полная версия

полная версияPeru in the Guano Age

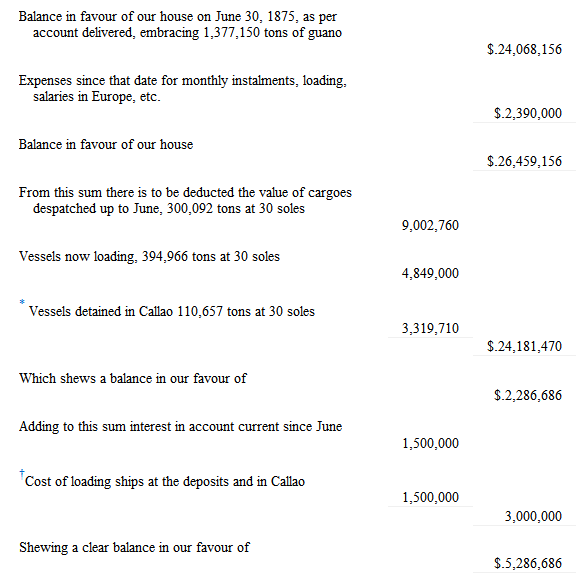

'The Lima press has commented in various articles on the conduct of our house with respect to the export of guano, and we have been charged with endeavouring to appropriate a larger quantity than that which is stipulated in our contracts as sufficient to cover the amounts due to us by the Supreme Government.

These false and malevolent assertions render it necessary for us to satisfy the public and inform the country of the state of our affairs with the Supreme Government.

We trust that dispassionate people who do not allow their opinions to be based on partial evidence, will do our house the justice to which we are entitled by these few particulars, the truth of which is proved by facts and figures that can be authenticated by application to the offices of the Public Treasury.

We have taken thirty soles as the average value of guano of different qualities.

These figures prove that our house not only has not received more than it is entitled to, even if all the vessels had left which are at the deposits as well as those in Callao, but that there is still a heavy balance due to us.

With respect to questions now pending, no one possesses the right to consider his opinions of more value than those of the tribunals of justice before which they now are, without the least opposition on our part.

Dreyfus, Hermanos, & Co.Lima, Dec. 31, 1875.It appears from this statement*, that Dreyfus had already put in their claim for the detention of the ships. What is meant by the last item marked with a † is uncertain; no ships are loaded in Callao. If the Government can sustain its suit against Dreyfus on that part of the second article of the contract mentioned above, instead of its owing Dreyfus the 'clear balance of 5,286,686 dols.' Dreyfus is in debt to the Government.

But there is another item in the second article which appears to override the first: viz. 'y este (guano) será colocado por cuenta y riesgo del gobierno abordo de las lanchas destinadas a la carga de dichos buques' [or, in plain English, 'this guano shall be placed on board such launches as are appointed to carry it to the ships, on account and at the risk of the Government'].

Well, it is absolutely certain that the guano was not colocado, or placed on board the appointed launches; not because the launches were not there; not because there was no guano at the deposits; – but simply because the Government had not, for some reason or other, fulfilled its own part of the contract.

No answer was made by the Government to Dreyfus' circular, and the obsequious Lima newspapers were as silent upon it as dumb dogs. I have since heard, on high authority, that the reply of the Government is prepared, and that it disputes Dreyfus' claims and will contest them in a court of law.

I was glad when they said unto me, let us go to the islands of the north; glad to leave behind me the filthiness, foulness, and weariness of the mainland in the neighbourhood of the Pabellon de Pica. Had it not been for the true British kindness of one or two of my countrymen and several Americans in command of guano ships, Her Majesty's Consular agent, and the agent of the house of Dreyfus, who did all they could to provide me with wholesome food, German beer, and clean beds, I should have fled away from that much-talked-of dunghill without estimating its contents; or like a philosophical Chinaman sought out a quiet nook in the warm rocks, and with an opium reed in my lips smoked myself away to everlasting bliss.

On my return from the south we passed close to the Chincha islands. When I first saw them twenty years ago, they were bold, brown heads, tall, and erect, standing out of the sea like living things, reflecting the light of heaven, or forming soft and tender shadows of the tropical sun on a blue sea. Now these same islands looked like creatures whose heads had been cut off, or like vast sarcophagi, like anything in short that reminds one of death and the grave.

In ages which have no record these islands were the home of millions of happy birds, the resort of a hundred times more millions of fishes, of sea lions, and other creatures whose names are not so common; the marine residence, in fact, of innumerable creatures predestined from the creation of the world to lay up a store of wealth for the British farmer, and a store of quite another sort for an immaculate Republican government. One passage of the Hebrew Scriptures, and this the only passage in the whole range of sacred or profane literature, supplies an adequate epitaph for the Chincha islands. But it is too indecent, however amusing it may be, to quote.

On Sunday morning, March 26th, of the last year of grace, I first caught sight of the beautiful pearl-gray islands of Lobos de Afuera, undulating in latitude S. 6.57.20, longitude 80.41.50, beneath a blue sky, and apparently rolling out of an equally blue sea. Here is the only large deposit that has remained untouched; here you may walk about among great birds busy hatching eggs, look a great sea-lion in the face without making him afraid, and dip your hat in the sea and bring up more little fishes than you can eat for breakfast.

There are eight distinct deposits in an island rather more than a mile in length and half a mile in width. The amount of guano will be not less than 650,000 tons.

It is not all of the same good quality, for considerable rain has at one time fallen on these islands. Wide and deep beds of sand mark in a well defined manner the courses of several once strong and rapid streams. But if the poor guano, that namely which does not yield more than two per cent. of ammonia be reckoned, the deposits on these islands will reach a million tons.

The wiseacres who believe guano to be a mineral substance, and not the excreta of birds, will do well to pay a visit to Lobos de Afuera. There they will see the whole process of guano making and storing carried on with the greatest activity, regularity, and despatch. The birds make their nests quite close together: as close and regular, in fact, as wash-hand basins laid out in a row for sale in a market-place; are about the same size, and stand as high from the ground. These nests are made by the joint efforts of the male and female birds; for there is no moss, or lichen, or grass, or twig, or weed, available, or within a hundred miles and more: even the sea does not yield a leaf. As a rule, about one hundred and fifty nests form a farm. It has been computed by a close observer that the heguiro will contribute from 4 oz. to 6 oz. per day of nesty material, the pelican twice as much. When there are millions of these active beings living in undisturbed retirement, with abundance of appropriate food within reach, it does not require a very vivid imagination to realise in how, comparatively, short a time a great deposit of guano can be stored.

Will the Government of Peru occupy itself in preserving and cultivating these busy birds? That Government has lived now on their produce for more than thirty years; why should it not take a benign and intelligent interest in the creatures who have continued its existence and contributed to its fame?

The heguiro is a large bird of the gull and booby species, but twice the size of these, with blue stockings and also blue shoes. It does not appear to possess much natural intelligence, and its education has evidently been left uncared for. It will defend its young with real courage, but will fly from its nest and its one or two eggs on the least alarm. This, however, is not always the case. But in a most insane manner if it spies a white umbrella approaching, it sets up a painful shriek. Had it kept its mouth shut, the umbrella had travelled in another direction. As the noise came from a peculiar cave-like aperture in the high rocks, I sat down in front, watched the movements of the bird, who kept up a dismal noise, evidently resenting my intrusion on her private affairs. After a brief space I marched slowly up to the bird, who, when she saw me determined to come on, deliberately rose from her nest, and became engaged in some frantic effort, the meaning of which I could not guess. When I approached within ten yards of her, she sprang into the sky and began sailing above my head, trying by every means in her power to scare me away. When I reached the nest, I found the beautiful pale blue egg covered with little fishes! The anxious mother had emptied her stomach in order to protect the fruit of her body from discovery or outrage, or to keep it warm while she paid a visit to her mansion in the skies.

Birds have ever been a source of joy to me from the time that I first remember walking in a field of buttercups in Mid Staffordshire, some fifty years ago, and hearing for the first time the rapturous music of a lark. Since then I have watched the movements of the great condor on the Andes, the eagle on the Hurons, the ibis on the Nile, the native companion in its quiet nooks on the Murray, the laughing jackass in the Bush of Australia, the curaçoa of Central America, the tapa culo of the South American desert, the albatross of the South Pacific. I can see them all still, or their ghosts, whenever I choose to shut my eyes, a process which the poets assure us is necessary if we would see bright colours. And now I no longer care for birds. I have seen them in double millions at a time, swarming in the sky, like insects on a leaf, or vermin in a Spanish bed. They are as common as man, and can be as useful, and become as great a commercial speculation as he.

We visited the island of Macabi, lat. 7.49.30 S., long. 79.28.30, for the purpose of seeing what good thing remained there that was worth removing in the way of houses, tanks and tools for use on the virgin deposits of Lobos de Afuera. Although there is not more than one shipload of guano left, I was glad to see the place for many reasons. It will be recollected that it was on the guano said to exist on this and the Guañapi islands that the Peruvian Loan of 1872 was raised, and it will be the duty of all who invested their money in that transaction to enquire into the truth of the statements on which the loan was made.

Macabi is an island split in two, spanned by a very well constructed iron suspension bridge a hundred feet long. The birds which had been frightened away by the operations of the guano-loading company have returned. The lobos probably never left the place, the precipitous rocks and the great caverns which the sea has scooped out affording them sufficient protection from the 'fun'-pursuing Peruvian, who delights in killing, where there is no danger, an animal twice his own size, and whose existence is quite as important as his own. Or if the lobos did leave, they also have returned. This would go to prove the statements that the birds have begun to return to the Chinchas. When this is proved beyond any doubt, we may expect to hear of Messrs. Schweiser and Gnat applying for another loan on the strength of the pelicans, ducks and boobies having returned to their ancient labours on those celebrated islands.

The spectacle presented at Macabi was humiliating. The ground was everywhere strewn with Government property, which had all gone to destruction. The shovels and picks were scattered about as if they had been thrown down with curses which had blasted them. I went to pick up a shovel, but it fell to pieces like Rip Van Winkle's gun on the Catskills; the wheelbarrows collapsed with a touch. Suddenly I came on a little coffin, exquisitely made, not quite eighteen inches long. There it lay in the midst of the burning glaring rocks, as solitary and striking as the print of a foot in the sand was to Robinson Crusoe. The coffin was empty, and the presence of certain filthy-fat gallinazos high up on the rocks explained the reason. A little further on were the graves of some fifty full-grown persons, 'Asiatics,' probably, who had purposely fallen asleep. Walking down the steady slope of the island till I came to the edge of the sea, which rolled below me some hundred and twenty feet, I came suddenly in front of a thousand lobos, all basking in the sun after their morning's bath. It was a sight certainly new, entertaining, and instructive. The young lobos are silly little things, and look as if it had not taken much trouble to make them; a child could carve a baby lobo out of a log, that would be quite as good to look at as one of these. But the old fathers, patriarchs, kings, or presidents of the herd, are as impressive as some of Layard's Assyrian lions. Suddenly one of these caught me in his eye, and no doubt imagining me to be a Peruvian, signalled to the rest, who, following his lead, all rushed violently down the steep place into the sea, and began tumbling about and rolling over in the surf like a mob of happy children gambolling among a lot of hay-cocks in a green field. They live on fish, and the number of fishes is as great at Macabi as elsewhere. As I remained watching these swarthy creatures, a great sea-lion appeared above the surface of the rolling deep looking about him, his mouth full of fishes, just as you have seen a high-bred horse with his mouth full of straggling hay, turn his head to look as you entered his stable door.

My next and longer visit was to Lobos de Tierra, lat. S. 6.27.30, the largest guano island in the world, being some seven miles long, or more. Here are great deposits of guano, the extent and value of which are not yet known. It is certain that there are more than eight hundred thousand tons of good quality in the numerous deposits which have been hitherto examined.

On January 31st, being in lat. S. 7.50.0, and some 15 miles from the Peruvian coast, when on my way to the South from Panama, we ran into a heavy shower of rain. Now it is much more likely to rain in lat. S. 6.27.30 and 120 miles from the shore, and this explains the reason why the guano deposits of Lobos de Tierra were not worked before. Still the quantity of rich material found there is great, and it is the only place where I came on sal ammoniac in situ; the crystals were large and beautifully formed, but somewhat opaque. During the ten days I remained there, more than 500 tons of good guano were shipped in one day, and there were some 40 ships waiting to receive more.

Like all the other guano deposits, Lobos de Tierra has to be supplied at great expense from the mainland with everything for the support of human life. It is true that the sea supplies very good fish, but man cannot live on fish alone, at least for any length of time, especially if he is engaged in loading ships with guano. The Changos, however, a race of fishermen on the Peruvian coast, do live on uncooked fish, and a finer race to look at may not be found; the colour of their skin is simply beautiful, but they are very little children in understanding. It is only fair to say that with their raw fish they consume a plentiful amount of chicha, a fermented liquor made from maize, the ancient beer of Peru: and very good liquor it is, very sustaining, and, taken in excess, as intoxicating as that of the immortal Bass. These hardy fishers visit all these islands in their balsas, great rafts formed of three tiers of large trees of light wood, stripped and prepared for the purpose in Guayaquil. They are precisely the same as those first met with by Pizarro's expedition when on his way to conquer Peru, three centuries and a half ago. The people are probably the same, except that they now speak Spanish, and are never found with gold; but now and then they do traffic in fine cottons, spun by hand, now as then, by natives of the country.

I cannot forget that it was at Lobos de Tierra I had the great pleasure of forming the acquaintance of one who represents young Peru: the new generation that, if time and opportunity be given it, may transform that land of corruption into a new nation. Here on this barren island, I found a son of one of the oldest Peruvian families, thoroughly educated, well acquainted with England and its literature, proud of his country, jealous for its honour, and keenly alive to the disgrace into which she has been dragged by the wicked men who have gone to their doom. Should this generation, represented by one whom I am allowed to call my friend – who, though born in the Guano Age is not of it, – rise into power, the rising generation in England may see what many have had too great reason to despair of, namely, a South American Republic, that shall prefer death to dishonour, and if needs must, will live on bread and onions in order to be free of debt. There is so much pleasure in hoping the best of all men, that it surely must be a duty the neglect of which, when there are substantial evidences to support it, must be a crime.

I left Lobos de Tierra with profound regret, but it was necessary to do so in order to see what remained to be seen of the precious dung in other parts of Peru. The following will be found to be a fair approximation of the quantities existing along the northern coast.

I have not visited all these small deposits, and have been content to take the report of Captain Black, the chief of the Peruvian expedition lately appointed to examine them. I have found him so faithful and trustworthy in those cases – the more important of them all – where I have had the opportunity of comparing his calculations with my own, that I have not hesitated to adopt his estimates of the least important deposits. I have considered them of value if for no other reason than to guard the public against any fresh discovery being made by interested parties.

If then we add these northern deposits to those of the south, Peru has at present in her possession, in round numbers, 7,500,000 tons of guano of 2240 lbs. to the ton.

It is not my business to suggest the possible existence of guano remaining to be discovered. I may however be allowed to say that there are certain unmistakable indications of even large deposits which may lie buried a hundred feet below the sand on the slopes of the southern shore. As those indications are the result of my own observation, I may be allowed to keep them to myself for a more convenient season.

CHAPTER IV

'However long the guano deposits may last, Peru always possesses the nitrate deposits of Tarapaca to replace them. Foreseeing the possibility of the former becoming exhausted, the Government has adopted measures by which it may secure a new source of income, in order that on the termination of the guano the Republic may be able to continue to meet the obligations it is under to its foreign creditors.'

These words form part of an assuring despatch from Don Juan Ignacio Elguera, the Peruvian Minister of Finance, to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and was made public as early as possible after it was found that the January coupon could not be paid. The assurance came too late for any practical purposes, and it merely demonstrated the fact that the Peruvian Government shared in the panic which had been designedly brought to pass by its enemies as well as its intimate friends in Lima, and their emissaries in London and Paris.

The despatch demonstrates two or three other matters of importance. We are made to infer from its terms, and the eagerness with which it insists on the undoubted source of wealth the Government possesses in the deposits of nitrate, that it was unaware of the actual amount of guano still remaining in the deposits of the north and the south. We may also safely believe that the Peruvian Government did not at the time of the publication of the despatch, dream of asking the bondholders to sacrifice any of their rights; and further, in its anxiety to save its credit with England, it was hurried into a confession which it now regrets.

What spirit of evil suggested to President Pardo the idea of appealing to the charity of his creditors, immediately after allowing his finance minister to announce to all the world that the Republic was able to continue meeting its obligations to its foreign creditors even though the guano should give out, it does not much concern us to enquire. The effect of such an appeal cannot fail to be prejudicial to the credit of Peru; and men or dealers in other people's money will not be wanting who will call in question the good faith of the finance minister when he declared that the deposits of nitrate could continue what the deposits of guano had begun but failed to carry on.

Other considerations press themselves upon us. In the midst of the crisis, the President published a decree, announcing that he would avail himself of the resolution of Congress which enabled him to acquire the nitrate works in the province of Tarapaca. A commission of lawyers was at once despatched to the province to examine titles, and to fix upon the price to be paid to each manufacturer for his plant and his nitrate lands. In an incredibly short time no less than fifty-one nitrate makers had given in their consent to sell their works to the Government, and the price was fixed upon each, and each was measured, inventoried, and closed. The total sum to be paid for these establishments was 18,000,000 dols. But they remained to be conveyed. The civil power had displayed considerable activity; now that the law had to be applied things became as dull as lead, and as heavy as if they had all been made of that well-known metal. Negotiations had also to be entered into with the Lima Banks, which is an operation as delicate and as dangerous as negotiating with so many volcanoes, or any other uncertain and baseless institutions of which either nature or a civilisation supported by bits of paper can boast.

Still the world was comforted by the promise that next week all would be well, or the week after, or say the end of the month, in order to be sure. In the midst of this, General Prado, the possible future President of Peru, is despatched to Europe on a mission, the nature of which was kept a profound secret for three weeks.

Simple men, who believed in the despatch of the finance minister, knew for certain that General Prado had gone to England to raise more money on nitrate, in order that the Oroya Railway might be finished, and a station-house built somewhere in the Milky Way, which it is destined probably this marvellous line shall ultimately reach. And if London would only lend Peru, say another £10,000,000, then Lima would rejoice, and the whole earth be glad; the mountains would break out into psalms, and the valleys would laugh and sing, for would not Don Enrique Meiggs, the Messiah5 of the Andes, once more return to reign?

At any rate it is quite certain that General Prado was announced to sail on the 14th of March, when the last stroke of the pen was to be put to the conveyance of the nitrate properties. Alas! the law's delay continued, and General Prado did not sail. It is natural to suppose at all events that Prado never meant to go to London without the nitrate contracts in his pocket – which will supply a larger income to Peru than the guano in all its glory ever did, – for the purpose of asking the bondholders to be merciful. The General finally left Callao for Europe on the 21st, amidst the forebodings of his friends, and the ill-concealed joy of his foes, but without the nitrate documents being signed. Still, before he could reach London the thing would be done, and the result could be telegraphed. In the meantime the new minister to Paris and London, Rivaguero, telegraphed to Lima some favourable news, the precise terms of which, of course, were not allowed to transpire, to the effect that an arrangement had been made satisfactory to all parties.

On this, further delay takes place in the important nitrate negotiations, and that in the face of a semi-official communication to the effect that next week merchants might rely upon it that all would be well and truly finished. In the stead of this, President Pardo 'reminds the Banks of an item which up to that period had never been dreamed or thought of, except by the President himself, namely, that they, the Banks, on the security of the nitrate bonds, would have to supply to the Government so many hundred thousand dollars per month!

All at once the whole fabric of the nitrate business fell down.

Two things may be inferred from this: President Pardo hoped, believed, perhaps knew, that the bondholders would give way, and he had become convinced that he had made a mistake in buying the nitrate properties; it is also likely that he knew for certain at this time that there was guano enough for all purposes, without meddling with the important nitrate matters, and thereby destroying a great and important national industry. He may also have been desirous to bury, in an oblivion of his own making, the honest compromise contained in the despatch of Don Juan Ignacio Elguera. A further light may have dawned on the Presidential mind, namely, that it will be perfectly easy for the Government to treble the export duty on nitrate, without in the least damaging the trade or dangerously interfering with the profits of the makers, by which means the Peruvian Government would reap an annual income without trouble, or any of the thousand vexations to which it has been subjected in the export and sale of its guano.