полная версия

полная версияCharles Darwin: His Life Told in an Autobiographical Chapter, and in a Selected Series of His Published Letters

Scattered through his letters are one or two references to pain or uneasiness felt in the region of the heart. How far these indicate that the heart was affected early in life, I cannot pretend to say; in any case it is certain that he had no serious or permanent trouble of this nature until shortly before his death. In spite of the general improvement in his health, which has been above alluded to, there was a certain loss of physical vigour occasionally apparent during the last few years of his life. This is illustrated by a sentence in a letter to his old friend Sir James Sulivan, written on January 10, 1879: "My scientific work tires me more than it used to do, but I have nothing else to do, and whether one is worn out a year or two sooner or later signifies but little."

A similar feeling is shown in a letter to Sir J. D. Hooker of June 15, 1881. My father was staying at Patterdale, and wrote: "I am rather despondent about myself… I have not the heart or strength to begin any investigation lasting years, which is the only thing I enjoy, and I have no little jobs which I can do."

In July, 1881, he wrote to Mr. Wallace: "We have just returned home after spending five weeks on Ullswater; the scenery is quite charming, but I cannot walk, and everything tires me, even seeing scenery… What I shall do with my few remaining years of life I can hardly tell. I have everything to make me happy and contented, but life has become very wearisome to me." He was, however, able to do a good deal of work, and that of a trying sort,294 during the autumn of 1881, but towards the end of the year, he was clearly in need of rest: and during the winter was in a lower condition than was usual with him.

On December 13, he went for a week to his daughter's house in Bryanston Street. During his stay in London he went to call on Mr. Romanes, and was seized when on the door-step with an attack apparently of the same kind as those which afterwards became so frequent. The rest of the incident, which I give in Mr. Romanes' words, is interesting too from a different point of view, as giving one more illustration of my father's scrupulous consideration for others: —

"I happened to be out, but my butler, observing that Mr. Darwin was ill, asked him to come in. He said he would prefer going home, and although the butler urged him to wait at least until a cab could be fetched, he said he would rather not give so much trouble. For the same reason he refused to allow the butler to accompany him. Accordingly he watched him walking with difficulty towards the direction in which cabs were to be met with, and saw that, when he had got about three hundred yards from the house, he staggered and caught hold of the park-railings as if to prevent himself from falling. The butler therefore hastened to his assistance, but after a few seconds saw him turn round with the evident purpose of retracing his steps to my house. However, after he had returned part of the way he seems to have felt better, for he again changed his mind, and proceeded to find a cab."

During the last week of February and in the beginning of March, attacks of pain in the region of the heart, with irregularity of the pulse, became frequent, coming on indeed nearly every afternoon. A seizure of this sort occurred about March 7, when he was walking alone at a short distance from the house; he got home with difficulty, and this was the last time that he was able to reach his favourite 'Sand-walk.' Shortly after this, his illness became obviously more serious and alarming, and he was seen by Sir Andrew Clark, whose treatment was continued by Dr. Norman Moore, of St. Bartholomew's Hospital, and Dr. Allfrey, at that time in practice at St. Mary Cray. He suffered from distressing sensations of exhaustion and faintness, and seemed to recognise with deep depression the fact that his working days were over. He gradually recovered from this condition, and became more cheerful and hopeful, as is shown in the following letter to Mr. Huxley, who was anxious that my father should have closer medical supervision than the existing arrangements allowed: —

"Down, March 27, 1882."My dear Huxley, – Your most kind letter has been a real cordial to me. I have felt better to-day than for three weeks, and have felt as yet no pain. Your plan seems an excellent one, and I will probably act upon it, unless I get very much better. Dr. Clark's kindness is unbounded to me, but he is too busy to come here. Once again, accept my cordial thanks, my dear old friend. I wish to God there were more automata295 in the world like you.

"Ever yours,"Ch. Darwin."The allusion to Sir Andrew Clark requires a word of explanation. Sir Andrew himself was ever ready to devote himself to my father, who however, could not endure the thought of sending for him, knowing how severely his great practice taxed his strength.

No especial change occurred during the beginning of April, but on Saturday 15th he was seized with giddiness while sitting at dinner in the evening, and fainted in an attempt to reach his sofa. On the 17th he was again better, and in my temporary absence recorded for me the progress of an experiment in which I was engaged. During the night of April 18th, about a quarter to twelve, he had a severe attack and passed into a faint, from which he was brought back to consciousness with great difficulty. He seemed to recognise the approach of death, and said, "I am not the least afraid to die." All the next morning he suffered from terrible nausea and faintness, and hardly rallied before the end came.

He died at about four o'clock on Wednesday, April 19th, 1882, in the 74th year of his age.

I close the record of my father's life with a few words of retrospect added to the manuscript of his Autobiography in 1879: —

"As for myself, I believe that I have acted rightly in steadily following and devoting my life to Science. I feel no remorse from having committed any great sin, but have often and often regretted that I have not done more direct good to my fellow creatures."

APPENDIX I.

THE FUNERAL IN WESTMINSTER ABBEY

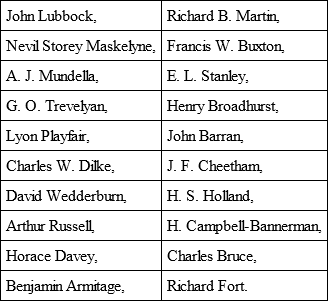

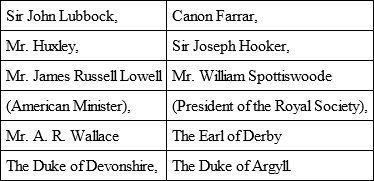

On the Friday succeeding my father's death, the following letter, signed by twenty Members of Parliament, was addressed to Dr. Bradley, Dean of Westminster: —

House of Commons, April 21, 1882.Very Rev. Sir, – We hope you will not think we are taking a liberty if we venture to suggest that it would be acceptable to a very large number of our fellow-countrymen of all classes and opinions that our illustrious countryman, Mr. Darwin, should be buried in Westminster Abbey.

We remain, your obedient servants,

The Dean was abroad at the time, and telegraphed his cordial acquiescence.

The family had desired that my father should be buried at Down: with regard to their wishes, Sir John Lubbock wrote: —

House of Commons, April 25, 1882.My dear Darwin, – I quite sympathise with your feeling, and personally I should greatly have preferred that your father should have rested in Down amongst us all. It is, I am sure, quite understood that the initiative was not taken by you. Still, from a national point of view, it is clearly right that he should be buried in the Abbey. I esteem it a great privilege to be allowed to accompany my dear master to the grave.

Believe me, yours most sincerely,

John Lubbock.W. E. Darwin, Esq.

The family gave up their first-formed plans, and the funeral took place in Westminster Abbey on April 26th. The pall-bearers were: —

The funeral was attended by the representatives of France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Russia, and by those of the Universities and learned Societies, as well as by large numbers of personal friends and distinguished men.

The grave is in the north aisle of the Nave, close to the angle of the choir-screen, and a few feet from the grave of Sir Isaac Newton. The stone bears the inscription —

CHARLES ROBERT DARWINBorn 12 February, 1809Died 19 April, 1882APPENDIX II

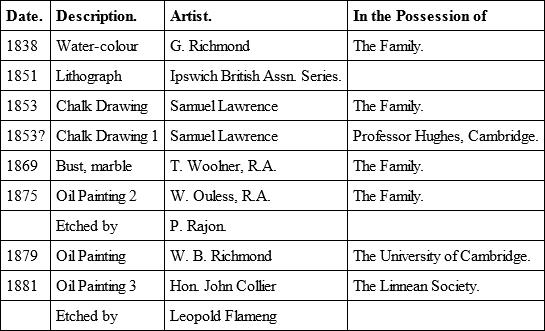

Portraits.

1. Probably a sketch made at one of the sittings for the last-mentioned.

2. A replica by the artist is in the possession of Christ's College, Cambridge.

3. A replica by the artist is in the possession of W. E. Darwin, Esq., Southampton.

Chief Portraits and Memorials not taken from Life.

1. A cast from this work is now placed in the New Museums at Cambridge.

Chief Engravings from Photographs

*1854? By Messrs. Maull and Fox, engraved on wood for Harper's Magazine (Oct. 1884). Frontispiece, Life and Letters, vol. i.

1868 By the late Mrs. Cameron, reproduced in heliogravure by the Cambridge Engraving Company for the present work.

*1870? By O. J. Rejlander, engraved on Steel by C. H. Jeens for Nature (June 4, 1874).

*1874? By Major Darwin, engraved on wood for the Century Magazine (Jan. 1883). Frontispiece, Life and Letters, vol. ii.

1881 By Messrs. Elliot and Fry, engraved on wood by G. Kruells, for vol. iii. of the Life and Letters.

*The dates of these photographs must, from various causes, remain uncertain. Owing to a loss of books by fire, Messrs. Maull and Fox can give only an approximate date. Mr. Rejlander died some years ago, and his business was broken up. My brother, Major Darwin, has no record of the date at which his photograph was taken.

1

I have not thought it necessary to indicate all the omissions in the abbreviated letters.

2

See Charles Darwin's biographical sketch of his grandfather, prefixed to Ernst Krause's Erasmus Darwin. (Translated from the German by W. S. Dallas, 1878.) Also Miss Meteyard's Life of Josiah Wedgwood.

3

The above passage is, by permission of Messrs. Smith & Elder, taken from my article Charles Darwin, in the Dictionary of National Biography.

4

A Group of Englishmen, by Miss Meteyard, 1871.

5

The late Mr. Hensleigh Wedgwood's house in Surrey.

6

Kept by Rev. G. Case, minister of the Unitarian Chapel in the High Street. Mrs. Darwin was a Unitarian and attended Mr. Case's chapel, and my father as a little boy went there with his elder sisters. But both he and his brother were christened and intended to belong to the Church of England; and after his early boyhood he seems usually to have gone to church and not to Mr. Case's. It appears (St. James's Gazette, December 15, 1883) that a mural tablet has been erected to his memory in the chapel, which is now known as the "Free Christian Church." – F. D.

7

Rev. W. A. Leighton remembers his bringing a flower to school and saying that his mother had taught him how by looking at the inside of the blossom the name of the plant could be discovered. Mr. Leighton goes on, "This greatly roused my attention and curiosity, and I inquired of him repeatedly how this could be done?" – but his lesson was naturally enough not transmissible. – F. D.

8

His father wisely treated this tendency not by making crimes of the fibs, but by making light of the discoveries. – F. D.

9

The house of his uncle, Josiah Wedgwood, the younger.

10

It is curious that another Shrewsbury boy should have been impressed by this military funeral; Mr. Gretton, in his Memory's Harkback, says that the scene is so strongly impressed on his mind that he could "walk straight to the spot in St. Chad's churchyard where the poor fellow was buried." The soldier was an Inniskilling Dragoon, and the officer in command had been recently wounded at Waterloo, where his corps did good service against the French Cuirassiers.

11

He lodged at Mrs. Mackay's, 11, Lothian Street. What little the records of Edinburgh University can reveal has been published in the Edinburgh Weekly Dispatch, May 22, 1888; and in the St. James's Gazette, February 16, 1888. From the latter journal it appears that he and his brother Erasmus made more use of the library than was usual among the students of their time.

12

I have heard him call to mind the pride he felt at the results of the successful treatment of a whole family with tartar emetic. – F. D.

13

Dr. Coldstream died September 17, 1863; see Crown 16mo. Book Tract. No. 19 of the Religious Tract Society (no date).

14

The society was founded in 1823, and expired about 1848 (Edinburgh Weekly Dispatch, May 22, 1888).

15

Josiah Wedgwood, the son of the founder of the Etruria Works.

16

Justum et tenacem propositi virumNon civium ardor prava jubentium,Non vultus instantis tyranniMente quatit solida.17

Tenth in the list of January 1831.

18

I gather from some of my father's contemporaries that he has exaggerated the Bacchanalian nature of those parties. – F. D.

19

Rev. C. Whitley, Hon. Canon of Durham, formerly Reader in Natural Philosophy in Durham University.

20

The late John Maurice Herbert, County Court Judge of Cardiff and the Monmouth Circuit.

21

Afterwards Sir H. Thompson, first baronet.

22

The Cambridge Ray Club, which in 1887 attained its fiftieth anniversary, is the direct descendant of these meetings, having been founded to fill the blank caused by the discontinuance, in 1836, of Henslow's Friday evenings. See Professor Babington's pamphlet, The Cambridge Ray Club, 1887.

23

Mr. Jenyns (now Blomefield) described the fish for the Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle; and is author of a long series of papers, chiefly Zoological. In 1887 he printed, for private circulation, an autobiographical sketch, Chapters in my Life, and subsequently some (undated) addenda. The well-known Soame Jenyns was cousin to Mr. Jenyns' father.

24

In connection with this tour my father used to tell a story about Sedgwick: they had started from their inn one morning, and had walked a mile or two, when Sedgwick suddenly stopped, and vowed that he would return, being certain "that damned scoundrel" (the waiter) had not given the chambermaid the sixpence intrusted to him for the purpose. He was ultimately persuaded to give up the project, seeing that there was no reason for suspecting the waiter of perfidy. – F. D.

25

Philosophical Magazine, 1842.

26

Josiah Wedgwood.

27

The Count d'Albanie's claim to Royal descent has been shown to be baaed on a myth. See the Quarterly Review, 1847, vol. lxxxi. p. 83; also Hayward's Biographical and Critical Essays, 1873, vol. ii. p. 201.

28

Read at the meeting held November 16, 1835, and printed in a pamphlet of 31 pp. for distribution among the members of the Society.

29

In Fitzwilliam Street.

30

Geolog. Soc. Proc. ii. 1838, pp. 416-449.

31

1839, pp. 39-82.

32

Geolog. Soc. Proc. iii. 1842.

33

Geolog. Trans. v. 1840.

34

Geolog. Soc. Proc. ii. 1838.

35

Philosophical Magazine, 1842.

36

The slight repetition here observable is accounted for by the notes on Lyell, &c., having been added in April, 1881, a few years after the rest of the Recollections were written. – F. D.

37

A passage referring to X. is here omitted. – F. D.

38

Geological Observations, 2nd Edit. 1876. Coral Reefs, 2nd Edit. 1874

39

Published by the Ray Society.

40

Miss Bird is mistaken, as I learn from Professor Mitsukuri. – F. D.

41

Geolog. Survey Mem., 1846.

42

Between November 1881 and February 1884, 8500 copies were sold. – F. D.

43

The falseness of the published statements on which Mr. Huth relied were pointed out in a slip inserted in all the unsold copies of his book, The Marriage of near Kin. – F. D.

44

As an exception, may be mentioned, a few words of concurrence with Dr. Abbott's Truths for the Times, which my father allowed to be published in the Index.

45

Addressed to Mr. J. Fordyce, and published by him in his Aspects of Scepticism, 1883.

46

October 1836 to January 1839.

47

My father asks whether we are to believe that the forms are preordained of the broken fragments of rock which are fitted together by man to build his houses. If not, why should we believe that the variations of domestic animals or plants are preordained for the sake of the breeder? "But if we give up the principle in one case, … no shadow of reason can be assigned for the belief that variations alike in nature and the result of the same general laws, which have been the groundwork through natural selection of the formation of the most perfectly adapted animals in the world, man included, were intentionally and specially guided." —Variation of Animals and Plants, 1st Edit. vol. ii. p. 431. – F. D.

48

The Origin of Species.

49

Dr. Gray's rain-drop metaphor occurs in the Essay, Darwin and his Reviewers (Darwiniana, p. 157): "The whole animate life of a country depends absolutely upon the vegetation, the vegetation upon the rain. The moisture is furnished by the ocean, is raised by the sun's heat from the ocean's surface, and is wafted inland by the winds. But what multitudes of rain-drops fall back into the ocean – are as much without a final cause as the incipient varieties which come to nothing! Does it therefore follow that the rains which are bestowed upon the soil with such rule and average regularity were not designed to support vegetable and animal life?"

50

The Duke of Argyll (Good Words, April 1885, p. 244) has recorded a few words on this subject, spoken by my father in the last year of his life. " … in the course of that conversation I said to Mr. Darwin, with reference to some of his own remarkable works on the Fertilisation of Orchids, and upon The Earthworms, and various other observations he made of the wonderful contrivances for certain purposes in nature – I said it was impossible to look at these without seeing that they were the effect and the expression of mind. I shall never forget Mr. Darwin's answer. He looked at me very hard and said, 'Well, that often comes over me with overwhelming force; but at other times,' and he shook his head vaguely, adding, 'it seems to go away.'"

51

Dr. Aveling has published an account of a conversation with my father. I think that the readers of this pamphlet (The Religious Views of Charles Darwin, Free Thought Publishing Company, 1883) may be misled into seeing more resemblance than really existed between the positions of my father and Dr. Aveling: and I say this in spite of my conviction that Dr. Aveling gives quite fairly his impressions of my father's views. Dr. Aveling tried to show that the terms "Agnostic" and "Atheist" are practically equivalent – that an atheist is one who, without denying the existence of God, is without God, inasmuch as he is unconvinced of the existence of a Deity. My father's replies implied his preference for the unaggressive attitude of an Agnostic. Dr. Aveling seems (p. 5) to regard the absence of aggressiveness in my father's views as distinguishing them in an unessential manner from his own. But, in my judgment, it is precisely differences of this kind which distinguish him so completely from the class of thinkers to which Dr. Aveling belongs.

52

The figure in Insectivorous Plants representing the aggregated cell-contents was drawn by him.

53

Life and Letters, vol. iii. frontispiece.

54

The basket in which she usually lay curled up near the fire in his study is faithfully represented in Mr. Parson's drawing given at the head of the chapter.

55

Cf. Leslie Stephen's Swift, 1882, p. 200, where Swift's inspection of the manners and customs of servants are compared to my father's observations on worms, "The difference is," says Mr. Stephen, "that Darwin had none but kindly feelings for worms."

56

The words, "A good and dear child," form the descriptive part of the inscription on her gravestone. See the Athenæum, Nov. 26, 1887.

57

Some pleasant recollections of my father's life at Down, written by our friend and former neighbour, Mrs. Wallis Nash, have been published in the Overland Monthly (San Francisco), October 1890.

58

Darwin considéré au point de vue des causes de son succès (Geneva, 1882).

59

My father related a Johnsonian answer of Erasmus Darwin's: "Don't you find it very inconvenient stammering, Dr. Darwin?" "No, Sir, because I have time to think before I speak, and don't ask impertinent questions."

60

This is not so much an example of superabundant theorising from a small cause as of his wish to test the most improbable ideas.

61

That is to say, the sexual relations in such plants as the cowslip.

62

The racks in which the portfolios were placed are shown in the illustration at the head of the chapter, in the recess at the right-hand side of the fire-place.

63

He departed from his rule in his "Note on the Habits of the Pampas Woodpecker, Colaptes campestris," Proc. Zool. Soc., 1870, p. 705: also in a letter published in the Athenæum (1863, p. 554), in which case he afterwards regretted that he had not remained silent. His replies to criticisms, in the latter editions of the Origin, can hardly be classed as infractions of his rule.

64

"On Tuesday last Charles Darwin, of Christ's College, was admitted B.A." —Cambridge Chronicle, Friday, April 29th, 1831.

65

Readers of Calverley (another Christ's man) will remember his tobacco poem ending "Hero's to thee, Bacon."

66

The rooms are on the first floor, on the west side of the middle staircase. A medallion (given by my brother) has recently been let into the wall of the sitting-room.

67

For instance in a letter to Hooker (1817): – "Many thanks for your welcome note from Cambridge, and I am glad you like my Alma Mater, which I despise heartily as a place of education, but love from many most pleasant recollections."