полная версия

полная версияThe Cradle of the Christ: A Study in Primitive Christianity

All these transformations, it will be observed, came in the order of mental development, each timely and beneficent in its place. The crowning and the dis-crowning were alike inevitable and good. The glorification and the disappearance were both justified. The final change comes neither too late nor too soon; not too late, for still the immense majority of mankind live in sentiment and imagination, worship ideal shapes, being quite incapable of appreciating knowledge, loving truth, or obeying principles. It will be generations yet, before any save the comparatively few think they can live without this great friend at their side. Sentiment is conservative. The poetic feeling detains in picturesque form the ideas which if exposed to the action of clear intelligence would be rejected as unsubstantial. The imagination like the ivy loves to beautify ruins, making even robber castles and deserted palaces attractive to tourists. Wordsworth, the poet of Nature expresses the feeling that will at times come over powerful and cultivated minds, in moods of sentiment —

The world is too much with us; late and soon,Getting and spending we lay waste our powers.Little we see in Nature that is ours;We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!This Sea that bares her bosom to the Moon,The winds that will be howling at all hours,And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers,For this, for everything, we are out of tune,It moves us not; – Great God! I'd rather beA Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn,Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea,Or hear old Triton blow his wreathed horn.This is pure sentiment. The sea was as lovely to Wordsworth, is as lovely to Tyndall, as it was to the superstitious Greeks. The winds awaken similar emotions in the sensitive being. Why then, should Wordsworth, having all that is or ever was to be had, beauty of form, movement, color, regret the superstition that peopled the sea with fanciful beings and animated the winds with supernatural spirits? Why not be content with the facts, and the more content, because the fancies are gone that disguised them? Is it not a weakness to love dreams better than realities? Mr. Leslie Stephen, in his admirable "History of English Thought in the XVIII century" explains this mood of mind by saying that for the expression of feeling symbols are necessary, and superstition supplies all the symbols there are. The bare truth may awaken emotions, but it gives them no voice, and emotion unuttered, becomes feeble; in all but sensitive natures it dies. "In time," says Mr. Stephen, "the loss may be replaced, the new language may be learnt; we may be content with direct vision, instead of mixing facts with dreams; but the process is slow; and till it is completed, the new belief will not have the old power over the mind. The symbols which have been associated with the hopes and fears, with the loftiest aspirations and warmest affections of so many generations may be proved to be only symbols; but they long retain their power over the imagination." It is not wise, therefore, to be impatient with sentiment that has so valid an excuse; nor is it magnanimous to stigmatize as weak and childish the romantic attachment to the symbol which is all that remains, which, with the unthinking, unadventurous multitude is so large a part of what abides of the mind's spiritual endowment. We must be patient with the conservatism that is born, not of fear, but of feeling, sympathizing when we can, with those that grieve when the idols lose their sanctity, and rejoicing that sentiment has the power to break the shock caused by the sudden dispelling of illusions. At the same time, it must be remembered that intellect is the propelling force in the intellectual world; that the acute, unimaginative, determined minds, impatient of the mists, however beautiful, that conceal knowledge, clear a way for the homes and gardens of the new generations; that the love of truth, simple and unadorned, is the mother at last of real beauty.

The disappearance of the resplendent figure of the Christ from the heaven of our philosophy has not, therefore, come too soon; for thinking, clear-sighted, brave and resolute minds there are. Discerning eyes, bright and gentle, look out and see the fields, sown with new seed, whitening for a new harvest. To such as these Jesus is no longer necessary for faith in humanity, for enthusiasm and constancy in humanity's service. Heroic men and saintly women exist in such numbers and in such variety that they sit in judgment on the judges, and call the censors to account. The education of mankind in the qualities that knit and adorn society has gone so far that these virtues require no longer a super-human representative to give them honor. Knowledge of every kind has so abundantly increased that the aid of revelation to throw light on important subjects is not demanded. Philosophy, literature, science have taken possession of the fields once occupied by the surmise of faith, and are carefully mapping out the departments of speculation. The problems that remain dark, – and they are the many, – we are content should remain so till light comes from the proper sources. The darkest of them, no darker than they have always been, are no longer complicated by the difficulties of revelation which added enigmas where there were enough before, but lie open to all the light that can be thrown upon them. The confusion introduced into the orderly sequence of the world's development by the exceptionally providential man subsides, and the cumulative power of history is brought to bear on the necessities of the hour. Relieved from the sacred duty of turning backward for the form of the perfect man, thereby overlooking the present and suspecting the future, we are permitted to estimate fairly the conditions of the present existence, and to prepare for the future with unprejudiced, rational minds. The standard of moral attainment and the quality of moral character set up as authoritative by any single race, however distinguished, by any one era, however brilliant, abuses and injures the standards of other races, and casts suspicion on the attributes of other generations. The belief that at some time humanity has already come to full flower, discourages the laborers in the human garden. Humanity is still a-making; its perfection is prophecy not history.

The lesson of the hour is self-dependence, or rather, if we prefer, dependence on the laws of reason. It will be a gain for truth when true thoughts shall be welcomed because they are true, not because they are spoken by a particular sage; when erroneous thoughts shall be judged by their demerits, without fear of casting affront on the character of a saint. James Martineau's tender wisdom gains nothing in charm by being attributed to his beautiful fiction of a Christ, and Mr. Moody's painful caricatures of Providence have an unfair advantage in being sheltered behind the authority of the Hebrew Messiah. The holy beauty of Mr. Martineau's ideal person is more than offset by the awful grandeur of the "evangelical" Avenger, equally a creature of imagination. In the realm of fancy the lurid conception outlasts and overwhelms the radiant one. Safety lies in withdrawal from the realm of fancy, and domestication in the humbler realm of fact. The lesson can be now safely taught. Let men learn it as soon as they will. Dependence on individual personalities has been the rule hitherto; dependence on general ideas and organic laws, dependence on discovered fact and intelligent conclusion, will be the reliance hereafter. As for the demands of the heart, which must have persons to cling to, they will adjust themselves to the new science and will satisfy themselves in the future as they have done in the past. Are all the fine personalities dead? Then the sooner we give them a chance to revive by removing the prodigious personality whose shadow has blighted them, the better for us. Are there none to love with enthusiastic ardor? Who have made us think so, if not they by whom all amiable and adorable attributes have been claimed before? Are there no feet it is an honor to sit at, no heads it is a privilege to anoint, no hands it is a dignity to kiss? Whose fault can this be, if not theirs who challenged the adoration of men and women and pronounced it consecrated because rendered to him for one? Are there no leaders worth following, no causes worth espousing? They that think so must be listening to the voice that bade men follow in Galilee, and sighing because they cannot take up the cross that was imposed on the faithful in the cities of Judæa.

The imagination of man has not lost its power or forgotten its function since it performed the prodigious task of enthroning its hope by the side of the godhead. It is adequate to new and healthier performance. A world of fresh materials lies before it; new heavens display their glories; a new earth offers opportunity and prospect; a new humanity presents its varieties of good and evil. New beauties gladden the open vision; new glories fascinate the kindling hope. The regions of possibility, so far from being exhausted, have but begun to disclose their treasures. The realities of to-day surpass the ideals of yesterday. Art has a new birth. Poetry has a new birth. Philosophy teems with new births. These all look forward with confident expectation. Why should religion, which has built up more grandeurs than any of them, turn her back to the new day, confess her creative power exhausted, and creep back to the images of her own idolatry? The Christ-idea, become human, will surpass its old triumphs.

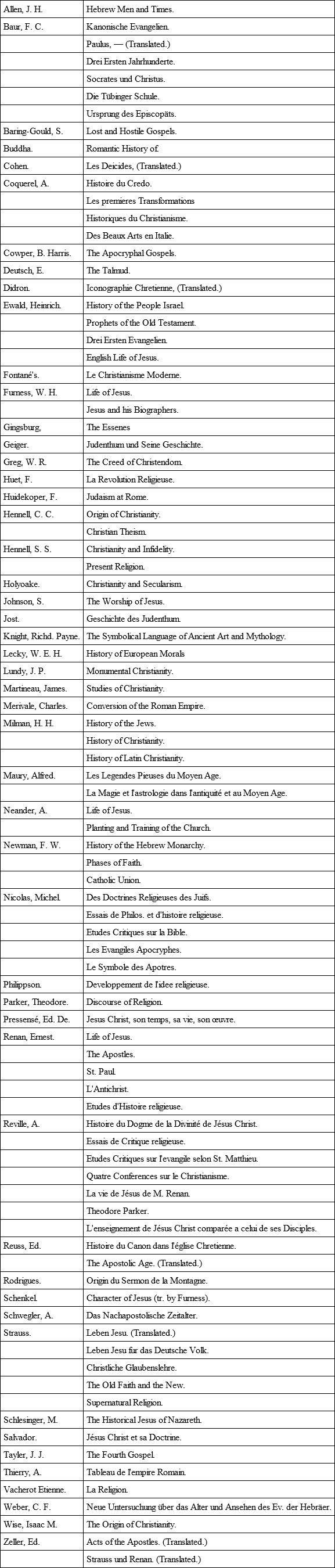

AUTHORITIES

To meet the wishes of such as may desire to know on what grounds his opinions are founded, or to pursue them further, the author gives the titles of a few books that may be profitably consulted. It were easy to make a long list of erudite works; much easier than to make a short list of accessible and suggestive volumes. In an essay prepared for the intelligent and thoughtful, not for the learned or scholarly class, reference to stores of erudition would be out of place. For this reason, the pages are left unencumbered with notes, and the books cited are purposely such as come within easy reach of general readers. The better known book is preferred before the less known, the conservative when it will answer the purpose, before the destructive. If the whole case were presentable in English, none but English authorities would be mentioned. Unfortunately for the general reader, the best literature is in German or French, much of which is still untranslated. To indicate these is a necessity for those who are acquainted with those languages, while those who are not, will, it is believed, find enough in English writings reasonably to satisfy their need.

The titles of the books indicate sufficiently the points on which they throw light. The classical references, which are numerous, are most copious in Denis and Huidekoper, though Lecky, Renan, Johnson and others cite all the most important.

1

Origin of Christianity, p. 335-341.

2

Bellum Judaicum, VII. 17.

3

See Milman's Jews, II. p. 461.

4

See Huidekoper's "Judaism in Rome," p. 325-329.

5

See "Judaism in Rome," p. 245.

6

History of Christianity, II; p. 8.

7

Vol. I.; p. 528.

8

For references, see Lecky's "European Morals," II., p. 79-81.

9

See Denis, II., p. 55-218.

10

The character and influence of the "Gospel of the Hebrews" and of other books of the same kind is considered in full by Mr. S. Baring-Gould in "The Lost and Hostile Gospels." Mr. Baring-Gould argues that while neither of our present Gospels is entitled to be called genuine in the ordinary sense, they contain authentic biographical materials. It is his opinion that "at the close of the first century almost every Church had its own Gospel, with which alone it was acquainted. But it does not follow that these Gospels were not as trustworthy as the four which we now alone recognize." (p. 23.) Mr. Baring-Gould's argument is not strong. The first mention of the "Gospel of the Hebrews" is no earlier than the middle of the second century; the remaining fragments of it are too few and too undecisive to be of weight; and it was, by all confession, written in the interest of the Nazarene or Judaizing Christians. Mr. Baring-Gould himself classes it with the Clementine writings and calls them "The Lost Petrine Gospels."