were frozen over, a double track was laid across the straits, on the ice; large holes cut through, and the granite blocks brought and thrown into the water. Accurate charts were made of each year’s work, so that the material should always fall upon the same line. In four years the work was finished. The sediment brought down by the arctic current soon filled all the interstices, and to-day the dam is perfect, preventing any entrance of the waters of Davis Strait into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, except through a narrow channel for the passage of vessels. Four hundred million cubic feet of material was used in this work.”

Thus, little by little, did Cobb learn of the reasons and wherefores of the many innovations and changes which he constantly saw about him. The days came and passed; Cobb finding delight in the society of Mollie Craft, and pleasure and instruction in that of Hugh, her brother.

And then, when alone, came the dream wherein the angel had led Marie Colchis to him and had spoken the prophetic words. Words prophetic of what? he asked himself. Long and long did he ponder over the vision. His was a nature to love and to desire love in return. To him, woman was an angel, a being divine. Desolate and alone, his heart demanded a companion. He admired Mollie Craft; did he love her? And when he asked the question of himself, he could give no satisfactory reply. But of one fact he felt assured: if he loved her, he loved his lost Marie more. Yet she, his Marie, was dead: was it wrong for him to seek for a companion to soothe the desolation of his heart, especially one embodying such virtues as Mollie Craft? May not the vision have been given for such an interpretation? he argued: he did not know.

One day in the latter part of November, as he and Mollie were sitting by the cheerful fire in the private parlor of the executive mansion, he looked intently into her eyes, and sadly asked:

“Do you not think me sad at times, Mollie?”

He called her Mollie, and she called him Junius; such was the President’s request, as he considered Junius Cobb his adopted son.

“Yes, Junius; and it often pains me to think that, perhaps, we are not doing all that we ought to make your life happy.”

“Would you do more if you could?” and he fixed his eyes with a loving expression upon hers, which fell at his glance.

“I am sure, Junius, that never was a sister – ” and she emphasized the word – “more ready and willing to make a brother happy, than I.”

“Were you ever in love, Mollie?” He jerked the words out as if fearful of the answer she might give.

“Why! what a question!”

“But were you?” he persisted.

“Now, Junius, that is not fair, to ask a girl such a question. Were you ever in love?” She laughed, but anxiously awaited his answer.

“Yes.” He spoke slowly and with an absent air. “Twice have I known what it was to love a woman.”

A tear seemed to glisten in his eye as his memory carried him back a hundred years.

“Twice?” inquiringly.

“Yes; or rather might I say, once to love a woman, and once to love a child.”

“You surprise me greatly, Junius. Will you not make a confidant of me and tell me all about your loves?” and she put her hand upon his shoulder.

That touch, so gentle and light, sent a thrill of pleasure through his heart. He turned and seized her hands in his, and looked long and lovingly into her eyes.

“Can man forswear his soul?” he cried, harshly, while his tight grasp of her hands gave her pain.

“Do not hurt me, Junius!” she cried, trying to free her hands. He released her, and sat down in his chair.

“I did not mean to hurt you, Mollie. I am torn by contending passions of right and wrong. My soul is athirst. I long to quench its burning fires, but dare not speak my thoughts. Alone in a new world, I am barren of kith or kin to fill the aching void in my heart. And, though knowing this, yet am I bound by chains of honor, respect and manly devotion from speaking the words which might, perchance, secure me that greatest of God’s blessings to man, a woman’s love.”

He bowed his head, and remained silent.

Mollie Craft was no child, no affected school-girl, nor hardened society woman. She was a true, noble-hearted being, and read this man’s secret without his lips framing its confession: he loved her.

With sorrow in her voice, she said:

“Junius, you are not alone in the world. You have a father, mother, brother, and sister, though not of the same blood, yet are they as loving as your own relatives could be.”

“I know,” he returned; “but my heart craves more – a being like you, Mollie, to love me and be loved by me in return.”

It was out. He had avowed his love, but not in such passionate terms as one would have used if a reply had been expected. He meant not to ask her heart and hand; he merely told her what his heart craved.

She made no answer; gave no reply.

Then, with a burst of increased sadness, Cobb continued:

“I crave this love, Mollie, but cannot ask for it. I have already given my pledge to a woman – have promised to marry none but her.”

“Then, Junius, you should not break that promise,” and a relieved expression came over the fair face.

“But she can never be mine; she is dead!” and the strong man bowed his head and wept like a child.

Going up to him, she put her arms about his neck, and kissed him on the forehead, then silently left the room.

As the dial in the executive mansion sounded the hour of 22 that night, a figure wrapped in a black cloak stole silently from the rear entrance of the building, through the gardener’s gate and into the conservatory. An instant later and a tall man had clasped her in his arms, and lovingly pressed her to his heart.

“Ah, Lester, you are waiting for me,” looking up into his manly face.

“Yes, dearest; waiting and watching. These moments by your side, stolen though they are, become the happiest in my life. Ah, Mollie! would that you could be with me forever. Why must I thus always beat about the bush to seek your society?”

Reluctantly he released her, but held one dainty hand in his, as he led her to a wicker seat just beside the daisy rows at the lower end of the conservatory and seated himself by her side.