полная версия

полная версияPrivate Journal of Henry Francis Brooke

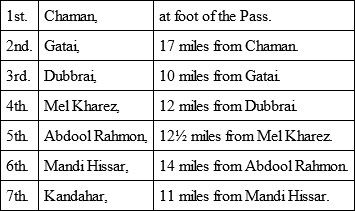

Sunday, April 18th.– Before continuing my story it will be as well to explain that between the Khojak Pass and Kandahar, the road is divided into 6 stages, as follows: —

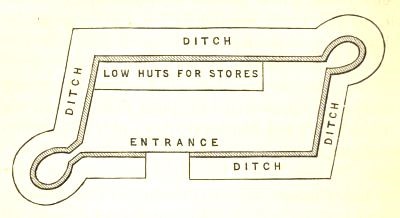

At each of these places there is a small enclosure, it cannot be called a fort, in which the commissariat stores are placed. General Stewart refused to garrison the smaller of these with our troops, but left them in charge of native levies who the civil authorities assured him were perfectly trustworthy. The value of this opinion has been very conclusively shown by the events of the past week. Each enclosure or fort is like the other, except in size, some being larger than others. They are of the following shape: —

General Phayre (leaving me, however, full powers to act as I thought best) suggested to me that it would be better to wait at Gatai till the guns and the European troops reached me, but on reflection I came to the conclusion that to leave Dubbrai unoccupied, and the dead unburied a moment longer than could be avoided, would have the worst effect, and that it was quite worth risking something to obviate this, so, as soon as it was light, I issued orders (I may mention for my soldier and sailor brothers' information that I have throughout given each person distinct and plain written orders, so that everyone knew exactly what to do, and once I issued an order I never changed it) for reconnoitering parties of cavalry to proceed to Dubbrai and the hills to our right front, while I pushed on a detachment of native infantry, with a few cavalry, to re-occupy Dubbrai. I, of course, left a sufficient force at Gatai to hold it, instructing the officer in command to strengthen the defences and keep a good look out. I did not, I confess, expect opposition, and was not therefore surprised to find, when I followed the main body with a small cavalry escort, that they had found Dubbrai empty, except of dead bodies, and seen none of the enemy on the road. We found in and around the Fort 30 dead bodies and 1 wounded man, who told us he was a Ghazi (fanatic), from Khelat-i-Ghilzi, and that there were plenty more of them coming. The men were most anxious to shoot the wretched creature, and I think the officers generally thought it would have been right to do so, but of course I forbid anything of the kind, and ordered him medical aid, and such food and drink as we had at our disposal. I am bound to say he was not a bit grateful, but regularly spit at us and defied us. He died the next day, which was quite the best thing he could |Account of the Dubbrai Attack.| have done. Among the dead we found and recognized poor Major Waudby's body, which I buried near the place he fell, reading the funeral service myself as the best and greatest mark of respect I, as commanding the force, could give to as gallant a soldier as ever lived. Poor fellow, he had warning full 8 hours before the attack, and could easily have evacuated the place, but knowing the country and natives well, he knew what an evil effect it would have if it was known a Sahib had shown fear, and so he clearly elected to accept, one may say, certain death, rather than discredit his name. He had only 2 sepoys of his own regiment with him, all the rest being helpless unarmed servants of his own and the commissariat establishment. He must have fought splendidly, as the enemy themselves acknowledge that they had 16 killed and 18 wounded, which was very good shooting. Nearly everyone we saw of the enemy was shot right through the head, so poor Waudby must have been as cool and collected as if he had been shooting pheasants. His 2 sepoys died with him, and were found beside him. We also found his dog sitting by his body refusing to be moved. The poor dog had 2 terrible sword cuts on his back, but is recovering, and will be sent home to Mrs. Waudby. While at Dubbrai I received a despatch from Kandahar, saying that they had sent out troops from there to open the road up to wherever they met us, and the officer in command sent me word that no resistance had been offered and I could march on in the ordinary way. I at once sent back to Chaman and countermanded the move of the guns, and gave the necessary orders for the improving of the defences of Dubbrai, and at the same time wrote to Kandahar to General Primrose, recommending that I should remain a few days in the neighbourhood with a force of cavalry, artillery and infantry, and that I should march through all the disaffected districts, as I believed this course necessary and desirable. I then rode back to Gatai, on my way going to see about the removal into safety |Await orders – return to Gatai.| at that place of a large quantity of Government property which one of my patrolling parties had discovered in the middle of some hills about half way between the two places. These things proved to be a large convoy of Government stores which an Afghan contractor had been bringing upon camels to Kandahar, when he was attacked by the enemy, and obliged to drop his load, and give them his camels to carry the wounded and the loot from Dubbrai. We succeeded in rescuing them and bringing them into the fort at Gatai, where I was obliged to leave them.

April 19th.– The next morning I was reinforced by some of the 7th Fusiliers, my own escort with my baggage coming in at the same time. I had been 48 hours without anything but the clothes I stood in, and I must say I really felt very little inconvenience from the want of my luxuries. The ground does not make half a bad bed, especially if one has been riding in a hot sun for 12 or 14 hours, and as to eating and drinking there is no sauce like hunger and thirst, and under such circumstances it is wonderful how extremely nice, things, that really are very nasty, seem. I have discovered that a saddle is a first-class pillow, and that with it and a couple of blankets and a fairly soft piece of ground, a most excellent bed is quite possible. The truth was, I was really done when evening came, and any place where one could stretch oneself was delightful. On the afternoon of the 19th I rode back to Dubbrai to try to telegraph to Kandahar, taking a telegraph signaller with his instrument with me. The enemy had again (after all my trouble of the previous day) cut the wire, and we had a lot more work to do so very unwillingly, as it was getting dark, and I had only 2 native cavalry soldiers with me and no officer, I was obliged to start back to Gatai without succeeding in sending my telegram. It was rather a risky ride back in the dark (I did not get back into camp till near 9 o'clock), but I kept a good look out, and always took care to be going rather hard in any confined place where the enemy could have concealed themselves. We saw not a soul, except on one occasion in an open piece of ground, I thought I made out 4 or 5 fellows about a quarter of a mile off, who, the very instant they saw I was coming towards them with my 2 soldiers, bolted, and I thought, under the circumstances, that I had no business to go skying after them, so pursued my road quietly without an accident or incident of any kind.

April 20th.– This morning the wire was restored, and General Primrose telegraphed to me that it was not thought necessary to keep troops, as I suggested, at Gatai and thereabouts, and that he wanted me at Kandahar. I then thought this wrong, and still think so, and the events of the last few days have amply supported my views. However, I had nothing to do but to obey, which I did, stating, however, my views of the position very plainly in my report. The 7th Fusiliers (Head Quarters) joined me this morning full of indignation because one of their native servants, who had strayed away from the road, had been attacked by Afghans and most seriously wounded. They had sent a couple of cavalry soldiers out, who had evidently seized the first two Afghans they had met and declared them to be the culprits. There was a great demand for immediate justice? and I fancy the lives of the 2 poor wretches would not have been worth much had I not been in camp and positively prohibited anything but an enquiry, leaving the punishment of the men to the Civil authorities. I was the more determined on this point, as the evidence against them seemed to me to be very weak. |March to Mel Kharez.| I marched for Mel Kharez at 4 o'clock with my usual escort and party, and stopping to dine at Dubbrai, arrived at the end of our journey (the distance is 21 miles) about half-past 11. The last 2 hours we had a bright moon and clear cold air, and the ride was very enjoyable.

Wednesday, 21st April.– Mel Kharez has a Fort like the other places, and it was also looted, but no English officer being there, the native Commissariat Establishment had very wisely bolted to safety, and so no one was killed. I should say that this station was, of course, more favorably situated than Dubbrai, as it was within 12 miles of a military post of ours, while Dubbrai was at least 25 miles away from any help. I forgot to mention an amusing little incident at Gatai. There also the Commissariat agent, a Parsee, had run away when the place was attacked. When he returned and came to me to report his arrival, I said to him in chaff, "oh, you are the gentleman who ran away!" to which he replied quite as if he was much pleased with himself, "yes, sir, I ran away, and thereby I have saved my life," which was certainly true. At Gatai I had much trouble in getting water, the neighbouring chiefs having cut off the stream which supplied the Fort. After exhausting all gentle means to bring them to reason, I tried the moral force of some cavalry who I sent with orders to bring the chief man before me. The officer did his work capitally, bringing back a leading native chief, whose seizure had the best effect, as the water flowed into our camp sharp enough as soon as they knew I had their head man in my power. I kept my friend as a kind of a state prisoner till the next morning, when, with the usual formalities of Eastern life, I gave him an interview. He was a singularly handsome fine old man, with (like all true Afghans) a very Jewish type of countenance and a good manner. He was humble enough, and tried to make all sorts of excuses, none of which I informed him I thought at all good, but as the water had been turned on, and he had apologised for the delay, I dismissed him with a warning for the future. Several of the other chiefs came in to make their salaam to me, and to promise all sorts of things for the future. An Afghan is, however, so natural a liar that no one thinks of believing them, and among themselves they are never weak enough to put any trust one in the other, and in this they are quite wise, as a more treacherous lying set of beings do not, I suppose, exist on the face of the |March to Abdool Rahmon.| world. We marched from Mel Kharez at 2 p.m., a beautiful afternoon, to Abdool Rahmon, which is 12½ miles off. The road lay through an undulating valley, on the edges of which there were some signs of cultivation. Four miles from Mel Kharez is a range of hills called the Ghlo Kotal, at which we had hoped and expected the enemy would have made a stand, but they had bolted on the first sign of our troops approaching. After crossing the Kotal we descended into the Takt-i-Pul plain, and reached Abdool Rahmon about 6 o'clock. There is the usual Fort at this place, and it is well and sufficiently garrisoned, and its defences are quite good enough for the requirements. Abdool Rahmon is 26 miles from Kandahar, so I determined I would ride in there ahead of my party next morning, leaving them with the baggage to do the distance in the usual 2 marches. I got the native chief of the place, a certain Gholām Jan, to lend me a trotting camel on which to send my bag and bedding into Kandahar, and arranged to ride Rufus the first stage and a cavalry horse the last one into Kandahar. An order from Kandahar prohibits officers attempting to go alone, so I took an escort of a non-commissioned officer and 4 cavalry soldiers with me, the escort being relieved at the next stage.

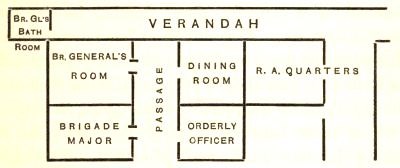

Thursday, 22nd April.– Left Abdool Rahmon at 6.30 a.m., with an escort of 5 sowars (native cavalry), and cantered to Mandi Hissar, the next and last stage on the road to Kandahar. The country is a dead plain, with some little cultivation, and intersected by watercourses. There are numerous fortified villages dotted about, from which the passers by are very often fired upon. At Mandi Hissar I was to change my horse for a trooper from the cavalry detachment there, and also to relieve my escort. While the horse and escort were being prepared I had a talk with the old Soubadar (native captain) commanding the detachment of the 19th Native infantry quartered there, who, with all his men, were most anxious to hear all I could tell them about Major Waudby, who was beloved by all in the regiment. The old Soubadar told me that they all knew what a big heart (i. e., how brave) he had, and he added "if we can only meet the Afghan scoundrels, we will avenge Waudby Sahib's death right well;" and so I feel sure they will. To show the feeling of this regiment I may mention that when the news of Major Waudby's death was received, a detachment of 150 men were ordered to march at once to join me. The men were told off in the usual manner, but when the detachment paraded it was found that 170 were present, 20 men having fallen in in the hopes that they would not be discovered, and would succeed in getting to the front. After leaving Mandi Hissar, the country is the usual stony, dusty desert for 3 or 4 miles, when a low range of hills are crossed, |First glimpse of Kandahar.| and the road descends into the valley in which Kandahar lies, which was green with corn fields and orchards, and was the pleasantest sight I had seen since I left Bombay. In the distance the grey mud walls of the city of Kandahar were visible, but making no imposing appearance, and differing really in no way from the villages we had passed, except the extent was greater, and that in many places the line of the walls was hidden by the orchards which lie all round the city. Unlike most Mahomedan cities, no domes or minarets of mosques were visible, and I believe there is in the whole place but one mosque of any importance, and it would be hardly noticed in any Mahomedan town in India. Passing round the wall of the city I was conducted by an orderly who had been sent out to meet me to the charming house in which General Primrose and his staff live, where I found a very friendly welcome, and a very good breakfast ready for me. Including a quarter of an hour's halt at Mandi Hissar, I had accomplished my ride of 25 miles in 3½ hours, which was sufficiently fast, as I did not want to over-ride my horses. The house occupied by the General is a regular native building, composed of small and oddly shaped rooms, very thick walls, and a flat roof. Many of the rooms are highly ornamented with painting and gilding, and it is a quaint and cool place to live in, especially as it stands in a delightful garden full of roses, mulberries, peach, pear, plum trees, and vines, through which flow narrow canals of water with a rapid stream, and forms altogether a most delightfully quiet and refreshing sight after the wretched deserts we had been passing through. In this garden, but in another house, also lives the chief political officer, Colonel St. John, and his assistant. The garden has a wall 12 feet high round it, and the entrances are guarded by English native troops, as it is, of course, important to avoid any risks to the chief military officer. Outside the garden lie the very regiments of the force, for the greater number of whom a certain degree of shelter from the sun is provided in the shape of mud huts or buildings of Afghan pattern. Some of the regiments are quartered in regular Afghan villages, out of which the inhabitants have been turned, but some of the buildings now occupied by troops are actually those which we built ourselves for our men when we occupied Kandahar in 1839, and which were found in fairly good condition when we returned here |Description of quarters.| forty years later, in 1879. Quarters of a not very luxurious description are provided for the officers, that is to say, they are given a room without doors or windows, and with a mud floor, and any improvements they wish to make they are required to do themselves. There is, of course, no furniture, and any luxuries one wants in that way we have to get for ourselves. The room I have got is at one end of a long low line of mud huts, the whole of which, except the 4 rooms at one end, which are allotted to me and my staff, and the four rooms at the other end which will be given to General Burrows and his staff, are occupied by artillery officers.

My set of quarters are in this shape, so I have one room to sleep, sit, and write in, and a room where we dine and breakfast, and which is, of course, public property. I have, as a special indulgence, a bath-room all to myself, but no one else has one. The room when I came into it was horrid; the floor was six inches deep in dust; there were no doors or windows, and altogether it was most unpromising. I have, however, had a floor made for it, the passage and dining-room, of a wonderful kind of stuff like Plaster of Paris which abounds here, and which hardens in the most wonderful way. I have had windows put in, and hope to have a door soon; and having bought a few pieces of a rough native carpeting in the city, and a couple of tables and chairs, my room begins to look very fair indeed. The mud walls are appropriately covered with yards of maps, which look very business-like, and in the small recesses I have had a few wooden shelves put up which quite do to hold my very scanty wardrobe. I find my room very hot and close at night, so I have pitched my little tent outside my door and sleep in it, watched over by a sentry whose sole duty is to guard his sleeping General, who can, therefore, slumber in the most perfect security. It would be rather monotonous to live with my Brigade Major and orderly officer only, as I am afraid we should get very tired of each other during the hot weather, so I am trying to get up a sort of mess between General Burrows and me, taking in our staff, and a couple of outsiders who have no special place to go to – viz., our Chaplain, Mr. Cane, and the Judge Advocate, Colonel Beville. The latter has agreed to manage the affair, so I have nothing to do with housekeeping, which is a blessing, and as Colonel Beville quite understands management and likes good things, I hope the affair will be a success, and that General Burrows will agree to join. The parson begged me to take him in, and I did not like to refuse, though I cannot say I care much about him (though perhaps he will improve on acquaintance), as he has the reputation of being rather inclined to quarrel and be difficult to manage. We will hope he is maligned and will prove not to have so unclerical a failing. A mess on service is a very rough affair, as we have no plate, crockery or linen, and live what is called camp fashion, that is, all the mess provides is tables and food, and each person's servant brings his plates, knives, forks, and spoons, and chairs, and when dinner or breakfast is over removes them. We shall, I daresay, in time get a few luxuries such as chairs, dishes, and perhaps a few table-cloths (I have 2 of my own for great occasions), and we have already made our dining-room look fairly comfortable (I am writing on 4th May), by putting down some carpets, and I have no doubt between Colonel Beville and me that we will get rid of as much unnecessary |Annoyances from flies and sand-flies.| roughness as we can. The great drawback of the whole place is the flies, which are most exasperating and pertinaceous. I am preparing a complete set of fortifications against them for my own room, by having net (which I have been fortunate to get in the city), such as musquito curtains are made of, nailed over the windows, and a door covered with net for the one entrance, so that I hope in time to be fairly free from them. They retire for the night, I am glad to say, about 7 o'clock, but as soon as they leave the sand-flies begin, and I think they are almost as bad, as they buzz and bite just like musquitos. They are a kind of very small gnat, and their bite is most irritating to some people, but they don't hurt me. The regiments are necessarily scattered over a large extent of ground, and the work is consequently very heavy on the men, as we have to post sentries very closely together to prevent the Afghans coming within our lines. The great proportion of the force is outside the city where I am living, but we hold the citadel, which is inside the city, where also we keep our arsenal and commissariat stores. A native infantry regiment and a detachment of a British infantry regiment hold the citadel, and the quarters occupied by both the officers and men there are much preferable to ours in the cantonments, as they are all regular native houses, many of which have gardens, and all some trees near and about them, and in this desert land a bit of green or a little shade have a value which no one who has not seen the country can understand. There is nothing striking about the actual city of Kandahar to anyone who has visited or seen an ordinary Indian town of the 5th or 6th rank. There are the usual bazaars with the occupants of the shops at work at their various trades in the front of their shops, and in many shops coarse English earthenware and cheap Birmingham and Manchester goods are exposed for sale, as is the case in even small villages in India. Raisins of all sorts and description, from the little sultanas up to dark purple ones, are sold in quantities, and seem to be a regular portion of the food of the poorest people. So far I have seen nothing curious or unusual which I would be tempted to buy, but then we cannot here wander about and go into the shops and ransack them for curiosities, as the people have a nasty trick of watching till a person is busy looking at things in a shop, and then coming up quietly and stabbing one in the back. It is consequently necessary, when we go shopping, to go in parties of 2 or 3, or take an escort, so as to always have some one on the watch against treachery, and as long as one takes this precaution they are too cowardly to attack in the open. The people in the streets are very picturesque, and most of them fine handsome men. No women are ever seen except very old ones, and even they generally wear the Turkish yashmak or veil which covers |Kandaharis – the Charsoo.| them from head to foot. In the centre of the city the 4 main streets meet under a curious large-domed building, around which are shops, and which is always crowded with a very mixed gathering of villains of all sorts. This place is called the Charsoo (or four waters), and it was in it that Lieutenant Willis, of the artillery, was murdered in broad day light by a Ghazi (N.B. – Next week I will explain who and what Ghazis are), who, however, was himself immediately killed. Any native attempting the life of any officer or soldier is now always hung in the Charsoo, which has had a very good effect.

Thursday, 22nd April, continued.– The newspapers have had a good deal of late about Ghazis, both here and at Cabul, and I dare say it will be well to explain who and what they are, as even here people have an idea that every Afghan who fights against us is a Ghazi, and there is some reason for this idea, as the primary meaning of the Persian word is "a warrior." The Ghazis, however, with whom we have had to deal, are fanatical Mahomedans who bind themselves by vows to kill one or more of the infidels (that is of us), and thereby earn a positive certainty of going straight to heaven. So convinced are they that if they can only kill an infidel their future happiness is secured, that they are perfectly indifferent as to whether they lose their own life in the attempt or not, in fact I believe they rather desire to be killed, and so enter at once on all the delights of a Mahomedan Paradise, the principal charm of which is, that they are there to have as many wives as ever they like, all, we will hope, warranted free from vice or temper, and requiring no management, but living as a happy family, without any jealousy or inclination to scratch out each others' eyes, as I fear would be the case in a similar establishment on earth. It will be easily understood that a gentleman with these ideas in his head is a very awkward customer, as, caring absolutely nothing as to what happens to himself, he has a very great pull over the man he attacks, who is extremely unwilling to be either wounded or killed. |Murderous assaults by Ghazis.| Moreover, although the Ghazis are undoubtedly brave to fool-hardiness, they don't at all disdain stratagem or treachery, and much prefer to stab their first victim quietly in the back, as the more men they kill before they are themselves killed, by so much the more is their position in Paradise improved. They, however (that is the real Ghazis), never use fire-arms, only swords or long Afghan knives, and always try for a personal hand-to-hand encounter. There have been many cases of attacks by Ghazis here, and though in every case the Ghazi was immediately himself killed, nothing seemed to stop the practice. There has, however, been no attempt of the kind for a month, but of course none of the necessary precautions are relaxed. The last case was that of a lad, who was a sworn Ghazi, attacking an officer with no other weapon than a shoemaker's awl, with which, however, he inflicted a couple of disagreeable wounds in the back before he was seen and seized. On Christmas day 5 men walked out of the city, and came into the barracks of the 59th, and (in open day) produced long knives from under their clothes, called out that they were Ghazis, and had come to kill anyone they could get at. Of course they were shot down, but so wild was the shooting that 4 of the men of the regiment were killed by the bullets from their comrades' rifles! The incident, however, shows what plucky fellows they are, as of course when they entered the barracks of the 59th, and openly declared their purpose, they must have known their lives were forfeited. In consequence of the number of Ghazis here, and the generally hostile feelings of the people to us, we are all required to go armed at all times, even when riding out or walking for exercise. It is a great worry, and I hate it, being a little sceptical as to the necessity for the extreme measure of precaution required, and am disposed to think a neat little bludgeon of a walking stick I possess would prove a much more serviceable defence to me than my regulation sword. Everyone carries loaded revolvers, especially when in the city, and I dare say the fact that we all do so being known, prevents many attempted attacks being made. The soldiers have to carry their rifles, and when they go into the town have to fix their bayonets, and altogether we live in a regular state of siege, which I would myself like to see ended by the application of some good strong remedies, and immediate and severe punishment for murderous attacks. Still, even then I fear we could not hope to change the nature of an Afghan, who is born a treacherous, lying, murdering scoundrel. Strong words, I know, but nothing more than they deserve, as even their admirers can say nothing in favor of their moral qualities.