полная версия

полная версияPrivate Journal of Henry Francis Brooke

July 6th.– I was up at 4 a.m. and out at ½ past 4, and set off across country to catch up the Brigade and ride a few miles with them, and then come home. They, however, had started at 4 o'clock also, and so I did not come up with them till they were 12 miles from Kandahar, which was not to be wondered at, as they had 6 miles start of me, and got off half an hour earlier than I did. I could not, therefore (as I had to be back for breakfast and work), go very much further with them, so, after seeing them on their way a mile or so further, I struck off through new country and went straight for Camp, which I reached at nine o'clock. I rode Rufus, who did his 27 miles in first-class style, and could have done half as many more without any trouble. The morning was cool, almost cold, and a good deal of the country very pretty. The climate just now, and the excellent forage we get, suits the horses very well, and they are all, both public and private, in first-class order.

July 7th.– Nothing of interest, except that we had news from Kelat-i-Ghilzi that they had a small skirmish there on the 1st July. The news made me more than ever disappointed that I did not get off to visit that place as was originally intended, as I should then have been in for this affair.

July 8th.– Rode a long way up the Argandab Valley this morning in hopes of picking up some information, or ascertaining if there were any signs of movement or excitement. Everything seemed very quiet, and the people in the numerous villages I rode through were very busy thrashing their corn. An absurd accident happened to me as I was riding home, which at one time threatened, though quite free from any danger to myself, to effect the destruction of my one pair of long riding boots, which would have been an irreparable disaster. I had to ford a small water channel about 6 or 7 yards wide, the water of which was muddy, but looked quite shallow, so I rode in very carelessly, but had not gone 2 yards when Mr. Akhbar went right down over his saddle, plunging violently. He managed to get his chest on the bank, and I lost no time in springing on to hard ground and hauling him, with some difficulty, out of the hole, nothing the worse, I am glad to say. It appears that the people had dug a well about 10 feet deep in the bed of the water-course, and it was into this we had got. Of course I was wet through, and so was the saddle, but the sun was warm, and I was an hour and a half from home, and long before I arrived there everything was dry. I had to take my poor boots off most gingerly, and have been nursing them greatly, and I think they are nothing the worse. I was much more anxious about them than anything else, as nothing of the kind is to be got here, and parcels take 2 and 3 months coming up from Bombay. I am beginning to get rather short of clothes, as it was a great loss having all the contents of my portmanteau, which were principally strong warm clothes, looted on the way up here. The orchards of peaches and nectarines in the Argandab Valley are just now quite beautiful to look at. The trees are loaded with most splendid looking fruit, which, however, are rather disappointing when picked, as they don't seem to ripen thoroughly.

July 9th.– We had an unofficial rumour that the advance guard of the Wāli's army had been met at Washir by the Cavalry of Ayoub Khan's army and defeated, but as no confirmation of the rumour has come from General Burrows, we are not inclined to credit it, though it is received as quite true by the people in the city, who are only too glad to believe anything to the detriment of the Wāli. Of course we must expect all sorts of rumours now, and I am, for curiosity, writing them all down as we get them to see how many eventually prove true, and how many are incorrect.

Chief of Kokaran deserted the WāliJuly 10th.– To-day it was reported that considerable disaffection exists among the Wāli's Chiefs and Officers, and that the most important man of the lot, the Chief of Kokaran, a place about 6 miles from this, has deserted, and this – July 11th – was so far confirmed that we received official news that he had, with 80 followers, withdrawn himself from the Wāli's force, although it does not appear, so far, that he has joined Ayoub Khan. In accordance with Afghan customs, the Wāli's representatives here at once took reprisals by seizing the son of the Chief of Kokaran (a small boy in a bad state of health) and putting him in prison, and taking possession of the house and property of the deserter at Kokaran.

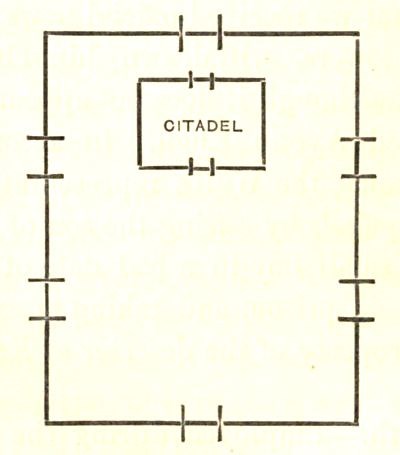

July 12th.– Employed during the morning in endeavouring to make arrangements for making the Citadel safer and more in accordance with the rules of war, but the task is hopeless, as the place is radically bad in a military point of view, and surrounded with houses on 3 sides. Strictly speaking these houses should have been knocked down for at least 300 yards all round the wall of the Citadel, but General Stewart appears to have set his face against any military precautions, insisting that they were quite unnecessary, "as the people were friendly to us." The consequence is that the whole position here is, strictly speaking, untenable – that is, if an enemy with either organization or means were to come against it. As, however, there is no possibility of any scientific attack being made on us, we feel that, bad as the position is, we can quite engage to hold it, and lick the enemy outside into the bargain. The City of Kandahar is a parallelogram about 1¼ miles long, and ¾ of a mile wide, something like this —

The Citadel is close to the north end, and the outer wall of the City forms then a sort of double wall to the Citadel.

There are 6 gates in the wall of the City, which is fully 20 to 30 feet high, and very thick and strong. At each of the city gates there is a guard of Native Infantry, and we hold the keys of the gates which we lock every night at sunset, after which hour neither entrance nor exit is permitted to anyone. The guards are stationed on the ramparts, and their posts should, from the first, according to the most ordinary rules of war, have been put in a state of defence, but nothing was done to them, and General Primrose has been unwilling to make a change in the matter. Now, however, he has allowed me to take measures to make them safe in the event of any outbreak.

Rumoured advance of Ayoub KhanJuly 13.– A welcome addition to our force reached us to-day, in the shape of the Head Qrs. Wing of the 4th N.I., which marched in from Quetta. The remainder of the regiment will follow shortly. There was a report that Ayoub Khan, with his army, had actually left Furrah, and that his advance guard was at Washir, but there is no confirmation of the collision between his and the Wāli's forces there, which has probably never occurred. There is much excitement in the city, and the merchants, jewellers, &c., are hiding and burying their property, which means, I assume, that they don't believe in our power to defend the city against Ayoub Khan. A gathering of the enemy is reported as being at Karkrez, about 30 miles off, and there is much excitement among the tribes in the Arghastan Valley. There is no doubt it is very desirable that our force at Girishk should have an opportunity of administering a lesson to some one, or we shall probably have to do something in that way ourselves here.

July 14th.– Information received that one of the Wāli's regiments, composed of men from Kabul, is mutinous. They are in the fort of Girishk with the Wāli. Ayoub Khan is said to have with him 1,800 cavalry and 4,000 infantry, and 30 guns. So General Burrows' force of 2,500 men and 6 guns have not much to fear. I visited all the guards on the city gates in the evening, and walked round the whole city on the ramparts, and had a good view of the inhabitants preparing to go to bed on the roofs of their houses, which are flat, and always used as the sleeping apartments of the family. The ramparts are 20 to 25 feet high, and as the houses are all one-storied, the roofs were much below us, and we saw more of Afghan domestic life than usual, as the people did not anticipate that anyone would be passing round then, and the roofs were covered with ladies, who, however, very quickly let down their veils when they saw us in the distance.

Guns recovered from mutinous troopsJuly 15.– News from General Burrows received this morning states, that the whole of the Wāli's army was mutinous, and that the situation was so critical that he had decided it was necessary he should disregard the positive orders he had received not to cross the Helmund, and that he proposed to do so, and disarm the mutineers. I should explain that our force is, under orders from the Viceroy, halted on the Kandahar side of the Helmund, while the Wāli and his army are in the fort of Girishk, which is on the Herat side of the Helmund. Later in the day news arrived from the Wāli (which was apparently authentic), that early the previous morning (14th) the whole of his army left him, taking with them the Battery of guns our Government had been so idiotic as to give the Wāli. The letter, which was from the Wāli to his son, who is here, went on to say, that immediately General Burrows heard this, he had crossed the river with his cavalry and Horse artillery, and pursued the mutineers, and coming up with them had killed 200 and recovered the guns. This report seems authentic, though probably exaggerated, but as yet no confirmation has been received from General Burrows. True or not, the report has had a good effect in the city, and will help to show that the people are not likely to improve matters by trying conclusions with us. I had a deputation from the Parsee shopkeepers, who have followed the army from India, and have shops in our camp, where they sell us wine and provisions, &c., at most exorbitant rates, to beg me to give them a place in the fort for their stores, as they were in a dreadful fright for their lives and their property. Even if I had considered they were in danger, I would not have acceded to their request, as I would much prefer their running certain risks, to giving public confidence the shock of supposing I thought it necessary for our camp followers to take refuge in the fort, so I laughed at their fears, refused their petition, and comforted them by saying, that even if they now lost the whole contents of their shops, they would still be great gainers, as they have made their fortunes already by swindling us. They did not seem to see this in the light I did, but had to accept the inevitable, and take their share of the risks. As there is a large number of evilly-disposed men in the city, it was decided that it was desirable to show |40-pounder guns moved into fort.| them we were determined to put down any disturbances with a strong hand, so we moved down two of our 40 pounder guns into the fort, and placed them in position to shell the city, and at the same time established a system of strong patrols, which night and day visit the city, and go through all the main streets. There is no denying these patrols would be in an unpleasant position if attacked, as street fighting is, of all, the most disagreeable, but I have given clear and distinct orders for the guidance of the officers in command, from which they learn what they are expected to do, and which will cover their responsibility in resorting, if necessary, to strong measures. The great objection one feels to returning a fire in a street is, that in such cases it is always unfortunate children and women who suffer, and not the men who deserve it, and who take precious good care to remain under cover. I visited the city myself, and found all quiet, and went with the Wāli's chief man to arrange for certain improvement to the fortifications, and was quite civilly received everywhere. It was satisfactory to find that already the arrival of the guns in the fort was known and appreciated, and one Afghan said to me, "They" (the guns) "are very big: two discharges from them and the city would be destroyed." I answered in the language of the country, "I believe you, my boy."

July 16th.– Rode out to Kokeran, and on arrival there, met a well armed caravan, the people composing which could give but an unsatisfactory account of themselves, so one of our native cavalry patrols coming up at the moment, I made the lot prisoners, and sent them into the city to be examined. They may only be peaceful traders armed for their own defence, as they were perfectly civil, but even in that case some information will be got out of them. No news yet from General Burrows, who possibly has gone on in hopes of meeting Ayoub Khan. We have decided to disarm every Afghan approaching Kandahar, and I have issued the necessary orders to ensure this being done.

July 16th.– Rode out to Kokeran in the morning, returning by the Argandab, all seemed quiet. Visited the city in the evening, and found all quiet there also.

July 17th.– Was woke at 2·30 a.m. by the Brigade-Major bringing the officer commanding the cavalry patrol (which is on duty round the camp all night), who reported that a considerable fire was burning in the direction of Kokeran. As these fires very often indicate a collection of men bent on mischief, I desired him to proceed cautiously with his patrol in the direction of the fire, and ascertain its cause, and bring me information, and at the same time I ordered a troop of cavalry to follow in support. The fire proved to be caused by some evilly-disposed persons having set a light to the corn and straw stacks of a peaceably-disposed native, living some 8 or 9 miles from camp, and the patrol found no signs of a gathering of men, so returned to camp. Confirmation was received from General Burrows of his successful fight at Girishk against our supposed friends, the troops of the Wāli, in which he had succeeded in recovering the Battery of artillery which our Government had given as a present to the Wāli, and the first time it was used was to fire upon us! General Burrows also recovered a great deal of stores and baggage belonging to the Wāli, and much ammunition, and on the whole made a very successful business, losing but very few men himself, the loss of the enemy being computed by themselves at 400, but was probably not more than half that number. There being a want of supplies at Girishk, General |Retrograde movement on Kushki-Nakud.| Burrows thought it right to fall back to a place 25 miles nearer to Kandahar, called Kushki-Nakud. There were many good reasons, I confess, for this move, but personally I would never willingly, in Eastern warfare, take a retrograde step, except under the strongest compulsion, as Afghans know nothing, and care less, about the laws of strategy, and see only defeat in any but forward movements. The fact is, had we known that the Wāli's army intended to mutiny, we would never have advanced beyond Kushki-Nakud, as there are many good objections to the position at Girishk. That we did not know the shaky state of the Wāli's troops is all the fault of the Political officer with the Wāli, who, wishing to see all things couleur de rose, persuaded himself that all was right, and could not, or would not, believe any evil of them. Even he must now see what we have felt sure of all along, that Shere Ali is quite without power or influence, and quite unable to maintain his own authority for a day without our assistance. We have, of course, here, the reflex of the events at Girishk, as there has been a very marked increase of excitement and turbulence in the city, since the news of the mutiny of the Wāli's troops has arrived, and had not, at the same time, the intelligence of the licking they had received from us reached the city, we should certainly have had an outbreak there.

July 18th.– Moved another 40 pounder gun into the fort, and mounted it on a very commanding position, from which we could soon destroy the best part of the city. Of course there is no intention of a measure of this kind, but a big gun ready for action has a very soothing effect on the warlike feelings of Afghans, or Easterns generally. Intelligence was brought in, that attacks on the posts of Mandi Hissar and Abdul Rahmon were likely, and though it was not thought there was much chance of these places, which are now very fairly strong, being attacked, it was thought wise to send some cavalry to reconnoitre, which was done; but the officer, on arrival at Abdul Rahmon (25 miles off), was able to telegraph that all was quiet and no sign of gatherings or excitement. If, however, the existing state of feeling in the country grows or becomes intensified, it is quite possible these posts may be attacked, but if so they should be well able to hold their own.

Cavalry patrol fired upon – officer woundedJuly 19th.– Was suddenly woke at 2 a.m. by the sound of a volley of musketry close to our quarters, followed by the noise of horses galloping. I at once recognised what had happened – indeed it was the only thing which could have happened – that the cavalry patrol had been fired on by some of the enemy. I lost no time in getting to the best place for a view, and presently one of the patrol rode up and reported that as they had been passing along, about 200 yards from our quarters, a volley had been fired into them from behind a low wall, and that several men and horses had been hit. I immediately sent off orders for 2 companies of the 7th Fusiliers and a troop of cavalry to turn out, and getting dressed as quickly as possible, was mounted and ready before the troops could come. We then carefully swept the whole ground round the camp, but of course failed to find the attackers, although we certainly were on their track ten minutes after they had fired. The country round our camp lends itself in the most unsatisfactory manner to small attacks of this kind, as on all sides there are enormous cemeteries, with thousands of graves and vaults, into any of which a few men could get and hide with absolute safety. The night was dark, the moon having set, and a haze come up, as it generally does here towards morning. On investigation I found that the native officer commanding the patrol was badly wounded in the arm, and that 2 horses were slightly wounded, and one soldier and one horse were killed. While I and the Brigade-Major, and the Cavalry Colonel, were standing together, near the man who was killed, an intelligent? native sentry who was posted about 400 yards off, took it into his wise head to decide that we were a party of the enemy, and putting a bullet into his rifle, took a deliberate and, I must say, extremely good shot at us, aiming, I am glad to say, just a few feet too high. I had not heard the whiz of a rifle bullet since the China days, but I had no difficulty in recognizing it again, and as soon as weightier matters allowed, I had my friend, the sentry, made a prisoner of, and properly punished the next morning. All things considered, we have had very little wild firing by sentries here, but, as is always the case, there have been some few instances which I have not failed to punish without accepting any excuses. This little affair of the patrol is another excellent instance of how little Sir Donald Stewart did to make the position here as good in a military sense as it could be – as had he done so, he would not have left a wall or enclosure standing within a thousand yards of our camp anywhere. He, however, would have none of them touched, first because he wanted to conciliate the people; and next, because he wanted to save the expense of pulling them down. When General Primrose came he accepted the existing state of affairs, and would allow nothing to be done, although General Burrows and I naturally have wished to have things more ship-shape. I lost no time in pointing a moral, and adorning a tale after the affair of the patrol, and got permission to take down all walls and enclosures in the immediate vicinity of the Barracks, of which permission I have availed myself to the full, and a little over, and made a very perceptible improvement, though I am by no means contented yet. I asked General Primrose to insist on the Wāli's people levelling various big enclosures between our position and the city walls, but as they surround very holy shrines and mosques, they begged for a respite on promise of good behaviour, and I am sorry to say it has been granted. However, what has been done is most useful, and makes the work of the patrols easier and safer. It was very unfortunate that the native officer commanding the patrol should have been shot in the right arm, and his horse wounded, as he was unable to pull up the horse for some distance, and so did not succeed in seeing where the men who attacked him went to.

Daily visits into city – all quietJuly 20th.– Paid my usual visit to the city, and found all very quiet, and the people by no means uncivil. In the evening I took all the cavalry officers, English and native, round the camp, and gave them my ideas of the way in which they should patrol, and what a patrol should do when fired on (i. e., not run away).

July 21.– Having arranged with Major Adam, the Assistant Quartermaster-General, to make a reconnaisance through the villages in the Argandab, we started from camp at half-past 4 o'clock (a lovely fresh morning), and, crossing the Baba-i-Wali Pass, rode for several miles up the Valley as far as a village called Sardeh Bala. – (N.B. – You will find all these places on the big map I sent you last mail, which will give you a capital idea of the events I have now to tell of). Turning back from there we proposed to return into the Kandahar plain by the pass across the range of hills (which separates the plain from the Argandab Valley) which is called the Kotal-i-Murcha. This range of hills, which is very clearly marked on the big map, rises to a considerable height, being often as much as 2,000 to 2,500 feet above the plain. The two passes through the range are the Baba-i-Wali and the Kotal-i-Murcha. The first is passable by men and horses, and we have made a road for guns over it. The second is a mere mountain track, up which not more than one man can go abreast, and part of which is so strewn with detached rocks that it is absolutely necessary to dismount and lead a horse along it. This pass, however, is a short cut from the city into the Argandab, and we have all used it regularly when riding out there. I myself rode that way on the 16th, and there was, therefore, nothing rash or unwise in our returning that way. From the commencement of the ascent to the top of the pass is about ½ a mile, and the rise in that distance is 700 to 800 feet, and therefore very steep. We had just commenced the ascent when one of our escort drew our attention to some men dodging behind the rocks over our head, who had guns, and were evidently trying to avoid being seen. An armed man is so usual a sight in this country that I did not for the moment think anything of the matter, and indeed prevented Major Adam, who said he would like to take a shot at the nearest man from doing so. As a precaution, however, I ordered 3 of the escort to dismount and get out their carbines, and Major Adam took a carbine, and so did I, and we slowly ascended, keeping our eye on our friends, or rather on the place they had been, for we could not see them then. Presently (all this occurred in less time than I write it) we saw one scoundrel pop his head up from behind a stone and take aim. We were too |Fired upon in Kotal-i-Murcha pass.| quick for him, for Major Adam and one of the escort let fly at him, and so threw out his aim, that he fired high, and no one was touched. Immediately, however, 3 more shots were fired, one killing one of the horses of the escort, our fire in return being quite harmless, as our assailants were behind rocks, and we were out in the open. Still it served to unsteady their aim, and we got to the top and under cover without further damage, though most of the shots had been fairly well directed for us. I had one shot as I came up, which, I am sorry to say, was not successful, though I made my friend "leave that," as Paddy Roe used to say when I fired at a hare and, according to my custom, missed it. As soon as I got the party under cover I sent men down on each side of the hill (having first sent off to Kandahar, 4½ miles off, for 20 infantry to help in the hunt through the rocks) to prevent the enemy getting down and running away, and Major Adam and I, each with 2 men and a pocketful of ammunition, essayed climbing the hill. He first descended a good bit and hit off a fairish path which took him a long way up, and during the ascent he had 4 or 5 shots, but never could get near the fellows at all, they being all mountaineers, and we being burdened with heavy riding boots, spurs, &c., and knowing nothing of the paths. I, with my two men, made excellent progress at first, but found ourselves regularly stuck on the top of a precipice, across which, at about 300 yards, we could see one of the men making off. I took, as I thought, very good aim, making one of the men with me fire too, but we again missed, whereupon the runaway turned round and let fly at us, but expecting this we were safely behind a rock, and I don't think his bullet came near us. I had then to descend, and before I could hit off another path, the whole lot were out of sight. It was dreadfully hot, and we were dying of thirst, and not a drop of water within 3 miles, but of course had to stay until the infantry came. I sent off one of my two men to Kandahar with news to tell them the direction the enemy had run in, and I and the other man comfortably behind a good rock with our carbines ready, waited in hopes of getting a better shot, but never saw our assailants again. In due course first some cavalry, and then, after a considerable interval, some infantry came out to me, and we hunted the hill, but it was so precipitous and so full of caves that our search was without result. I did not, of course, accompany this party as I wanted to get back to camp, and besides was nearly dead with thirst. I cannot, I fear, give a good idea of the difficulties of climbing or searching this range of hills which are nothing but limestone rocks, not a tree, blade of grass, or inch of earth on them, so one might as well be trying to climb the cliffs at Bundoran, only that these hills are much higher. I dare say you will think it was a good deal of trouble and time to spend over a small party of marauders of this kind, and so it was, but my reason was that I was anxious to impress by practice what I have so often preached, the necessity for officers and men on such occasions as this always trying to give as good as they get, and not considering they had done their duty when they followed the example of Captain Carey and others by galloping away as fast as they could. With this object in view, I don't think I was wrong to turn myself for an hour or so into a private soldier, and do a little skirmishing on foot with a carbine. We had eight men of the Native Cavalry with us, and they were as staunch as steel |Attack exaggerated by messengers sent.| and very quiet and cool, except the 2 men who I sent into Kandahar with the order to send me out help, which order I wrote, and in a most guarded way, saying "I want 20 infantry, and a few cavalry as scouts." However, once away from the influence of the officers, the imagination of my orderlies magnified the whole affair, and as they rode through the camp they told every one that the General Sahib had been fired at and was engaged in a great battle with thousands of the enemy who were pressing on to Kandahar. This, unfortunately, was believed, and all the troops were turned out, and a regular commotion got up in the city, and altogether a very objectionable state of alarm was arrived at. When I came in and heard of it, I gave all concerned a lecture which they won't forget, for if there is one thing I hate more than another it is false alarms, and so far I have not had one. And now I must defend myself against the idea everyone seems to have that I go about here rashly, as I really do not, as I always have my escort, and till the last ten days it was quite safe to move about, and in this particular instance it never for a moment entered Major Adam's or my mind that there was the slightest risk going over the Murcha Pass. Had we thought so we would have avoided it, but once being in the business there was only one thing for us to do, and that was to see it through. Lots of men, women, and children had crossed the pass that morning, and we had met them and spoken to them. My rides are now much circumscribed, and I don't think just at present of going any distance from camp merely for amusement. Yesterday we went on business, and with what is considered, and what proved to be, a quite sufficient escort. I was riding my white horse, Selim, and he behaved like an angel, and took no notice of the firing, and when I had to dismount at the bad piece of the pass, followed me up without any difficulty. Afterwards I fastened him to a stone, and he stood quite quietly there for 4 hours without giving any trouble. I did not get in till ½ past one, very thirsty, very hungry, and very hot, but this kind of work never does me any harm, and I was as fit as possible as soon as I had a bath and my breakfast.