полная версия

полная версияПолная версия

The Toy Shop (1735) The King and the Miller of Mansfield (1737)

Gent. [Aside.] A proper Object to display your Folly.

Mast. Pray, Madam, moderate your Grief; you ought to thank Heaven 'tis not your Husband.

3 La. Oh, what is Husband, Father, Mother, Son, to my dear, precious Chloe! – No, no, I cannot live without the Sight of his dear Image; and if you cannot make me the exact Effigies of this poor dead Creature, and cover it with his own dear Skin, so nicely that it cannot be discern'd, I must never hope to see one happy Day in Life.

Mast. Well, Madam, be comforted, I will do it to your Satisfaction.

[Taking the Box.3 Lady. Let me have one look more. Poor Creature! O cruel Fate, that Dogs are born to die.

[Exit weeping.Gent. What a Scene is here! Are not the real and unavoidable Evils of Life sufficient, that People thus create themselves imaginary Woes?

Mast. These, Sir, are the Griefs of those that have no other. Did they once truly feel the real Miseries of Life, ten thousand Dogs might die without a Tear.

Enter a second Gentleman2 Gent. I want an Ivory Pocket-book.

Mast. Do you please to have it with Directions, or without?

2 Gent. Directions! what, how to use it?

Mast. Yes, Sir.

2 Gent. I should think, every Man's own Business his best Direction.

Mast. It may so. Yet there are some general Rules, which it equally behoves every Man to be acquainted with. As for Instance: Always to make a Memorandum of the Benefits you receive from others. Always to set down the Faults or Failings, which from Time to Time you discover in yourself. And, if you remark any Thing that is ridiculous or faulty in others, let it not be with an ill-natur'd Design to hurt or expose them, at any Time, but with a Nota bene, that it is only for a Caution to your self, not to be guilty of the like. With a great many other Rules of such a Nature as makes one of my Pocket-books both a useful Monitor and a very entertaining Companion.

2 Gent. And pray, what's the Price of one of them?

Mast. The Price is a Guinea, Sir.

2 Gent. That's very dear. But, as it's a Curiosity – [Pays for it, and Exit.]

Enter a BeauBeau. Pray, Sir, let me see some of your handsomest Snuff-boxes.

Mast. Here's a plain Gold one, Sir, a very neat Box; here's a Gold enamell'd; here's a Silver one neatly carv'd and gilt; here's a curious Shell, Sir, set in Gold.

Beau. Dam your Shells; there's not one of them fit for a Gentleman to put his Fingers into. I want one with some pretty Device on the Inside of the Lid; something that may serve to joke upon, or help one to an Occasion to be witty, that is, smutty, now and then.

Mast. And are witty and smutty then synonimous Terms?

Beau. O dear Sir, yes; a little decent Smutt is the very Life of all Conversation. 'Tis the Wit of Drawing-Rooms, Assemblies, and Tea-tables. 'Tis the smart Raillery of fine Gentlemen, and the innocent Freedom of fine Ladies. 'Tis a Double Entendre, at which the Coquet laughs, the Prude looks grave, the Modest blush, but all are pleas'd with.

Mast. That it is the Wit and the Entertainment of all Conversations, I believe, Sir, may, possibly, be a Mistake. 'Tis true, those who are so rude as to use it in all Conversations, may possibly be so deprav'd themselves, as to fancy every body else as agreeably entertain'd in hearing it as they are in uttering it: But I dare say, any Man or Woman, of real Virtue and Modesty, has as little Taste for such Ribaldry as those Coxcombs have for what is good Sense or true Politeness.

Beau. Good Sense, Sir! Damme, Sir, what do you mean? I would have you think, I know good Sense as well as any Man. Good Sense is a true – a right – a – a – a – Dam it, I wo'nt be so pedantick as to make Definitions: But I can invent a cramp Oath, Sir; drink a smutty Health, Sir; ridicule Priests, laugh at all Religion, and make such a grave Prig as you look just like a Fool, Sir. Now, I take this to be good Sense.

Mast. And I unmov'd can hear such senseless Ridicule, and look upon its Author with an Eye of Pity and Contempt. And I take this to be good Sense.

Beau. Pshaw, pshaw; damn'd Hypocrisy and Affectation; Nothing else, nothing else.

[Exit.Mast. There is Nothing so much my Aversion as a Coxcomb. They are a Ridicule upon humane Nature, and make one almost asham'd to be of the same Species. And, for that Reason, I can't forbear affronting them whenever they fall in my Way. I hope the Ladies will excuse such Behaviour in their Presence.

2 La. Indeed, Sir, I wish we had always somebody to treat them with such Behaviour in our Presence. 'Twould be much more agreeable than their Impertinence.

Enter a Young Gentleman3 Gent. I want a plain Gold Ring, Sir, exactly this Size.

Mast. Then 'tis not for yourself, Sir.

3 Gent. No.

Mast. A Wedding Ring, I presume.

3 Gent. No, Sir, I thank you kindly, that's a Toy I never design to play with. 'Tis the most dangerous Piece of Goods in your whole Shop. People are perpetually doing themselves a Mischief with it. They hang themselves fast together first, and afterwards are ready to hang themselves separately, to get loose again.

1 La. This is but the fashionable Cant. I'll be hang'd if this pretended Railer at Matrimony is not just upon the Point of making some poor Woman miserable. [Aside.]

3 Gent. Well – happy are we whilst we are Children; we can then lay down one Toy and take up another, and please ourselves with Variety: But growing more foolish as we grow older, there's no Toy will please us then but a Wife; and that, indeed, as it is a Toy for Life, so it is all Toys in one. She's a Rattle in a Man's Ears which he cannot throw aside: A Drum that is perpetually beating him a Point of War: A Top which he ought to whip for his Exercise, for like that she is best when lash'd to sleep: A Hobby-Horse for the Booby to ride on when the Maggot takes him: A —

Mast. You may go on, Sir, in this ludicrous Strain, if you please, and fancy 'tis Wit; but, in my Opinion, a good Wife is the greatest Blessing, and the most valuable possession, that Heaven in this Life can bestow. She makes the Cares of the World sit easy, and adds a Sweetness to its Pleasures. She is a Man's best Companion in Prosperity, and his only Friend in Adversity. The carefullest Preserver of his Health, and the kindest Attendant on his Sickness. A faithful Adviser in Distress, a Comforter in Affliction, and a prudent Manager of all his Domestick Affairs.

2 La. [Aside.] Charming Doctrine!

3 Gent. Well, Sir, since I find you so staunch an Advocate for Matrimony, I confess 'tis a Wedding-Ring I want; the Reason why I deny'd it, and of what I said in Ridicule of Marriage, was only to avoid the Ridicule which I expected from you upon it.

Mast. Why that now is just the Way of the World in every Thing, especially, amongst young People. They are asham'd to do a good Action because it is not a fashionable one, and in Compliance with Custom act contrary to their own Consciences. They displease themselves to please the Coxcombs of the World, and chuse rather to be Objects of divine Wrath than humane Ridicule.

3 Gent. 'Tis very true, indeed. There is not one Man in Ten Thousand that dare be virtuous for Fear of being singular. 'Tis a Weakness which I have hitherto been too much guilty of my self; but for the future I am resolv'd upon a more steady Rule of Action.

Mast. I am very glad of it. Here's your Ring, Sir. I think it comes to about a Guinea.

3 Gent. There's the Money.

Mast. Sir, I wish you all the Joy that a good Wife can give you.

3 Gent. I thank you, Sir.

[Exit.1 La. Well, Sir, but, after all, don't you think Marriage a Kind of a desperate Venture?

Mast. It is a desperate Venture, Madam, to be sure. But, provided there be a tolerable Share of Sense and Discretion on the Man's part, and of Mildness and Condescension on the Woman's, there is no danger of leading as happy and as comfortable a Life in that State as in any other.

Enter a fourth Lady4 Lady. I want a Mask, Sir, Have you got any?

Mast. No, Madam, I have not one indeed. The People of this Age are arriv'd to such perfection in the Art of masking themselves, that they have no Occasion for any Foreign Disguises at all. You shall find Infidelity mask'd in a Gown and Cassock; and wantonness and immodesty under a blushing Countenance. Oppression is veil'd under the Name of Justice, and Fraud, and Cunning under that of Wisdom. The Fool is mask'd under an affected Gravity, and the vilest Hypocrite under the greatest Professions of Sincerity. The Flatterer passes upon you under the Air of a Friend; and he that now huggs you in his Bosom, for a Shilling would cut your Throat. Calumny and Detraction impose themselves upon the World for Wit, and an eternal Laugh wou'd fain be thought Good-nature. An humble Demeaner is assum'd from a Principle of Pride, and the Wants of the Indigent relieved out of Ostentation. In short, Worthlessness and Villany are oft disguis'd and dignified in Gold and Jewels, whilst Honesty and Merit lie hid under Raggs and Misery. The whole World is in a Mask, and it is impossible to see the natural Face of any one Individual.

4 Lady. That's a Mistake, Sir, you your self are an Instance, that no Disguise will hide a Coxcomb; and so your humble Servant.

Mast. Humph! – Have I but just now been exclaiming against Coxcombs, and am I accused of being one my self? Well – we can none of us see the ridiculous Part of our own Characters. Could we but once learn to criticize ourselves; and to find out and expose to our selves our own weak Sides, it would be the surest Means to conceal them from the Criticism of others. But I would fain hope I am not a Coxcomb, methinks, whatever I am else.

Gent. I suppose you have said something which her Conscience would not suffer her to pass over without making the ungrateful Application to herself, and that, as it often happens, instead of awaking in her a Sense of her Fault, has only serv'd to put her in a Passion.

Mast. May be so indeed. At least I am willing to think so.

Enter an old ManO. M. I want a pair of Spectacles, Sir.

Mast. Do you please to have 'em plain Tortoise-shell, or set in Gold or Silver?

O. M. Pho! Do you think I buy Spectacles as your fine Gentlemen buy Books? If I wanted a pair of Spectacles only to look at, I would have 'em fine ones; but as I want them to look with, do ye see, I'll have 'em good ones.

Mast. Very well, Sir. Here's a pair I'm sure will please you. Thro' these Spectacles all the Follies of Youth are seen in their true Light. Those Vices which to the strongest youthful Eyes appear in Characters scarce legible, are thro' these Glasses discern'd with the greatest Plainness. A powder'd Wig upon an empty Head, attracts no more respect thro' these Opticks than a greasy Cap; and the Lac'd Coat of a Coxcomb seems altogether as contemptible as his Footman's Livery.

O. M. That indeed is showing things in their true Light.

Mast. The common Virtue of the World appears only a Cloak for Knavery; and it's Friendships no more than Bargains of Self-Interest. In short, he who is now passing away his Days in a constant Round of Vanity, Folly, Intemperance, and Extravagance, when he comes seriously to look back upon his past Actions, thro' these undisguising Opticks, will certainly be convinc'd, that a regular Life, spent in the Study of Truth and Virtue, and adorn'd with Acts of Justice, Generosity, Charity, and Benevolence, would not only have afforded him more Delight and Satisfaction in the present Moment, but would likewise have rais'd to his Memory a lasting Monument of Fame and Honour.

O. M. Humph! 'Tis very true; but very odd that such serious Ware should be the Commodity of a Toy-shop. [Aside.] Well, Sir, and what's the Price of these extraordinary Spectacles?

Mast. Half a Crown.

O. M. There's your Money.

[Exit.Enter a fourth young Gentleman4 Gent. I want a small pair of Scales.

Mast. You shall have them, Sir.

4 Gent. Are they exactly true?

Mast. The very Emblem of Justice, Sir, a Hair will turn 'em. [Ballancing the Scales.]

4 Gent. I would have them true, for they must determine some very nice statical Experiments.

Mast. I'll engage they shall justly determine the nicest Experiments in Staticks, I have try'd them my self in some uncommon Subjects, and have prov'd their Goodness. I have taken a large Handful of Great Men's Promises, and put into one end; and lo! the Breath of a Fly in the other has kick'd up the Beam. I have seen four Peacock's Feathers, and the four Gold Clocks in Lord Tawdry's Stockings, suspend the Scales in Equilibrio. I have found by Experiment, that the Learning of a Beau, and the Wit of a Pedant are a just Counterpoise to each other. That the Pride and Vanity of any Man are in exact Proportion to his Ignorance. That a Grain of Good-nature will preponderate against an Ounce of Wit; a Heart full of Virtue against a Head full of Learning; an a Thimble full of Content against a Chest full of Gold.

4 Gent. This must be a very pretty Science, I fancy.

Mast. It would be endless to enumerate all the Experiments that might be made in these Scales; but there is one which every Man ought to be appriz'd of; and that is, that a Moderate Fortune, enjoy'd with Content, Freedom, and Independency will turn the Scales against whatever can be put in the other End.

4 Gent. Well, this is a Branch of Staticks, which I must own I had but little Thoughts of entering into. However I begin to be persuaded, that to know the true Specifick Gravity of this Kind of Subjects, is of infinitely more Importance than that of any other Bodies in the Universe.

Mast. It is indeed. And that you may not want Encouragement to proceed in so useful a Study, I will let you have the Scales for Ten Shillings. If you make a right Use of them, they will be worth more to you than Ten Thousand Pounds.

4 Gent. I confess I am struck with the Beauty and Usefulness of this Kind of moral Staticks, and believe I shall apply myself to make Experiments with great Delight. There's your Money, Sir: You shall hear shortly what Discoveries I make; in the mean Time, I am your humble Servant.

[Exit.Mast. Sir, I am yours.

Enter a second Old Man2 Old Man. Sir, I understand you deal in Curiosities. Have you any Thing in your Shop, at present, that's pretty and curious?

Mast. Yes, Sir, I have a great many Things. But the most ancient Curiosity I have got, is a small Brass Plate, on which is engrav'd the Speech which Adam made to his Wife, on their first Meeting, together with her Answer. The Characters, thro' Age, are grown unintelligible; but for that 'tis the more to be valued. What is remarkable in this ancient Piece is, that Eve's Speech is about three Times as long as her Husband's. I have a Ram's Horn, one of those which help'd to blow down the Walls of Jericho. A Lock of Sampson's Hair, tied up in a Shred of Joseph's Garment. With several other Jewish Antiquities, which I purchas'd of that People at a very great Price. Then I have the Tune which Orpheus play'd to the Devil, when he charm'd back his Wife.

Gent. That was thought to be a silly Tune, I believe, for no Body has over car'd to learn it since.

Mast. Close cork'd up in a Thumb Phial, I have some Drops of Tears which Alexander wept, because he could do no more Mischief. I have a Snuff-box made out of the Tub in which Diogenes liv'd, and took Snuff at all the World. I have the Net in which Vulcan caught his Spouse and her Gallant; but our modern Wives are now grown so exceeding chaste, that there has not been an Opportunity of casting it these many Years.

Gent. [Aside to the Ladies.] Some would be so malicious now as instead of chaste to think he meant cunning.

Mast. I have the Pitch Pipe of Gracchus, the Roman Orator, who, being apt, in Dispute, to raise his Voice too high, by touching a certain soft Note in this Pipe, would regulate and keep it in a moderate Key.

2 La. Such a Pipe as that, if it could be heard, would be very useful in Coffee-houses, and other publick Places of Debate and modern Disputation.

Gent. Yes, Madam, and, I believe, many a poor Husband would be glad of such a Regulator of the Voice in his own private Family too.

Mast. There you was even with her, Sir. But the most valuable Curiosity I have, is a certain hollow Tube, which I call a Distinguisher; contriv'd with such Art, that, when rightly applied to the Ear, it obstructs all Falshood, Nonsence, and Absurdity, from striking upon the Tympanum: Nothing but Truth and Reason can make the least Impression upon the Auditory Nerves. I have sate in a Coffee-house sometimes, for the Space of Half an Hour, and amongst what is generally call'd the best Company, without hearing a single word. At a Dispute too, when I could perceive, by the eager Motions of both Parties, that they made the greatest Noise, I have enjoy'd the most profound Silence. It is a very useful Thing to have about one, either at Church or Play-house, or Westminster-hall; at all which Places a vast Variety both of useful and diverting Experiments may be made with it. The only Inconvenience attending it is, that no Man can make himself a compleat Master of it under Twenty Years close and diligent Practice: And that Term of Time it best commenc'd at Ten or Twelve Years old.

Gent. That indeed is an Inconvenience that will make it not every Body's Money. But one would think those Parents who see the Beauty and the Usefulness of Knowledge, Virtue, and a distinguishing Judgment, should take particular Care to engage their Children early in the Use and Practice of such a Distinguisher, whilst they have Time before them, and no other Concerns to interrupt their Application.

Mast. Some few do. But the Generality are so entirely taken up with the Care of little Master's Complexion, his Dress, his Dancing, and such like Effeminacies, that they have not the least Regard for any internal Accomplishments whatsoever. They are so far from teaching him to subdue his Passions, that they make it their whole Business to gratify them all.

2 Old Man. Well, Sir; to some People these may be thought curious Things, perhaps, and a very valuable Collection. But, to confess the Truth, these are not the Sort of curious Things I wanted. Have you no little Box, representing a wounded Heart, on the Inside the Lid? Nor pretty Ring, with an amorous Poesy? Nothing of that Sort, which is pretty and not common, in your Shop?

Mast. O yes, Sir! I have a very pretty Snuff-box here, on the inside of the Lid, do ye see, is a Man of threescore and ten acting the Lover, and hunting like a Boy after Gewgaws and Trifles, to please a Girl with.

2 O. M. Meaning me, Sir? Do ye banter me, Sir?

Mast. If you take it to your self, Sir, I can't help it.

2 O. M. And is a Person of my Years and Gravity to be laugh'd at, then?

Mast. Why, really, Sir, Years and Gravity do make such Childishness very ridiculous, I can't help owning. However, I am very sorry I have none of those curious Trifles for your Diversion, but I have delicate Hobby Horses and Rattles if you please.

2 O. M. By all the Charms of Araminta, I will revenge this affront.

[Exit.Gent. Ha, ha, ha! how contemptible is Rage in Impotence! But pray, Sir, don't you think this kind of Freedom with your Customers detrimental to your Trade?

Mast. No, no, Sir, the odd Character I have acquir'd by this rough kind of Sincerity and plain Dealing; together with the whimsical Humour of moralizing upon every Trifle I sell; are the Things, which by raising Peoples Curiosity, furnish me with all my Customers: And it is only Fools and Coxcombs I am so free with.

La. And in my Opinion, you are in the Right of it. Folly and Impertinence ought always to be the Objects of Satire and Ridicule.

Gent. Nay, upon second Thoughts, I don't know but this odd turn of Mind, which you have given your self, may not only be entertaining to several of your Customers, but, perhaps, very much so to your self.

Mast. Vastly so, Sir. It very often helps me to Speculations infinitely agreeable. I can sit behind this Counter, and fancy my little Shop, and the Transactions of it, an agreeable Representation of the grand Theater of the World. When I see a Fool come in here, and throw away 50 or 100 Guineas for a Trifle that is not really worth a Shilling, I am sometimes surpriz'd: But when I look out into the World, and see Lordships and Manors barter'd away for gilt Coaches and Equipage; an Estate for a Title; and an easy Freedom in Retirement for a servile Attendance in a Crowd; when I see Health with great eagerness exchang'd for Diseases, and Happiness for a Game at Hazard; my Wonder ceases. Surely the World is a great Toy-shop, and all it's Inhabitants run mad for Rattles. Nay, even the very wisest of us, however, we may flatter our selves, have some Failing or Weakness, some Toy or Trifle, that we are ridiculously fond of. Yet, so very partial are we to our own dear selves, that we over-look those Miscarriages in our own Conduct, which we loudly exclaim against in that of others; and, tho' the same Fool's Turbant fits us all,

You say that I, I say that You are He,And each Man swears "The Cap's not made for me."Gent. Ha, ha! 'Tis very true, indeed. But I imagine you now begin to think it Time to shut up Shop. Ladies, do ye want any Thing else?

1 La. No, I think not. If you please to put up that Looking-glass; and the Perspective, I will pay you for them.

Gent. Well, Madam, how do you like this whimsical Humourist?

1. La. Why, really, in my Opinion, the Man's as great a Curiosity himself, as any Thing he has got in his Shop.

Gent. He is so indeed. I think we have heard a great Deal of Folly very justly ridicul'd.

In this gay thoughtless Age He'as found a Way,In trifling Things just Morals to convey.'Tis his at once to please and to reform,And give old Satire a new Pow'r to charm.And, would you guide your Lives and Actions right,Think on the Maxims you have heard to Night.FINISDramatis Personæ

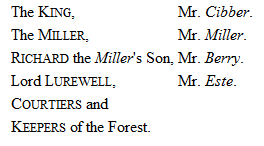

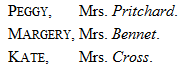

MEN

THE KING AND THE MILLER

SCENE, Sherwood Forest Enter several Courtiers as lost1 Courtier. It is horrid dark! and this Wood I believe has neither End nor Side.

4 C. You mean to get out at, for we have found one in you see.

2 C. I wish our good King Harry had kept nearer home to hunt; in my Mind the pretty, tame Deer in London make much better Sport than the wild ones in Sherwood Forest.

3 C. I can't tell which Way his Majesty went, nor whether any-body is with him or not, but let us keep together pray.

4 C. Ay, ay, like true Courtiers, take Care of ourselves whatever becomes of Master.

2 C. Well, it's a terrible Thing to be lost in the Dark.

4 C. It is. And yet it's so common a Case, that one would not think it should be at all so. Why we are all of us lost in the Dark every Day of our Lives. Knaves keep us in the Dark by their Cunning, and Fools by their Ignorance. Divines lose us in dark Mysteries; Lawyers in dark Cases; and Statesmen in dark Intrigues: Nay, the Light of Reason, which we so much boast of, what is it but a Dark-Lanthorn, which just serves to prevent us from running our Nose against a Post, perhaps; but is no more able to lead us out of the dark Mists of Error and Ignorance, in which we are lost, than an Ignis fatuus would be to conduct us out of this Wood.