полная версия

полная версияWhat Gunpowder Plot Was

“He confesseth that the powder was bought by the common purse of the confederates.

G. P. B., No. 49. In the Stowe copy the names of the Commissioners are omitted, and a list of fifteen plotters added. As the paper was inclosed in a letter to Edmondes of the 14th, these might easily be added at any date preceding that.

Father Gerard, who has printed this examination in his Appendix,63 styles it a draft, placing on the opposite pages the published confession of Guy Fawkes on November 17. That later confession, indeed, though embodying many passages of the earlier one, contains so many new statements, that it is a misapplication of words to speak of the one as the draft of the other. A probable explanation of the similarity is that when Fawkes was re-examined on the 17th, his former confession was produced, and he was required to supplement it with fresh information.

In one sense, indeed, the paper from which the examination of the 8th has been printed both by Father Gerard and myself, may be styled a draft, not of the examination of the 17th, but of a copy forwarded to Edmondes on the 14th.64 The two passages crossed out and printed above65 in italics have been omitted in the copy intended for the ambassadors. All other differences, except those of punctuation, have been given in my notes, and it will be seen that they are merely the changes of a copyist from whom absolute verbal accuracy was not required. Father Gerard, indeed, says that in the original of the so-called draft five paragraphs were ‘ticked off for omission.’ He may be right, but in Winter’s declaration of November 23, every paragraph is marked in the same way, and, at all events, not one of the five paragraphs is omitted in the copy sent to Edmondes.

In any other sense to call this paper a draft is to beg the whole question. What we want to know is whether it was a copy of the rough notes of the examination, signed by Fawkes himself, or a pure invention either of Salisbury or of the seven Commissioners and the Attorney-General. Curiously enough, one of the crossed out passages supplies evidence that the document is a genuine one. The first, indeed, proves nothing either way, and was, perhaps, left out merely because it was thought unwise to allow it to be known that the King had been so carelessly guarded that Percy had been admitted to his presence with a sword by his side. The second contains an intimation that the conspirators did not intend to rely only on a Catholic rising. They expected to have on their side Protestants who disliked the union with Scotland, and who were ready to protest ‘against all strangers,’ that is to say, against all Scots. We can readily understand that Privy Councillors, knowing as they did the line taken by the King in the matter of the union, would be unwilling to spread information of there being in England a Protestant party opposed to the union, not only of sufficient importance to be worth gaining, but so exasperated that even these gunpowder plotters could think it possible to win them to their side. Nor is this all. If it is difficult to conceive that the Commissioners could have allowed such a paragraph to go abroad, it is at least equally difficult to think of their inventing it. We may be sure that if Fawkes had not made the statement, no one of the examiners would ever have committed it to paper at all, and if the document is genuine in this respect, why is it not to be held genuine from beginning to end?

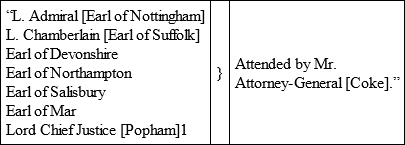

Father Gerard, indeed, objects to this view of the case that the document ‘is unsigned; the list of witnesses is in the same handwriting as the rest, and in no instance is a witness indicated by such a title as he would employ for his signature. Throughout this paper Fawkes is made to speak in the third person, and the names of accomplices to whom he refers are not given.’66 All this is quite true, and unless I am much mistaken, are evidences for the genuineness of the document, not for its fabrication. If Salisbury had wished to palm off an invention of his own as a copy of a true confession by Fawkes, he surely would not have stuck at so small a thing as an alleged copy of the prisoner’s signature, nor is it to be supposed that the original signatures of the Commissioners would appear in what, in my contention, is a copy of a lost original. As for the titles Lord Admiral and Lord Chamberlain being used instead of their signatures, it was in accordance with official usage. A letter, written on January 21, 1604-5, by the Council to the Judges, bears nineteen names at the foot in the place where signatures are ordinarily found. The first six names are given thus: – ‘L. Chancellor, L. Treasurer, L. Admirall, L. Chamberlaine, E. of Northumberland, E. of Worcester.’67 Fawkes is made to speak in the third person in all the four preceding examinations, three of which bear his autograph signature. That the names of accomplices are not given is exactly what one might expect from a man of his courage. All through the five examinations he refused to break his oath not to reveal a name, except in the case of Percy in which concealment was impossible. It required the horrible torture of the 9th to wring a single name from him.

Moreover, Father Gerard further urges what he intends to be damaging to the view taken by me, that a set of questions formed by Coke upon the examination of the 7th, apparently for use on the 8th, is ‘not founded on information already obtained, but is, in fact, what is known as a “fishing document,” intended to elicit evidence of some kind.’68 Exactly so! If Coke had to fish, casting his net as widely as Father Gerard correctly shows him to have done, it is plain that the Government had no direct knowledge to guide its inquiries. Father Gerard’s charge therefore resolves itself into this: that Salisbury not only deceived the public at large, but his brother-commissioners as well. Has he seriously thought out all that is involved in this theory? Salisbury, according to hypothesis, gets an altered copy of a confession drawn up, or else a confession purely invented by himself. The clerk who makes it is, of course, aware of what is being done, and also the second clerk,69 who wrote out the further copy sent to Edmondes. Edmondes, at least, received the second copy, and there can be little doubt that other ambassadors received it also. How could Salisbury count on the life-long silence of all these? Salisbury, as the event proved, was not exactly loved by his colleagues, and if his brother-commissioners – every one of them men of no slight influence at Court – had discovered that their names had been taken in vain, it would not have been left to the rumour of the streets to spread the news that Salisbury had been the inventor of the plot. Nay, more than this. Father Gerard distinctly sets down the story of the mine as an impossible one, and therefore one which must have been fabricated by Salisbury for his own purposes. The allegation that there had been a mine was not subsequently kept in the dark. It was proclaimed on the house-tops in every account of the plot published to the world. And all the while, it seems, six out of these seven Commissioners, to say nothing of the Attorney-General, knew that it was all a lie – that Fawkes, when they examined him on the 8th, had really said nothing about it, and yet, neither in public, nor, so far as we know, in private – either in Salisbury’s lifetime or after his death – did they breathe a word of the wrong that had been done to them as well as to the conspirators!

CHAPTER III.

THE LATER DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE

Having thus, I hope, established that the story of the mine and cellar is borne out by Fawkes’s own account, I proceed to examine into the objections raised by Father Gerard to the documentary evidence after November 8, the date of Fawkes’s last examination before he was subjected to torture. In the declaration, signed with his tortured hand on the 9th, before Coke, Waad and Forsett,70 and acknowledged before the Commissioners on the 10th, Fawkes distinctly refers to the examination of the 8th. “The plot,” he says, “was to blow up the King with all the nobility about him in Parliament, as heretofore he hath declared, to which end, they proceeded as is set down in the examination taken (before the Lords of the Council Commissioners) yesternight.” Here, then, is distinct evidence that Fawkes acknowledged that the examination of the 8th had been taken in presence of the Commissioners, and thus negatives the theory that that examination was invented or altered by Salisbury, as these words came on the 10th under the eyes of the Commissioners themselves.71

The fact is, that the declaration of the 9th fits the examination of the 8th as a glove does a hand. On the 8th, before torture, Fawkes described what had been done, and gave the number of persons concerned in doing it. On the 9th he is required not to repeat what he had said before, but to give the missing names. This he now does. It was Thomas Winter who had fetched him from the Low Countries, having first communicated their design to a certain Owen.72 The other three, who made up the original five, were Percy, Catesby, and John Wright. It was Gerard who had given them the Sacrament.73 The other conspirators were Sir Everard Digby, Robert Keyes, Christopher Wright, Thomas74 Grant, Francis Tresham, Robert Winter, and Ambrose Rokewood. The very order in which the names come perhaps shows that the Government had as yet a very hazy idea of the details of the conspiracy. The names of those who actually worked in the mine are scattered at hap-hazard amongst those of the men who merely countenanced the plot from a distance.

However this may be, the 9th, the day on which Fawkes was put to the torture, brought news to the Government that the fear of insurrection need no longer be entertained. It had been known before this that Fawkes’s confederates had met on the 5th at Dunchurch on the pretext of a hunting match,75 and had been breaking open houses in Warwickshire and Worcestershire in order to collect arms. Yet so indefinite was the knowledge of the Council that, on the 8th, they offered a reward for the apprehension of Percy alone, without including any of the other conspirators.76 On the evening of the 9th77 they received a letter from Sir Richard Walsh, the Sheriff of Worcestershire: —

“We think fit,” he wrote, “with all speed to certify your Lordships of the happy success it hath pleased God to give us against the rebellious assembly in these parts. After such time as they had taken the horses from Warwick upon Tuesday night last,78 they came to Mr. Robert Winter’s house to Huddington upon Wednesday night,79 where – having entered – [they] armed themselves at all points in open rebellion. They passed from thence upon Thursday morning80 unto Hewell – the Lord Windsor’s house – which they entered and took from thence by force great store of armour, artillery of the said Lord Windsor’s, and passed that night into the county of Staffordshire unto the house of one Stephen Littleton, Gentleman, called Holbeche, about two miles distant from Stourbridge whither we pursued, with the assistance of Sir John Foliot, Knight, Francis Ketelsby, Esquire, Humphrey Salway, Gentleman, Edmund Walsh, and Francis Conyers, Gentlemen, with few other gentlemen and the power and face of the country. We made against them upon Thursday morning,[81] and freshly pursued them until the next day,81 at which time about twelve or one of the clock in the afternoon, we overtook them at the said Holbeche House – the greatest part of their retinue and some of the better sort being dispersed and fled before our coming, whereupon and after summons and warning first given and proclamation in his Highness’s name to yield and submit themselves – who refusing the same, we fired some part of the house and assaulted some part of the rebellious persons left in the said house, in which assault, one Mr. Robert Catesby is slain, and three others verily thought wounded to death whose names – as far as we can learn – are Thomas Percy, Gentleman, John Wright, and Christopher Wright Gentlemen, and these are apprehended and taken Thomas Winter Gentleman, John Grant Gentleman, Henry Morgan Gentleman, Ambrose Rokewood Gentleman, Thomas Ockley carpenter, Edmund Townsend servant to the said John Grant, Nicholas Pelborrow, servant unto the said Ambrose Rokewood, Edward Ockley carpenter, Richard Townsend servant to the said Robert Winter, Richard Day servant to the said Stephen Littleton, which said prisoners are in safe custody here, and so shall remain until your Honours good pleasures be further known. The rest of that rebellious assembly is dispersed, we have caused to be followed with fresh suite and hope of their speedy apprehension. We have also thought fit to send unto your Honours – according unto our duties – such letters as we have found about the parties apprehended; and so resting in all duty at your Honours’ further command, we take leave, from Stourbridge this Saturday morning, being the ixth of this instant November 1605.

“Your Honours’ most humble to be commanded,

“Rich. Walsh.”

Percy and the two Wrights died of their wounds, so that, in addition to Fawkes, Thomas Winter was the only one of the five original workers in the mine in the hands of the Government. Of the seven others who had been named in Fawkes’s confession of the 9th, Christopher Wright had been killed; Rokewood, Robert Winter, and Grant had been apprehended at Holbeche; Sir Everard Digby, Keyes, and Tresham were subsequently arrested, as was Bates a servant of Catesby.

That for some days the Government made no effort to get further information about the mine and the cellar cannot be absolutely proved, but nothing bearing on the subject has reached us except that, on the 14th, when a copy of Fawkes’s deposition of the 8th was forwarded to Edmondes, the names of the twelve chief conspirators are given, not as Fawkes gave them on the 9th, in two batches, but in three, Robert Winter and Christopher Wright being said to have joined after the first five, whilst Rokewood, Digby, Grant, Tresham, and Keyes are said to have been ‘privy to the practice of the powder but wrought not at the mine.’82 As Keyes is the only one whose Christian name is not given, this list must have been copied from one now in the Record Office, in which this peculiarity is also found, and was probably drawn up on or about the 10th83 from further information derived from Fawkes when he certified the confession dragged from him on the preceding day.[84]

What really seems to have been at this time on the minds of the investigators was the relationship of the Catholic noblemen to the plot. On the 11th Talbot of Grafton was sent for. On the 15th Lords Montague and Mordaunt were imprisoned in the Tower. On the 16th Mrs. Vaux and the wives of ten of the conspirators were committed to various aldermen and merchants of London.84 When Fawkes was re-examined on the 16th,85 by far the larger part of the answers elicited refer to the hints given, or supposed to have been given, to Catholic noblemen to absent themselves from Parliament on the 5th. Then comes a statement about Percy buying a watch for Fawkes on the night of the 4th and sending it ‘to him by Keyes at ten of the clock at night, because he should know how the time went away.’ The last paragraph alone bears upon the project itself. “He also saith he did not intend to set fire to the train [until] the King was come to the House, and then he purposed to do it with a piece of touchwood and with a match also, which were about him when he was apprehended on the 4th day of November at 11 of the clock at night that the powder might more surely take fire a quarter of an hour after.”

The words printed in italics are an interlineation in Coke’s hand. They evidently add nothing of the slightest importance to the evidence, and cannot have been inserted with any design to prejudice the prisoner or to carry conviction in quarters in which disbelief might be supposed to exist. Is not the simple explanation sufficient, that when the evidence was read over to the examinee, he added, either of his own motion or on further question, this additional information. If this explanation is accepted here, may it not also be accepted for other interlineations, such as that relating to the cellar in the first examination?86

That the examiners at this stage of the proceedings should not be eager to ask further questions about the cellar and the mine was the most natural thing in the world. They knew already quite enough from Fawkes’s earlier examinations to put them in possession of the general features of the plot, and to them it was of far greater interest to trace out its ramifications, and to discover whether a guilty knowledge of it could be brought home either to noblemen or to priests, than to attain to a descriptive knowledge of its details, which would be dear to the heart of the newspaper correspondent of the present day. Yet, after all, even in 1605, the public had to be taken into account. There must be an open trial, and the more detailed the information that could be got the more verisimilitude would be given to the story told. It is probably, in part at least, to these considerations, as well as to some natural curiosity on the part of the Commissioners themselves, that we owe the examinations of Fawkes on the 17th and of Winter on the 23rd.

“Amongst all the confessions and ‘voluntary declarations’ extracted from the conspirators,” writes Father Gerard, “there are two of exceptional importance, as having furnished the basis of the story told by the Government, and ever since generally accepted. These are a long declaration made by Thomas Winter, and another by Guy Fawkes, which alone were made public, being printed in the ‘King’s Book,’ and from which are gathered the essential particulars of the story, as we are accustomed to hear it.”

If Father Gerard merely means that the story published by the Government rested on these two confessions, and that the Government publications were the source of all knowledge about the plot till the Record Office was thrown open, in comparatively recent years, he says what is perfectly true, and, it may be added, quite irrelevant. If he means that our knowledge at the present day rests on these two documents, he is, as I hope I have already shown, mistaken. With the first five examinations of Fawkes in our hands, all the essential points of the conspiracy, except the names, are revealed to us. The names are given in the examination under torture, and a day or two later the Government was able to classify these names, though we are unable to specify the source from which it drew its information. If both the declarations to which Father Gerard refers had been absolutely destroyed we should have missed some picturesque details, which assist us somewhat in understanding what took place; but we should have been able to set forth the main features of the plot precisely as we do now.

Nevertheless, as we do gain some additional information from these documents, let us examine whether there are such symptoms of foul play as Father Gerard thinks he can descry. Taking first Fawkes’s declaration of November 17, it will be well to follow Father Gerard’s argument. He brings into collocation three documents: first the interrogatories prepared by Coke after the examination of the 7th, then the examination of the 8th, which he calls a draft, and then the full declaration of the 17th, which undoubtedly bears the signature of Fawkes himself.

That the three documents are very closely connected is undeniable. Take, for instance, a paragraph to which Father Gerard not unnaturally draws attention, in which the repetition of the words ‘the same day’ proves at least partial identity of origin between Coke’s interrogatories and the examination founded on them on the 8th.87

“Was it not agreed,” asks Coke, “the same day that the act should have been done, the same day, or soon after, the person of the Lady Elizabeth should have been surprised?” “He confesseth,” Fawkes is stated to have said, “that the same day this detestable act should have been performed the same day should other of their confederacy have surprised the Lady Elizabeth.” Yet before setting down Fawkes’s replies as a fabrication of the Government, let us remember how evidence of this kind is taken and reported. If we take up the report of a criminal trial in a modern newspaper we shall find, for the most part, a flowing narrative put into the mouths of witnesses. John Jones, let us say, is represented as giving some such evidence as this: “I woke at two o’clock in the morning, and, looking out of window, saw by the light of the moon John Smith opening the stable door,” &c. Nobody who has attended a law court imagines John Jones to have used these consecutive words. Questions are put to him by the examining counsel. When did you wake? Did you see anyone at the stable door? How came you to be able to see him, and so forth; and it is by combining these questions with the Yes and No, and other brief replies made by the witness, that the reporter constructs his narrative with no appreciable violation of truth. Is it not reasonable to suppose that the same practice prevailed in 1605? Fawkes, I suppose, answered to Coke’s question, “Yes, others of the confederates proposed to surprise her,” or something of the sort, and the result was the combination of question and answer which is given above.

What, however, was the relation between the examination of the 8th and the declaration of the 17th? Father Gerard has printed them side by side,88 and it is impossible to deny that the latter is founded on the former. Some paragraphs of the examination are not represented in the declaration, but these are paragraphs of no practical importance, and those that are represented are modified. The modifications admitted, however, are all consistent with what is a very probable supposition, that the Government wanted to get Fawkes’s previous statements collected in one paper. He had given his account of the plot on one occasion, the names of the plotters on another, and had stated on a third that they were to be classified in three divisions – those who worked first at the mine, those who worked at it afterwards, and those who did not work at all. If the Government drew up a form combining the three statements and omitting immaterial matter, and got Fawkes to sign it, this would fully account for the form in which we find the declaration. At the present day, we should object to receive evidence from a man who had been tortured once and might be tortured again; but as this declaration adds nothing of any importance to our previous knowledge, it is unnecessary to recur to first principles on this occasion.89

Winter’s examination of the 23rd, as treated by Father Gerard, raises a more difficult question. The document itself is at Hatfield, and there is a copy of it in the ‘Gunpowder Plot Book’ in the Public Record Office. “The ‘original’ document,” writes Father Gerard,90 “is at Hatfield, and agrees in general so exactly with the copy as to demonstrate the identity of their origin. But while, as we have seen, the ‘copy’ is dated November 23rd, the ‘original’ is dated on the 25th.” In a note, we are told ‘that this is not a slip of the pen is evidenced by the fact that Winter first wrote 23, and then corrected it to 25.’ To return to Father Gerard’s text, we find, “On a circumstance so irregular, light is possibly thrown by a letter from Waad, the Lieutenant of the Tower, to Cecil91 on the 20th of the same month. ‘Thomas Winter,’ he wrote, ‘doth find his hand so strong, as after dinner he will settle himself to write that he hath verbally declared to your Lordship, adding what he shall remember.’ The inference is certainly suggested that torture had been used until the prisoner’s spirit was sufficiently broken to be ready to tell the story required of him, and that the details were furnished by those who demanded it. It must, moreover, be remarked that, although Winter’s ‘original’ declaration is witnessed only by Sir E. Coke, the Attorney-General, it appears in print attested by all those whom Cecil had selected for the purpose two days before the declaration was made.”

Apparently Father Gerard intends us to gather from his statement that the whole confession of Winter was drawn up by the Government on or before the 23rd, and that he was driven on the 25th by fears of renewed torture to put his hand to a tissue of falsehoods contained in a paper which the Government required him to copy out and sign. The whole of this edifice, it will be seen, rests on the assertion that Winter first wrote 23 and then corrected it to 25.