полная версия

полная версияA Student's History of England, v. 2: 1509-1689

Samuel Rawson Gardiner

A Student's History of England, v. 2: 1509-1689 / From the Earliest Times to the Death of King Edward VII

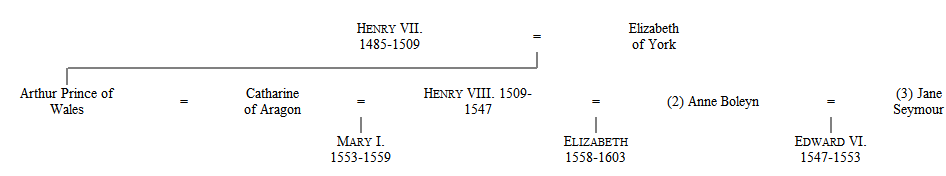

GENEALOGICAL TABLES

I

KINGS AND QUEENS OF ENGLAND (AFTER 1541 OF ENGLAND AND IRELAND) FROM HENRY VII. TO ELIZABETH

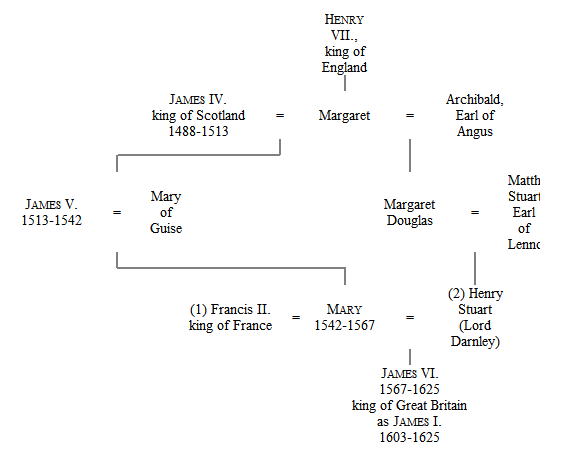

II

KINGS OF SCOTLAND AND GREAT BRITAIN, FROM JAMES IV. OF SCOTLAND TO WILLIAM AND MARY

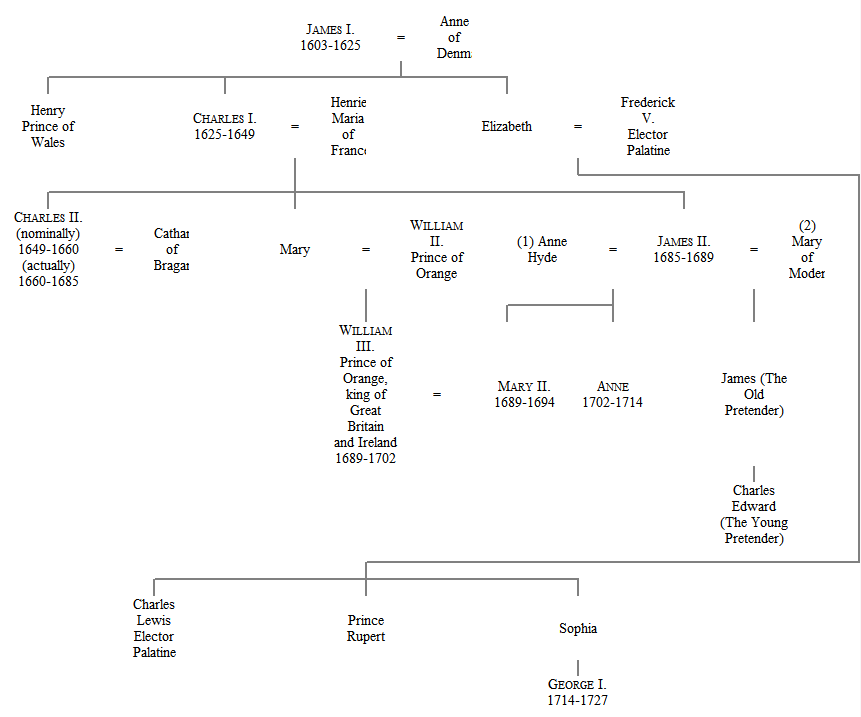

III

KINGS OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND FROM JAMES I. TO GEORGE I

IV

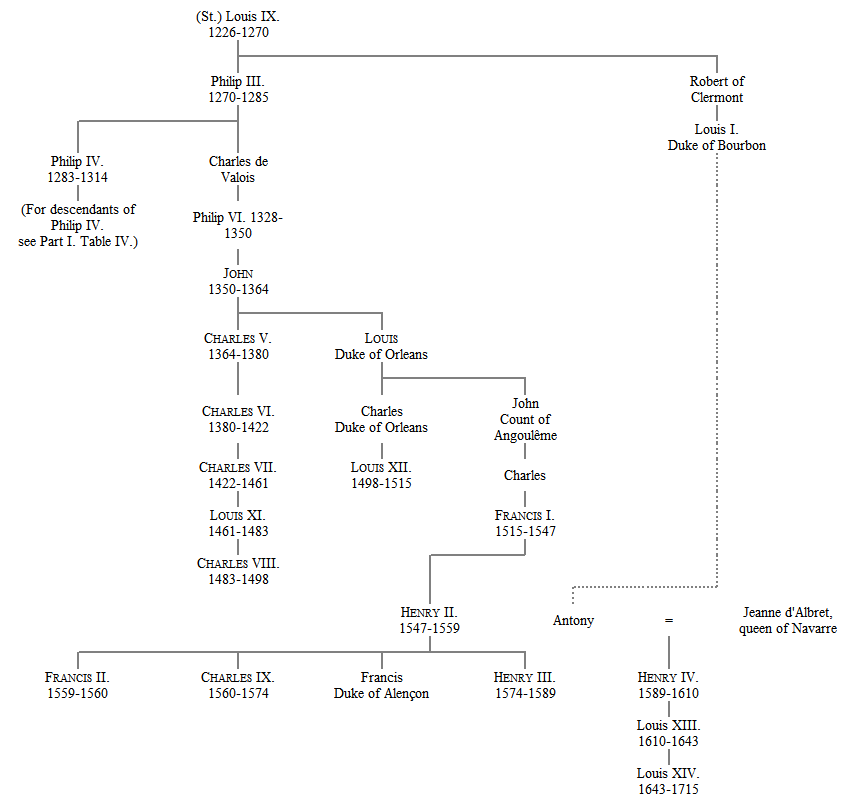

GENEALOGY OF THE KINGS OF FRANCE FROM LOUIS XII. TO LOUIS XIV., SHOWING THEIR DESCENT FROM LOUIS IX

V

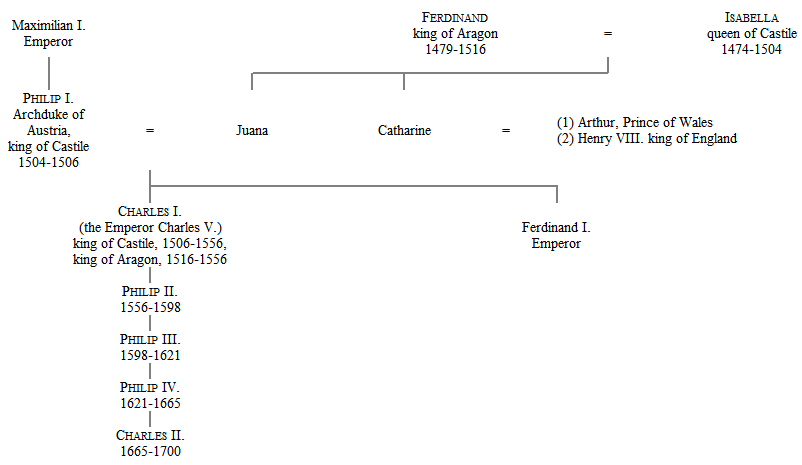

GENEALOGY OF THE KINGS OF SPAIN FROM FERDINAND AND ISABELLA TO CHARLES II

VI

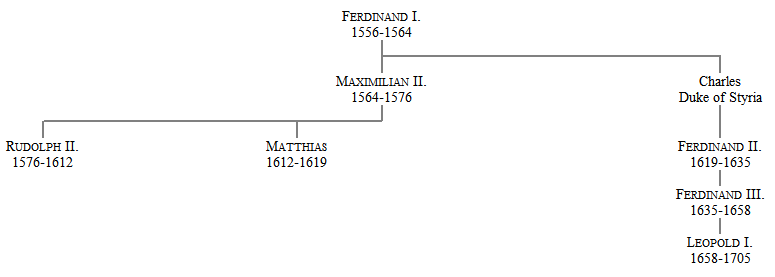

GENEALOGY OF THE GERMAN BRANCH OF THE HOUSE OF AUSTRIA FROM FERDINAND I. TO LEOPOLD I

(The dates given are those during which an archduke was emperor.)

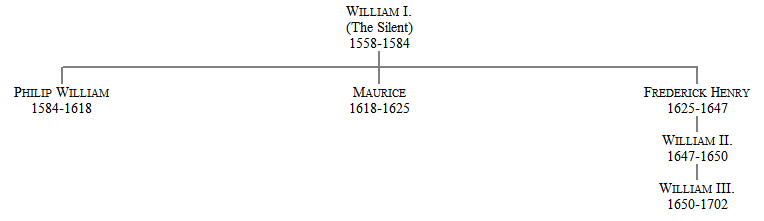

VII

GENEALOGY OF THE PRINCES OF ORANGE FROM WILLIAM I. TO WILLIAM III

PAGE

Genealogy of the Poles 399

" " children of Henry VIII. 411

" " Greys 421

" " last Valois kings of France 433

" " Guises 435

" of Mary and Darnley 438

" of the descendants of Charles I. 609

PART V

THE RENASCENCE AND THE REFORMATION 1509-1603

CHAPTER XXIV

HENRY VIII. AND WOLSEY. 1509-1527

LEADING DATESReign of Henry VIII., 1509-1547• Accession of Henry VIII. 1509

• Henry's first war with France 1512

• Peace with France 1514

• Charles V. elected Emperor 1519

• Henry's second French war 1522

• Francis I. taken captive at Pavia 1525

• The sack of Rome and the alliance between England and France 1527

1. The New King. 1509.– Henry VIII. inherited the handsome face, the winning presence, and the love of pleasure which distinguished his mother's father, Edward IV., as well as the strong will of his own father, Henry VII. He could ride better than his grooms, and shoot better than the archers of his guard. Yet, though he had a ready smile and a ready jest for everyone, he knew how to preserve his dignity. Though he seemed to live for amusement alone, and allowed others to toil at the business of administration, he took care to keep his ministers under control. He was no mean judge of character, and the saying which rooted itself amongst his subjects, that 'King Henry knew a man when he saw him,' points to one of the chief secrets of his success. He was well aware that the great nobles were his only possible rivals, and that his main support was to be found in the country gentry and the townsmen. Partly because of his youth, and partly because the result of the political struggle had already been determined when he came to the throne, he thought less than his father had done of the importance of possessing stored up wealth by which armies might be equipped and maintained, and more of securing that popularity which at least for the purposes of internal government, made armies unnecessary. The first act of the new reign was to send Empson and Dudley to the Tower, and it was significant of Henry's policy that they were tried and executed, not on a charge of having extorted money illegally from subjects, but on a trumped up charge of conspiracy against the king. It was for the king to see that offences were not committed against the people, but the people must be taught that the most serious crimes were those committed against the king. Henry's next act was to marry Catharine. Though he was but nineteen, whilst his bride was twenty-five, the marriage was for many years a happy one.

2. Continental Troubles. 1508-1511.– For some time Henry lived as though his only object in life was to squander his father's treasure in festivities. Before long, however, he bethought himself of aiming at distinction in war as well as in sport. Since Louis XII. had been king of France (see p. 354) there had been constant wars in Italy, where Louis was striving for the mastery with Ferdinand of Aragon. In 1508 the two rivals, Ferdinand and Louis, abandoning their hostility for a time, joined the Emperor Maximilian (see pp. 337, 348) and Pope Julius II. in the League of Cambrai, the object of which was to despoil the Republic of Venice. In 1511 Ferdinand allied himself with Julius II. and Venice in the Holy League, the object of which was to drive the French out of Italy. After a while the new league was joined by Maximilian, and every member of it was anxious that Henry should join it too.

3. The Rise of Wolsey. 1512.– England had nothing to gain by an attack on France, but Henry was young, and the English nation was, in a certain sense, also young. It was conscious of the strength brought to it by restored order, and was quite ready to use this strength in an attack on its neighbours. In the new court it was ignorantly thought that there was no reason why Henry VIII. should not take up that work of conquering France which had fallen to pieces in the feeble hands of Henry VI. To carry on his new policy Henry needed a new minister. The best of the old ones were Fox, the Bishop of Winchester, and Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, who, great nobleman as he was, had been contented to merge his greatness in the greatness of the king. The whole military organisation of the country, however, had to be created afresh, and neither Fox nor Surrey was equal to such a task. The work was assigned to Thomas Wolsey, the king's almoner, who, though not, as his enemies said, the son of a butcher, was of no exalted origin. Wolsey's genius for administration at once manifested itself. He was equally at home in sketching out a plan of campaign, in diplomatic contests with the wariest and most experienced statesmen, and in providing for the minutest details of military preparation.

4. The War with France. 1512-1513.– It was not Wolsey's fault that his first enterprise ended in failure. A force sent to attack France on the Spanish side failed, not because it was ill-equipped, but because the soldiers mutinied, and Ferdinand, who had promised to support it, abandoned it to its fate. In 1513 Henry himself landed at Calais, and, with the Emperor Maximilian serving under him, defeated the French at Guinegatte in an engagement known, from the rapidity of the flight of the French, as the Battle of the Spurs. Before the end of the autumn he had taken Terouenne and Tournai. War with France, as usual, led to a war with Scotland. James IV., during Henry's absence, invaded Northumberland, but his army was destroyed by the Earl of Surrey at Flodden, where he himself was slain.

5. Peace with France. 1514.– Henry soon found that his allies were thinking exclusively of their own interests. In 1512 the French were driven out of Italy, and Ferdinand made himself master of Navarre. In 1513 the warlike Pope, Julius II., died, and a fresh attempt of Louis to gain ground in Italy was decisively foiled. Henry's allies had got what they wanted, and in 1514 Henry discovered that to conquer France was beyond his power. Louis was ready to come to terms. He was now a widower. Old in constitution, though not in years, he was foolish enough to want a young wife. Henry was ready to gratify him with the hand of his younger sister Mary. The poor girl had fallen in love with Henry's favourite, Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, a man of sturdy limbs and weak brain, and pleaded hard against the marriage. Love counted for little in those days, and all that she could obtain from her brother was a promise that if she married this time to please him, she should marry next time to please herself. Louis soon relieved her by dying on January 1, 1515, after a few weeks of wedlock, and his widow took care, by marrying Suffolk before she left France, to make sure that her brother should keep his promise.

6. Wolsey's Policy of Peace. 1514-1518.– In 1514 the king made Wolsey Archbishop of York. In 1515 the Pope made him a Cardinal. Before the end of the year he was Henry's Chancellor. The whole of the business of the government passed through his hands. The magnificence of his state was extraordinary. To all observers he seemed to be more a king than the king himself. Behind him was Henry, trusting him with all his power, but self-willed and uncontrollable, quite ready to sacrifice his dearest friend to satisfy his least desire. As yet the only conflict in Henry's mind was the conflict about peace or war with France. Henry's love of display and renown had led him to wish to rival the exploits of Edward III. and Henry V. Wolsey preferred the old policy of Richard II. and Henry VI., but he knew that he could only make it palatable to the king and the nation by connecting the idea of peace with the idea of national greatness. He aspired to be the peacemaker of Europe, and to make England's interest in peace the law of the world. In 1515 the new king of France, Francis I., needed peace with England because he was in pursuit of glory in Italy, where he won a brilliant victory at Marignano. In 1516 Ferdinand's death gave Spain to his grandson, Charles, the son of Philip and Juana (see p. 358), and from that time Francis and Charles stood forth as the rivals for supremacy on the Continent. Wolsey tried his best to maintain a balance between the two, and it was owing to his ability that England, thinly populated and without a standing army, was eagerly courted by the rulers of states far more powerful than herself. In 1518 a league was struck between England and France, in which Pope Leo X., the Emperor Maximilian, and Charles, king of Spain, agreed to join, thus converting it into a league of universal peace. Yet Wolsey was no cosmopolitan philanthropist. He believed that England would be more influential in peace than she could be in war.

7. Wolsey and the Renascence.– In scheming for the elevation of his own country by peace instead of by conquest, Wolsey reflected the higher aspirations of his time. No sooner had internal order been secured, than the best men began to crave for some object to which they could devote themselves, larger and nobler than that of their own preservation. Wolsey gave them the contemplation of the political importance of England on the Continent. The noblest minds, however, would not be content with this, and an outburst of intellectual vigour told that the times of internal strife had passed away. This intellectual movement was not of native growth. The Renascence, or new birth of letters, sprung up in Italy in the fourteenth century, and received a further impulse through the taking of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453, when the dispersal of Greek teachers from the East revived the study of the Greek language. It was not merely because new teachers landed in Italy that the literature of the ancient world was studied with avidity. Men were weary of the mediæval system, and craved for other ideals than those of the devotees of the Church. Whilst they learnt to admire the works of the Greek and Latin authors as models of literary form, they caught something of the spirit of the ancient world. They ceased to look on man as living only for God and a future world, and regarded him as devoting himself to the service of his fellow-men, or even – in lower minds the temptation lay perilously near – as living for himself alone. Great artists and poets arose who gave expression to the new feeling of admiration for human action and human beauty, whilst the prevailing revolt against the religion of the middle ages gave rise to a spirit of criticism which refused belief to popular legends.

8. The Renascence in England.– The spirit of the Renascence was slow in reaching England. In the days of Richard II. Chaucer visited Italy, and Italian influence is to be traced in his Canterbury Tales. In the days of Henry VI. the selfish politician, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, purchased books, and gave to Oxford a collection which was the foundation of what was afterwards known as the Bodleian Library. Even in the Wars of the Roses the brutal John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester, and the gentle Earl Rivers, the brother of Elizabeth Woodville, were known as patrons of letters. The invention of printing brought literature within reach of those to whom it had hitherto been strange. Edward IV. patronised Caxton, the first English printer. In the peaceful reign of Henry VII. the seed thus sown sprang into a crop. There was, however, a great difference between the followers of the new learning in England and in Italy. In Italy, for the most part, scholars mocked at Christianity, or treated it with tacit contempt. In England there was no such breach with the religion of the past. Those who studied in England sought to permeate their old faith with the new thoughts.

9. The Oxford Reformers.– Especially was this the case with a group of Oxford Reformers, Grocyn, Linacre, and Colet, who were fighting hard to introduce the study of Greek into the University. Among these Colet specially addicted himself to the explanation of the epistles of St. Paul, insisting on following their plain meaning instead of the mystical interpretations then in vogue. In 1510 he founded St. Paul's School, that boys might be there taught without being subjected to the brutal flogging which was in those days the lot even of the most diligent of schoolboys. The most remarkable member of this group of scholars was Thomas More. Young More, who had hoped much from the accession of Henry VIII., had been disappointed to find him engaging in a war with France instead of cultivating the arts of peace. He meditated deeply over the miseries of his fellow-men, and longed for a time when governments would think it to be their highest duty to labour for those who are too weak to help themselves.

10. 'The Utopia.' 1515-1516.– In 1515 and 1516 More produced a book which he called Utopia, or Nowhere, intending it to serve as a satire on the defects of the government of England, by praising the results of a very different government in his imaginary country. The Utopians, he declared, fought against invaders of their own land or the land of their allies, or to deliver other peoples from tyranny, but they made no wars of aggression. In peace no one was allowed either to be idle or overworked. Everyone must work six hours a day, and then he might listen to lectures for the improvement of his mind. As for the religion of Utopia, no one was to be persecuted for his religious opinions, as long as he treated respectfully those who differed from him. If, however, he used scornful and angry words towards them, he was to be banished, not as a despiser of the established religion, but as a stirrer up of dissension. Men of all varieties of opinion met together in a common temple, the worship in which was so arranged that all could take part in it. Amongst their priests were women as well as men. More practical was the author's attack on the special abuses of the times. England swarmed with vagrants, who easily passed into robbers, or even murderers. The author of Utopia traced the evil to its roots. Soldiers, he said, were discharged on their return home, and, being used to roving and dissolute habits, naturally took to vagrancy. Robbery was their only resource, and the law tempted a robber to murder. Hanging was the penalty both for robbing and murder, and the robber, therefore, knowing that he would be hanged if he were detected, usually killed the victim whom he had plundered in order to silence evidence against himself; and More consequently argued that the best way of checking murder would be to abolish the penalty of death for robbery. Another great complaint of More's was against the ever-growing increase of inclosures for pasturage. "Sheep," he said, "be become so great devourers and so wild that they eat up and swallow down the very men themselves. They consume, destroy, and devour whole fields, houses, and cities." More saw the evil, but he did not see that the best remedy lay in the establishment of manufactures, to give employment in towns to those who lost it in the country. He wished to enforce by law the reversion of all the new pasturage into arable land.

11. More and Henry VIII.– Henry VIII. was intolerant of those who resisted his will, but he was strangely tolerant of those who privately contradicted his opinions. He took pleasure in the society of intelligent and witty men, and he urged More to take office under him. More refused for a long time, but in 1518– the year of the league of universal peace – believing that Henry was now a convert to his ideas, he consented, and became Sir Thomas More and a Privy Councillor. Henry was so pleased with his conversation that he tried to keep him always with him, and it was only by occasionally pretending to be dull that More obtained leave to visit his home.

12. The Contest for the Empire. 1519.– In January 1519 the Emperor Maximilian died. His grandson Charles was now possessed of more extensive lands than any other European sovereign. He ruled in Spain, in Austria, in Naples and Sicily, in the Netherlands, and in the County of Burgundy, usually known as Franche Comté. Between him and Francis I. a struggle was inevitable. The chances were apparently, on the whole, on the side of Charles. His dominions, indeed, were scattered, and devoid of the strength given by national feeling, whilst the smaller dominions of Francis were compact and united by a strong national bond. In character, however, Charles had the superiority. He was cool and wary, whilst Francis was impetuous and uncalculating. Both sovereigns were now candidates for the Empire. The seven electors who had it in their gift were open to bribery. Charles bribed highest, and being chosen became the Emperor Charles V.

13. The Field of the Cloth of Gold. 1520.– Wolsey tried hard to keep the peace. In 1520 Henry met Francis on the border of the territory of Calais, and the magnificence of the display on both sides gave to the scene the name of the Field of the Cloth of Gold. In the same year Henry had interviews with Charles. Peace was for a time maintained, because both Charles and Francis were still too much occupied at home to quarrel, but it could hardly be maintained long.

The embarkation of Henry VIII. from Dover, 1520: from the original painting at Hampton Court.

14. The Execution of the Duke of Buckingham. 1521.– Henry was entirely master in England. In 1521 the Duke of Buckingham, son of the Buckingham who had been beheaded by Richard III., was tried and executed as a traitor. His fault was that he had great wealth, and that, being descended from the Duke of Gloucester, the youngest son of Edward III., he had not only cherished some idea of claiming the throne after Henry's death, but had chattered about his prospects. In former days justice was not to be had by those who offended the great lords. Now, one despot had stepped into the place of many, and justice was not to be had by those who offended the king. The legal forms of trial were now as before observed. Buckingham was indeed tried before the court of the Lord High Steward, which consisted of a select number of peers, and which had jurisdiction over peers when Parliament was not sitting. These, however, were no more than forms. It was probably a mingled feeling of gratitude and fear which made peers as well as ordinary juries ready to take Henry's word for the guilt of any offender.

15. Another French War. 1522-1523.– The diplomacy of those days was a mere tissue of trickery and lies. Behind the falsehood, however, Wolsey had a purpose of his own, the maintenance of peace on the Continent. Yet, in 1521 war broke out between Charles and Francis, both of whom laid claim to the Duchy of Milan, and it was evident that Wolsey would be unable to keep England out of the struggle. If there was to be fighting Henry preferred to fight France rather than to fight Charles. In 1522, in conjunction with Charles, he invaded France. There was burning and ravaging enough, but nothing of importance was done. Nevertheless in 1523 Henry was in high spirits. A great French noble, the Duke of Bourbon, provoked by ill-treatment, revolted against Francis, and Henry and Charles fancied that he would open a way to them into the heart of France. If Henry was to be crowned at Paris, which was the object on which he was bent, he must have a supply of money from his subjects. Though no Parliament had been summoned for nearly eight years, one was summoned now, of which More was the Speaker. Wolsey asked for an enormous grant of 800,000l., nearly equal to 12,000,000l. at the present day. Finding that the Commons hesitated, he swept into the House in state to argue with them. Expecting a reply, and finding silence, he turned to More, who told him that it was against the privilege of the House to call on it for an immediate answer. He had to depart unsatisfied, and after some days the House granted a considerable sum, but far less than that which had been demanded. Wolsey was now in a position of danger. His own policy was pacific, but his master's policy was warlike, and he had been obliged to make himself the unquestioning mouthpiece of his master in demanding supplies for war. He had long been hated by the nobles for thrusting them aside. He was now beginning to be hated by the people as the supposed author of an expensive war, which he would have done his best to prevent. He had not even the advantage of seeing his master win laurels in the field. The national spirit of France was roused, and the combined attack of Henry and Charles proved as great a failure in 1523 as in 1522. The year 1524 was spent by Wolsey in diplomatic intrigue.

16. The Amicable Loan. 1525.– Early in 1525 Europe was startled by the news that Francis had been signally defeated by the Imperialists at Pavia, and had been carried prisoner to Spain. Wolsey knew that Charles's influence was now likely to predominate in Europe, and that unless England was to be overshadowed by it, Henry's alliance must be transferred to Francis. Henry, however, saw in the imprisonment of Francis only a fine opportunity for conquering France. Wolsey had again to carry out his master's wishes as though they were his own. Raking up old precedents, he suggested that the people should be asked for what was called an Amicable Loan, on the plea that Henry was about to invade France in person. He obtained the consent of the citizens of London by telling them that, if they did not pay, it might 'fortune to cost some their heads.' All over England Wolsey was cursed as the originator of the loan. There were even signs that a rebellion was imminent. In Norfolk when the Duke of Norfolk demanded payment there was a general resistance. On his demanding the name of the captain of the multitude which refused to pay, a man told him that their captain's 'name was Poverty,' and 'he and his cousin Necessity' had brought them to this. Wolsey, seeing that it was impossible to collect the money, took all the unpopularity of advising the loan upon himself. 'Because,' he wrote, 'every man layeth the burden from him, I am content to take it on me, and to endure the fame and noise of the people, for my goodwill towards the king … but the eternal God knoweth all.' Henry had no such nobility of character as to refuse to accept the sacrifice. He liked to make his ministers scapegoats, to heap on their heads the indignation of the people that he might himself retain his popularity. For three centuries and a half it was fully believed that the Amicable Loan had originated with Wolsey.