полная версия

полная версияThe Story of the Atlantic Telegraph

Thus, after three anxious hours, the danger was past, and the next morning the report of the ship is, "A fresh breeze from the southward, a dull gray sky, with occasional rain, and a moderate sea."

"Thursday. – There was a fresh breeze in the afternoon yesterday, increasing toward evening. It brought a heavy swell on the port quarter, which caused the ship to roll. The paying out from the after tank went on steadily. Two of the large buoys were lifted by derrick from the deck near the bows of the ship, and placed in position on the port and starboard side of the forward pick-up machinery, ready for letting go if necessary. The sun went down with an angry look, and the scud came rapidly from the eastward, the sea rising. A wind dead aft is not the best for cable laying, particularly if any accident should take place. By half-past eleven to-night we shall have exhausted the contents of the after tank, and the cable will then be paid out from the fore tank along the trough to the stern, the distance from the centre of the tank to the paying-out machinery being four hundred and ninety-four feet. Last night the swell was very heavy, to which the Great Eastern proved herself not insensible. Her rolling, like everything else appertaining to her, is done on a grand scale. We see the liveliness with which that operation is performed on board the Albany and Medway, and we are not at all disposed to be too critical in our observations on our own movements. The speed of the ship was kept at four and a half during the night – the slower the better, is the opinion of all on board —festina lente. We are consuming about one hundred tons a day of the seven thousand tons of coal which we had on board when we left Berehaven, and Mr. Beckwith, who has been engineer of the Great Eastern from her first voyage to the present moment, says her engines were never in better order; and their appearance and working do him and his able staff of assistant engineers the greatest credit.

"Friday. – Yesterday was a day of complete success, the paying out in every respect satisfactory. The wind still from the eastward, but inclined to draw to the northward, the sea entirely gone down. As Mr. Canning told us we should see the after tank emptied at eleven o'clock, ship's time, we were all collected there about ten o'clock, by which time the cable was down to the last flake. Next to having daylight for changing from the after to the fore tank, we could not have had a more favorable time – clear starlight, no wind, and a smooth sea. Looking down into the tank, the scene was highly picturesque. The cable-watch, whose figures were lighted up by the lamps suspended from above, slowly and cautiously lifted the turns of the coil to ease their path to the eye. As each found its way to the drum, the wooden floor of the tank showed itself, and then we saw more floor, and as its area increased the cable swept along its surface with a low, subdued noise, until, with a graceful curve, it mounted to the outlet, where it was soon to join a fresh supply; and now we hear the word passed that they have arrived at the last turn, and the men who stood on the stages of the platform of the eye with the bight, watch the arrival of the cable and pass it up with tender caution, until it reaches the summit; then it rushes down a wooden incline to meet the spliced rope, which had by this time come down along the trough leading from the forward tank. This operation was conducted with great skill by Mr. Canning and his experienced assistants, Messrs. Clifford and Temple. At eleven minutes past one a. m. (Greenwich time), the fresh rope was going over the stern, and the screw engines going ahead at thirteen minutes past one. A watch of four men is now stationed, fore and aft, all along the trough, which is illuminated by many lamps at short distances from each other. A lamp with a green light indicates the mile-mark as it comes up from the tank, and this signal is repeated until it reaches the stern, where it is recorded by the clerk who keeps the cable-log, in an office adjoining the paying-out machinery. A red lamp indicates danger. During the daytime red and blue flags are used. All through the night the sea was smooth as glass, and by this morning we saw that a sensible impression had been made on the contents of the fore tank. The ship begins to lighten at the bows, and by this time to-morrow will come up more as the cable passes out of the tank.

"Saturday. – Yesterday was our seventh day of paying out cable, and so far we have been more fortunate than the expedition of last year. During the same period of 1865, two faults had occurred – one on the twenty-fourth July, the other on the twenty-ninth – causing a detention of fifty-six hours. At three p. m. we were half-way, and passed where the Atlantic Cable of 1858 parted twice, on the twenty-sixth and twenty-eighth of June – sad memories to many! We feel, however, that every hour is increasing our chance of effecting this great work. 'I believe we shall do it this time, Jack,' I heard one of our crew say to another last night. 'I believe so too, Bill,' was the reply; 'and if we don't, we deserve to do it, and that's all.' It blew very hard from two o'clock yesterday, up to 10 p. m., by which time the wind gradually found its way from south-west to north-west, which is right ahead, just what we want for cable-laying. The Terrible and the two other ships plunged into the very heavy sea which the southwester raised, and we made up our minds, from what we saw, that the Great Eastern is the right ship to be in, in a gale of wind. During the night heavy showers of rain. This morning the sea was comparatively smooth, and the sky showed welcome patches of bright blue. If all goes well, we shall be up to-morrow evening at the place where last year's cable parted. A couple of days would bring us to shallower water, and then we may fairly look out for our 'Heart's Content.' Messages come from England, with the news, regularly and speedily – excellent practice for the clerks on shore and on board ship – great comfort to us, and the best evidence to those who will read this journal, of the great fact that, up to this time, the cable is doing its electric work efficiently."

The interest of the voyage was greatly increased by the news daily received from Europe. Though in the middle of the Atlantic, they were still joined with the Old World, and messages came to the "Great Eastern Telegraph" as regularly as to the Times in London; reporting the quotations of the Stock Exchange, the debates in Parliament, and all the news of home. But what was far more exciting, was the tidings of the great events transpiring on the Continent. While the expedition had been preparing in England, a war had broken out of tremendous magnitude. Austria, Prussia, and Italy had rushed into the field. Armies, such as had not met since the fatal day of Leipsic, stood in battle array, and the thunder of war was echoing and reëchoing among the mountains of Bohemia. Amid these convulsions the fleet set sail; but it was still linked with the nations which it left behind, and received tidings from day to day. What great events were thus heralded to them in mid-ocean may be seen by a few items gleaned from the numerous despatches:

"Saturday evening, July 14th. – General Cialdini is moving upon Rovigo with an army of one hundred thousand men and two hundred guns. The Austrians have evacuated the whole country between the Mincio and Adige."

A day or two later:

"Cialdini has occupied Padua, twenty-three miles from Venice, on the railway connecting that city with the Quadrilateral, and the Austrians are shut up in Venice."

"Tuesday, 17th. – Prussians had successful engagement before Olmütz yesterday; captured six guns. Further fighting expected to-day. Austrians withdrawing from Moldavia toward Vienna." – "Conflict between Prussians and Federals. Prussians completely victorious. Federals evacuating Frankfort, and Prussians marching there."

"Thursday, 19th. – Prussians repeating victories, and gaining adhesions from small States. The main army within fifty miles of Vienna – have cut the railway to Vienna. Austrian army between Prussians and Vienna, under Archduke, one hundred and sixty thousand men. Money and archives removed from Vienna to Comorn."

"20th. – Frankfort occupied by the Prussians, who are marching on Vienna. Yesterday, Italian fleet, consisting of iron-clad vessels and several steamers, opened attack on Island of Lissa on the coast of Dalmatia – result not known."

The next day it is reported thus:

"Severe naval engagement off Lissa. Austrians claim the victory. Sunk one Italian iron-clad, run down another, blew up a third."

"July 21st. – Prussians crossed river; march near Holitzon, Hungary. Austria accepted proposal of armistice. Prussia will abstain from hostilities for five days, during which Austria will have to notify acceptance of preliminaries. A long letter published from the King of Prussia to the Queen, giving account of battle of Königgrätz."

The interest excited by such news may be imagined, coming while the events were yet fresh. Twice a day was the bulletin set up on the deck, and was surrounded by an eager crowd reading what had transpired on the Continent but a few hours before. Nor was the intelligence confined to the Great Eastern. By an arrangement of signals, more complete than ever was used in a squadron before, the news was telegraphed to the convoy. All the ships had been furnished with experienced signal-men by the Admiralty. The system adopted was that known as Colomb's Flash Signals, by which, even in the darkest night, messages could easily be flashed to a distance of several miles. Thus all the ships were supplied with news twice a day, and the great military events in Europe were discussed in every cabin as eagerly as in the clubs of London. Again Deane's Diary reports:

"Sunday, July 22d. – Still success to record. A bright clear day, with a fresh and invigorating breeze from the north-west. Cable going out with unerring smoothness, at the rate of six miles an hour. There has been great improvement in the insulation. This remarkable improvement is attributable to the greatly decreased temperature of, and pressure on, the cable in the sea. This is a very satisfactory result to Mr. Willoughby Smith. Signals, too, come every hour more distinctly. This morning the breeze freshened. We are now about thirty miles to the southward of the place where the cable parted on the second of August, 1865, having then paid out one thousand two hundred and thirteen miles. Captain Anderson read divine service in the dining saloon.

"Monday. – Between six and seven p. m. yesterday, we passed over the deepest part of our course. There was no additional strain on the dynamometer, which indicated from ten to fourteen hundred, the cable going out with its accustomed regularity. The wind still fresh from the north-west. During the night it went round to the southwest, and this morning there is a long roll from the southward.

"At forty-six minutes past eleven a. m., Mr. Cyrus Field sent a message to Valentia, requesting Mr. Glass to obtain the latest news from Egypt, India, and China, and other distant countries, so that on our arrival at Heart's Content we shall be able to transmit it to the principal cities of the United States. In just eight minutes he had a reply in these words: 'Your message received, and is in London by this.' Outside the telegraph room there is a placard put up, on which is posted the news shortly after its arrival, and groups of the crew may be seen reading it, just as we see a crowd at a newspaper office in London. Mr. Dudley, the artist, has made a very spirited sketch of 'Jack' reading the morning news, for he is supplied with the latest intelligence from the seat of war twice a day!26 How he will grumble when he gets ashore! He is not going to pay a pound a word for news, but his newspapers will supply it to him, and he does not know or care what it costs. But what a sum has been spent in Atlantic telegraphs! It cannot now fall short of two millions and a half of pounds, or over twelve millions of dollars. More millions will be found if it shall be practically proved that America can permanently talk to England, and through her to the eastern hemisphere, and England to America by this ocean wire. At a quarter to twelve to-day but two hundred and fifteen miles of cable remained to be paid out of the fore tank. To-morrow night we hope to see it empty – then, for a small supply from the main tank, and then – but, hopeful though we are, let us not anticipate.

"Tuesday. – Breakfast at eight. Lunch at one. Dinner at six. Tea at eight. Five hundred and two souls who live on board this huge ship following their prescribed occupations. Cable going out merrily. Electrical tests and signals perfect, and this is the history of what has taken place from noon yesterday to noon to-day. May we have three days more of such delightful monotony! It rained very hard during yesterday evening, and as we approach the Banks of Newfoundland we get thick and hazy weather."

The latter part of the voyage did not fulfil in all respects the promise of the first. The bright skies were gone; and instead perpetual fog hung over the water, while often the clouds poured down their floods. Thus the diary continues:

"Wednesday. – Fog and thick rain – just the weather to expect on approaching the Banks of Newfoundland. The convoy keep their position, and though sometimes the fog hides the ships from our view, yet we know where they are by their signal-whistles – two from the Terrible, three from the Medway, and four from the Albany, which are replied to by the prolonged single shriek from our whistle. At fifty-two minutes past one, Greenwich time (ship's time, forty-five minutes past ten p. m., last night), the fore tank being nearly empty, preparations were made for passing the bight of the cable into the main tank. At fifteen minutes past two all the jockey-wheels of the paying-out machinery were up, and the brakes released. Twenty-three minutes past two the bight was passed steadily and cautiously by the cable hands outside of the trough to the main tank, and at thirty-five minutes past two the splice went over the stern in 1542.8 fathoms. By arrangement with Sir James Hope, the admiral of the North-American station, who has received instructions from the Admiralty to give the present expedition every assistance in his power, a frigate or sloop will be placed in longitude 48°, 25', 52", which is just thirty miles from the entrance of Trinity Bay, and sixty from Heart's Content. She will probably hang on by a kedge in that position, which shows the 'fair way' right up the bay; and if it be clear, we ought to see her about daybreak on Friday morning. The fog was very thick this morning, but occasionally lifts; as long as the wind is from south-west we cannot expect clear weather."

As the week drew on, it was evident that they were approaching the end of their voyage. By Thursday they had passed the great depths of the Atlantic, and were off soundings. Besides their daily observations, there were many signs, well known to mariners, that they were near the coast. There were the sea-birds, and they could almost snuff the smell of the land, such as once greeted the sharp senses of Columbus, and made him sure that he was floating to some undiscovered shore. Captain Anderson had timed his departure so that he should approach the American coast at the full moon; but for the last two or three nights, as the round orb rose behind them, banks of cloud hung so heavily upon the water, that the moonlight only gleamed faintly through the vaporous air, and the fleet seemed like the phantom ships of the Ancient Mariner, drifting on through fog and mist.

"Thursday. – All day yesterday it was as 'thick as mustard.' We have had now forty-eight hours of fog. Though it lifted a little this morning, at five a. m., it still looks like more of it. Captain Anderson signalled to the Albany, at fifteen minutes past ten last night, to start at daybreak, and proceed to discover the station ship, and report us at hand. Should she fail to find her, then to try and make the land and guide us up Trinity Bay. Another signal was sent at half-past twelve to the effect that the Terrible and Medway would be sent ahead to meet the Albany and establish a line to lead us in even with a fog. The Albany started at half-past three. At forty-five minutes past four, Greenwich time, the cable engineer in charge took one weight off each brake of the paying-out machinery. At forty minutes past seven all weights taken off, the assumed depth being three hundred fathoms. The indicated strain on the dynamometer gradually decreasing. Speed of ship five knots. We are going to try and pick up the cable of 1865 in two thousand five hundred fathoms (and we mean to succeed too); therefore should the cable we are now paying out part, it can be understood how easy it would be to raise it from a depth of three hundred fathoms. At fifty-five minutes past eight we signalled to the Terrible to sound, and received a reply, one hundred and sixty fathoms. At half-past eleven we informed her that when at the buoy off Heart's Content she should have her paddle-box boat and two cutters ready to be alongside immediately, for holding the bight of the cable during the splice and laying the shore end. The Medway was told at the same time to prepare two five-inch ropes, and two large mushroom anchors, with fifty fathoms of chain, for anchoring during the splice in one hundred and seventy fathoms of water, and we intimated to her that when inside of Trinity Bay we should signal for two boats to take hands on board her for shore end. News of to-day, telegram from Mr. Glass in reply to one from Mr. Canning: I congratulate you all most sincerely on your arrival in one hundred and thirty fathoms. I hope nothing will interfere to mar the hitherto brilliant success, and that the cable will be landed to-morrow.'"

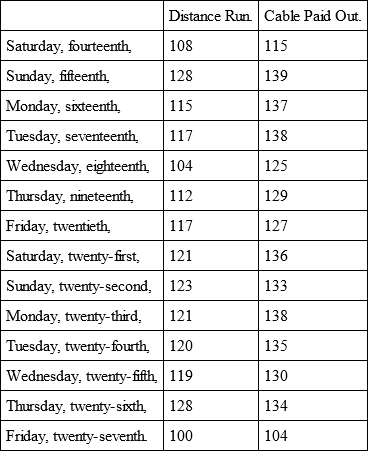

As the voyage is about to end, we give the distances run from day to day, which show a remarkable uniformity of progress:

From this it appears that the speed of the ship was exactly according to the running time fixed before she left England. On the last voyage it was thought that she had once or twice run too fast, and thus exposed the cable to danger. It was, therefore, decided to go slowly but surely. Holding her back to this moderate pace, her average speed, from the time the splice was made till they saw land, was a little less than five nautical miles an hour, while the cable was paid out at an average of not quite five and a half miles. Thus the total slack was about eleven per cent, showing that the cable was laid almost in a straight line, allowing for the swells and hollows in the bottom of the sea.

"Friday, July 27th. – Shortly after two p. m., yesterday, two ships, which were soon made out to be steamers, were seen to the westward; and the Terrible, steaming on ahead, in about an hour signalled to us that H.M.S. Niger was one of them, accompanied by the Albany. The Niger, Captain Bruce, sent a boat to the Terrible as soon as he came up with her. The Albany shortly afterward took up her position on our starboard quarter, and signalled that she spoke the Niger at noon, bearing E. by N., and that the Lily was anchored at the station in the entrance of Trinity Bay, as arranged with the Admiral. The Albany also reported that she had passed an iceberg about sixty feet high. At twenty minutes after four p. m., the Niger came on our port side, quite close, and Captain Bruce, sending the crew to the rigging and manning the yards, gave us three cheers, which were heartily returned by the Great Eastern. She then steamed ahead toward Trinity Bay. The Albany was signalled to go on immediately to Heart's Content, clear the northeast side of the harbor of shipping, and place a boat with a red flag for Captain Anderson to steer to, for anchorage. Just before dinner we saw on the southern horizon, distant about ten miles, an iceberg, probably the one which the Albany met with. It was apparently about fifty or sixty feet in height. The fog came on very thick about eight p. m., and between that and ten we were constantly exchanging guns and burning blue lights with the Terrible, which, with the Niger, went in search of the Lily, station ship. The Terrible being signalled to come up and take her position, informed us they had made the Lily out, and that she bore then about E.N.E. distant four miles. Later in the night Captain Commerill said that if Captain Anderson would stop the Great Eastern, he would send the surveyor Mr. Robinson, R. N., who came out in the Niger, on board of us, and about three the engines were slowed, and the Terrible shortly afterwards came alongside with that officer. Catalina light, at the entrance of Trinity Bay, had been made out three hours before this, and the loom of the coast had also been seen. Fog still prevailing! According to Mr. Robinson's account, if they got one clear day in seven at the entrance of Trinity Bay, they considered themselves fortunate. Here we are now (six a. m.), within ten miles of Heart's Content, and we can scarcely see more than a ship's length. The Niger, however, is ahead, and her repeated guns tell us where we are with accuracy. Good fortune follows us, and scarcely has eight o'clock arrived when the massive curtain of fog raises itself gradually from both shores of Trinity Bay, disclosing to us the entrance of Heart's Content, the Albany making for the harbor, the Margaretta Stevenson, surveying vessel, steaming out to meet us, the preärranged pathway all marked with buoys by Mr. J. H. Kerr, R. N., and a whole fleet of fishing boats fishing at the entrance.

"We could now plainly see that Heart's Content, so far as its capabilities permitted, was prepared to welcome us. The British and American flags floated from the church and telegraph station and other buildings. We had dressed ship, fired a salute, and given three cheers, and Captain Commerill of H.M.S. Terrible was soon on board to congratulate us on our success. At nine o'clock, ship's time, just as we had cut the cable and made arrangements for the Medway to lay the shore end, a message arrived giving us the concluding words of a leader in this morning's Times: 'It is a great work, a glory to our age and nation, and the men who have achieved it deserve to be honored among the benefactors of their race.' – 'Treaty of peace signed between Prussia and Austria!' It was now time for the chief engineer, Mr. Canning, to make the necessary preparations for splicing on board the Medway. Accompanied by Mr. Gooch, M.P., Mr. Clifford, Mr. Willoughby Smith, and Messrs. Temple and Deane, he went on board, the Terrible and Niger having sent their paddle-box boats and cutters to assist. Shortly afterward the Great Eastern steamed into the harbor and anchored on the north-east side, and was quickly surrounded by boats laden with visitors. Mr. Cyrus Field had come on shore before the Great Eastern had left the offing, with a view of telegraphing to St. John's to hire a vessel to repair the cable unhappily broken between Cape Ray, in Newfoundland, and Cape North, in Breton Island. Before a couple of hours the shore end will be landed, and it is impossible to conceive a finer day for effecting this our final operation. Even here, people can scarcely realize the fact that the Atlantic Telegraph Cable has been laid. To-morrow, however, Heart's Content27 will awaken to the fact that it is a highly favored place in the world's esteem, the western landing-place of that marvel of electric communication with the Eastern hemisphere, which is now happily, and we hope finally, established."

This simple record, so modestly termed the Diary of the Expedition, tells the story of this memorable voyage in a way that needs no embellishment. But if from the ship's deck we transfer ourselves to the shore, we may get a new impression of the closing scene. We can well believe the sensation of wonder and almost of awe, on the morning when the ships entered that little harbor of Newfoundland. In England the progress of the expedition was known from day to day, but on this side of the ocean all was uncertainty. Some had gone to Heart's Content, hoping to witness the arrival of the fleet, but not so many as the year before, for the memory of the last failure was too fresh, and they feared another disappointment. But still a faithful few were there, who kept their daily watch. The correspondents of the American papers report only a long and anxious suspense, till the morning when the first ship was seen in the offing. As they looked toward her, she came nearer – and see, there is another and another! And now the hull of the Great Eastern loomed up all glorious in the morning sky. They were coming! Instantly all was wild excitement on shore. Boats put off to row toward the fleet. The Albany was the first to round the point and enter the bay. The Terrible was close behind. The Medway stopped an hour or two to join on the heavy shore end, while the Great Eastern, gliding calmly in as if she had done nothing remarkable, dropped her anchor in front of the telegraph house, having trailed behind her a chain of two thousand miles, to bind the Old World to the New.