полная версия

полная версияDecadence and Other Essays on the Culture of Ideas

In the second case, the external ideas that have entered the brain are disintegrated there and unite their atoms with the other atomic knowledge already within us. An idea is digested, assimilated. Assimilated, it then becomes very different from what it was when it entered the intelligence. Like intestinal absorption, mental absorption is, therefore, an excellent though indirect way of acquiring knowledge. In both cases, the ideas, like the aliments, will be known, not immediately, but by their effects. Thus men know hereditarily that certain ideas are individual or social poisons, and that others are equally favourable to the welfare of the individual or to the development of a people. But, in this order, notions of utility and of harmfulness are much less precise. We have seen a certain idea, reputed to be very dangerous, contributing to the health of a man, of a family, of a society, of civilization itself. Ideas are extremely workable, plastic. They take the shape of the brain. There are perhaps no ideas that are bad for a healthy brain whose form is normal. There are perhaps no good ones for a brain that is sick and warped.

III

But let us come back to our tree or our ox. This ox can enter us in one of two ways. First, partly, but really, in the form of food. What we absorb of it in that way cannot, evidently, be known as ox. It reaches our knowledge only through its effects – strength, health, gaiety, activity, depression. Even were this absorption total in the case of a small animal, digestible in all its parts, the result, from the point of view of immediate knowledge, would be the same, since the object becomes resolved into elements which render its form unknowable.

The other manner – that which brings into play the external senses – will make us know the ox, in appearance as such, in reality as image of an ox. What is the true value of this knowledge? We must here return to this question, in order to enter more easily upon the second part of this essay.

Truth has been very seriously defined as conformity of the representation of an object with this object itself. But that solves nothing. What is the object itself, since we can know it only as representation? It is useless to carry the discussion further. We shall turn indefinitely around the fortress of idealism, without ever finding an opening, or any weak point. We shall enter it never, no argument serving as a bomb against its solid walls.

However, we must consider carefully. Having thoroughly reflected, we shall ask if this fortress be real, or if, on the contrary, it be not, perhaps, a representation without object, a pure phantom, like those sunken cities whose bells still ring for great festivals, but are heard only by those who believe in their mysterious life. This doubt will lead us to re-examine the reasoning of Berkeley and of Kant, and see if it be well constructed. Does it start from the senses to reach the mind? Or may it not, perchance, be one of those mental conceptions which fall back upon the senses like an avalanche, freezing and smothering them?

How have the senses been formed? Such is the question. Has there always been an opposition between the ego and the non-ego? There is nothing in the intelligence that has not first been in the senses. By intelligence, we must in this philosophic dictum, due to Locke, understand the psychologic consciousness. Let us leave aside the consciousness, which can only serve to complicate the problem. Consciousness is a phenomenon of secondary order and of an entirely sentimental utility, if it be restricted to man; commonplace and of pure reflex, if extended to all sensible matter. Let us consider this matter in perhaps its humblest manifestations, taking account only of the actions and reactions, exactly as we might observe the influence of heat, of light, or of cold on milk, wine or water. In living matter there will, however, be something more – the decomposition will be compensated by assimilation, and if the assimilation be abundant, there will be generation. Other forms, resembling the first, will detach themselves from the matrix form. This represents life essentially, a living being, a being limited in duration by the very fact of its growth, which constitutes an effort and a loss. Let us consider a being whose senses are not differentiated, and let us see how it gets on with the rest of the world, how it knows it.

The amoeba has no exterior senses. It is an almost homogeneous mass, and yet it is sensible to almost the same sensorial impressions as the highest mammal. It feeds (smell and taste); it moves (sense of space, touch); it is sensible to light, at least to certain rays (sight); its environment being in perpetual movement, ceaselessly traversed by sonorous waves, it doubtless reacts to these vibrations (hearing). Perhaps, even, it possesses, without special organs, senses which we lack, and which we recover only by study and analysis, such as the chemical sense, which judges the composition of a body, declares it assimilable or counsels its rejection. The exercise of all these senses denotes, first of all, a very long heredity. They have, doubtless, been acquired successively only, unless, the absence of one of them being capable of causing death, their presence is the strict consequence of the life of this humble beast. But it is useless to construct any hypotheses on the subject. It is enough to keep to the fact, and this fact is the existence of a being without differentiated organs, that is to say, a being all of whose parts are equally adapted to react against every external excitation.

Why these reactions? They are one of the conditions of life. But could not life be conceived without them? It is possible. It is a question of environment. If the amoeba's environment were homogeneous and calm, if it were of a constant temperature and luminosity, if it furnished an abundance of proper nourishment, if, in a word, the animal dwelt in an alimentary bath, no reactions would be necessary, and its only movement would be to open its pores for food, to reject the excess of this food, to divide itself, when swollen, into two amoebas. Why, then, does it possess all these senses which, though unorganized, are perfectly real? Because the environment obliges it to have them, because of its instability. The senses, whether differentiated, or spread over the entire surface of a living form, are the creation of the environment which – light, sound, material exteriority, odours, etc. – acts in accordance with different discontinuous manifestations. Constant or continuous, they would be without effect. Discontinuous, they make themselves felt. Discontinuous light has created the eye, just as the drop of water creates a hole in granite.

A being, whatever it may be, whether vague and almost amorphous or clearly defined, is not isolated in the universal vital environment. It is the molecule of a diapason. It vibrates, not of its own accord, but in obedience to a general movement. The living cell, itself in internal movement and subjected to all the reactions of external movement, perceives this movement doubtless as an unique impression only. But when several cells come together and live in permanent contact, the impressions of external movement begin to be perceived as differentiated. Is this then necessary? Do there then already exist luminous vibrations, different from sonorous vibrations? Assuredly, since otherwise the sensorial differentiation would be inexplicable, being useless. The union of several cells permits the animal to divide its work of perception, and to present to each perceptible manifestation an organ or, at least, the sketch of an organ, appropriate to receive it.

It would be possible, it is true, from the idealistic point of view, to suppose that the senses are a creation of the individual, an enhancement of his own life, and that he differentiates, on his own initiative, his cinematic impression. This would be a phenomenon of spontaneous analytic creation, the analyzing instrument existing prior to the matter analyzed, or even, for exasperated idealists, creating this matter according to determinate needs, once and for all, by its own physiology. It would then be a property of organized living matter to fabricate senses for itself, and to diversify, by this means, its own life. This point of view is not easy to admit for several reasons, purely physical.

First, if this sensorial differentiation were a faculty of living matter, it would not be observed to be limited in its powers, as it is. Even admitting certain senses unknown to man, such as the chemical sense, the electric sense, the sense of orientation (extremely doubtful), it is still seen that the number of senses is very limited. But, far more important, the fundamental senses are found to be identical among the majority of the higher species, vertebrates and insects, with very few exceptions. The moment the animal arrives at sensorial differentiation, this differentiation occurs in response to the manifestations of matter.

The senses should, then, correspond to external realities. They have been created, not by the perceiving being, but by the perceptible environment. It is the light that has created the eye, just as, in our houses, it has created the windows. Where there is no light, fish become blind. This is perhaps the direct proof, for if light is the creation of the eye, this creation can occur at the bottom of the sea quite as well as on the surface of the earth. Another proof: these same fish, having become blind, but still requiring a luminous habitat, create for themselves in the night of the abysses, not eyes, but apparatus directly productive of light; and this artificial light creates anew the atrophied eye. The senses are then clearly the product of the environment. That is all they can do, moreover, their utility being nil, if the environment is not perceptible. It might still be objected that it is the nervous system which, having intuition of an environment to be perceived, creates for itself organs adapted to this perception. But this is merely begging the question; for, either the nervous system has knowledge of the external environment, which means that it already has senses, or else it has no senses, and thus can have no knowledge. A more serious objection would be that, sensorial aptitude being a property of the nervous system, it would afterwards create for itself organs in order to perceive more distinctly, and clearly differentiated, the various natural phenomena. This view would explain up to a certain point the creation of sensorial organs, but not the existence of the senses themselves as sensitive power. It is, moreover, certain that the nervous system acts rather by tyrannizing the organs at its disposal, than by seeking to modify these organs or to create new ones. It is a power which evidently exceeds the limits of its capacity. It has, on the contrary, devolved upon the external phenomena which, in acting mechanically on the living matter, produce in it local modifications. The organs of the senses seem to be nothing other than surfaces sensitized by the very agents which, once their work is done, will reflect in them their particular physiognomy. The eye – let us take once more this example, and repeat it – is a creation of light.

Since they are themselves the work of the principal general phenomena, the senses ought then to agree exactly – allowing for approximation – with the very nature which has created them. The luminous environment is not, in this case, a dream, but a reality, and a reality existing prior to the eye which perceives it; and, since the eye is the very product of light, objects situated in this luminous environment should be perceived by it as an exact image, just as the drill which creates a hole, creates it strictly to its size, its form, its image. Bacon said that the senses are holes. Here this is only a metaphor.

IV

There remains the question of the co-ordination of the impressions received materially by the senses. This co-ordination, for elementary sensations, is evidently identical for all beings. The snail, his horn being threatened, and man, his eye, make the same shrinking movement. Identical acts can have as cause only identical realities, or ones perceived as such. With judgment, we enter upon the mystery. If light is constant, the judgment which admits its existence is variable according to the species, and, in the higher species, according to the individual. It is clear that all eyes are affected by light, but we do not know to what degree, or according to what mode of spectral decomposition. It is the same for all other senses. Even if the reality of the sensible world be admitted, we are obliged to pronounce cautiously upon the quality of this reality, as reality perceived and judged. We then return to idealism, though having had a quite different end in view. We must retrace our steps, contemplate anew the ironic portress, and resign ourselves never to know anything save appearance.

Another fact, however, remains – another fortress, perhaps, reared facing the other. This is, that matter existed before life. The gain seems slight, but it is equivalent to saying that the phenomena perceived by the senses are exterior to the senses which now perceive them; and this perhaps means that, if life becomes extinct, matter will survive life. The proposition of the idealists that the world would come to an end if there were no longer any sensibilities capable of feeling it, any intelligences capable of perceiving it, seems, therefore, untenable. And yet what would a world be, that was neither thought nor felt? We must recognize this, that when we think of a world void of thought, it still contains our thought, or it is our thought which contains it and animates it. Another phenomenon analogous to this has, perhaps, contributed much to belief in the immortality of the soul, namely, that we cannot conceive of ourselves as dead save by thinking of this death, by feeling and seeing it. The idea of our non-existence supposes, moreover, the life of our thought. That there is here an illusion due to the very functioning of the mechanism of thought is probable enough; but it is difficult not to take it into account. It would seem somewhat high-handed to make abstraction of it.

We can attempt it, however, and try a new road leading "beyond thought." The way would be to consider the general movement of the things in which our thought itself is closely implicated, and by which it is rigorously conditioned. Far, perhaps, from thought thinking life, it is life that animates thought. What is anterior is a vast rhythmic undulation, of which thought is but one of the moments, one of the bounds.

The position taken by man outside the world to judge the world, is a factitious attitude. It is, perhaps, only a game, and one that is too easy. The division of man into two parts, thought, physical being, one considering the other and pretending to contain it, is only a philosophic amusement which becomes impossible the moment we stop to consider. There is, in fact, a physic of thought. We know that it is a product, measurable, ponderable. Unformulated externally, it nevertheless manifests its physical existence by the weight which it imposes upon the nervous system. It needs speech, writing, or some sort of sign, in order to manifest itself externally. Telepathy, thought, penetration, presentiment – if there be any facts in this category which have really been verified – would in such a case be so many proofs of the materiality of thought. But it is useless to multiply arguments in favour of a fact which is no longer contested save by theology.

This fact of materiality gives thought a secondary place. It is produced. It might not be. It is not primordial. It is a result, a consequence – doubtless a property of the nervous system, or even of living matter. It is then through a singular abuse, that we have become accustomed to consider it isolated from the ensemble of its producing causes.

But, if thought be a product, it is, none the less, productive in its turn. It does not create the world, it judges it. It does not destroy it, it modifies and reduces it to its measure. To know is to frame a judgment; but every judgment is arbitrary, since it is an accommodation, an average, and since two different physiologies give different averages, just as they give different extremes. The path, once again, after many windings, brings us back to idealism.

Idealism is definitely founded on the very materiality of thought, considered as a physiological product. The conception of an external world exactly knowable is compatible only with belief in the reason, that is to say, in the soul, that is to say, furthermore, in the existence of an unchangeable, incorruptible, immortal principle, whose judgments are infallible. If, on the contrary, knowledge of the world be the work of a humble physiological product, thought – a product differing in quality, in modality, from man to man, species to species – the world may perhaps be considered as unknowable, since each brain or each nervous system derived from its vision and from its contact a different image, or one which, if it was at first the same for all, is profoundly modified in its final representation by the intervention of the individual judgment.

If the same object produces the same image on the retina of an ox or the retina of a man, it will not, doubtless, be concluded, therefore, that this image is known and judged identically by the ox and the man.

There are no two leaves, there are no two beings, alike in nature. Such is the basis of idealism and the cause of incompatibility with the agreeable doctrines with which men continue to be entertained.

The reasons of idealism plunge deep down into matter. Idealism means materialism, and conversely, materialism means idealism.

1904.

1

Les Travailleurs de la Mer, 2nd part, 1st Book, VII.

2

Technical term.

3

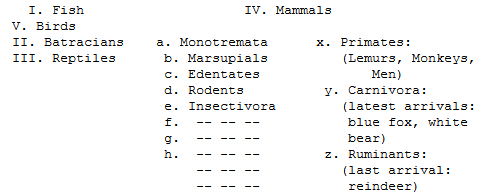

Communication à l'Académie des Sciences (13 Avril 1896), certified and rendered more precise by later investigations which M. Quinton has explained to me. Here, without scientific apparatus, is what, as a result of precious conservations, would appear to be the general order in which the animals appeared, beginning with the fishes, and taking account only of those which have yet been covered:

The bearing of this list upon any question whatsoever of general philosophy is evident for all who know how to disassociate ideas. It would have thrilled Voltaire. For the rest, I claim the honour of having been the first to announce to the larger public these new scientific views, which will, logically, have a magnificent wealth of consequences. I have already made a less precise allusion to them, notably in the Wiener Rundschau, May 1899.

4

Intelligence can thus be conceived as an initial form of instinct, in which case the human intelligence would be destined to crystallize into instinct, as has occurred in the case of other animal species. Consciousness would disappear, leaving complete liberty to the unconscious act, necessarily perfect in the limits of its intention. The conscious man is a scholar who will reveal himself a master the moment he has become a delicate but unerring machine, like bee and beaver.

5

La Survivance de l'Ame et l'idée de justice chez les peuples non civilisés, Paris, Leroux, 1894.

6

Des Réputations littéraires: Essai de morale et d'histoire. Première série. Paris, Hachette, 1893.

7

Livres perdus: Essai bibliographique sur les livres devenus introuvables, by Philoumeste Junior, Brussels, 1882.

8

These privately printed editions of three hundred copies or less have necessarily been worn out in proportion to their success.

9

Opera et Fragmenta veterorum poetarum latinorum. London, 1713

10

Opus cit., p. 103.

11

This was written on the appearance of M. Louis Proal's work, Le Crime et le Suicide Passionnels (F. Alcan, 1910), in which, referring to sex dramas in the criminal courts, Racine is quoted, every ten pages, for reference and comparison. Everyone hesitates to say just what an age of passion and of carnal madness the Grand Siècle really was.

12

L'Étang. This poem forms part of the set of five odes in which Racine celebrated Port-Royal des Champs: L'Étang, Les Prairies, Les Bois, Les Troupeaux, Les Jardins.

13

Le Promenoir des Deux Amans.

14

Vapereau, Dictionnaire des Littératures.

15

An excellent doctor's thesis on Tristan l'Hermite, by M. V. M. Demadin, bears precisely this title: Un précurseur de Racine.

16

The first volume, and that alone, of Restif de la Bretonne's Monsieur Nicholas should be excepted.

17

Recueil de quelques pièces nouvelles et galantes, tant en prose qu'en vers. Cologne, 1667.

18

Paris, published by Jacques Dugast, aux Gants Couronnez, 1632.

19

At the Hôtel de Bourgogne, while at Giénégaud his rival Pradon's play was received with great applause.

20

Bayle. And Racine, recognizing his adversary's craft, said: "The whole difference between me and Pradon is that I know how to write."

21

In another essay, Women and Language, I have considered the lie as the mark of man as opposed to the animal. The superiority of a race, of a group of living beings, is in direct ratio to its power of falsehood – that is to say, reaction against reality. The lie is only the psychological form of the Vertebrate's reaction against its environment. Nietzsche, anticipating science, says: "The lie is a condition of life."

22

There is a presentiment of this in Montesquieu's remark, recently published; it is conformity that constitutes beauty Æsthetics. Father Buffier has defined beauty as the assembling of the commonest elements. When his definition is explained, it is excellent. Father Buffier says that beautiful eyes are those resembling the greatest number of other eyes; the same with the mouth, the nose, etc. It is not that there are not a great many more ugly noses than beautiful ones, but that the former are of many different sorts, and that each sort of ugly noses is much smaller in number than the beautiful sort. It is as if, in a crowd of a hundred men, there were ten dressed each in a different colour; it is the green that would predominate.

23

"A work," continues the translator, "which can profit the reader, and which brings marvellous contentment to those who frequent the courts of the grands seigneurs, and who wish to learn how to talk of an infinite number of things opposed to the common opinion." S. 1. 1603.

24

L'Appel au soldat.

25

Someone remarked in the course of a conversation: "The peasant is a real person; he is a scientist, a physicist." All modern political effort tends to turn the physicist into a metaphysician. This effort is well under way for the working-man, who begins to despise toil and value phrases. His surprise is great when he finds that the word has no effect upon reality.

26

De Kant à Nietzsche.

27

The idea of thus introducing attention into the world through woman is M. Ribot's, in his Psychologie de l'attention.

28

Copulation would have sufficed for that. Life in common, after fertilization, is extremely rare, except among primates and birds. Among carnivorous insects, the union is often mortal for the male whom the stronger female devours.