полная версия

полная версияOmphalos: An Attempt to Untie the Geological Knot

The mention of the celestial orbs suggests to remembrance the famous argument for the vast antiquity of the material universe, founded on the time which is required for the propulsion of light. I believe it owes its origin to Sir William Herschel.

Speaking of the known velocity of light in connexion with the immense distance of certain nebulæ, that eminent astronomer made these remarks: —

"Hence it follows, that, when we… see an object of the calculated distance at which one of these very remote nebulæ may still be perceived… the rays of light which convey its image to the eye must have been more than nineteen hundred and ten thousand, that is, almost two millions, of years on their way; and that, consequently, so many years ago, this object must already have had an existence in the sidereal heavens, in order to send out those rays by which we now perceive it."107

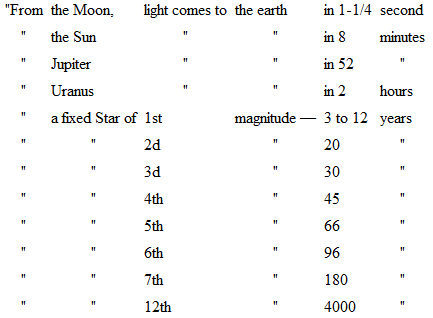

The notion has been amplified, with some interesting details, by a writer in the Scottish Congregational Magazine for January 1847; who thus throws the statements into a tabular form, and comments on them.

"Now, as we see objects by the rays of light passing from those objects to our eye, it follows that we do not perceive the heavenly bodies, as they are at the moment of our seeing them, but as they were at the time the rays of light by which we see them left those bodies. Thus when we look at the moon, we see her, not as she is at the moment of our beholding her disc, but as she was a second and a quarter before; for instance, we see her not at the moment of her rising above the horizon, but 1-1/4 second after she has risen. The sun also when he appears to us to have just passed the meridian, has already passed it by 8 minutes. So, in like manner, of the planets and the fixed stars. We see Jupiter, not as he is at the moment of our catching a sight of him, but as he was 52 minutes before. Uranus appears to us, not as he is at the moment of our discovering him, but as he was 2 hours previously. And a star of the 12th magnitude presents itself to our eye as it was 4,000 years ago: so that, suppose such a star to have been annihilated 3,000 years back, it would still be visible on the earth's surface for 1,000 years to come: or, suppose a star of the same magnitude had been created at the time the Israelites left Egypt, it will not be perceptible on the earth for nearly 700 years from this date."

Beautiful, and at first sight unanswerable as this argument is, it falls to the ground before the spear-touch of our Ithuriel, the doctrine of prochronism. There is nothing more improbable in the notion that the sensible undulation was created at the observer's eye, with all the pre-requisite undulations prochronic, than in the notion that blood was created in the capillaries of the first human body. The latter we have seen to be a fact: is the former an impossibility?

It may perhaps be said: – "The traces of prochronism you have adduced in created organisms may be granted, because they are inseparable from the presumed condition of those organisms respectively. The blood in the vessels, the hair, the teeth, the nails, may afford evidences of past processes; but then those are only past stages of what yet exists. The case, however, is not parallel with the fossil skeletons, many of which have no connexion with anything now existing. The concentric rings of a timber-tree are essential to its adult state; but how is the existence of the Pterodactyle or the Megatherium essential to that of the recent Draco volans, or the South American Sloth? Can you show in the new-formed creature any trace of some organ which does not come into its present condition of being, – of something which has quite passed away?"

Perhaps I can. The very concentric rings of the tree are considered by botanists as, in some sense, dead. The paradoxical dictum of Schleiden, – "No tree has leaves,"108– is grounded on this circumstance, that the woody portion of the mass is the inert result of former generations, and that the present race of leaves is growing, not out of the woody portion of the tree, but out of its herbaceous extremities, "which grow upon the woody stem as upon a ground, formed by the process of vegetation. This common ground, namely, the woody stem, which is almost lifeless in comparison with the herbaceous parts engaged in active growth, is annually covered with a vigorous sheath under the protecting bark; and this sheath is the ground of the nourishment of all the vegetating herbaceous extremities."109

The polygonal plates into which the bark of the Testudinaria divides, not only show many superposed laminæ, at any given moment of its adult condition, but also bear witness, in the broad existent surface of each one, to former laminæ, yet older than the oldest now present, which have disintegrated and dropped off.

The Palm and the Tree-fern show, in their trunk-scars, evidences of organs which have completely died away and disappeared; while, between these scars and the generation of living fronds, there is, at any given moment of the tree's history, a series of fronds which are quite dead and dry, but which have not yet disappeared.

The Nerita, a genus of beautiful shells from the tropical seas, dissolves away and removes, in the progress of growth, the spiral column, which originally formed the axis of development; so that, in adult age, the spiral direction of the whole testifies to the past existence of a column which has quite disappeared.

In that species of Murex,110 which, on account of the long and slender rostellum, and the spines with which it is covered, is known to collectors as the Thorny Woodcock (M. tenuispina), the shelly spines of the earlier whorls would interfere with such as came, in process of development, to be superposed on them; for they cross the area which is to be the cavity enclosed by the advancing lip. They are, however, removed by absorption; but not so completely but that traces may still be discovered where they formerly existed: evidences of the quondam existence of what exists no longer.

Towards one side of the upper surface of the pretty Star-fish, Cribella rosea, (as in many other species of Star-fishes,) there is a curious little mark, known as the madreporic plate, the use of which has greatly puzzled naturalists. Sars, the Norwegian zoologist, has unveiled the mystery.111 The young larva, before it assumes the stellar form, is furnished with a sort of thick column, divided into four diverging clubbed arms, which are adhering organs, ancillary to locomotion. In the process of development, however, new locomotive organs are formed; and this four-fold column, being no longer needed, sloughs away; and that so completely, that not a trace of its existence remains, except this scar, or "madreporic plate;" which is therefore a permanent record of something that has quite passed away.

But the closest parallel to the relation borne by the skeleton of an extinct species to an extant one, is presented by that of the hilum to a seed, or of the umbilicus to a mammal. Each of these is a legible and undeniable, record of a being, whose individuality was totally distinct from that of the being by which it is presented, and of which all vestiges have disappeared, save this record. Nor is the parallel founded on obscure or rare examples; both the umbilicus and the hilum are generally conspicuous; and both are extensively found in their respective kingdoms, the former pervading the viviparous Vertebrata, the latter characterising the whole of the cotyledonous types of vegetation.

Once more. An objection may arise to the reception of the prochronic principle, on the ground that the examples I have adduced are not to be compared, in point of grandeur, with the mighty revolutions, which are presumed to have written their records in the crust of the globe; and that hence no analogy can be fairly drawn from one to the other. To the philosopher, however, there is no great or small, as there is none in the works of God. We have every reason to believe that He has wrought by the same laws in all portions of his universe: the principle on which an apple falls from the branch to the ground, is the same as that which keeps the planet Neptune in the solar system. I have shown that the principle of prochronic development obtains wherever we are able to test it; that is, wherever another principle, that of cyclicism, exists; whether the cycle be that of a gnat's metamorphosis, or of a planet's orbit. The distinction of great or small, grand or mean, does not apply to it. If it cannot be proved to be universal, it is only because we are not sufficiently acquainted with some of the economies of nature to be able to pronounce with certainty whether they are cyclical or not. I am not aware of any natural process, in which its existence can be absolutely denied.

And this makes all the difference in the world between my position and that of the old simple-minded observers, with which a superficial reader might think it to possess a good deal in common. A century ago, people used to talk of lusus naturæ; of a certain plastic power in nature; of abortive or initiative attempts at making things which were never perfected; of imitations, in one kingdom, of the proper subjects of another, (as plants were supposed to be imitated by the frost on a window-pane, and by the dendritic forms of metals). Still later, many persons have been inclined to take refuge from the conclusions of geology in the absolute sovereignty of God, asking, – "Could not the Omnipotent Creator make the fossils in the strata, just as they now appear?"

It has always been felt to be a sufficient answer to such a demand, that no reason could be adduced for such an exercise of mere power; and that it would be unworthy of the Allwise God.

But this is a totally different thing from that for which I am contending. I am endeavouring to show that a grand law exists, by which, in two great departments of nature at least, the analogues of the fossil skeletons were formed without pre-existence. An arbitrary acting, and an acting on fixed and general laws, have nothing in common with each other.

Finally, the acceptance of the principles presented in this volume, even in their fullest extent, would not, in the least degree, affect the study of scientific geology. The character and order of the strata; their disruptions and displacements and injections; the successive floras and faunas; and all the other phenomena, would be facts still. They would still be, as now, legitimate subjects of examination and inquiry. I do not know that a single conclusion, now accepted, would need to be given up, except that of actual chronology. And even in respect of this, it would be rather a modification than a relinquishment of what is at present held; we might still speak of the inconceivably long duration of the processes in question, provided we understand ideal instead of actual time; – that the duration was projected in the mind of God, and not really existent.

The zoologist would still use the fossil forms of non-existing animals, to illustrate the mutual analogies of species and groups. His recognition of their prochronism would in nowise interfere with his endeavours to assign to each its position in the scale of organic being. He would still legitimately treat it as an entity; an essential constituent of the great Plan of Nature; because he would recognise the Plan itself as an entity, though only an ideal entity, existing only in the Divine Conception. He would still use the stony skeletons for the inculcation of lessons on the skill and power of God in creation; and would find them a rich mine of instruction, affording some examples of the adaptation of structure to function, which are not yielded by any extant species. Such are the elongation of the little finger in Pterodactylus, for the extension of the alar membrane; and the deflexion of the inferior incisors in Dinotherium, for the purposes of digging or anchorage. And still would he find, in the fossil forms, evidences of that complacency in beauty, which has prompted the Adorable Workmaster to paint the rose in blushing hues, and to weave the fine lace of the dragonfly's wing. The whorls of the Gyroceras, the foliaceous or zigzag sutures of the Ammonites, and the radiating pattern of Smithia, are not less elegant than anything of the kind in existing creation, in which, however, they have no parallels. In short, the readings of the "stone book" will be found not less worthy of God who wrote them, not less worthy of man who deciphers them, if we consider them as prochronically, than if we judge them diachronically, produced.

Here I close my labours. How far I have succeeded in accomplishing the task to which I bent myself, it is not for me to judge. Others will determine that; and I am quite sure it will be determined fairly, on the whole. To prevent misapprehension, however, it may be as well to enunciate what the task was, which I prescribed, especially because other (collateral, hypothetical) points have been mooted in these pages.

All, then, that I consider myself responsible for is summed up in these sentences: —

I. The conclusions hitherto received have been but inferences deduced from certain premises: the witness who reveals the premises does not testify to the inferences.

II. The process of deducing the inferences has been liable to a vast incoming of error, arising from the operation of a Law, proved to exist, but hitherto unrecognised.

III. The amount of the error thus produced we have no means of knowing; much less of eliminating it.

IV. The whole of the facts deposed to by this witness are irrelevant to the question; and the witness is, therefore, out of court.

V. The field is left clear and undisputed for the one Witness on the opposite side, whose testimony is as follows: —

"IN SIX DAYS JEHOVAH MADE HEAVEN AND EARTH, THE SEA, AND ALL THAT IN THEM IS."

1

Dr. Lardner; Museum of Science and Art, vol. i. p. 81.

2

As Cuvier, Buckland, and many others. On the question whether the phenomena of Geology can be comprised within the short period formerly assigned to them, the Rev. Samuel Charles Wilts long ago observed: "Buckland, Sedgwick, Faber, Chalmers, Conybeare, and many other Christian geologists, strove long with themselves to believe that they could: and they did not give up the hope, or seek for a new interpretation of the sacred text, till they considered themselves driven from their position by such facts as we have stated. If, even now, a reasonable, or we might say possible solution were offered, they would, we feel persuaded, gladly revert to their original opinion." —Christian Observer, August, 1834.

3

Reflections on Geology.

4

Geology and Geologists.

5

New System of Geology.

6

Mineral and Mosaic Geologies, p. 430.

7

Geology of Scripture.

8

Scriptural Geology, passim.

9

Letter to Buckland, 15, et seq.

10

Origen, Augustine, &c.

11

Testimony of the Rocks, p. 144

12

Discourse (5th Ed.), 115.

13

Sac. Hist. of World.

14

Rec. of Creation.

15

Nat. Theology.

16

Pre-Adamite Earth.

17

Harmony of Scripture and Geology.

18

Christian Observer, 1834.

19

Religion of Geology, Lect. ii.

20

Scripture and Geology.

21

I am not replying to any of these conflicting opinions; else, with respect to this one, I might consider it sufficient to adduce the ipsissima verba of the inspired text. Not a word is said of Adam's being "nine hundred and thirty years old;" the plain statement is as follows: – "And all the days that Adam lived were nine hundred and thirty years." (Gen. v. 5.)

22

"Protoplast," pp. 58, 59; p. 325; 2d. Ed.

23

Unity of Worlds (1856), pp. 488, 493.

24

"A geological truth must command our assent as powerfully as that of the existence of our own minds, or of the Deity himself; and any revelation which stands opposed to such truths must be false. The geologist has therefore nothing to do with revealed religion in his scientific inquiries." —Edinb. Review, xv. 16.

25

Ansted's Ancient World, 18.

26

Ansted's Ancient World, 30.

27

Scripture and Geology, 371. (Ed. 1855.)

28

"It is by no means unlikely that some beds of coal were derived from the mass of vegetable matter present at one time on the surface, and submerged suddenly. It is only necessary to refer to the accounts of vegetation in some of the extremely moist, warm islands in the southern hemisphere, where the ground is occasionally covered with eight or ten feet of decaying vegetable matter at one time, to be satisfied that this is at least possible."

29

Ansted's Anc. World, 75.

30

M'Culloch's System of Geology, i. 506.

31

Origin of Coal.

32

Testimony of the Rocks, p. 78.

33

Mr. Newman suggests that they were "marsupial bats" (Zoologist, p. 129). I have adopted his attitudes, but have not ventured to give them mammalian ears.

34

In Tennant's "List of Brit. Fossils" (1847), but two species – a Brachiopod and a Gastropod – are mentioned as common to the Chalk and the London Clay. They are Terebratula striatula, and Pyrula Smithii.

35

Ansted's Anc. World, 267.

36

Reliquiæ Diluvianæ.

37

Travels through the Alps, p. 19.

38

Prof. Owen, in his admirable account of the Mylodon, has mentioned a fact which brings us very vividly into contact with its personal history. He shows that the animal got its living by overturning vast trees, doing the work by main strength, and feeding on the leaves. The fall of the tree might occasionally put the animal in peril; and in the specimen examined there is proof of such danger having been incurred. The skull had undergone two fractures during the life of the animal, one of which was entirely healed, and the other partially. The former exhibits the outer tables of bone broken by a fracture four inches long, near the orbit. The other is more extensive, and behind, being five inches long, and three broad, and over the brain. The inner plate had in both these cases defended the brain from any serious injury, and the animal seems to have been recovering from the latter accident at the time of its death.

39

Naturalist's Voyage, passim.

40

The Indians of North America knew that the Mastodon had a trunk; a fact which (though the anatomist infers it from the bones of the skull) it is difficult to imagine them to be acquainted with, except by tradition from those who had seen the living animal.

41

Ansted; Phys. Geography, 82.

42

An interesting fact relating to the Brazilian caves was communicated to Dr. Mantell. "M. Claussen, in the course of his researches, discovered a cavern, the stalagmite floor of which was entire. On penetrating the sparry crust, he found the usual ossiferous bed; but pressing engagements compelled him to leave the deposit unexplored. After an interval of some years, M. Claussen again visited the cavern, and found the excavation he had made completely filled up with stalagmite, the floor being as entire as on his first entrance. On breaking through this newly-formed incrustation, it was found to be distinctly marked with lines of dark-coloured sediment, alternating with the crystalline stalactite. Reasoning on the probable cause of this appearance, M. Claussen sagaciously concluded that it arose from the alternation of the wet and dry seasons. During the drought of summer, the sand and dust of the parched land were wafted into the caves and fissures, and this earthy layer was covered during the rainy season by stalagmite, from the water that percolated through the limestone, and deposited calc-spar on the floor. The number of alternate layers of spar and sediment tallied with the years that had elapsed since his first visit; and on breaking up the ancient bed of stalagmite, he found the same natural register of the annual variations of the seasons; every layer dug through presented a uniform alternation of sediment and spar; and as the botanist ascertains the age of an ancient dicotyledonous tree from the annual circles of growth, in like manner the geologist attempted to calculate the period that had elapsed since the commencement of these ossiferous deposits of the cave; and although the inference, from want of time and means to conduct the inquiry with precision, can only be accepted as a rough calculation, yet it is interesting to learn that the time indicated by this natural chronometer, since the extinct mammalian forms were interred, amounted to many thousand years." – (Petrifactions and their Teachings, p. 481.)

43

Bibliothèque Univers., March, 1852.

44

"It is now admitted by all competent persons, that the formation even of those strata which are nearest the surface, must have occupied vast periods, probably millions of years, in arriving at their present state." – Babbage, Ninth Bridgewater Treatise, p. 67.

45

Geology of Central France.

46

"Though perfect knowledge is not possessed, yet there are reasons for believing that the duration of life to testacean individuals of the present race is several years. But who can state the proportion which the average length of life to the individual mollusc or conchifer, bears to the duration appointed by the Creator to the species? Take any one of the six or seven thousand known recent species; let it be a Buccinum, of which 120 species are ascertained, (one of which is the commonly known whelk;) or a Cypræa, comprising about as many, (a well-known species is on almost every mantel-piece, the tiger-cowry;) or an Ostrea (oyster), of which 130 species are described. We have reason to think that the individuals have a natural life of at least six or seven years; but we have no reason to suppose that any one species has died out, since the Adamic creation. May we then, for the sake of an illustrative argument, take the duration of testacean species, one with another, at one thousand times the life of the individual? May we say six thousand years? We are dealing very liberally with our opponents. Yet in examining the vertical evidences of the cessations of the fossil species, marks are found of an entire change in the forms of animal life; we find such cessations and changes to have occurred many times in the thickness of but a few hundred feet of these late-rocks." – Dr. J. Pye Smith, Scripture and Geology, 5th Ed. p. 376.

47

"One of the laminated formations [in Auvergne] may be said to furnish a chronometer for itself. It consists of sixty feet of siliceous and calcareous deposits, each as thin as pasteboard, and bearing upon their separating surfaces the stems and seed-vessels of small water-plants in infinite numbers; and countless multitudes of minute shells, resembling some species of our common snail-shells. These layers have been formed with evident regularity, and to each of them we may reasonably assign the term of one season, that is a year. Now thirty of such layers frequently do not exceed one inch in thickness. Let us average them at twenty-five. The thickness of the stratum is at least sixty feet; and thus we gain, for the whole of this formation alone, eighteen thousand years." – Dr. J. P. Smith, Scripture and Geology, 5th Edition, p. 137.