полная версия

полная версияSocial Work; Essays on the Meeting Ground of Doctor and Social Worker

Make a person face "the worst" and you disarm its terrors.

"But suppose I get faint on the street?"

"Well, you probably will just sit down on the curbstone until you come to."

That remark does not sound as if it would reassure a person even if made with a laugh. But it does, because he is thereby freed of a fear of something much worse, a fear that lurks in the background of his mind.

There is one other thing to be said about the treatment of fears. If a person fears to do any particular act, such as going to church or into the subway, if he fears to be alone in crossing a big square, if he fears to get into a crowd (all these are common fears), the most important thing is to force him to do what he most fears.

"Do the thing you are afraid of, or soon you will be afraid of something else as well. And the more you do what you fear to do, the less you will be afraid of it, because your act will bring you evidence of the truth. Your act will prove to you that you can do the thing that you fear you cannot. That fact will convince you a great deal more than all the talking that your doctor or anybody else can do. You will get conviction by reality, the best of all witnesses."

Among the poor, with whom we deal part of the time in social work – though I insist that social work is concerned with the rich as well – we have to face economic fears. In America and England economic fears are a very real evil – fears of the work-house, fears of coming to be dependent, of having no place of their own, are what poor people often dread. Again, the clue for our usefulness is to find out what people do not tell us of these economic fears, and then to see if we can make them groundless.

In a certain number of people (I do not feel competent to say how large a portion), life is rendered miserable by the fear of being found out. I happened, as I have already said, to get driven some years ago into a position where I thought it best to swear off medical lying. One of the surprising parts of this experience was the sense of relief which I felt when I knew that there was no longer anything in my medical work that I was afraid of having any one find out. It was in benevolent, unselfish medical lies that I had been dealing, according to the ordinary practice of the medical profession. But as soon as I decided that I could abandon these and need no longer fear that any patient might find out what was being done to him, I had the sense of a weight taken off my shoulders.

ForgetfulnessThere is a very eloquent passage in one of Mrs. Bernard Bosanquet's books2 about social work, in which she describes the psychology of the poorer classes among whom she worked in London, and dwells especially on their characteristic forgetfulness. They cannot learn because they cannot remember. They cannot learn how to avoid mistakes in future because they cannot remember past mistakes. One well-known difference between a feeble-minded person and a person competent to manage the affairs of life, is that the former forgets so extraordinarily, and therefore cannot build up through remembrance of his past how to steer better through the future. Of course we all of us have this disease in varying degrees. We all forget, in the moral field as well as the physical, things that we ought to remember. There are things that we ought to forget. After we have started to jump a fence, we must not remember the possibility of our failing. The time to remember that is before we have begun to jump. Moreover, there is no particular benefit in remembering our own past mistakes if they are such that we cannot do anything about them, morally or any other way.

There are things, then, that we ought to forget, but allowing for these, forgetfulness means forgetting the things which we ought to remember. In alcoholism it is extraordinary how much the person forgets. One cannot fail to be struck by the fact that the alcoholic gets into trouble again and again because he cannot fully remember what happened before. In the field of sex faults this truth is equally obvious. A man is unfaithful to his wife because he allows himself to forget his wife – his memory of her is for the moment blotted out. Nobody could violate his own standards in this field if he could vividly remember them. Hence if we are to help any one else to govern himself in matters of affection we must help him to remember, help him by planning devices that make it nearly impossible to forget.

Bad temper can ordinarily be explained by forgetfulness. We can hardly lose our temper with a person if we remember the other sides of his nature opposed to that with which we are just now about to quarrel. Nobody consists wholly of irritating characteristics. We all possess them; but we all possess something else besides. Hence if we can realize some of our own moments of wrath, I think we must confess that for the moment the person with whom we were enraged possessed for us but a single characteristic. The rest were forgotten.

My account of these five common types of mental deficiency: ignorance, shiftlessness, instability, fears, forgetfulness, is general and vague. I mean to make it so. If my suggestions are of any use to the reader it will be because he is able to make his own specific applications. I want, however, to mention one example of a much more specific fault, namely, nagging. In social work we often see families broken up or seriously cracked by some one's nagging. It consists in reminding people of their defects and shortcomings in season and out of season, until the reminder finally gets upon their nerves. You are aware that your husband, your wife, your child, has some very deleterious fault. Admittedly he has it and it is constantly getting him into trouble. So you want to be quite sure that it never gets him into trouble again; and hence you keep reminding him of it again and again until you produce an irritation that only aggravates the original fault.

Why do I take so trivial and specific a case as this? Because I can remember several cases where I could not possibly leave out nagging when I came to make my social diagnosis. It was one of the chief factors. One cures this disease, in case one does help it at all, by making the nagging person conscious of what it is that he is doing. The nagging impulse is like an itch. It recurs and scratching does not stop it. The nagger does not know quite why he does it; he finds himself doing it almost in his sleep. Hence we try to wake him up, to make him conscious, if we can, of his foolishness, of the kind of harm he is doing, and of the degree of incurability he is inducing in the person whom he is trying to cure.

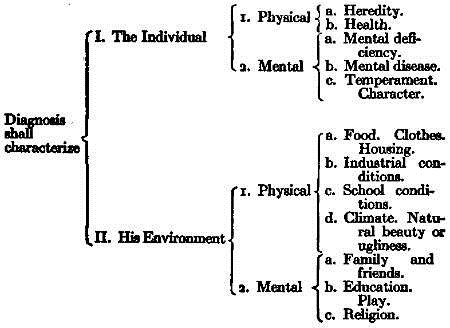

I will now sum up the last four chapters in a diagram which we have used in Boston at the Massachusetts General Hospital to assist us in making our social diagnoses. A social diagnosis can very seldom be made in one word, such as idiocy or tramp. It must include the patient's physical state. It must summarize a person's physical, moral, and economic needs. Our best social diagnoses, such as idiocy or feeble-mindedness, do not refer to the mind only. They refer to the body just as much. Feeble-mindedness is a statement about the child's body, his brain, his voracious appetite, the diseases to which he is likely to succumb, his extraordinary susceptibility to cold, and his poor chances of growing up. One says a great deal about the physical side of a child as soon as one pronounces the word "feeble-minded." Also one says a great deal about his financial future. One knows that the feeble-minded child will never rise beyond a very low point in the economic scale. One says also a great deal about his moral future. We all know to what sexual dangers and temptations he is especially exposed. And on the purely psychological side one can predict his entire unteachability beyond a perfectly definite limit. All this is given in the medical-social diagnosis, "feeble-mindedness."

This is an example, then, of an ideally complete and compact, though a very sad, social diagnosis. It is almost the only good one we have worked out as yet. The only other is "tramp." The tramp in a technical sense is a person who has what the Germans call "Wanderlust." He is unable to stay in one place. Perpetually or periodically he desires to move and to keep moving. The tramp is a medical-social entity. He has certain physical limitations, certain economic limitations, certain moral deficiencies. But in America he is rather a rare being. One does not see many typical tramps here.

Since few social (or medical-social) diagnoses can be stated in a single word, one is usually forced to write down one's diagnosis in a great many different items. As a guide I made four years ago a schedule for our use at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Use – the only test for that sort of thing – has shown this schedule to be of some value.

To make a social diagnosis we should make a summary statement about the individual in his environment. That summary is to include his mental and physical state, and the physical and mental characteristics of his environment. (I here use the word "mental" to include everything that is not physical; that is, to include the moral, the spiritual, every influence that does not come under physics or chemistry.)

When the investigation of a patient is divided between doctor and social worker, the doctor studies his physique; the social worker studies the rest. I believe that there is nothing that we can want to know about any human being, rich or poor, that is not suggested in that schedule. Suppose, reader, that a friend of yours was engaged to be married. Suppose you wanted to know something about the fiancé. You would certainly want to know about his health and his heredity; then what sort of a person he was, his mentality, whether he had any money – what are the obvious physical facts about his environment. To what influences has he been subjected, and what mental supports, such as education and recreation, family, friends, and religion, can he count upon? You would not want to know any more and you ought not to want to know any less.

So in summing up a social diagnosis I think it is convenient to use the four main heads that I have put down here. I think these headings will remind us of everything that we want to put down, and of everything that we may have forgotten to look up. That is one function of such a schedule – to remind us of the things which we have forgotten.

Made up in such a way as this, of course the social diagnosis will have many items, and like medical diagnosis it will be subject to frequent revisions. The doctor who never changes his diagnosis is the doctor who never makes one, or who makes it so elastic that it means nothing. So social workers should never fear to add to, to subtract from or to modify their social diagnoses.

The best medical diagnoses – those made after death – often contain fifteen or twenty items. Before death in a recent case we found pneumonia. After death we found in addition: meningitis, heart-valve disease, kidney trouble, gall-stones, healed tuberculosis, and ten minor troubles in various parts of the body.

So a good social diagnosis will name many misfortunes of mind, body, and estate, healed wounds of the spirit that have left their scar, ossifications, degenerations, contagious crazes which the person has caught, deformities which he has acquired.

CHAPTER VI

THE SOCIAL WORKERS' INVESTIGATION OF FATIGUE, REST, AND INDUSTRIAL DISEASE

Fatigue and restFatigue is more important for medical-social workers to understand than any single matter in physiology or any aspect of the interworkings of the human body and soul, because it comes into almost every case from two sides: (a) from the workers' side because the quality of work that she puts into trying to help somebody else depends on how thoroughly she is rested, and how much she has to give; and (b) from the side of the patient, his physical, economic, and moral troubles, because fatigue is often at or near the root, of all these troubles. It is unfortunate that in spite of its importance, we do not know much about fatigue from the physiological point of view. Since the war of 1914-1918 we have prospects of knowing more about it than ever before; for one of the grains of good saved out of the war's enormous evils has been the fruitful studies of fatigue made in England, studies more valuable than any that I know of.

Let us take fatigue in some of its very simple phases, as it applies to your life and mine. The first thing to recognize is that it can affect any organ; our stomachs can get tired just as well as our legs. When a patient complains of pain, vertigo, nausea, we first ask ourselves, "What disease has he got?" That is correct. Disease must be found if it is there. But the chances are he has no disease, but only a tired stomach, since fatigue easily and frequently affects that organ. When the whole person has been strained by physical, moral, and especially by emotional work, he may give out anywhere. He may give out in his weakest spot, as we say. That weak spot is different in different people. Therefore the study must be individual. We cannot do anything important with our own lives until we learn how and when we get tired. It is the same with people whom we try to help in social work.

Fatigue, then, may be referred to any particular spot in the body. People often go to an oculist to see what is the matter with their eyes, when there is nothing in the world the matter with their eyes: the honest oculist tells them that they are tired, and that for some reason unknown to him their fatigue expresses itself in the eyes.

This is a very common and very misleading fact. The patient finds it hard to believe that medicine ought seldom to be put on the spot where he feels his pain. If the pain is in his stomach he wants some medicine to put in his stomach and not a harangue on his habits, which is usually the only thing we can really do to help him. If he has a pain in his back he wants a plaster or a liniment for his back. It is very hard to get people out of that habit of mind, and we shall surely fail unless we are clear about it ourselves. It must be perfectly clear in our minds, or better, in our own experience, that fatigue may be referred to one spot or to another, in such a way as seriously to mislead us. I suppose that half of all the pains that we try to deal with in a dispensary – and pain, of course, is the commonest of complaints – are not due to any local or organic disease in the part. Doubtless there are some wholly unexplored diseases or disturbances of nutrition in that part, as there may be in the eyes when they ache because you have been walking up a mountain. But medical science knows nothing about that. What we do know is that the pain, if it is to be helped, will be helped not by thinking about that spot or doctoring it, but by trying to get that person rested.

Fatigue, then, ought to be one of our commonest medical-social diagnoses, and to help people out of it, one of the attempts that we most often make. In Dec., 1917, a dozen or more Y.M.C.A. boys consulted me in France, all with coughs, all wanting medicine to stop the cough, and most of them a good deal disappointed because they were told to go home and go to bed, told that they were tired, and that this fact depressed their resistance against bacteria, so that bronchitis or broncho-pneumonia resulted.

The second point, then, that one wants to make about fatigue is, that it is the commonest cause of infectious disease. Pasteur's great discovery, which set modern medicine upon the right bases, sometimes gets twisted out of perspective. Sometimes we fail to realize that the seed may fall upon stony ground. The seed, of course, is bacteria, and its discovery was Pasteur's immense service to humanity. But Pasteur was so busy that he did not emphasize the truth that a seed can fall upon good ground or upon bad ground. When bacteria fall upon bad ground, that is, upon healthy tissue, they do not grow, they do not spring up and multiply. Tired tissues, as has been abundantly proved by animal experimentation, are prone to infection. They are good soil for the growth of bacteria. It is true generally; it is true locally. A part that has been injured, for instance, a part that has been bruised without any break in the skin, without the entrance of any infection from the outside, is damaged by something that hurts its resisting power as fatigue does. Such a part will often become inflamed, will often become subject to the action of bacteria which must have been in the body already, but which had been kept on the frontier by our powers of resistance.

Our "powers of resistance," then, which we cannot more definitely name, which we do not as yet know to be identified with leucocytes or with anything else, can get tired. When they get tired we "catch" a cold or a diarrhea, or a hundred things which seem to have nothing to do with fatigue, but have nevertheless.

Accumulated fatigue or physical debt. If you go up a long flight of steps at a moderate rate, you can get to the top without being tired; if you go up at a rapid rate, as most of us do, you are tired at the top. Physically you put out the same amount of energy, I suppose. I do not see that there can be any considerable difference in the energy consumed by the performance of that act whether we do it slowly or quickly. The difference is that in the first case we rest between each two steps as we rest between each two days at night. When our activities are so balanced as not to run in debt, we rest between each two steps. You and I can walk at our individual peculiar gait on the level for a long time without any accumulation of fatigue, often with refreshment. But push us and we are soon exhausted. Suppose that our normal walking rate is three and a half miles an hour; push us to four, and it may not be a quarter of a mile before we are done up, because we have not been able to avoid accumulated fatigue by resting between each two steps. It has been said that in rowing the crew that wins is the crew that rests between each two strokes. The person who does not get tired is the person who rests between each two days. He does not accumulate fatigue. It is the accumulation that finally breaks you, makes you bankrupt. It is the little unnoticed bit added day by day, week by week, month by month, that makes the break.

Fatigue we should think of as running in debt. One of the figures of speech that has served me best in teaching patients how to live is that figure of income and outgo. I have often said to people, "Physically you are spending more than you earn, not to-day merely, but right along. You must earn more than you spend. You must get a plus balance in the bank. Then you can run along with fatigue or illness."

That figure of speech helps us also to express another fact about fatigue, which is important to recognize in ourselves and in our patients, because otherwise we get thrown off the track: delayed fatigue. The first day that your income begins to be less than your expenditures, nothing necessarily happens. The bank does not proclaim that there is no deposit there. It is some days later, usually, that you begin to reap your troubles. It is the same in physical fatigue. Patients say to us, "I slept ten hours last night. I spent a virtuous Sunday. Why should I be tired to-day?" We should answer, "Because of something you did last Tuesday or thereabouts." We all are familiar with this in relation to sleep. It is not the day after a bad night, but several days later that its effects depress us.

Delayed fatigue, then, is an important thing to notice in ourselves and to bring home to the people that we are trying to help. I suppose one could say that a great part of our business in social work is to call people's attention to things; if they have recognized them before, they will perhaps get a lesson out of what we say. Such matters are referred fatigue, delayed fatigue, accumulated fatigue, – familiar enough, only the person does not act on them because he does not notice them.

The fatigue-rest rhythm, the alternation of fatigue and rest, I have already phrased by the metaphor of earning and spending. You can phrase it also by a metaphor very close to the physical facts as we know them, the metaphor of building up and tearing down. During the daytime, from the point of view of physiology and the workings of the body, we burn up tissue. In us oxidation processes are going on which are really burning, as really as if we saw the flame. Tissue is being destroyed, broken down, going off in the form of heat, energy, and life. That is good in case it is followed, as it should be, by a period of rest in which we build up. Presumably, if we could see with adequate powers of the microscope or powers of observation of some sort, what goes on during rest, we should see a perfect fever of rebuilding all that we have torn down during the day. People often say, "Shall I take exercise?" Yes, but remember that half of the process of taking exercise is getting rested afterwards. It will do you good provided you rest after it, provided what has been torn down in exercise is replaced by sufficient tissue or fresh power in rest.

The English studies of fatigue to which I have referred have been of great importance because, so far as I know, they are the first attempt we have had in the way of testing when men or women in industry are too tired and how much too tired they are. I do not suppose that any employer of labor would want for his own profit or for more than a short time to overwork people in this sense, if he had the facts called to his attention. If he realized what he was doing, he would not want to break down his working force any more than he would to spoil his machinery. But some employers are careful of their steel machinery and careless of their human machinery. They will continue to be so, I fear, until we know more about fatigue.

It is one of the most difficult things to measure that I know. Take it in your own case: what tires you one day does not tire you another day. The individuality of it, the disturbing factors when we try to measure it, are perfectly extraordinary. Such a disturbing factor in our calculations is "second wind" – mental or physical. A number of men marching along will grow less tired as time goes on by the acquisition of what we call "second wind." We do not know what it is. We have tried to connect it with the condition of the heart, to say that the heart finally gets to deal with the volume of blood that is running through it so that there is no overplus of blood stored in any one chamber at any moment. But we do not really know anything about that. We do not know what second wind is; but it is important to know that it exists.

Moreover, as Professor William James pointed out in that essay called "The Energies of Men," there are "mental second winds." Just when a man is worn out he often finds new strength. He often cannot get his best strength until he pushes himself even to despair. In the spiritual experiences of the world's saints and heroes we find that it was just when it seemed as if they were about to go under that this second wind, or third wind, for it sometimes comes again and again, this mitigation of fatigue without rest, comes to them. This is a most disturbing fact. If we were like a pitcher which is emptied out and filled up, we should know all about fatigue very soon. We are like a pitcher to a certain extent, but the similarity is disturbed by such factors as second wind, and disturbed, moreover, by mental and emotional intruders like music. A military band coming upon a body of marching men will give them strength when they had no strength. That is not a sentimental but a practical fact which army men have to take advantage of. Then the fact that many people can rest by change of work without stopping, is also disconcerting. We say to a person, "You have been working hard all day; you must stop, lie down, go to bed." That person disobeys, keeps going on something different, is altogether fresh next morning, and we have to confess that we were wrong.

It is a very familiar experience that one may be almost dead from one point of view, but quite fresh from another, as one wants no more meat, but has plenty of room for dessert. Some people can rest by change of work and some cannot. It is very important for us to keep finding out in a great number of ways which of the classes into which people's bodies are divided we each belong to. Do we belong in the class of the people who must get their rest by giving up, by the abolition of all function, or in the class who rest by the change of function, by doing something different from the day's work? It is a question of fact and must be found out by each individual for himself.