полная версия

полная версияOmphalos: An Attempt to Untie the Geological Knot

These, however, were not the massive colossi that browse in the African or Indian jungles of our days; no Elephant, no Rhinoceros, no Hippopotamus was as yet formed. But several kinds of Tapir wallowed in the morasses; and a goodly number of largish beasts, whose affinities were with the Pachydermata, while their analogies were with the Ruminantia, served as substitutes for the latter order, which was wholly wanting. These interesting quadrupeds, forming the genus Anoplotherium, were remarkable for two peculiarities, – their feet were two-toed, and their teeth were ranged in a continuous series, without any interval between the incisors and the molars. They varied in size from that of an ass to that of a hare.

The physical conditions of our earth, when it was tenanted by these creatures, is thus described: – "All the great plains of Europe, and the districts through which the principal rivers now run, were then submerged; in all probability, the land chiefly extended in a westerly direction, far out into the Atlantic, possibly trending to the south, and connecting the western shores of England with the volcanic islands off the west coast of Africa. The great mountain chains of Europe, the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Apennines, the mountains of Greece, the mountains of Bohemia, and the Carpathians, existed then only as chains of islands in an open sea. Elevatory movements, having an east and west direction, had, however, already commenced, and were producing important results, laying bare the Wealden district in the south-east of England. The southern and central European district, and parts of western Asia, were the recipients of calcareous deposits (chiefly the skeletons of Foraminifera), forming the Apennine limestone; while numerous islands were gradually lifted above the sea, and fragments of disturbed and fractured rock were washed upon the neighbouring shallows or coast-lines, forming beds of gravel covering the Chalk. The beds of Nummulites and Miliolites, contemporaneous with those containing the Sheppey plants and the Paris quadrupeds, seem to indicate a deep sea at no great distance from shore, and render it probable that there were frequent alternations of elevation and depression, perhaps the result of disturbances acting in the direction already alluded to.

"The shores of the islands and main land were, however, occasionally low and swampy, rivers bringing down mud in what is now the south-east of England, and the neighbourhood of Brussels, but depositing extensive calcareous beds near Paris. Deep inlets of the sea, estuaries, and the shifting mouths of a river, were also affected by numerous alterations of level not sufficient to destroy, but powerful enough to modify, the animal and vegetable species then existing; and these movements were continued for a long time."35

After the elevation of the mountain summits of Europe above the sea, and while the same causes were still in operation, deposits were being made in the narrow intervening seas of the Archipelago, such as the present south of France, the valleys of the Rhine and Danube, the eastern districts of England and Portugal. These deposits were partly marine and partly lacustrine; the former consisting largely of loose sands, mingled with shells and gravel. In Switzerland is a thick mass of conglomerate; and in the district around Mayence, there is a series of fresh-water limestones, and sandstones charged with organic remains.

The changes which took place during this comparatively recent epoch were not sudden, but gradual; the results of operations which were probably going on without intermission, and perhaps have not yet ceased. The land was more and more upheaved, till at length, what had been an archipelago of islands became a continent, and Europe assumed the form which it bears on our maps.

The most interesting addition to the natural history of the Miocene, or Middle Tertiary period, was the Dinotherium– a huge Pachyderm, twice as large as an elephant, with a tapir-like proboscis, and two great tusks curving downward from the lower jaw. It was, doubtless, aquatic in its habits, and possibly (for its hinder parts are not known), it may have been allied to the Dugong and Manatee, those whale-like Pachyderms, with a broad horizontal tail, instead of posterior limbs.

Other great herbivorous beasts roamed over the new-made land. The Mastodons, closely allied to the Elephant, had their head-quarters in North America, but extended also to Europe. And the Elephants themselves, of several species, were spread over the northern hemisphere, even to the polar regions. The Hippopotamus, the Rhinoceros, and other creatures, now exclusively tropical, were also inhabitants of the same northern latitudes.

From some specimens of Elephants and Rhinoceroses of this period, which seem to have been buried in avalanches, and thus to have been preserved from decomposition, even of the more transitory parts, as muscle and skin, we learn something of the climate that prevailed. The very fact of their preservation, by the antiseptic power of frost, shows that it was not a tropical climate in which they lived; and the clothing of thick wool, fur, and hair, which protected the skin of the Mammoth, or Siberian Elephant, tends to the same conclusion. At the same time, those regions were not so intensely cold as they are now. For the district in which the remains of Elephants and their associates are found, in almost incredible abundance, is that inhospitable coast of northern Asia which bounds the Polar Sea.

The trees of a temperate climate – the oak, the beech, the maple, the poplar, and the birch – which now attain their highest limit somewhere about 70° of north latitude, and there are dwarfed to minute shrubs, appear then to have grown at the very verge of the polar basin; and that in the condition of vast and luxuriant forests, perhaps occupying sheltered valleys between mountains whose steep sides were covered with snow, already become perennial, and ever and anon rolling down in overwhelming avalanches, such as those which now occasionally descend into the valleys of the Swiss Alps.

The coast of Suffolk displays a formation known as the Crag – a local name for gravel – which rests partly on the chalk; but, as it lies in other parts over the London Clay, it is assigned to the later Tertiary, or what is called the Pleiocene period. It is divided into the coralline and the red crag, the latter being uppermost where they exist together, and therefore being the more recent. The Coralline Crag is nearly composed of corals and shells, the former almost wholly extinct now; but the latter containing upwards of seventy species still existing in the adjacent seas. The Red Crag contains few zoophytes, but is remarkable for the remains of at least five species of Whales. Other Mammalia occur in this formation, among which are the red deer and the wild boar of modern Europe.

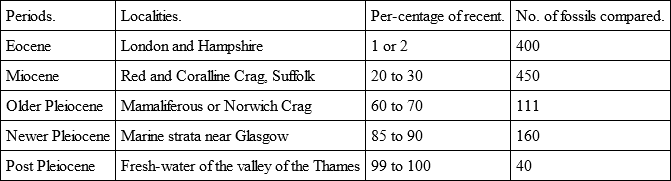

The gradual but rapid approximation of the Tertiary fauna to that of the present surface is well indicated by Mr. Lyell's table (1841) of recent and fossil species in the English formations: —

It is to this period that are assigned the animals whose bones are found in astonishing numbers in limestone caverns, as, for example, that notable one at Kirkdale, in Yorkshire, which was examined by Professor Buckland.

This is a cave in the Oolitic limestone, with a nearly level floor, which was covered with a deposit of mud, on which an irregular layer of sparry stalagmite had formed by the dripping of water from the low roof, carrying lime in solution. Beneath this crust the remains were found.

Of the animals to which the bones belonged, six were Carnivora, viz. hyæna, felis, bear, wolf, fox, weasel; four Pachydermata, viz. elephant, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, horse; four Ruminantia, viz. ox, and three species of deer; four Rodentia, viz. hare, rabbit, water-rat, mouse; five Birds, viz. raven, pigeon, lark, duck, snipe.

The bones were almost universally broken; the fragments exhibited no marks of rolling in the water, but a few were corroded; some were worn and polished on the convex surface; many indented, as by the canine teeth of carnivorous animals. In the cave the peculiar excrement of hyænas (album græcum) was common; the remains of these predacious beasts were the most abundant of all the bones; their teeth were found in every condition, from the milk-tooth to the old worn stump; and from the whole evidence Dr. Buckland adopted the conclusion, in which almost every subsequent writer has acquiesced, that Kirkdale Cave was a den of hyænas during the period when elephants and hippopotami (not of existing species) lived in the northern regions of the globe, and that they dragged into it for food the bodies of animals which frequented the vicinity.36

Thus in these spots we find, observes Professor Ansted, "written in no obscure language, a portion of the early history of our island after it had acquired its present form, while it was clothed with vegetation, and when its plains and forests were peopled by many of the species which still exist there; but when there also dwelt upon it large carnivorous animals, prowling about the forests by night, and retiring by day to these natural dens."

In our own country, and in many other parts of the world, we find fragments of stone distributed over the surface, sometimes in the form of enormous blocks, bearing in their fresh angles evidence that they have been little disturbed since their disruption, but sometimes much rubbed and worn, and broken into smaller pieces, till they form what is known as gravel. In many cases the original rock from which these masses have been separated does not exist in the vicinity of their locality; and it is not till we reach a distance, often of hundreds of miles, that we find the formation of which they are a component part.

Various causes have been suggested for the transport of these erratic blocks, of which the most satisfactory is the agency of ice, either as slow-moving glaciers, or as oceanic icebergs.

"The common form of a glacier," says Professor J. Forbes, "is a river of ice filling a valley, and pouring down its mass into other valleys yet lower. It is not a frozen ocean, but a frozen torrent. Its origin or fountain is in the ramifications of the higher valleys and gorges, which descend amongst the mountains perpetually snow-clad. But what gives to a glacier its most peculiar and characteristic feature is, that it does not belong exclusively or necessarily to the snowy region already mentioned. The snow disappears from its surface in summer as regularly as from that of the rocks which sustain its mass. It is the prolongation or outlet of the winter-world above; its gelid mass is protruded into the midst of warm and pine-clad slopes and green-sward, and sometimes reaches even to the borders of cultivation."37

The glacier moves onward with a slow but steady march towards the mouth of its valley. Its lowest stratum carries with it numerous fragments of rock, which, pressed by the weight of the mighty mass, scratch and indent the surfaces over which they move, and sometimes polish them. These marks are seen on many rock-surfaces now exposed, and they are difficult to explain on any other hypothesis than that of glacial action.

But the alternate influence of summer and winter – the percolation of rain into the mountain fissures, and the expansion of freezing – dislodge great angular fragments of rock, which fall on the glacier beneath. Slowly but surely these then ride away towards the mouth of the valley, till they reach a point where the warmth of the climate does not permit the ice to proceed; the blocks then are deposited as the mass melts. But if the climate itself were elevated, or if the surface were lowered so as to immerse the glacier in the sea, it would melt throughout its course, and then the blocks would be found arranged in long lines or moraines, such as we see now in many places.

If the glacier-valley debouch on the sea, the ice gradually projects more and more, until the motions of the waves break off a great mass, which floats away, carrying on its surface the accumulation of boulders, gravel, and other débris which it had acquired during its formation. It is now an iceberg, which, carried by the southern currents, approaches a warmer climate, melts, and deposits its cargo, perhaps hundreds of leagues from the valley where it was shipped, and as fresh as when its component frusta were detached from the primitive rock.

If the abundance of such erratic blocks and foreign gravel seem to require a greater amount of glacial action than is now extant, it has been suggested that the volcanic energy which elevated Europe may have been succeeded by a measure of subsidence before the land attained its present permanent condition. Hence there may have been, during the Tertiary epoch, mountain chains of great elevation, sufficient to supply the glaciers, which, on their subsidence, melted on the spot where they were submerged, or floated away as icebergs on the pelagic currents, till they grounded on the bays and inlets of other shores, which were subsequently elevated again.

Thus a large portion of the animals which then inhabited these islands (up to that time, perhaps, united to the continent) would be drowned, and many species quite obliterated, a few alone remaining to connect our present fauna with that of the submerged area, when the land rose again to its existent state.

It would not materially augment the force of the evidence already adduced on the question of chronology, to examine in detail the fossil remains of South America, Australia, and New Zealand. The gigantic Sloths38 of the first, the gigantic Marsupials of the second, and the gigantic Birds of the third, however interesting individually, and especially as showing that a prevailing type governed the fauna in each locality then as now – are all formations of the Tertiary period, and some of them, at least, seem to have run on even into the present epoch. Indeed, it is not quite certain that the enormous birds of New Zealand and Madagascar are even yet extinct.

The phenomenon of raised sea-beaches is one of great interest, and seems to be connected with the alternate elevations and depressions of the Tertiary epoch, perhaps marking the successive steps of the upheaval of the land. In several parts of England the coast-line exhibits one or more shelves parallel with the existing sea-beach, and covered with similar shingle, sand, and sea-shells. And the same phenomenon is exhibited on a still more gigantic scale in South America. Mr. Darwin39 found that for a distance of at least 1,200 miles from the Rio de la Plata to the Straits of Magellan on the eastern side, and for a still longer distance on the west, the coast-line and the interior have been raised to a height of not less than 100 feet in the northern part, but as much as 400 feet in Patagonia. All this change has taken place within a comparatively short period; for in Valparaiso, where the effect is most considerable, modern marine deposits, with human remains, are seen at the height of 1,300 feet above the sea.

At what exact point, geologically, the period of human history begins, it is impossible to say. No evidence of Man's presence has occurred older than the latest Tertiary deposits, which insensibly merge into the Alluvial. It seems certain that human remains have been found in chronological association with those of animals long extinct, and there appears no reason to doubt that some species of animals, as the Irish Deer, the Moa of New Zealand, and the Dodo of the Mauritius, have disappeared from creation within a period of a few centuries.40 It is not improbable that the last of the Moho race may have lived only long enough to grace the pages of the "Birds of Australia."

It is as important as it is interesting, to observe that the same kinds of physical operations have been, within the present epoch, and are still, going on, as those whose results are chronicled in the rocks. Strata of alluvium are constantly being formed on a scale which, though it does not suddenly affect the outline of coasts, and therefore appears small, yet is great in reality.

The Ganges is estimated to pour into the Indian Ocean nearly 6,400 millions of tons of mud every year; and its delta is a triangle whose sides are two hundred miles long. The delta of the Mississippi is of about the same size, and it advances steadily into the Gulf of Mexico at the rate of a mile in a century.

The accumulation of river-mud is gradually filling up the Adriatic Sea. From the northernmost point of the Gulf of Trieste to the south of Ravenna, there is an uninterrupted series of recent accessions of land, more than a hundred miles in length, which, within the last twenty centuries, have increased from two to twenty miles in breadth.

The coral-polypes are working still with great energy. Mr. Darwin mentions two or three examples of the rate of increase, one of which only I shall cite. In the lagoon of Keeling Atoll, a channel was dug for the passage of a schooner built upon the island, through the reef into the sea; in ten years afterward, when it was examined, it was found almost choked up with living coral.

Volcanic action is busy in many parts of the earth, pouring forth clouds of ashes and torrents of molten rock; and instances are not wanting in which new islands have been raised from the bed of the ocean by this means, within the sphere of history.

Slow and permanent changes of level are still being produced on the earth's crust. The bottom of the Baltic has been, for several centuries at least, in process of continuous elevation, the effects of which are palpable. Many rocks formerly covered are now permanently exposed; channels between islets, formerly used, are now closed up, and beds of marine shells have become bare. On the other hand, the whole area of the Pacific Polynesia seems subsiding.

Deposits are being made by waters which hold earthy substances in solution. The principal of these is lime. Several remarkable examples of this kind are quoted by Sir Charles Lyell, in one of which there is a thickness of 200 or 300 feet of travertine of recent deposit, while in another a solid mass thirty feet thick was deposited in about twenty years. He also states that there are other countless places in Italy where the constant formation of limestone may be seen, while the same may be said of Auvergne and other volcanic districts. In the Azores, Iceland, and elsewhere, silica is deposited often to a considerable extent. Deposits of asphalt and other bituminous products occur in other places.41

The floors of limestone caverns are frequently strewn with fossil bones, which are imbedded in stalagmite, and this incrustation is still in progress of formation. It is remarkable that in this deposit alone we obtain the bones of Man in a fossil condition. The two creations, – the extinct and the extant, – or rather the prochronic and the diachronic – here unite. But there is no line of demarcation between them; they merge insensibly into each other. The bones of Man, and even his implements and fragments of pottery, are found mingled with the skeletons of extinct animals in the caves of Devonshire, in those of Brazil,42 and in those of Franconia. In Peru, some scores of human skeletons have been found in a bed of travertine, associated with marine shells; the stratum itself being covered by a deep layer of vegetable soil, forming the face of a hill crowned with large trees.

From a very interesting paper by M. Marcel de Serres, it appears indubitable that the existing shells of the Mediterranean are even now passing in numbers into the fossil state, and that not in quiet spots only, but where the sea is subject to violent agitations. Specimens of common species, "completely petrified, have been converted into carbonate of lime at the same time that they have lost the animal matter which they originally contained. Their hardness and solidity are greater than those of some petrified species from tertiary formations."

"In the collection of M. Doumet, Mayor of Cette, there exists an anchor which exhibits the same circumstances, and which is also covered with a layer of solid calcareous matter. This contains specimens of Pecten, Cardium, and Ostrea, completely petrified, and the hardness of which is equal to that of fossil species from secondary formations. On the surface of the deposit in which the anchor is imbedded, there are Anomiæ and Serpulæ, which were living when the anchor was got out of the sea; these present no trace of alteration."43

Thus we have brought down the record to an era embraced by human history, and even to individual experience; and we confidently ask, Is it possible, is it imaginable, that the whole of the phenomena which occur below the diluvial deposits can have been produced within six days, or seventeen centuries? Let us recapitulate the principal facts.

1. The crust of the earth is composed of many layers, placed one on another in regular order. All of these are solid, and most are of great density and hardness. Most of them are of vast thickness, the aggregate not being less than from seven to ten miles.

2. The earlier of these were made and consolidated before the newer were formed; for in several cases, it is demonstrable that the latter were made out of the débris of the former. Thus the compact and hard granite was disintegrated grain by grain; the component granules were rolled awhile in the sea till their angles were rubbed down; they were slowly deposited, and then consolidated in layers.

3. A similar process goes on again and again to form other strata, all occupying long time, and all presupposing the earlier ones.44

4. After some strata have been formed and solidified, convulsions force them upward, contort them, break them, split them asunder. Melted matter is driven through the outlets, fills the veins, spreads over the surface, settles into the hollows, cools and solidifies.

5. After the outflowing and consolidation of these volcanic streams, the action of running water cuts them down, cleaving beds of immense depth through their substance. Mr. Poulett Scrope, speaking of the solidified streams of basalt, in the volcanic district of Southern France, observes: —

"These ancient currents have since been corroded by rivers, which have worn through a mass of 150 feet in height, and formed a channel even in the granite rocks beneath, since the lava first flowed into the valley. In another spot, a bed of basalt, 160 feet high, has been cut through by a mountain stream. The vast excavations effected by the erosive power of currents along the valleys which feed the Ardèche, since their invasion by lava-currents, prove that even the most recent of these volcanic eruptions belong to an era incalculably remote."45

6. A series of organic beings appears, lives, generates, dies; lives, generates, dies; for thousands and thousands of successive generations. Tiny polypes gradually build up gigantic masses of coral, – mountains and reefs – microscopic foraminifera accumulate strata of calcareous sand; still more minute infusoria – forty millions to the inch – make slates, many yards thick, of their shells alone.

7. The species at length die out – a process which we have no data to measure,46 though we may reasonably conclude it very long. Sometimes the whole existing fauna seems to have come to a sudden violent end; at others, the species die out one by one. In the former case suddenly, in the latter progressively, new creatures supply the place of the old. Not only do species change; the very genera change, and change again. Forms of beings, strange beings, beings of uncouth shape, of mighty ferocity and power, of gigantic dimensions, come in, run their specific race, propagate their kinds generation after generation, – and at length die out and disappear; to be replaced by other species, each approaching nearer and nearer to familiar forms.

8. Though these early creatures were unparalleled by anything existing now, yet they were animals of like structure and economy essentially. We can determine their analogies and affinities; appoint them their proper places in the orderly plan of nature, and show how beautifully they fill hiatuses therein. They had shells, crusts, plates, bones, horns, teeth, exactly corresponding in structure and function to those of recent animals. In some cases we find the young with its milk-teeth by the side of its dam with well-worn grinders. The fossil excrement is seen not only dropped, but even in the alimentary canal. Bones bear the marks of gnawing teeth that dragged them and cracked them, and fed upon them. The foot-prints of birds and frogs, of crabs and worms, are imprinted in the soil, like the faithful impression of a seal.47