полная версия

полная версияCornish Characters and Strange Events

The night was cold as well as tempestuous. On the blast of the wind came down torrents of rain. The men and women alike laboured hard to cast out of the boat the water that poured in. For sixteen hours darkness lasted. How may each have said with Gonzalo: "Now would I give a thousand furlongs of sea for an acre of barren ground, long heath, brown furze, anything. I would fain die a dry death." At length there rose a raw light in the south-east, against which the billows stood up black as ink. As the light grew, those in the boat found themselves encircled with sea, out of sight of land, and with the clouds scudding overhead, as if running a race. The storm continued all that day and the night following. Not only so, but also the third day and night the battle with the influx of water continued. There was no sleep for any; all had to fight the water for their lives. Happily they were not starving, for Mr. Sands had taken over to Falmouth in the boat a woman, the taverner's wife of the "Three Tuns," who had brought with her from Falmouth a shilling's worth of bread and three or four gallons of brandy. On this they subsisted.

On the fourth day in the morning, the gale abated, and at ten o'clock land was descried. Forthwith the rowers bent to their oars and steered towards it. When the whole party landed they discovered that they had been wafted over to the coast of Normandy; and they found themselves on French soil at the time that Queen Anne was engaged in war with Louis XIV. Marlborough had been in the Netherlands, and had reduced Venloo, Ruremonde, and the citadel of Liége. At sea Rooke had captured six vessels and sunk thirteen at Vigo, and Admiral Benbow had done wonders against a French fleet in the West Indies. The French were sore and irritated. So soon as Mr. Sands and his little party stepped on shore they were encountered by several men armed, who demanded who they were. They replied that they were English. One of the party stopping them understood our language, and inquired the occasion of these visitors landing on the enemy's shores, and by what expedient they had come over. They replied, and gave an account of their perilous voyage of three nights and four days.

Upon this a gentleman of the company asked Mr. Sands from what part of England he came, and when he replied that they were all from Cornwall, the same gentleman inquired further whether the leader of the party was named Sands; to this he replied, in some surprise, that he was.

"Then, monsieur," said the Frenchman, "I know you, and I can well remember your kindness and hospitality when I was wrecked off the Lizard some years ago. Then you received me into your house, and entertained me most generously."

This was an unexpected and welcome encounter. The gentleman then required the party to surrender what arms and money they had with them, and Mr. Sands handed over forty guineas that he had received at Falmouth for pilchards just before he was driven out to sea in the boat. He and his companions were required to yield themselves prisoners of war; and Mr. Sands was received into the gentleman's home. All next day were brought before a magistrate and examined, and orders were given that they should not be kept in custody as prisoners of war, but should be permitted to go about at liberty, and beg alms of the people. And the kind-hearted Normandy peasants and gentlemen showed them great favour, and supplied all their pressing wants.

The news of the event not only flew over the country, but reached the ears of the King, who thereupon ordered that the whole party should be sent back to England by the first transport ship for prisoners of war; which happened soon after.

Mr. Sands took leave of his kind host in whose house he had been hospitably entertained, and begged him to accept the forty guineas as some acknowledgment of his kindness. This, however, the gentleman refused to do, saying that he would take nothing at his hands, since God in such a wonderful manner had preserved him and his companions from the perils of the deep. Then Mr. Sands pressed five guineas on the wife of his host, begging her with that sum to purchase something which might remind her of him and his party; and this she reluctantly received.

So they parted, and all went on board a transport ship and were safely landed at Portsmouth; and in eight weeks after their departure from England returned to S. Keverne, to the great joy and surprise of their friends and relations, who had concluded that all of them had been drowned.

The Rev. Sampson Sandys was grandson of the gentleman who was carried over to France, as described. He lived at Lanarth to a great age. His daughter Eleanor married Admiral James Kempthorne, r. n. He was succeeded at Lanarth by his nephew, William Sandys, a colonel in the army of the East India Company, who rebuilt the house. It must be added that the original name of the family was not Sandys but Sands, and that it assumed the former name as more euphonious and as supposing a connection which, however, has not been proved to exist, with Lord Sandys of The Vine, and Ombersley, Worcestershire, and the Cumberland family of Graythwaite. At the same time, it assumed the arms of the same distinguished family, or, a fesse dancetté between three crosses crosslet fichée gules.

CHARLES INCLEDON

This, one of the sweetest tenor singers England has produced, was born at S. Keverne in Cornwall, in 1764, and was the son of a petty local surgeon and apothecary practising there.

At the age of seven he was introduced by Mr. Snow, one of the minor canons of Exeter Cathedral, to the organist, then named Langdon, and he afterwards became the pupil of William Jackson the composer, who was for many years organist of the cathedral. Jackson took great notice of the boy, and made him sing his own compositions at concerts in the city. On one occasion, when the assizes were on at Exeter, Judge Nares attended in state at the morning service in the cathedral, when Incledon sang the solo "Let my soul love," in the anthem, "Let my complaint come before Thee, O Lord," with such effect and beauty that the tears rolled down the judge's cheeks, and at the conclusion of Divine service he sent for the boy and presented him with five guineas.

Incledon was wont, on summer evenings, to seat himself on a rail in the cathedral close and sing, to the delight of an audience that always collected as soon as his bird-like voice was heard. On one such occasion he was singing the song "When I was a shepherd's maid," from The Padlock, when a gentleman in regimentals stepped forward and asked his name. Next day this officer, the Hon. Mr. Trevor, called on Jackson and asked permission to take the lad with him to Torquay, where he was going to visit Commodore Walsingham of the Thunderer, and he desired to give his friend and all on board ship the pleasure of hearing Incledon sing. Permission was accorded, and the boy was on board the vessel for three days, and sang several nautical and other songs, beginning with "Blow high, blow low." The Commodore was so delighted that he wrote to Incledon's parents and asked that the lad might be placed under him in the vessel; but the mother declined, and well was it that she did, for the Thunderer went down in a storm in the West Indies, and all hands on board were lost.

The kind reception accorded to Charles Incledon on board induced him to harbour the resolution to become a sailor, and accompanied by a fellow chorister, and carrying a bundle of linen, he ran away, hoping to reach Plymouth; but he was overtaken and brought back, and as a punishment was not allowed to wear his surplice in choir for a week.

But when his voice broke, then he was allowed to follow his bent, and he embarked on board the Formidable under Captain Stanton, and remained in her two years, till, disabled by a wound, he was left at Plymouth, and on his recovery was placed in a vessel commanded by Lord Harvey, afterwards Earl of Bristol. With this nobleman he sailed to Sta. Lucia, where the whole fleet was at anchor. Whilst there, Lord Harvey gave a dinner on board to his fellow commanders and other officers. At the same time the sailors before the mast enjoyed themselves with grog and songs. When Incledon sang, the lieutenant on deck ran to the cabin where the officers were regaling themselves, and told them that they had a nightingale on board, and would do well to hear it sing. Lord Harvey at once proceeded to the quarter-deck, heard Incledon sing the fine old traditional ballad, "'Twas Thursday in the Morn," and was so impressed that he bade him at once change his apparel and come to the state cabin. He did so and sang there "The Fight of the Monmouth and Foudroyant," "Rule Britannia," and some of Jackson's favourite canzonets. The officers applauded enthusiastically, and jocularly appointed him Singer to the British Fleet. He was released from the performance of manual duty, and sent for to assist at every entertainment that succeeded. He rose high in the favour of Admiral Pigot, the Commander-in-Chief, and made numerous friends and patrons.

In 1782 Incledon was in the engagement between the English fleet under Admiral Sir George Bridges, afterwards Lord Rodney, and the French fleet commanded by the Count de Grasse, when the former gained a complete victory.

At the expiration of the war Incledon was discharged at Chatham and proceeded to London, with strong recommendations from Lord Mulgrave and others to Mr. Colman of the Haymarket Theatre. Colman received him coldly, and gave him no hopes of an engagement. Then he went to Southampton, where he obtained an engagement at ten shillings and sixpence a week. But soon after, owing to some dispute, he left the company and went to Salisbury with a travelling company, and fell into great poverty and misery. However, he succeeded in obtaining an engagement at Bath with Mr. Palmer, the well-known theatrical manager, and the man who introduced mail-coaches into England. Here he received thirty shillings a week. He attracted the attention of Ranzzini, the arbiter of the musical entertainments at Bath; and this able man gave him valuable instruction in scientific singing. One evening, hearing Incledon sing Handel's "Total Eclipse," the Italian was so delighted that, catching hold of his hand, he left the piano, and leading him to the front of the platform exclaimed, "Ladies an jentleman, dis is my scholar!"

Thomas Harris, hearing him at Bath, proposed that he should sing and act at Covent Garden Theatre, and engaged him for three years at six, seven, and eight pounds a week. Hardly was this agreement made, when Linley, of Drury Lane, offered him twelve pounds a week, and to retain him for five years. But, although only a verbal agreement had been entered into with Harris, Incledon, to his honour, rejected the offer of Linley. It was unfortunate in more ways than one, as he would have profited by Linley's exquisite taste and instruction, as well as have earned nearly double what Harris offered. Moreover, he was very badly treated at Covent Garden, and often not given parts in which he could do himself justice. In 1809 came a rupture, and the managers dismissed him, and Incledon quitted London on a provincial tour. After two years he was re-engaged by Harris, at a salary of seventeen pounds a week, for a term of five years; but he stipulated that he should be given such rôles as suited him. This engagement was not fulfilled, and a fresh quarrel ensued that led to a final rupture at the end of three years, and he quitted Covent Garden for ever, refusing even to sing in the Oratorios performed there during Lent.

He had made his first appearance at Covent Garden in October, 1790, as Dermont in The Poor Soldier, by Shield. His vocal endowments were certainly great; he had a voice of uncommon power and sweetness, both in the natural and falsetto. The former was from A to G, a compass of about fourteen notes; the latter he could use from D to E or even F, or about ten notes. His natural voice was full and open, and of such ductility, that when he sang pianissimo it retained its original quality. His falsetto was rich, sweet, and brilliant, and totally unlike the other. He could use it with facility, and execute in it ornaments of a certain class with volubility and sweetness. His shake was good, and his intonation much more correct than is common to singers so imperfectly educated. But he never quite got over his West-country pronunciation. His strong point was the ballad, and that not the modern sentimental composition, but of the robust old school. When Ranzzini first heard him at Bath, rolling his voice upwards like a surge of the sea, till, touching the top note, it expired in sweetness, he exclaimed in rapture, "Corpo di Dio! it was ver' lucky dere vas some roof above or you would be heard by de angels in Heaven, and make dem jealous."

Incledon himself used to tell a story of the effect he produced upon Mrs. Siddons: "She paid me one of the finest compliments I ever received. I sang 'The Storm' after dinner; she cried and sobbed like a child. Taking both my hands, she said: 'All that I and my brother ever did is nothing to the effect you produce.'"

"I remember," says William Robson, in The Old Playgoer, "when the élite of taste and science and literature were assembled to pay the well-deserved compliment of a dinner to John Kemble, and to present him with a handsome piece of plate on his retirement, Incledon sang, when requested, his best song, 'The Storm.' The effect was sublime, the silence holy, the feeling intense; and while Talma was recovering from his astonishment, Kemble placed his hand on the arm of the great French actor, and said in an agitated, emphatic, and proud tone, 'That is an English singer.'" Marsden adds that Talma jumped up from his seat and embraced him.

Incledon sang with great feeling, and in "The Storm" he was able to throw his whole heart into the ballad, for not only had he encountered many a storm at sea, but he had been shipwrecked on a passage from Liverpool to Dublin, on the bar. Some of those on board were lost, but he saved himself and his wife by drawing her up to the round-top and lashing her and himself to it. From this perilous position, after a duration of several hours, they were rescued by some fishermen who saw the wreck from the shore.

Incledon belonged in town to "The Glee Club," composed of Shield, Bannister, Dignum, himself, and one or two others. It met on Sunday evenings during the season at the Garrick Coffee House, in Bow Street, once a fortnight. At one of these little gatherings Incledon was amusingly hoaxed. Though an admirable singer, he was a shockingly bad actor. When he came in one of the party informed him that an intended musical performance for a charitable purpose, in which he, Incledon, was to sing, had been abandoned, on account of the Bishop of London objecting to an actor performing in church. Incledon, who was an extremely irritable man, broke out in a violent strain, conceiving the word actor to have been employed as a term of reproach, and addressing himself to Bannister, said with great vehemence, "There, Charles, do you hear that?" "Why," said Bannister, "if I were you, I'd make his lordship prove his words."

Incledon one day was at Tattersall's, when Suett, the actor, also happened to be there, and asked him whether he had come to buy a horse. "Yes," said Charles, "I have. I must ride, it is good for my health. But why are you here, Dickey? Do you think that you know the difference between a horse and an ass?"

"Oh, yes," replied the comedian. "If you were among a thousand horses, I would know you immediately."

There was a public-house in Bow Street called "The Brown Bear," which was famous for a compound liquor, a mixture of beer, eggs, sugar, and brandy. Incledon and Jack Johnstone were partial to this, and frequently indulged themselves with it during the evening at the theatre, and, as a jest, occasionally obtained it in the following manner. When there happened to be several ladies of the theatre in the green-room, they took that opportunity to represent to them the hard case of the widow of a provincial actor, left with her children in great distress, and to solicit from them a few shillings to enable them to purchase some flannel during that inclement season. Having obtained contributions, they despatched the dresser to "The Brown Bear" for a quart of egg-hot, and had the modesty not to drink it all themselves, but to present a glass to each of the females who had subscribed, requesting them to drink to the health of the widow and the flannel. When Incledon and Johnstone had practised this trick several times, Quick, the comedian of the same theatre, bribed the dresser to infuse into the mixture a dose of ipecacuanha, and that brought the joke to an end. But the mixture thenceforth, without the last ingredient, was popularly called Flannel.

Incledon was a notoriously vain man. Vanity was his besetting sin. "In pronouncing his own name," says Mr. Matthews, "he believed he described all that was admirable in human nature. It would happen, however, that this perpetual veneration of self laid him open to many effects which, to any man less securely locked and bolted in his own conceit, would have opened the door to his understanding. But he had no room there for other than what it naturally contained; and the bump of content was all-sufficient to fill the otherwise aching void. Incledon called himself the 'English Ballad Singer' per se; a distinction he would not have exchanged for the highest in the realm of talent. Among many self-deceptions arising out of his one great foible, he was impressed with the belief that he was a reading man."

One day Matthews found him in his house deep in study. Incledon looked up at his visitor, and said, "My dear Matthews, I'm improving my mind. I'm reading a book that should be in the hands of every father and husband."

"What is it, Charles?" asked Matthews, and leaning over him saw that it was a volume of the Newgate Calendar!

It had become a habit, during a fagging run of a new opera at Covent Garden Theatre one season, for certain performers to club a batch or so of Madeira, of which they took a glass to their dressing-rooms. Incledon was continually finding fault with the quality, and praising up his own private stock of the same wine. At the close of the season, his brother actors had become weary of Incledon's grumbling over the Madeira, which they knew to be excellent. One night a fellow-actor, seeing a large key lying upon Incledon's dressing-table, labelled "Cellar," and Incledon happening at the time to be engaged on the stage till the end of the opera, despatched the dresser to Brompton Crescent with the key, with a request to Mrs. Incledon from her husband that she would send one dozen of his best Madeira by the bearer. Mrs. Incledon, wholly unsuspicious of any trick, did so. When Incledon left the stage, the confederates told him that they had got fresh and very first-rate Madeira now, as he had disliked what had been provided before. Incledon took a glass, made a wry face, took another, and said, "Beastly stuff! Never in my life tasted such cheap, vile stuff."

"Sorry, Incledon, you do not appreciate your own Madeira."

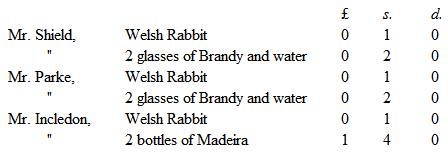

Incledon drank pretty heavily, but did not get drunk. Here is a bill for a slight evening collation at the Orange Coffee House, for him and two friends:

Parke, in his Musical Memoirs, relates an instance of Incledon's selfishness. He says of him that he was a singular compound of contrarieties, amongst which frugality and extravagance were conspicuous. "Mr. Shield the composer, Incledon, and I, lived for many years a good deal together. On one occasion Shield and myself dined with Incledon at his house in Brompton in the month of February. When I had arrived there, Incledon said to me, 'Bill, do you like ducks?' Conceiving, from the snow lying on the ground, that he meant wild ones, I replied, 'Yes, I like a good wild duck very well.' 'D – wild ducks!' said he: 'I mean tame ducks, my boy'; adding, 'I bought a couple in town for which I gave eighteen shillings.' Soon afterwards a letter arrived, announcing that Mr. Raymond, the stage-manager of Drury Lane Theatre, who was to have been of the party, could not come; in consequence of which, I presume, only one duck was placed on the dinner table, with some roast beef, etc. When Mrs. Incledon (who, as well as her husband, was fond of good living) had carved the duck, like a good wife she helped her husband to the breast part and to one of the wings, taking at the same time the other wing to herself, reserving for Shield and me the two legs and the back. Shield, who looked a little awkward at this specimen of selfishness and ill-manners, at first refused the limb offered to him, and I had declined taking the other: there appeared to be but a poor prospect of the legs walking off, till Shield relented and took one, and Incledon the other, so that they were speedily out of sight. The back, however, remained behind, and afforded a titbit for the servants."

On another occasion he was giving a dinner party, and a dish was brought to table heaped up, apparently, with fresh herrings. All the company, except Incledon and his wife, partook of these fish; some were helped a second time. When the herrings had been cleared away, there appeared beneath one fine white fish. "My dear," said Incledon, "what can that be?" "I believe it is a John Dory, Charles."

Some of the John Dory was offered to the company, but they had eaten enough fish, and so Incledon and his wife ate the John Dory between them.

Incledon, whilst very willing to hoax others, was easily taken in himself. As his dependence was entirely on his voice, he was very apprehensive of catching cold, which, in consequence, rendered him the occasional dupe of quackery.

During Mr. Kemble's management of Covent Garden Theatre, one of the wags among his fellow-actors informed him that a patent lozenge had just been invented and sold only at a jeweller's in Bond Street, which was an infallible cure for hoarseness. In order that he might the more readily take the bait, he was told that Kemble made frequent use of it. Incledon immediately inquired of the great actor, who very gravely answered, "Oh, yes, Charles; the patent lozenge is an admirable thing. I have derived the greatest benefit from it, when I kept it in my mouth all night."

Incledon accordingly went to Bond Street to purchase the valuable lozenge, and the man, who had been previously instructed, gave him a small pebble in a pill-box. Incledon arrived at the theatre next day with the stone in his mouth and spitting frequently. He was, of course, asked if the patent lozenge did him any good. "Yes," replied he, spitting; "I kept it in my mouth (spitting) all night, and (spitting again) it has this remarkable property, that it does not dissolve," and he spat again. The wag requested to see it, and the production of the pebble provoked a general laugh.

"Why, Charles," said Kemble, "this is a stone! I meant a patent lozenge. You should have gone to an apothecary's and not to a jeweller's for it."

Incledon, when he found that he was hoaxed, was full of wrath; his anger, however, soon subsided.

"Well," said he, "I can't grumble, for an apothecary who pretended to have supplied the jeweller with the lozenge, and who has received from me a letter belauding the nostrum, has undertaken in return to dispose of forty pounds' worth of tickets for my benefit."

On the occasion of this, or some other benefit, he could not refrain from going every morning to the box-office to see how many places were taken; and a week before the last, observing the names to be few besides those of his own private friends, he said to the box-keeper, Brandon, "D – it, Jem, if the nobility don't come forward, I shall cut but a poor figure this time."

"Don't be afraid," said Brandon; "I dare say we shall do a good deal for you to-day."

"I hope so," replied Incledon, "and as I go home to dinner I will look in again."

Incledon, who was not very familiar with Debrett's Peerage, returning at five o'clock in the afternoon, hastened to the book, and read aloud the following fictitious names, which Brandon, by way of a joke, had put down in his absence: "The Marquis of Piccadilly," "The Duke of Windsor."