полная версия

полная версияStories of Useful Inventions

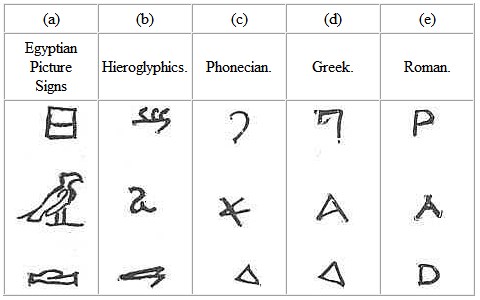

Now that its origin has been explained, the story of the alphabet may be rapidly told. Indeed, its whole history can be learned from Figure 5. In column (a) are the three Egyptian picture-signs referred to above. Column (b) shows how the rapid writing of the priests reduced the old hieroglyphics to script;

FIG. 5. – SHOWING THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE THREE LETTERS, P, A, AND D.

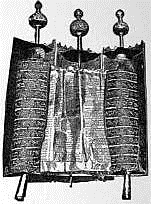

We must look to Egypt for the origin of the material form of our book as well as for the origin of our alphabetical characters. Before history had dawned the Egyptians had covered over with their writing nearly all the available surface on their pyramids and in their temples. At a time too far back for a date necessity seems to have compelled them to seek a substitute for stone. This they found in the papyrus plant, which grew in great luxuriance in the valley of the Nile. They placed side by side strips of the pith of the papyrus, and across these at right angles they placed another layer of strips. The two layers were then glued together and pressed until a smooth surface was formed. This made one sheet. To make a book a number of sheets were fastened together end to end. When in book form the papyrus was wound around a stick and kept in the form of a roll, a volume (Fig. 6). The roll was usually eight or ten inches wide, but its length might be upward of a hundred feet. This papyrus roll was the parent of our modern paper book, as the word papyrus is the original of our word paper. The pen used in writing upon papyrus was a split reed (calamus), and the ink a mixture of soot and gum.

FIG. 6. – AN ANCIENT VOLUME.

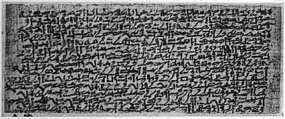

FIG. 7. – THE OLDEST BOOK IN THE WORLD. WRITTEN NEARLY 5,000 YEARS AGO.

The most ancient volume in the world is an Egyptian papyrus (Fig. 7) now in the National Library of France. It was written nearly 5,000 years ago by an aged sage and contains precepts of right living. In this oldest of volumes we find this priceless gem:

"If thou art become great, if after being in poverty thou hast amassed riches and art become the first in the city, if thou art known for thy wealth and art become a great lord, let not thy heart become proud, for it is God who is the author of them for thee."

In Assyria and in other ancient countries of Central Asia letters were engraved on cylinders and these were rolled upon slabs of soft clay, making an impression of the raised letters, just as we make an impression with the seal of a ring. In the ruins of the cities of Assyria these old clay books may be found by the cart-load. The Assyrian cylinder was really the first printing press. In ancient Greece and Rome wooden tablets within which was spread a thin layer of wax were used as a writing surface in schools and in the business world. The writing on the wax was done with a sharp-pointed instrument of bone or iron called the stylus. But next to papyrus the most important writing material of antiquity was parchment, or the prepared skin of young calves and kids. The invention of parchment is said to have been due to the literary ambitions of two kings, the king of Persia and the king of Egypt. The king of Pergamus (250 B.C.) wishing to have the finest and largest library in the world was consuming enormous quantities of papyrus. The king of Egypt, who also wished to have the finest library in the world, in order to cripple the plans of his literary rival, issued a command forbidding the exportation of papyrus from Egypt. The king of Pergamus, being unable to get papyrus except from Egypt, caused the skins of sheep to be prepared, and on these skins books for his library continued to be written. The prepared skins received the name of pergamena, because they were made in Pergamus, and from pergamena we get the word parchment. This is the story that has come down to us to explain the origin of parchment, but it cannot be accepted as wholly true. We know very well that the Old Testament was written in gold on a roll of skins long before there was a king of Pergamus. Indeed, writing was done on skins as far back as the picture-writing period.

After the invention of the alphabet and of paper (papyrus) books multiplied as never before. "Of making many books there is no end," exclaimed Solomon a thousand years before the Christian era. Greece in her early day was slow to make books, but after she learned from the Phœnicians (800 B.C.) how to use an alphabet she made up for lost time. In 600 B.C. there was a public library at Athens, and 200 years later the Greeks had written more good books than all the other countries in the world combined.

But the most productive of ancient book-makers were the Romans. In Rome publishing houses were flourishing in the time of Cicero (50 B.C.). Atticus, one of Cicero's best friends, was a publisher. Let us see how a book was made in his establishment. Of course, there were no type-setters or printing-presses. Every book was a manuscript; every word of every copy had to be written with a pen. The writing was sometimes done by slaves trained to write neatly and rapidly. We may imagine 50 or 100 slaves sitting at desks in a room writing to the dictation of the reader. Now if Atticus had ten readers each of whom dictated to 100 slaves it took only two or three days for the publication of 1,000 copies of one of his friend Cicero's books. Of course every copy would not be perfect. The slave would sometimes make blunders and write what the reader did not dictate. But books in our own time are not free of errors. An English poet recently wrote:

"Like dew-drops upon fresh blown roses."In print the first letter of the last word in the line appeared as n instead of r. This mistake disfigured thousands of copies. In the Roman publishing house such a blunder marred only one copy.

You can readily see that by methods just described books could be made in great numbers. And so they were. Slaves were cheap and numerous and the cost of publication was small. It is estimated that a good sized volume in Nero's time (50 A.D.) would sell for a shilling. Books were cheaper in those days than they had ever been before and almost as cheap as they are to-day, perhaps. The Roman world became satiated with reading matter. The poet Martial exclaimed, "Every one has me in his pocket, every one has me in his hand." Books became a drug on the market and could be sold only to grocers for "wrapping up pastry and spices."

FIG. 8. – BOOK-MAKING IN THE MIDDLE AGES.

But a time was to come when books would not be so plentiful and cheap. With the overthrow of Rome (476 A.D.) culture received a blow from which it did not recover for a thousand years. The barbarian invaders of Southern Europe destroyed all the books they could find and caused the writers of books to flee within the walls of the churches. Throughout the Middle Ages nearly all the writing in Europe was done in the religious houses of monks (Fig. 8), and nearly all the books written were of a religious nature. The monks worked with the greatest patience and care upon their manuscripts. They often wrote on vellum (calf-skin parchment) and illuminated the page with beautiful colors and adorned it with artistic figures.

The manuscript volumes of the dark ages were beautiful and magnificent, but their cost was so great that only the most wealthy could buy. A Bible would sometimes cost thousands of dollars. Along in the 14th and 15th centuries Europe began to thirst for knowledge and there arose a demand for cheap books. How could the demand be met? There were now no hordes of intelligent slaves who could be put to work with their pens, and without slave labor the cost of the written book could not be greatly reduced. Invention, as always, came to the rescue and gave the world what it wanted.

In the first place, writing material was made cheaper by the invention of paper-making. The wasp in making its nest had given a hint for paper-making, but man was extremely slow to take the hint. The Chinese had done something in the way of making paper from the bark of trees as early as the first century, but it was not until the middle of the 13th century that paper began to be manufactured in Europe from hemp, rags, linen, and cotton.

FIG. 9.

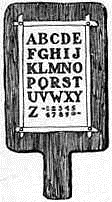

FIG. 10. – A BLOCK PRINT CONTAINING THE ALPHABET USED BY CHILDREN WHEN LEARNING TO READ.

In the second place, printing was invented. On a strip of transparent paper write the word post. Now turn the strip over from right to left and trace the letters on the smooth surface of a block of wood. Remove the paper and you will have the result shown in Figure 9. With a sharp knife cut out the wood from around the letters. Ink the raised letters and press upon them a piece of paper. You have printed the word "post" in precisely the way the first books were printed. In the 13th century fancy designs were engraved on wood and by the aid of ink the figures were stamped on silk and linen. In the 14th century playing cards and books were printed on engraved blocks in the manner the word "post" was printed above. (Fig. 10.) The block-book was the first step in the art of printing.

The block-book decreased the cost of a book, for when a page was once engraved as many impressions could be taken as were wanted, yet it did not meet the necessities of the time. In the middle of the 15th century the desire for reading began to resemble a frenzy and the books that could be got hold of "were as insufficient to slake the thirsty craving for religious and material knowledge as a few rain drops to quench the burning thirst of the traveler in the desert who seeks for long, deep-draughts at copious springs of living water." To meet the demand of the time book-makers everywhere were trying to improve on the block-making process and by the end of the century the book as we have it to-day was being made throughout all Europe.

In what did the improvement consist? First let us call to mind what the book-maker in the early part of the 15th century had to begin with; he had paper, he had printing-ink, he had skill in engraving whole pages for block-books, and he had a rude kind of printing-press. The improvement consisted in this: Instead of engraving a whole page on a block, single letters were engraved on little blocks called types, and when a word or a line or a page was to be printed these types were set in the position desired; in other words, the improvement consisted in the invention of moveable types. The types were first made of wood and afterward of metal.

The great advantage of the moveable types over the block-book is easily seen. A block containing, say, the word "post" is useless except for printing the word post; but divide it into four blocks, each containing a letter: now you can print post, spot, tops, stop, top, sop, sot, pot, so, to and so forth.

The exact date of the invention of moveable types cannot be determined. We can only say that they were first used between 1450 and 1460. Nor can we tell who invented them. The Dutch claim that Lawrence Koster of Harlem (Holland) made some moveable types as early as 1430, and that John Faust, an employee, stole them and carried them to Mayence (Germany), where John Gutenberg learned the secret of printing with them. The Germans claim that Gutenberg was the real inventor. Much can be said in behalf of both claims. What we really know is that the earliest complete book printed on moveable types was a Bible which came from the press of John Gutenberg in 1455.

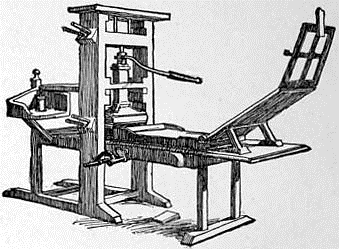

Since 1450 there has been no discovery that has changed the character of the printed volume. There have been wonderful improvements in the processes of making and setting type, and printing-presses (Fig. 11) have become marvels of mechanical skill, but the book of to-day is essentially like the book of four hundred years ago. The tablet of the memory, the knotted cord and notched stick, the uncanny picture-writing, the clumsy picture-sign, the alphabet, the manuscript volume, the printed block-book and the volume before you bring to an end the story of the book.

FIG. 11. – AN EARLY PRINTING PRESS.

THE MESSAGE

Men had not been living together long in a state of society before they found it necessary to communicate with their fellow-men at a distance and in order to do this the message was invented. We have seen (p. 205) that among certain tribes of savages notched sticks bearing messages were sent from one tribe to another. Among the ancient Peruvians the message took the form of the curious looking quipu. After the alphabet had been invented and papyrus had come into use as a writing material, the message took the form of a written document and resembled somewhat the modern letter.

FIG. 1. – A LETTER CARRIER OF ANCIENT EGYPT.

The ancient Egyptians, as we would expect, were the first to make use of the letter in the sending of messages (Fig. 1). The ancient Hebrews were also familiar with the letter as a means of communication. We read in the book of Chronicles how the post went with the letters of the king and his princes throughout all Israel. The word post, as used here and elsewhere in the Bible, signifies a runner, that is, one specially trained to deliver letters or despatches speedily by running. Thus Jeremiah predicted that after the fall of Babylon "one post shall run to meet another and one messenger to meet another to show the King that his city is taken." Although we frequently read of the post in Biblical times we are nowhere told that the ordinary people enjoyed the privileges of the post. In olden times it was only kings and princes and persons of high degree that sent and received letters.

FIG. 2. – AN EGYPTIAN MAIL CART.

In nearly all the countries of antiquity there was an organized postal system which was under the control of the government and which carried only government messages. In Egypt there were postal chariots (Fig. 2) of wonderful lightness designed especially for carrying the letters of the king at the greatest possible speed. In ancient Judea messengers must have traveled very fast, for Job, in his old age, says: "Now my days are swifter than the post, they flee away." In ancient Persia the postal system awakened the admiration of Herodotus. "Nothing mortal," says this old Greek historian, "travels so fast as these Persian messengers. The entire plan is a Persian invention and this is the method of it. Along the whole line of road there are men stationed with horses, the number of stations being equal to the number of days which the journey takes, allowing a man and a horse to each day, and these men will not be hindered from accomplishing at their best speed the distance they will have to go either by snow, or rain, or heat, or by the darkness of night. The first rider delivers the message to the second and the second to the third, and so it is borne from hand to hand along the whole line."

FIG. 3. – A LETTER CARRIER OF ANCIENT GREECE.

The postal system which Herodotus found in Persia was better than the system which existed in his own country for the reason that the Greeks relied upon human messengers rather than upon horses to carry their messages. Young Greeks were specially trained (Fig. 3) as runners for the postal service and Greek history contains accounts of the marvelous endurance and swiftness of those employed to carry messages. After the defeat of the Persians by the Greeks at Marathon (490 B. C.) a runner carried the news southward and did not pause for rest until he reached Athens when he shouted the word "Victory!" and expired, being overcome by fatigue. Another Greek, Phillipides by name, was despatched from Athens to Sparta to ask the Spartans for aid in the war which the Athenians were carrying on against Persia, and the distance between the two cities – about 140 miles – was accomplished by the runner in less than two days.

FIG. 4. – A LETTER CARRIER OF ANCIENT ROME.

But the best postal system of ancient times was the one which was organized by the Romans. As one country after another was brought under the dominion of Rome it became more and more necessary for the Roman government to keep in close touch with all the parts of the vast empire. Accordingly, by the time of Augustus (14 A.D.), there was established throughout the Roman world a fully organized and well-equipped system of posts. Along the magnificent roads which led out from Rome there were built at regular distances stations, or post-houses, where horses and riders were stationed for the purpose of receiving the messages of the government and hurrying them along to the place of their destination. The stations were only five or six miles apart and each station was provided with a large number of horses and riders. By the frequent changes of horses a letter could be hurried along with considerable speed (Fig. 4). "By the help of the relays," says Gibbon, "it was easy to travel a hundred miles in a day."

When Rome fell (476 A.D.) before the attacks of barbarous tribes her excellent postal system fell with her and many centuries passed before messages could again be regularly and quickly despatched between widely separated points. Charles the Great, the emperor of the Franks, established (800 A.D.) a postal system in his empire but the service did not long survive the great ruler. In the 13th century the merchants of the Hanse towns of Northern Germany could communicate with each other somewhat regularly by letter, but the ordinary people of these towns did not enjoy the privileges of a postal service. In the Middle Ages, as in the ancient times, the public post was established solely for the benefit of the government. Private messages had to be sent as best they could be by private messengers and at private expense. As late as the reign of Henry VIII (1509-1547) the only regular post route in England was one which was established for the exclusive use of the king.

But the time was soon to come when ordinary citizens as well as officers of state were to share in the benefits of a postal system. In 1635 Charles I of England gave orders that a post should run night and day between Edinburgh and London and that postmen should take with them all such letters as might be directed to towns on or near the road which connected the two cities. The rate of postage21 was fixed at two pence for a single letter when the distance was under sixty miles; four pence when the distance was between 60 and 140 miles; six pence for any longer distance in England; and eight pence from London to any place in Scotland. It was ordered that only messengers of the king should be allowed to carry letters for profit unless to places to which the king's post did not go. Here was the beginning of the modern postal system and the modern post-office. Henceforth the post was to carry not only the king's messages, but the messages of all people who would pay the required postage.

The example set by England in throwing the post open to the public was followed by other nations, and before a hundred years had passed nearly all the civilized countries of the world were enjoying the privilege and blessings of a well-organized postal system. It is true that the post for a long time moved very slowly – a hundred miles a day was regarded as a flying rate – and postage for a long time was very high, but the service grew constantly better and by the close of the nineteenth century trains were dashing along with the mails at the rate of a thousand miles a day and postage within a country had been reduced to two cents,22 while for a nickel a letter could be sent to the most distant parts of the globe.

Thus far we have traced the history of only one kind of message, the kind that has the form of a written document and that is conveyed by a human carrier over land and water from one place to another. But there is a kind of message which is not borne along by human hands and which does not travel on land or water. This is the telegraph,23 the message which darts through space and is delivered at a distant point almost at the very instant at which it is sent.

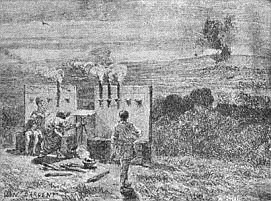

FIG. 5. – TELEGRAPHING BY MEANS OF FIRE, 150 B. C.

The first telegraph was an aerial message and consisted of a signal made by a flash of light. From the earliest times men have used fire signals as a means of sending messages to distant points. When the city of Troy in Asia Minor was captured by the Greeks (about 1100 B.C.) torches flashing their light from one mountain top to another quickly carried the news to the far-off cities of Greece. The ancient Greeks gave a great deal of attention to the art of signaling by fire and they invented several very ingenious systems of aerial telegraphy. The most interesting of these systems is one invented and described by the Greek historian Polybius, who flourished about 150 B.C. When signaling with fire Polybius arranged for using two groups of torches with five torches in each group, and for the purpose of understanding the signals he divided the letters of the alphabet into five groups of five letters each.24 The torches were raised according to a plan that made it possible to flash a signal that would indicate any letter of the alphabet that might be desired. Thus if the desired letter was the third one of the first group – that is, the letter k– one torch would show which group was meant and three torches would show which letter was meant (Fig. 5). In theory this system was perfect, for it provided for sending any kind of message whatever. But in practice it had little value, for it required so many torches and signals that an entire night was consumed in spelling out a few words.