полная версия

полная версияStories of Useful Inventions

The methods of warming the house and cooking the food which have just been described were certainly crude and inconvenient, but it was thousands of years before better methods were invented. The long periods of savagery and barbarism passed and the period of civilization was ushered in, but civilization did not at once bring better stoves. Neither the ancient Egyptians nor the ancient Greeks knew how to heat a house comfortably and conveniently. All of them used the primitive stove – a fire on the floor and a hole in the roof. In the house of an ancient Greek there was usually one room which could be heated when there was need, and this was called the "black-room" (atrium) – black from the soot and smoke which escaped from the fire on the floor.

But we must not speak harshly of the ancients because they were slow in improving their methods of heating, for in truth the modern world has not done as well in this direction as might have been expected. In a book of travels written only sixty years ago may be found the following passage: "In Normandy, where the cold is severe and fire expensive, the lace-makers, to keep themselves warm and to save fuel, agree with some farmer who has cows in winter quarters to be allowed to carry on their work in the society of the cattle. The cows would be tethered in a long row on one side of the apartment, and the lace-makers sit on the ground on the other side with their feet buried in the straw." Thus the lace-makers kept themselves warm by the heat which came from the bodies of the cattle; the cows, in other words, served as stoves. This barbarous method of heating was practised in some parts of France less than sixty years ago.

FIG. 3. – A ROMAN BRAZIER.

The ancient peoples around the Mediterranean may be excused for not making great progress in the art of heating, for their climate was so mild that they seldom had use for fire in the house. Nevertheless there was in use among these people an invention which has in the course of centuries developed into the stove of to-day. This was the brazier, or warming-pan (Fig. 3). The brazier was filled with burning charcoal and was carried from room to room as it was needed. The unpleasant gases which escaped from the charcoal were made less offensive, but not less unhealthy, by burning perfumes with the fuel. The brazier has never been entirely laid aside. It is still used in Spain and in other warm countries where the necessity for fire is rarely felt.

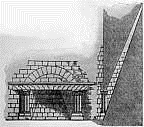

FIG. 4. – A ROMAN HYPOCAUST.

The brazier satisfied the wants of Greece, but the colder climate of Rome required something better; and in their efforts to invent something better, the ancient Romans made real progress in the art of warming their houses. They built a fire-room – called a hypocaust– in the cellar, and, by means of pipes made of baked clay, they connected the hypocaust with different parts of the house (Fig. 4). Heat and smoke passed up together through these pipes. The poor ancients, it seems, were forever persecuted by smoke. However, after the wood in the hypocaust was once well charred, the smoke was not so troublesome. The celebrated baths (club-rooms) of ancient Rome were heated by means of hypocausts with excellent results. Indeed, the hypocaust had many of the features and many of the merits of our modern furnace. Its weak feature was that it had no separate pipe to carry away the smoke. But as there were no chimneys yet in the world, it is no wonder there was no such pipe.

The Romans made quite as much progress in the art of cooking as they did in the art of heating. Perhaps the world has never seen more skilful cooks than those who served in the mansions of the rich during the period of the Roman Empire (27 B.C. -476 A.D.). In this period the great men at Rome abandoned their plain way of living and became gourmands. One of them wished for the neck of a crane, that he might enjoy for a longer time his food as it descended. This demand for tempting viands developed a race of cooks who were artists in their way. Upon one occasion a king called for a certain kind of fish. The fish could not be had, but the cook was equal to the emergency. "He cut a large turnip to the perfect imitation of the fish desired, and this he fried and seasoned so skilfully that his majesty's taste was exquisitely deceived, and he praised the root to his guests as an excellent fish." Such excellent cooking could not be done on a primitive stove, and along with the improvements in the art of cooking, there was a corresponding improvement at Rome in the art of stove-making.

When Rome fell (476 A.D.), many of the best features of her civilization perished with her. Among the things that were lost to the world were the Roman methods of cooking and heating. When the barbarians came in at the front door, the cooks fled from the kitchen. The hardy northerners had no taste for dainty cooking. Hypocausts ceased to be used, and were no longer built. For several hundred years, in all the countries of Europe, the fireplace was located, as of old, on the floor in the center of the room, while the smoke was allowed to pass out through a hole in the roof.

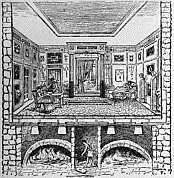

FIG. 5. – A CHIMNEY AND FIREPLACE IN AN OLD ENGLISH CASTLE.

The eleventh century brought a great improvement in the art of heating, and the improvement came from England. About the time of the Conquest (1066) a great deal of fighting was done on the roofs of English fortresses, and the smoke coming up through the hole in the center of the roof proved to be troublesome to the soldiers. So the fire was moved from the center of the floor to a spot near an outside wall, and an opening was made in the wall just above the fire, so that the smoke could pass out. Here was the origin of the chimney. Projecting from the wall above the fire was a hood, which served to direct the smoke to the opening. At first the opening for the smoke extended but a few feet from the fire, but it was soon found that the further up the wall the opening extended the better was the draft. So the chimney was made to run diagonally up the wall as far as possible. The next and last step in the development of the chimney was to make a recess in the wall as a fireplace, and to build a separate structure of masonry – the chimney – for the smoke. By the middle of the fourteenth century chimneys were usually built in this way (Fig. 5). As the fireplace and chimney cleared the house of soot and smoke, they grew in favor rapidly. By the end of the fifteenth century they were found in the homes of nearly all civilized people.

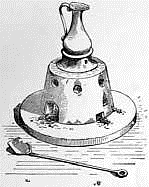

FIG. 6. – A STOVE OF THE MIDDLE AGES.

The open fireplace was always cheerful, and it was comfortable when you were close to it; but it did not heat all parts of the room equally. That part next to the fireplace might be too warm for comfort, while in another part of the room it might be freezing. About the end of the fifteenth century efforts were made to distribute heat throughout the room more evenly. These efforts led to the invention of the modern stove. We have learned that the origin of the stove is to be sought in the ancient brazier. In the middle ages the brazier in France took on a new form. Here was a fire-box (Fig. 6) with openings at the bottom for drafts of air and arrangements at the top for cooking things. This French warming-pan (réchaud) was the connecting-link between the ancient brazier and the modern stove. All it lacked of being a stove was a pipe to carry off the smoke, and this was added by a Frenchman named Savot, about two hundred years ago. We owe the invention of the chimney to England, but for the stove we are indebted to France. The Frenchman built an iron fire-box, with openings for drafts, and connected the box with the chimney by means of an iron flue or pipe. Here was a stove which could be placed in the middle of the room, or in any part of the room where it was desirable, and which would send out its heat evenly in all directions.

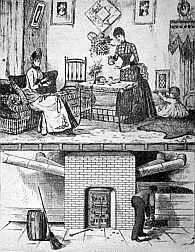

FIG. 7. – THE MODERN STOVE.

FIG. 8. – AN OLD-FASHIONED FIREPLACE AND OVEN.

The first stoves were, of course, clumsy and unsatisfactory; but inventors kept working at them, making them better both for cooking and for heating. By the middle of the nineteenth century the stove was practically what it is to-day (Fig. 7). Stoves proved to be so much better than fireplaces, that the latter were gradually replaced in large part by the former. Our affection, however, for a blazing fire is strong, and it is not likely that the old-fashioned fireplace (Fig. 8) will ever entirely disappear.

The French stove just described is intended to heat only one room. If a house with a dozen rooms is to be heated, a dozen stoves are necessary. About one hundred years ago there began to appear an invention by which a house of many rooms could be heated by means of one stove. This invention was the furnace. Place in the cellar a large stove, and run pipes from the stove to the different rooms of the house, and you have a furnace (Fig. 9). Doubtless we got our idea of the furnace from the Roman hypocaust, although the Roman invention had no special pipe for the smoke. The first furnaces sent out only hot air, but in recent years steam or hot water is sent out through the pipes to radiators, which are simply secondary stoves set up in convenient places and at a distance from the source of the heat, the furnace in the cellar. Furnaces were invented for the purpose of heating large buildings, but they are now used in ordinary dwellings.

FIG. 9. – A MODERN FURNACE.

In its last and most highly developed form, the stove appears not only without dust and smoke, but also without even a fire in the cellar. The modern electric stove, of course, is meant. Pass a slight current of electricity through a piece of platinum wire, and the platinum becomes hot. You have made a diminutive electric stove. Increase the strength of your current and pass it through something which offers greater resistance than the platinum, and you get more heat. The electric stove is a new invention, and at present it is too expensive for general use, although the number of houses in which it is used is rapidly increasing, and in time it may drive out all other kinds of stoves. It will certainly drive all of them out if the cost of electricity shall be sufficiently reduced; for it is the cleanest, the healthiest, the most convenient, and the most easily controlled of stoves.

THE LAMP

Next to its usefulness for heating and cooking, the greatest use of fire is to furnish light to drive away darkness. Man is not content, like birds and brutes, to go to sleep at the setting of the sun. He takes a part of the night-time and uses it for work or for travel or for social pleasures, or for the improvement of his mind, and in this way adds several years to life. He could not do this if he were compelled to grope in darkness. When the great source of daylight disappears he must make light for himself, for the sources of night-light – the moon and stars and aurora borealis and lightning – are not sufficient to satisfy his wants. In this chapter we shall follow man in his efforts to conquer darkness, and we shall have the story of the lamp.

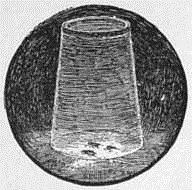

FIG. 1. – A FIREFLY LAMP.

We may begin the story with an odd but interesting kind of lamp. The firefly or lightning-bug which we see so often in the summer nights was in the earliest time brought into service and made to shed its light for man. Fireflies were imprisoned in a rude box – in the shell of a cocoanut, perhaps, or in a gourd – and the light of their bodies was allowed to shoot out through the numerous holes made in the box. We must not despise the light given out by these tiny creatures. "In the mountains of Tijuca," says a traveler, "I have read the finest print by the light of one of these natural lamps (fireflies) placed under a common glass tumbler (Fig. 1), and with distinctness I could tell the hour of the night and discern the very small figures which marked the seconds of a little Swiss watch."

FIG. 2. – A BURNING STICK WAS THE FIRST LAMP.

Although fireflies have been used here and there by primitive folk, they could hardly have been the first lamp. Man's battle with darkness really began with the torch, which was lighted at the fire in the cave or in the wigwam and kept burning for purposes of illumination. A burning stick was the first lamp (Fig. 2). The first improvement in the torch was made when slivers or splinters of resinous or oily wood were tied together and burned. We may regard this as a lamp which is all wick. This invention resulted in a fuller and clearer light, and one that would burn longer than the single stick. A further improvement came when a long piece of wax or fatty substance was wrapped about with leaves. This was something like a candle, only the wick (the leaves) was outside, and the oily substance which fed the wick was in the center.

FIG. 3. – THE CANDLE.

In the course of time it was discovered that it was better to smear the grease on the outside of the stick, or on the outside of whatever was to be burned; that is, that it was better to have the wick inside. Torches were then made of rope coated with resin or fat, or of sticks or splinters smeared with grease; here the stick resembled the wick of the candle as we know it to-day, and the coating of fat corresponded to the tallow or paraffin. Rude candles made of oiled rope or of sticks smeared with fat were invented in primitive times, and they continued to be used for thousands of years after men were civilized. In the dark ages – and they were dark in more senses than one – torch-makers began to wrap the central stick first with flax or hemp and then place around this a thick layer of fat. This torch gave a very good light, but about the time of Alfred the Great (900 A.D.) another step was taken: the central stick was left out altogether, and the thick layer of fat or wax was placed directly around the wick of twisted cotton. All that was left of the original torch – the stick of wood – was gone. The torch had developed into the candle (Fig. 3). The candles of to-day are made of better material than those of the olden time, and they are much cheaper; yet in principle they do not differ from the candles of a thousand years ago.

FIG. 4. – A SHELL FILLED WITH OIL AND USED AS A LAMP.

I have given the development of the candle first because its forerunner, the torch, was first used for lighting. But it must not be forgotten that along with the torch there was used, almost from the beginning, another kind of lamp. Almost as soon as men discovered that the melted fat of animals would burn easily – and that was certainly very long ago – they invented in a rude form the lamp from which the lamp of to-day has been evolved. The cavity of a shell (Fig. 4) or of a stone, or of the skull of an animal, was filled with melted fat or oil, and a wick of flax or other fibrous material was laid upon the edge of the vessel. The oil or grease passed up the wick by capillary action,6 and when the end of the wick was lighted it continued to burn as long as there were both oil and wick. This was the earliest lamp. As man became more civilized, instead of a hollow stone or a skull, an earthen saucer or bowl was used. Around the edge of the bowl a gutter or spout was made for holding the wick. In the lamp of the ancient Greeks and Romans the reservoir which held the oil was closed, although in the center there was a hole through which the oil might be poured. Sometimes one of these lamps would have several spouts or nozzles. The more wicks a lamp had, of course, the more light it would give. There is in the museum at Cortona, in Italy, an ancient lamp which has sixteen nozzles. This interesting relic (Fig. 5) was used in a pagan temple in Etruria more than twenty-five hundred years ago.

FIG. 5. – AN ETRUSCAN LAMP 2500 YEARS OLD.

FIG. 6. – AN ANCIENT LAMP.

Lamps such as have just been described were used among the civilized peoples of the ancient world, and continued to be used through the Middle Ages far into modern times. They were sometimes very costly and beautiful (Fig. 6), but they never gave a good light. They sent out an unpleasant odor, and they were so smoky that they covered the walls and furniture with soot. The candle was in every way better than the ancient lamp, and after the invention of wax tapers – candles made of wax – in the thirteenth century, lamps were no longer used by those who could afford to buy tapers. For ordinary purposes and ordinary people, however, the lamp continued to do service, but it was not improved. The eighteenth century had nearly passed, and the lamp was still the unsatisfactory, disagreeable thing it had always been.

FIG. 7. – AN ARGAND LAMP.

Late in the eighteenth century the improvement came. In 1783 a man named Argand, a Swiss physician residing in London, invented a lamp that was far better than any that had ever been made before. What did Argand do for the lamp? Examine an ordinary lamp in which coal-oil is burned. The chimney protects the flame from sudden gusts of wind and also creates a draft of air,7 just as the fire-chimney creates a draft. Argand's lamp (Fig. 7) was the first to have a chimney. Look below the chimney and you will see open passages through which air may pass upward and find its way to the wick. Notice further that as this draft of air passes upward it is so directed that, when the lamp is burning, an extra quantity of air plays directly upon the wick. Before Argand, the wick received no supply of air. Now notice – and this is very important – that the wick of our modern lamp is flat or circular, but thin. The air in abundance plays upon both sides of the thin wick, and burns it without making smoke. Smoke is simply half-burned particles (soot) of a burning substance. The particles pass off half-burned because enough air has not been supplied. Now Argand, by making the wick thin and by causing plenty of air to rush into the flame, caused all the wick to be burned and thereby caused it to burn with a white flame.

After the invention of Argand, the art of lamp-making improved by leaps and by bounds. More progress was made in twenty years after 1783 than had been made in twenty centuries before. New burners were invented, new and better oils were used, and better wicks made. But all the new kinds of lamps were patterned after the Argand. The lamp you use at home may not be a real Argand, but it is doubtless made according to the principles of the lamp invented by the Swiss physician in 1783.

Soon after Argand invented his lamp, William Murdock, a Scottish inventor, showed the world a new way of lighting a house. It had long been known that fat or coal, when heated, gives off a vapor or gas which burns with a bright light. Indeed, it is always a gas that burns, and not a hard substance. In the candle or in the lamp the flame heats the oil which comes up to it through the wick and thus causes the oil to give off a gas. It is this gas that burns and gives the light. Now Murdock, in 1797, put this principle to a good use. He heated coal in a large vessel, and allowed the gas which was driven off to pass through mains and tubes to different parts of his house. Wherever he wanted a light he let the gas escape at the end of the tube (Fig. 8) in a small jet and lighted it. Here was a lamp without a wick. Murdock soon extended his gas-pipes to his factories, and lighted them with gas. As soon as it was learned how to make gas cheaply, and conduct it safely from house to house, whole cities were rescued from darkness by the new illuminant. A considerable part of London was lighted by gas in 1815. Baltimore was the first city in the United States to be lighted by gas. This was in 1821.

FIG. 8. – THE GAS JET.

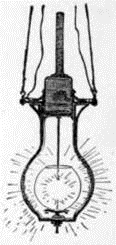

FIG. 9. – AN EARLY ARC LAMP.

The gas-light proved to be so much better than even the best of lamps, that in towns and cities almost everybody who could afford to do so laid aside the old wick-lamp and burned gas. About 1876, however, a new kind of light began to appear. This was the electric light. The powerful arc light (Fig. 9), made by the passage of a current of electricity between two carbon points, was the first to be invented. This gave as much light as a hundred gas-jets or several hundred lamps. Such a light was excellent for lighting streets, but its painful glare and its sputtering rendered it unfit for use within doors. It was not long, however, before an electric light was invented which could be used anywhere. This was the famous Edison's incandescent or glow lamp (Fig. 10), which we see on every hand. Edison's invention is only a few years old, yet there are already more than thirty million incandescent lamps in use in the United States alone.

FIG. 10. – AN INCANDESCENT ELECTRIC LIGHT.

The torch, the candle, the lamp, the gas-light, the electric light, – these are the steps of the development of the lamp. And how marvelous a growth it is! How great the triumph over darkness! In the beginning a piece of wood burns with a dull flame, and fills the dingy wigwam or cave with soot and smoke; now, at the pressure of a button, the house is filled with a light that rivals the light of day, with not a particle of smoke or soot or harmful gas. Are there to be further triumphs in the art of lighting? Are we to have a light that shall drive out the electric light? Only time can tell.

THE FORGE

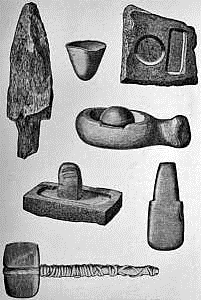

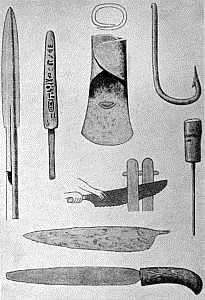

After men had learned how to use fire for cooking and heating and lighting they slowly learned how to use it when working with metals. In the earliest times metals were not used. For long ages stone was the only material that man could fashion and shape to his use. During this period, sometimes called the "stone age," weapons were made of stone; dishes and cooking utensils were made of stone; and even the poor, rude tools of the age were made of stone (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1. – IMPLEMENTS OF THE STONE AGE.

FIG. 2. – IMPLEMENTS OF THE BRONZE AGE.

In the course of time man learned how to make his implements and weapons of metals as well as of stone. It is generally thought that bronze was the first metal to be used and that the "stone age" was followed directly by the "bronze age," a period when all utensils, weapons, and tools were made of bronze (Fig. 2). It is easy to believe that bronze was used before iron, for bronze is made of a mixture of tin and copper and these two metals are often found in their pure or natural state. Whenever primitive man, therefore, found pieces of pure copper and tin, he could take the two metals and by melting them could easily mix them and make bronze of them. This bronze he could fashion to his use. There is no doubt that he did this at a very early age. In nearly all parts of the world there are proofs that in primitive times, many articles were made of bronze.