полная версия

полная версияThe Winter Solstice Altars at Hano Pueblo

Jesse Walter Fewkes

The Winter Solstice Altars at Hano Pueblo

Introduction

The fetishes displayed in their kivas by different phratries during the Winter Solstice ceremony at the Hopi pueblo of Walpi, in northeastern Arizona, have been described in a previous article,1 in which the altar made in the Moñkiva, or "chief" ceremonial chamber, by the Patki and related people has been given special attention. The author had hoped in 18982 to supplement this description by an exhaustive study of the Winter Solstice ceremonies of all the families of the East Mesa, but was prevented from so doing by the breaking out of an epidemic. This study was begun with fair results, and before withdrawing from the kivas he was able to make a few observations on certain altars at Hano which had escaped him in the preceding year.

Walpi, commonly called by the natives Hopiki, "Hopi pueblo," began its history as a settlement of Snake clans which had united with the Bear phratry. From time to time this settlement grew in size by the addition of the Ala, Pakab, Patki, and other phratries of lesser importance. Among important increments in modern times may be mentioned several clans of Tanoan ancestry, as the Asa, Honani, and the like. These have all been assimilated, having lost their identity as distinct peoples and become an integral part of the population of Walpi, or of its colony, Sitcomovi.3 Among the most recent arrivals in Tusayan was another group of Tanoan clans which will be considered in this article. The last mentioned are now domiciled in a pueblo of their own called Hano; they have not yet, as the others, lost their language nor been merged into the Hopi people, but still preserve intact many of their ancient customs.

The present relations of Hano to Walpi are in some respects not unlike those which have existed in the past between incoming clans and Walpi as each new colony entered the Tusayan territory. Thus, after the Patki people settled at the pueblo called Pakatcomo,4 within sight of Old Walpi, they lived there for some time, observing their own rites and possibly speaking a different language much as the people of Hano do today. In the course of time, however, the population of the Patki pueblo was united with the preëpre Walpi families, Pakatcomo was abandoned, and its speech and ritual merged into those of Walpi. Could we have studied the Patki people when they lived at their former homes, Pakatcomo or Homolobi, we would be able to arrive at more exact ideas of their peculiar rites and altars than is now possible. Hano has never been absorbed by Walpi as the Patki pueblos were, and the altars herein described still preserve their true Tanoan characteristics. These altars are interesting because made in a Tanoan pueblo by Tewa clans which are intrusive in the Hopi country, and are especially instructive because it is held by their priests that like altars are or were made in midwinter rites by their kindred now dwelling along the Rio Grande in New Mexico.

The midwinter rite in which the altars are employed is called Tûñtai by the Tewa, who likewise designate it by the Hopi name Soyaluña. This latter term may be regarded as a general one applied to the assemblages of different families in all the kivas of the East Mesa at that time. The name of the Tewa rite is a special one, and possibly the other families who assemble at this time once had or still retain their own names for their celebrations. The Tûñtai altars were brought by the ancestors of the present people of Hano from their old eastern home, and the rites about them are distinctly Tewan, although celebrated at the same time as the Winter Solstice ceremonies of the Hopi families.

Clan Composition of Hano

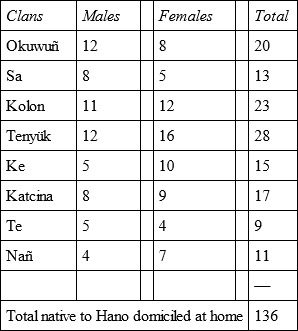

The pueblo called Hano is one of three villages on the East Mesa of Tusayan and contained, according to the writer's census of 1893, a population of 163 persons. It was settled between the years 1700 and 1710 by people from Tcewadi, a pueblo situated near Peña Blanca on the Rio Grande in New Mexico. Although only six persons of pure Tanoan ancestry are now living at Hano, the inhabitants still speak the Tewa dialect and claim as kindred the peoples of San Juan, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Pojoaque, Nambe, and Tesuque.5 The best traditionists declare that their ancestors were invited to leave their old home, Tcewadi, by the Snake chief of Walpi, who was then pueblo chief of that village. They claim that they made their long journey to give aid against the Ute Indians who were raiding the Hopi, and that they responded after four consecutive invitations. The Walpi Snake chief sent them an embassy bearing prayer-sticks as offerings, and although they had refused three invitations they accepted the fourth.

According to traditions the following clans have lived in Hano, but it is not stated that all went to the East Mesa together from Tcewadi: Okuwuñ, Rain-cloud; Sa, Tobacco; Kolon, Corn; Tenyük, Pine; Katcina, Katcina; Nañ, Sand; Kopeeli, Pink Shell; Koyanwi, Turquoise; Kapolo, Crane; Tuñ, Sun; Ke, Bear; Te, Cottonwood; Tayek (?); Pe, Firewood; and Tceta, Bivalve shell.

The early chiefs whose names have been obtained are Mapibi of the Nañ-towa, Potañ of the Ke-towa, and Talekweñ and Kepo of the Kolon-towa. The present village chief is Anote of the Sa-towa or Tobacco clan.6

Of the original clans which at some time have been with the Hano people, the following have now become extinct: Kopeeli, Koyanwi, Kapolo, Tuñ, Tayek, Pe,7 and Tceta. The last member of the Tuñ or Sun people was old chief Kalacai who died about four years ago. It is quite probable that several of these extinct clans did not start from Tcewadi with the others. There were several waves of Tanoan emigrants from the Rio Grande region which went to Tusayan about the same time, among which may be mentioned the Asa, which took a more southerly route, via Zuñi. The route of the Asa people will be considered in another article, and the evidences that some of the Asa clans joined their kindred on their advent into Tusayan will be developed later. Probably certain members of the Katcina clan accompanied the Asa people as far as the Awatobi mesa and then affiliated with the early Hano clans.8

The census of Hano in December, 1898, was as follows:

The above enumeration of Hano population does not include Walpi and Sitcomovi men married to Hano women (23), nor Tewa men living in the neighboring pueblos (15).9 Adding these, the population is increased to 174, which may be called the actual enumeration at the close of 1898. Subsequent mortality due to smallpox and whooping-cough will reduce the number below 160.

In the following lists there are arranged, under their respective clans, the names of all the known inhabitants of Hano. There have been several deaths since the lists were made (December 1, 1898), and several births which also are not included. It will be noted that the majority have Tanoan names, but there are several with names of Hopi origin, for in these latter instances I was unable to obtain any other.10

Census of Hano by ClansOkuwuñ-towa, or Rain-cloud clan. – Men and boys: Kalakwai, Kala, Tcüa, Wiwela, Kahe, Yane, Solo, Yunci, Pade, Klee, Kochayna, Këe (12). Women and girls: Sikyumka, Kwentce, Talitsche, Yoyowaiolo, Pobitcanwû, Yoanuche, Asou, Tawamana (8). Total, 20.

Sa-towa, or Tobacco clan. – Men and boys: Anote, Asena, Tem[)e], Ipwantiwa, Howila, Nuci, Yauma, Satee (8). Women and girls: Okañ, Heli, Kotu, Kwañ, Mota (5). Total, 13.

Kolon-towa, or Corn clan. – Men and boys: Polakka, Patuñtupi, Akoñtcowu, Komaletiwa, Agaiyo, Tcid[)e], Oba, Toto, Peke, Kelo, Tasce (11). Women and girls: Kotcaka, Talikwia, Nampio, Kweñtcowû, Heele, Pelé, Kontce, Koompipi, Chaiwû, Kweckatcañwû, Awatcomwû, Antce (12). Total, 23.

Tenyük-towa, or Pine clan. – Men and boys: Tawa, Nato, Wako, Paoba, Topi, Yota, Pobinelli, Yeva, Tañe, Lelo, Sennele, Poctce (12). Women and girls: Toñlo, Hokona, Kode(?), Sakpede, Nebenne, Tabowüqti, Poh[ve], Saliko, Eye, Porkuñ, Pehta, Hekpobi, Setale, Naici, Katcine, Tcenlapobi (16). Total, 28.

Ke-towa, or Bear clan. – Men and boys: Mepi, Tae, Tcakwaina, Poliella, Tegi (5). Women and girls: Kauñ, Kalaie, Pene, Tcetcuñ, Kala, Katcinmana, Selapi, Tolo, Pokona, Kode (10). Total 15. Tcaper ("Tom Sawyer") may be enrolled in this or the preceding family. He is a Paiute, without kin in Hano, and was sold when a boy as a slave by his father. His sisters were sold to the Navaho at the same time. Tcaper became the property of an Oraibi, later of a Tewa man, now dead, and so far as can be learned is the only Paiute now living at Hano.

Katcina-towa.– Men and boys: Kwevehoya, Taci, Avaiyo, Poya, Oyi, Wehe, Sibentima, Tawahonima (8). Women and girls: Okotce, Kwenka, Awe, Peñaiyo, Peñ, Poñ, Tcao, Poschauwû, Sawiyû (9). Total, 17.

Te-towa, or Cottonwood clan. Men and boys: Sania, Kuyapi, Okuapin, Ponyin, Pebihoya (5). Women and girls: Yunne, Pobitche, Poitzuñ, Kalazañ (4). Total, 9.

Nañ-towa, or Sand clan. – Men and boys: Puñsauwi, Pocine, Talumtiwa, Cia (4). Women and girls: Pocilipobi, Talabensi, Humhebuima, Kae, Avatca, "Nancy," Simana (7). Total, 11.

The present families in Hano are so distributed that the oldest part of the pueblo is situated at the head of the trail east of the Moñkiva. This is still owned and inhabited by the Sa, Kolon, and Ke clans, all of which probably came from Tcewadi. The Katcina and related Tenyük, as well as the Okuwuñ and related Nañ clans, are said, by some traditions, to have joined the Tewa colonists after they reached the Hopi mesas, and the position of their houses in respect to the main house-cluster favors that theory. Other traditions say that the first pueblo chief of the Tewa was chief of the Nañ-towa. Too much faith should not be put in this statement, notwithstanding the chief of the Tewakiva belongs to the Nañ-towa. It seems more probable that the Ke or Bear clan was the leading one in early times, and that its chief was also kimoñwi or governor of the first settlement at the foot of the mesa.

Tewa Legends

According to one authority (Kalakwai) the route of migration of the Hano clans from their ancient home, Tcewadi, led them first to Jemesi (Jemez), where they rested a year. From Jemesi they went to Orpinpo or Pawikpa ("Duck water"). Thence they proceeded to Kepo, or Bear spring, the present Fort Wingate, and from this place they continued to the site of Fort Defiance, thence to Wukopakabi or Pueblo Ganado. Continuing their migration they entered Puñci, or Keam's canyon, and traversing its entire length, arrived at Isba, or Coyote spring, near the present trail of the East Mesa, where they built their pueblo. This settlement (Kohti) was along the foot-hills to the left of the spring, near a large yellow rock or cliff called Sikyaowatcomo ("Yellow-rock mound"). There they lived for some time, as the debris and ground-plan of their building attest. Their pueblo was a large one, and it was conveniently near a spring called Uñba, now filled up, and Isba, still used by the Hano people.

Shortly after their arrival Ute warriors made a new foray on the Hopi pueblos, and swarmed into the valley north of Wala,11 capturing many sheep which they drove to the hills north of the mesa.12 The Tewa attacked them at that place, and the Ute warriors killed all the sheep which they had captured, making a protecting rampart of their carcasses. On this account the place is now called Sikwitukwi ("Meat pinnacle"). The Tewa killed all but two of their opponents who were taken captives and sent home with the message that the Bears had come, and if any of their tribe ever returned as hostiles they would all be killed. From that time Ute invasions ceased.

According to another good authority in Tewa lore, the Asa people left "Kaëkibi," near Abiquiu, in northern New Mexico, about the time the other Tewa left Tcewadi They traveled together rapidly for some time, but separated at Laguna, the Asa taking the southern route, via Zuñi. The Tewa clans arrived first (?) at Tusayan and waited for the Asa in the sand-hills near Isba. Both groups, according to this authority, took part in the Ute fight at Sikwitukwi, and when they returned the village chief of Walpi gave the Asa people for their habitation that portion of the mesa top northeast of the Tewakiva, while the present site of Hano was assigned to the Tewa clans. During a famine the Asa moved to Tübka (Canyon Tsegi, or "Chelly"), where they planted the peach trees that are still to be seen. The ruined walls east of Hano are a remnant of the pueblo abandoned by them. The Asa intermarried with the Navaho and lost their language. When they returned to the East Mesa the Hopi assigned to them for their houses that part of Walpi at the head of the stairway trail on condition that they would defend it.13

In view of the tenacity with which the women of Hano have clung to their language, even when married to Hopi men, it seems strange that the Asa lost their native dialect during the short time they lived in Tsegi canyon; but the Asa men may have married Navaho women, and the Tanoan tongues become lost in that way, the Asa women being in the minority. There is such uniformity in all the legends that the Asa were Tanoan people, that we can hardly doubt their truth, whatever explanation may be given of how the Asa lost their former idiom.

In 1782 Morfi described Hano,14 under the name "Tanos," as a pueblo of one hundred and ten families, with a central plaza and streets. He noted the difference of idiom between it and Walpi. If Morfi's census be correct, the pueblo has diminished in population since his time. Since 1782 Hano has probably never been deserted, although its population has several times been considerably reduced by epidemics.

In return for their aid in driving the Ute warriors from the country, the Hopi chief gave the Tewa all the land in the two valleys on each side of the mesa, north and east of a line drawn at right angles to Wala, the Gap. This line of demarcation is recognized by the Tewa, although some of them claim that the Hopi have land-holdings in their territory. The line of division is carefully observed in the building of new houses in the foot-hills, for the Hopi families build west of the line, the Tewa people east of it.

Differences in Social Customs

A casual visitor to the East Mesa would not notice any difference between the people of Hano and those of Walpi, and in fact many Walpi men have married Tanoan women and live in their village. The difference of idiom, however, is immediately noticeable, and seems destined to persist. Almost every inhabitant of Hano speaks Hopi, but no Hopi speaks or understands Tewa. While there are Tewa men from Hano in several of the Hopi villages, where they have families, no Tewa woman lives in Walpi. This is of course due to the fact that the matriarchal system exists, and that a girl on marrying lives with her mother or with her clan, while a newly married man goes to the home of his wife's clan to live.

There are differences in marriage and mortuary customs, in the way the women wear their hair,15 and in other minor matters, but at present the great difference between the Hopi and the Tewa is in their religious ceremonials, which, next to language, are the most persistent features of their tribal life. Hano has a very limited ritual; it celebrates in August a peculiar rite known as Sumykoli, or the sun prayer-stick making, as well as the Tûñtai midwinter ceremony, the altars of which are described herein. There are also many Katcina dances which are not different from those performed at Walpi. One group of clown priests, called Paiakyamû, is characteristic of Hano. Compared with the elaborate ritual of the Hopi pueblo, that of Hano is poor; but Tewa men are members of most of the religious societies of Walpi, and some of the women take part in the basket dance (Lalakoñti) and Mamzrauti, in that village.

The following Tewa names for months are current at Hano:

January, Elo-p'o, "Wooden-cup moon"; refers to the cups, made of wood, used by the Tcukuwympkiyas in a ceremonial game.

February, Káuton-p'o, "Singing moon."

March, Yopobi-p'o, "Cactus-flower moon." The element pobi16 which is so often used in proper names among the Tewa, means flower.

April, Púñka-p'o, "Windbreak moon."

May, Señko-p'o, "To-plant-secretly moon." This refers to the planting of sweet corn in nooks and crevices, where children may not see it, for the Nimán-katcina.

June-October, nameless moons, or the same names as the five winter moons.

November, Céñi-p'o,17 "Horn moon," possibly referring to the Aaltû of the New-Fire ceremony.

December, Tûñtai-p'o, "Winter-solstice moon."

Contemporary Ceremonies

The Winter Solstice ceremony is celebrated in Walpi, Sitcomovi, and Hano, by clans, all the men gathering in the kivas of their respective pueblos. The Soyaluña is thus a synchronous gathering of all the families who bring their fetishes to the places where they assemble. The kivas or rooms in which they meet, and the clans which assemble therein, are as follows:

WalpiMoñkiva: Patki, Water-house; Tabo, rabbit; Kükütce, Lizard; Tuwa, Sand; Lenya, Flute; Piba, Tobacco; and Katcina.

Wikwaliobikiva: Asa.

Nacabkiva: Kokop, Firewood; Tcüa, Snake.

Alkiva: Ala, Horn.

Tcivatokiva: Pakab, Reed; Honau, Bear.

SitcomoviFirst Kiva: Patki, Water-house; Honani, Badger.

Second Kiva: Asa.

HanoMoñkiva: Sa, Tobacco; Ke, Bear; Kolon, Corn, etc.

Tewakiva: Nañ, Sand; Okuwuñ, Rain-cloud, etc.

The altars or fetishes in the five Walpi kivas are as follows:

The altar described in a former publication18 is the most elaborate of all the Winter Solstice fetishes at Walpi, and belongs to the Patki and related clans.

The Asa family in the Wikwaliobikiva had no altar, but the following fetishes: (1) An ancient mask resembling that of Natacka and called tcakwaina,19 attached to which is a wooden crook and a rattle; (2) an ancient bandoleer (tozriki); and (3) several stone images of animals. The shield which the Asa carried before the Moñkiva altar had a star painted upon it.

The Kokop and Tcüa families, in the Nacabkiva, had no altar, but on the floor of the kiva there was a stone image which was said to have come from the ancient pueblo of Sikyatki, a former village of the Kokop people.

There was no altar in the Alkiva, but the Ala (Horn) clan which met there had a stone image of Püükoñhoya, and on the shield which they used in the Moñkiva there was a picture of Alosaka.

The Pakab20 (Reed or Arrow) people had an altar in the Tcivatokiva where Pautiwa presided with the típoni or palladium of that family.

The writer was unable to examine the fetishes of the Honani and Asa clans, who met in the two Sitcomovi kivas. It was reported that they have no altars in the Soyaluña, but a study of their fetishes will shed important light on the nature of the rites introduced into Tusayan by these clans. Tcoshoniwa is chief in one of these kivas.21

Pocine, chief of the Tewakiva, belongs to the Nañ-towa, or Sand clan, and is the elder son of Pocilipobi. Puñsauwi, his uncle, is Pocilipobi's brother. As the kimoñwi or village chief of the Tewa colonists, when they came into Tusayan, belonged to the Sand clan, we may suppose this altar to be hereditary in this family.

Anote, the chief of the Moñkiva of Hano, is the oldest man of the Sa-towa or Tobacco clan. Satele, who assisted him in making the altar, is a member of the Ke or Bear clan. Patuñtupi, who was present when the altar was made at Hano, belongs to the Kolon or Corn clan.

The Winter Solstice Ceremony

The Tûñtai or Soyaluña ceremony of the East Mesa in 1898 extended from December 9th to the 19th inclusive, and the days were designated as follows:

9th, Tcotcoñyuñya (Tcotcoñya), Smoke assembly.

10th, Tceele tcalauûh, Announcement.

11th, Cüs-tala, First day.

12th, Lüc-tala, Second day.

13th, Paic-tala, Third day.

14th, Yuñya, Assemblage.

15th, Sockahimû.

16th, Komoktotokya.

17th, Totokya, Totokpee.

18th, Pegumnove.

19th, Navotcine.

The active secret ceremonies began on the 14th and extended to the 19th. Yuñya was the day on which the Walpi chiefs entered their kivas, and Totokya that on which the most important secret rites were performed.

Tcotcoñyuñya, Smoke assembly. The time of the Soyaluña is fixed by Kwatcakwa, Sun-priest of the Patki clan, who determines the winter solstice by means of observations of sunset on the horizon, as elsewhere described. The Smoke assemblage at Walpi occurred after sunset on December 9th, in the house of Anwuci's wife, adjoining the Moñkiva, and was attended by Supela, Kwatcakwa, Sakwistiwa, Kwaa, and Anawita, all chiefs belonging to the Patki clan. The Smoke assemblage at Hano, preliminary to the Tûñtai, was also held after sunset on December 9th, and was attended by the following chiefs: Anote (Tem[)e]), Sa-towa; Satele, Ke-towa; Pocine (Koye), Nañ-towa; Patuñtupi, Kolon-towa.

There was no formal notification of Tûñtai from the housetops of Hano on the following morning, the Soyaluña announcement from Walpi serving all three pueblos on the East Mesa.

The formal announcement was made by Kopeli at daybreak of December 10th. Hoñyi, the regular tcakmoñwi, or town-crier, was snowbound at Keam's Canyon, and consequently was unable to perform this function.

The Smoke assemblage and its formal announcement at daybreak on the following morning have been observed in the Snake dance, and in the Flute, New-fire, and Soyaluña ceremonies; it probably occurs also in the Lalakoñti and Mamzrauti. It takes place several days before the Assembly day, when the chief enters the kiva and sets his natci or standard on the kiva hatch to announce that he has begun the ceremonies.

Kivas at Hano

There are two kivas in Hano, one of which, called Tewakiva, is situated at the head of the trail to the pueblo. The other, called the Moñkiva, is built in the eastern part of the plaza, and, as its name implies, is the "chief" Hano kiva. Both these semi-subterranean rooms are rectangular22 in shape, and in structural details resemble the kivas of Walpi. Each has a hatchway entrance in the middle of the roof, and is entered by means of a ladder which rests on the floor near a central fireplace. Neither of the Hano kivas has a window, but each has a raised platform for spectators east of the fireplace.23

Altar in the Moñkiva at Hano

Anote,24 the chief of the Moñkiva, constructed his altar (plate XVIII) on the day above mentioned as Paic-tala. He anticipated the others in making it, and began operations, about 10 A.M., by carefully sweeping the floor. His fetishes and other altar paraphernalia were in a bag on the floor at the western end of his kiva, but there was no típoni, or chieftain's badge, even on the completed altar.