Полная версия

Left for Dead?

So in every direction by the 1990s, whether it was economic, social or ideological, the world seemed to have given way beneath social democracy’s feet. The postwar social democratic settlement seemed to be increasingly unobtainable because the pillars on which it had been constructed were vanishing. Callaghan could see what was happening better than anyone. When polls indicated he might be doing a bit better in the run-up to the 1979 election than he might have hoped, his aide, Bernard Donoghue, ventured to suggest he might win after all. ‘Bernard,’ the old warhorse replied, ‘I’m afraid to say I think there’s been a sea change and it is for Mrs Thatcher.’

It is sometimes spoken of as if Blair and Brown ‘abandoned’ socialism all on their own. That’s putting the cart before the horse. By the time New Labour came along the process of abandoning the trappings of the old Attlee settlement (which many people then took, and today continue to take, as the quintessential socialism) was already well underway. Because New Labour was not only an attempt to broaden the party’s sociological appeal: it was also an attempt to respond to a world where traditional methods of social democracy and socialism had been deemed bankrupt, in a metaphorical and a real sense; and many of the people who declared them so were – guess what – the social democratic politicians of the day.

And while the old leftist ways withered the right wasn’t sitting idly by, it was seizing the moment. The next decade and a half after the 1979 election transformed the political and social landscape in Britain, a more economically liberal, individualistic and enterprising culture was born and much of the time Labour was nowhere to be seen. Thatcher clocked up three general election victories and her successor, John Major, secured an unprecedented fourth in 1992.

In the meantime, a betrayal myth developed across some parts of the Labour Party that not only had Blair and Brown sold out but that Wilson and Callaghan had done so before them, that they had given in to international capital, and that if they had taken a properly left-wing approach to managing the economy, things might have been different and Thatcherism might have been resisted. We will never know for certain, but there are two important indicators that might suggest such revisionism is without much basis. The first is that the idea of betrayal might be more credible if similar phenomena were not taking place all across the West. Britain might have led the way, but the entire world was heading in a more ‘neoliberal’ direction. Whether it was Reaganomics in the United States or Rogernomics in New Zealand,‡‡ the picture was much the same everywhere. Even governments that were ostensibly left wing, like François Mitterrand’s in France, implemented more economically liberal policies once in office. The same phenomena that were running the left ragged in Britain were much the same elsewhere; the malaise and stagflation of the 1970s gripped the world; the corresponding decline in social democracy took hold partly as a result of changing technology and work patterns, and partly simply as a result of the final dissipation of some of the solidarity that had so characterised the immediate postwar world. There had, in other words, been an ideological changing of the guard around the world in favour of markets and their creative potential. Just as in the 1940s, the sweep of leftist governments across Europe led the historian A. J. P. Taylor to lament that belief in private enterprise seemed as hopeless as Jacobitism after 1688, so in the 1980s and 1990s did an untrammelled statism appear equally futile.

The left had to respond to these changes and more which were to come: the Soviet Union was collapsing, the Berlin Wall was coming down, and the ideological and geopolitical underpinning of much of twentieth-century leftist thinking was coming down with it. This was the era of the supposed ‘end of history’, as the academic Francis Fukuyama (sort of) said. Liberal market-based democracies had triumphed – it would have been bizarre if no reckoning had come and doubly bizarre if the response had been to double down with policies of nationalisation, higher taxation and stricter economic controls. Indeed, what is striking is that the left responded in a similar way across the West. Wherever you look, whether it’s Clinton’s Democrats or Schroeder’s SDP, there was a conspicuous move to the centre and an acceptance of market methods. New Labour might have embraced it with more brio than the others, but the pattern was the same. The left fundamentally changed because the world around it had done so too, including the attitudes and beliefs of the voters. Thus, even if the dreaded Blair and Brown hadn’t led Labour, even if New Labour had never been created, there is no doubt as to what the direction of the party in the late 1990s would have been because we have a control: the rest of the world. New Labour and Blairism were just a British version of an attempt across the West to respond to the profound crisis of social democracy that had taken place in the late 1970s and beyond.

Blair’s personal take on Labour’s lack of success in the 1980s and 1990s period was a simple one. He told a 1996 BBC documentary analysing the party’s 18 years in the wilderness: ‘The problem of the Labour Party of the seventies and eighties is not complex it’s simple. Society changed and the party didn’t. So you had a whole new generation of people with different aspirations and ambitions in a different kind of world. And we were still singing the same old song that we were singing in the forties and fifties.’7

Brown agreed. He told the same documentary: ‘I don’t think anybody believed that you would have a Conservative government that would be able to maintain itself over four elections and be in power for now 16 years. I think what Mrs Thatcher understood in 1979 was the need for change. I think what Labour failed to understand then was that change had to come about and that Labour should have been sponsoring that change and I think we’ve had to come to terms with that over a period of 16 years.’8

But what would that change look like when all the old tools of tax and spend had been taken out of the toolkit? Well, the truth is, as we shall see, that New Labour did dust off some of the tools in the end – but in the early days, before Brown’s tax hikes of the early 2000s, things were different. Harriet Harman, then shadow chief secretary to the Treasury and Brown’s deputy, described the approach:

Gordon developed the mantra that, to have growth, we needed to build the supply side of the economy. He was determined that our economic policy, which had been our electoral Achilles’ heel over so many years, would shift from taxing and spending the proceeds of growth to focus instead on increasing the rate of economic growth. He wanted to move beyond the idea that our economic policy was only about taxing the rich and spending more on benefits. Government policy should not just be about dividing up the cake but increasing the size of the cake as well. This was the background to his ‘endogenous growth’ speech in 1994, in which he said that economic growth could come not just through increasing demand but through increasing the capacity of the economy by investment in people, through education and training; in industry, through research and development. And in infrastructure, like roads and public transport … This was a huge change. For so long, the only thing people knew about Labour’s approach to the economy was that we would raise taxes and use the money to improve benefits and public services. The public perception was that they would have to pay more taxes and that, subsequently, their money would be thrown down the drain … Now our weekly Treasury team meetings would always begin with Gordon intoning that Labour was not just about taxing and spending but about investment. To get our message across, we had to invoke the supply-side investment strategy as the frame for every point we made.9

This idea, of unleashing people’s latent talent and investing in training and education in order that they might release latent potential was not exactly red-in-tooth-and-claw stuff – it wasn’t bailing out my dad’s job in Rover as the Labour governments of the 1940s and 1960s might have done, but it was still recognisably a Labour innovation. Its transformative impact, on the public realm and on people’s lives, is often underestimated and damned by some on the left and right today who, frankly, would never have come within a thousand feet of feeling its effects. But it was the underlying philosophy that directed government money into my Aim Higher programme and Gifted and Talented. It was the approach that allowed my mum, a woman who had had me at 17 years of age and had had to quit her education early, to retrain as a midwife and start a new life as her kids were growing. It was the philosophy that led to the reinvigoration of the public realm and civic infrastructure that I could see all around me growing up. I’m not convinced that would have happened had New Labour not come to power and the best thinking Conservatives, including David Cameron and his team, learned its lessons. It was a quiet radicalism to befit a benign age.

The irony is, as the government grew in confidence, it quietly became much more bullish about redistribution and the tax and spend policies from which it resiled in its early days. But you wouldn’t have known it; that hushed radicalism led to its own decline.

DIDN’T THEY DO WELL?

Aside from its foreign policy,§§ there are several powerful critiques of the New Labour years. The first is an egalitarian critique. Although the New Labour government can objectively be considered among the most redistributionist and empowering of its predecessors, it was perhaps the first not to place equality as part of its central and organising political mission. This was genuinely new for Labour. The fundamental Labour critique, which underwrote its view of political economy, was that society would not only be better to live in if it were more equal but that it would be more just. It was a profound political insight and one that endured. As early as the late 1990s, senior figures worried the party was drifting away from it and, ergo, the basis of its political and philosophical power. Roy Hattersley, a man partly inspired to become a socialist because of his reading R. H. Tawney’s seminal work Equality as a schoolboy, said in 1995:

We had a big idea, a more equal therefore a better country. Sometimes we called it fairness. Sometimes we called it social justice. But our idea was a more equal and free society. Now that was the idea we should have propagated with determination and consistency and we should sell to the people, the idea we’ve failed to sell to the people. But it’s still the only idea that socialism could possibly stand for.10

It was not entirely clear that Blair and others did share that idea. Equality didn’t improve much in the New Labour years, although there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that it would have got worse than it did had New Labour’s policies not been in place. Regardless, it wasn’t something the leadership seemed very concerned about. Tony Blair famously said that he wasn’t ‘especially interested in controlling what David Beckham earns, quite frankly’. Peter Mandelson likewise observed that New Labour was ‘intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich … as long as they pay their taxes’. Under the Conservatives the Labour rallying cry had always been, just as my grandad used to say to me, that ‘the rich got richer and the poor got poorer’. Under Labour, the poor got richer but the rich got richer too (and faster). For a while it was satisfactory enough, but inspiring rallying call it was not.

The important thing, it was argued, was to create the right conditions that allowed individuals to thrive, that equality of opportunity, not outcome was what mattered. As I’ve said, this isn’t to be underestimated. My life was transformed. I was and am exactly the sort of person Blair’s socialism would benefit. But once I succeeded and had skyrocketed up, the gap in income between me and my old classmates back in Longbridge was something about which New Labour seemed to have little to say, especially in the post-industrial Midlands and north, the small towns and the left behind, what we would one day come to call ‘Brexitland’. That was a clear weakness in New Labour’s political strategy and one that gave its opponents on the left and the right the space to destroy its reputation in years to come – and more importantly, weakened the social and political fabric of the country.

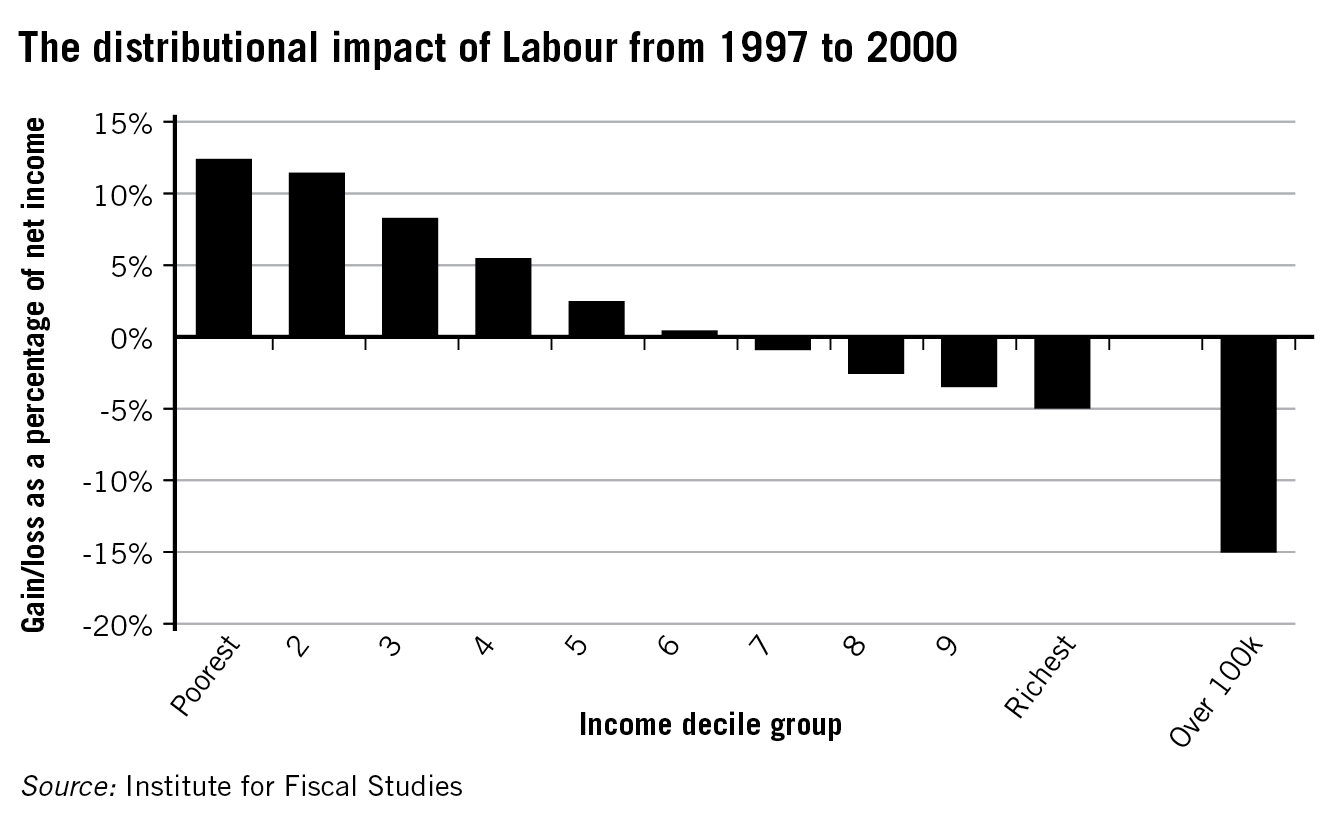

Nonetheless, the last part of the Mandelson quote is still important and often forgotten: that getting filthy rich was acceptable ‘as long as they pay their taxes’. Because, as it turned out, Brown was slowly redistributing vast sums of money, especially after 2002, when he increased National Insurance to pay for greater NHS spending. The tax credit network redistributed money from rich to poor. Take a look at this chart, from the Institute for Fiscal Studies. It shows how much the population gained or lost as a percentage of their income.

The impact is clear. In terms of what the government was doing, there was one sort of person you really didn’t want to be. And it was rich. Quietly, without much fanfare, in a way that it barely dared to say aloud, the New Labour government was redistributing money hand over fist.

But the people who didn’t make a song or dance about it most were the Labour government itself. It was so desperate to appear respectable, not to hark back to Labour governments of long ago, that the most social democratic things they did were never presented as such. They were offered to the country and to their own voters, from conception to implementation, through the way they were explained and communicated, in terms of the market and of individual empowerment. Consequently, what they didn’t do is sew the threads together in a moral critique of capitalism, or of politics more generally. It revelled in its banality, in its dull managerialism. New Labour was often radical but it usually pretended that it wasn’t. Today’s leftists are the opposite. New Labour did social democracy on the quiet, in deed if not in spirit. Corbynism does it through a loudspeaker.

But the sense of mission matters much more than Blair thought it did – as Peter Shore, the former Labour cabinet minister, once said:

‘You’ve always got to have in mind with a Labour Party that if it isn’t a radical party, if it isn’t a party of change, if it isn’t a party that’s committed to making Britain a fairer more equal society then that idealism, that enthusiasm, that energy that goes with that, will be denied it. And if the Labour Party plays too safe for too long then it really will be denying its own heritage.’

Too often, New Labour, desperate to be accepted and to be seen to be in the middle ground, was insufficiently proselytising about just how radical its own achievements were. Looking back it’s clear it was, broadly speaking, a social democratic government. But it didn’t always look or feel that way at the time. As a result, it allowed its internal opponents to cast it as dull technocrats and themselves as the true inheritors of the party’s radical flame. At times, inexcusably, Blair and others acted as if they weren’t political at all. Indeed, he would say in 1999 that ‘I was never really in politics. I never grew up as a politician. I don’t feel myself a politician even now. I don’t think of myself as being a politician in that sense of someone whose whole driving force in life is politics.’ And in so doing he managed to lay the foundations of his own unmaking within the Labour Party.

James Graham’s 2017 play Labour of Love wrestles with recent Labour history and, in so many words, this precise tension. The plot revolves around a Midlands MP, David Lyons, and thirty years of tribulation and trial within the party. In one scene, the MP’s caseworker, Jean Whittaker, offers a killer assessment of the New Labour period: ‘All looks good on the outside but it only takes one little tremor to bring the whole thing down.’ Lyons jumps to the government’s defence, listing all of the new schools and hospitals that have popped up in the area and the new-look town centre, but Whittaker is unimpressed: ‘Yeah, spending, good, fine, but not the actual difficult work of digging deep down into the underlying factors woven into the rotten fabric of this unfair fucking country.’

In other words, New Labour did not in any way challenge the fundamental economic assumptions of the British economy. It believed – as most people did – that at base the British economy was working well and that it was a new sustainable settlement. The basic economic model did not need to be challenged or changed; the sole question was about what you did with the bounty of the untrammelled free market – and New Labour’s answer was, among other things, spend it on kids like me. The problem was, as Whittaker says in the play, that as soon as the good times ended, it was all too easy to turn the taps off. This happened again and again across the West where social democrats had governed. As the academic Shiri Berman told me:

‘These new centre-left politicians celebrated the market’s upsides but ignored its downsides. They differed from classical liberals and conservatives by supporting a social safety net to buffer markets’ worst effects, but they didn’t offer a fundamental critique of capitalism or any sense that market forces should be redirected to protect social needs. When the financial crisis hit in 2008, this attitude repelled those who viewed globalisation as the cause of their suffering and wanted not merely renewed growth, but also less inequality and instability.’

It was all too easy for such measures to be reversed by the Tories, as soon as the good times ended. By contrast, as a signifier of the power of their achievement, Labour did not attempt to reverse the changes to Britain’s political economy that the Tories augured in the 1980s. By way of illustration, Labour’s enduring reforms – which were substantial – were usually structural ones: the Scottish Parliament, the Welsh Assembly, the London mayoralty, the minimum wage, civil partnerships to name but a few. But New Labour was too dewy-eyed about the virtues of the market. As a result, the question Giles Radice posed on that heady day in 1997 is still apposite: ‘What will Tony’s success consist of: election victories or something more permanent? The jury is out.’ The answer, we now know, was somewhere in between. Some permanent structural changes, a reinvigoration of the public realm but not a new settlement in favour of social democracy.

In fairness, it is easy now to say with hindsight what they should have done. Moreover, it seemed before 2008 at least as if New Labour had created a new settlement. When they assumed the leadership of their party, David Cameron and George Osborne did not initially dare to question Labour’s spending. On the contrary, they called on the government to increase spending on public services. It would not even explicitly commit to tax cuts, the raison d’être of Toryism; only cautiously, gingerly, daring to say that they would ‘seek to share the proceeds of growth’ at some undefined point, probably far in the future.

This, as we now know, did not endure. The New Labour settlement was not as successful at changing the minds of its opponents as the Thatcherite one had been. But perhaps one of the reasons for that is Blair himself, who was dedicated not only to the market but to the idea that he wasn’t even political at all. This critique is perhaps the most damaging.

HOOK, LINE AND SINKER

At times New Labour seemed to go out of its way to undermine the very notion of political change itself. So convinced did Blair become about the virtues of the market and of the overweening power of globalisation (and the cultural changes with which it was associated) that New Labour appeared to forget that many of its voters voted Labour to protect themselves from those same forces. Over time, Blair’s rhetoric adopted increasingly determinist and fateful overtones. His interpretation of the globalised world came to imply that political action was barely possible. That was because globalisation was an unstoppable, inexorable force that could be neither halted nor much changed. In conference speech after conference speech a parade of government ministers trotted out the same mantra. Blair’s conference speech of 2005 is the most chilling example:

Change is marching on again. The pace of change can either overwhelm us, or make our lives better and our country stronger. What we can’t do is pretend it is not happening. I hear people say we have to stop and debate globalisation. You might as well debate whether autumn should follow summer.

The character of this changing world is indifferent to tradition. Unforgiving of frailty. No respecter of past reputations. It has no custom and practice. It is replete with opportunities, but they only go to those swift to adapt, slow to complain, open, willing and able to change.

These are not words you’d expect from a social democratic prime minister. Social democracy, if it is to mean anything, must surely be about doing its best to protect its citizens from the harsh winds of international capital and globalisation, to preserve personal sovereignty. This was a very different vision. It was a vision of an almost nihilistic politics. As we’ve seen, leftist governments all over the West were wrestling with the challenges of globalisation and the constraints that its associated processes implied, but Blair seemed to come to embrace that new order with zeal. That zeal led New Labour to accept and encourage high levels of migration (especially the immediate extension of free movement to the new EU accession countries of eastern Europe in 2004), without much thought to the reaction of its culturally conservative voters, the consequences of which would prove profound. Blair was not merely wearing the ‘golden straitjacket’ of the global economy, perhaps as any social democratic prime minister would have had to do or will yet again, but appearing to enjoy the fit that little bit too much. Tony Benn used to say that the most powerful letters in the English language were ‘TINA’, or ‘There is no alternative.’ It was one thing taking that from a Conservative prime minister, but hearing the remorseless market logic from a Labour one – and worse still a Labour premier who seemed to salivate at the thought – felt like a bitter pill.

Today, Blair is unrepentant. He maintains that he was right to be straightforward about the inevitability of globalisation, telling me:

‘I wasn’t zealous about globalisation the way you described it; I was saying it was a fact. I haven’t decided as a matter of policy that the world is changing in this way, it is changed in this way and it’s changing for reasons to do with technology, with trade and migration; things that no single government or country either can stop or will stop … I was aware of the potential for a populist backlash from early on. So the thing I find odd about today is that people accuse me of allowing populism to develop; yes, sure, they were developing when I was in power it’s true but I was dealing with them. Social democracy is shifting because the workplace has also been shifting – therefore many of the things that are happening today are the product of new coalitions in politics and new fragmentation of politics that has been going on for a long period of time. What we did very consciously was create a coalition that could see us through that process – why was it both before becoming leader and after, I obsessed about law and order? Some people thought it was some sort of fetish. But it was because I could see that for working people who we traditionally represented a mere economic message was not enough, we also had to be dealing with their problem with security and the changing nature of their communities because of migration. These were questions that we were actively working on and we should have been actively carrying on working on, but what happened after 2007 was a feeling that we went too far on that stuff, that we should actually pull back – whereas that was never the answer; the answer was to carry on; all of those issues were going to intensify.’